Vince Molyneaux

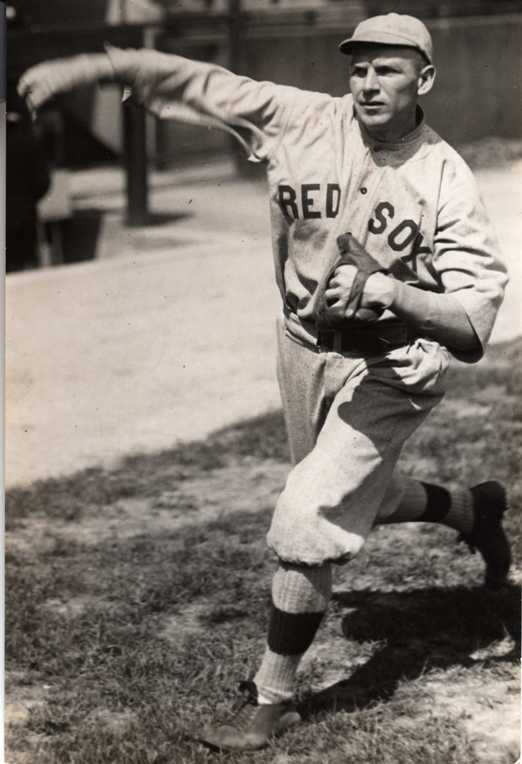

He never had a hit, never made an error, and pitched only 32 2/3 innings in 13 major league games, but he was a member of the World Champion 1918 Red Sox. Standard reference books show Vincent Leo Molyneaux as born near Niagara Falls, in Lewiston, New York, on August 17, 1888, although August 17, 1890 was the date he provided when he registered for the military draft during the First World War. A 6’0" 180-pound right-hander, Molyneaux was signed out of college and brought to the major leagues at the somewhat advanced age of 28 (or perhaps 26). The 1890 birth date seems more reliable. It confirms information his parents provided during the United States Census of 1900, which indicated Vincent was nine years old at the time, born in August 1890.

He never had a hit, never made an error, and pitched only 32 2/3 innings in 13 major league games, but he was a member of the World Champion 1918 Red Sox. Standard reference books show Vincent Leo Molyneaux as born near Niagara Falls, in Lewiston, New York, on August 17, 1888, although August 17, 1890 was the date he provided when he registered for the military draft during the First World War. A 6’0" 180-pound right-hander, Molyneaux was signed out of college and brought to the major leagues at the somewhat advanced age of 28 (or perhaps 26). The 1890 birth date seems more reliable. It confirms information his parents provided during the United States Census of 1900, which indicated Vincent was nine years old at the time, born in August 1890.

Vincent was the older child of parents who each traveled some distance to settle near Niagara Falls – Joseph Molyneaux, a laborer from Louisiana born in February 1863, and Kathryn "Kate" Dempsey, who was born in Ireland in August 1869. The couple also had a daughter, Christina, born in January 1897. Joseph Molyneaux was listed as a Louisiana native in the 1900 census, but as born in New York in the 1880 census, at which time he was working as a book binder. The 1890 census records were lost to fire, but the 1910 census shows Vincent and Christina still living at home in Niagara Falls, and Maggie Dempsey, Kate’s sister, working as a stitcher in a book factory at age 25 and also living in the house on Garden Avenue. Vincent was working at the time as a laborer in the food industry. Joseph Molyneaux was a cooper working for the railroad. (Oddly, none of them appear in the 1920 census, yet in 1930 Kathryn Molyneaux and Margaret Dempsey were both still living at Garden Avenue. Vincent shows up nowhere in the country in either 1920 or 1930.) There were other Molyneaux in the area, and even today there is a section of Lewiston known as Molyneaux Corners.

As a student at Niagara Falls High School, Vincent played with the Carter Crume company ball team. Carter Crume Co. Ltd. was a manufacturer of sales books, perhaps where his father and aunt Maggie worked. As an ace pitcher for the Crumes, Vince caught the eye of major league scouts, several of whom attended a seven-game series. "Squinch" Molyneaux was the starting pitcher in the first game of the series, and pitched a no-hitter.

In late May 1914, Molyneaux was acquired by the Jamestown (New York) Giants of the Interstate League. He debuted with a 7-1 complete game win over the Wellsville (New York) Rainmakers. The Jamestown Evening Journal wrote that he "showed up in great style. He has everything required by a successful pitcher in the flinging line with a beautiful change of pace thrown in, and in addition fields his position in fine style." He had a tendency to walk a lot of batters, but did very well, running up his record to 9-2 by July 11. He suffered three consecutive losses from July 15 to 19, the latter two by scores of 4-3 and 3-2, and then disappeared from the box scores for three weeks having been injured in a "street car smashup." Coming back, "Molly" generally pitched quite well but saw his record deteriorate. Jamestown was no-hit by Wellsville in one of his starts; the Warren (Pennsylvania) Bingoes beat them 2-1 in another, and the Bradford (Pennsylvania) Drillers shut them out, 2-0. Then he lost a 1-0 game to the Hornell (New York) Green Sox despite throwing an excellent five-hitter with eight strikeouts and no walks. By year’s end, he had a record of 11-12, earning the final win on September 12 by throwing six innings of relief while going 2-for-3 at the plate and driving in the final three runs in the 6-5 win over Wellsville.

Jamestown played Bradford in a post-season series for the Interstate League pennant, and Molyneaux came on in relief in Game Four after Jamestown was down 5-1. He pitched five innings of scoreless ball but in the top of the ninth "Molyneaux somehow or other forgot that Zurfluh was perched on third base and during one of his mighty windups, Zurfluh stole home, reaching the plate before the ball had been delivered." Mention of Molyneaux’s elaborate windup would turn up again.

Molyneaux started Game Five and threw three scoreless innings, but then allowed two runs in the fourth and another in the fifth. Molyneaux, never much of a hitter despite the one standout game, was 0-for-5 at the plate. Jamestown lost the game, 4-2, but won the series in seven games.

After the season, Jamestown included him on its reserve list – as they did with a man named William Molyneaux. This presents a bit of a mystery. There was no William in Vincent’s immediate family, and there never was any other Molyneaux mentioned in any of the Evening Journal game accounts throughout the season. The newspaper added to the mystery, though, in its August 25 edition when it reported "Secretary Molyneaux of the Jamestown club announced this morning that he had booked the Newark club" for an exhibition game on August 30. Secretary Molyneaux? Some relative was a team executive? There is nothing in any of the other sports page coverage that year that referred to a Secretary Molyneaux. Further, the team that Jamestown played on August 30 was Jersey City, not Newark. It was perhaps a simple mistake of some sort.

Molyneaux had won a baseball scholarship to Villanova College in Pennsylvania and was a standout pitcher for Villanova in both 1915 and 1916, first raising eyebrows with a 14-inning 1-1 tie with Fordham on May 25, 1915. A "Philadelphia expert" cited by the Washington Post in June 1915 listed his "all-star" choices for an All-Eastern baseball team. He selected Harvard’s Eddie Mahan as pitcher, but said that some of the other contenders lacked a good team behind them, adding, "Molyneaux, of Villanova, with a star nine, would have shown almost as well as any pitcher who can be mentioned."

Mysteries continue to confound. It’s not clear why Jamestown let him go but Molyneaux was released to Wellsville, also in the Interstate League, for 1915. Inexplicably, the National Board canceled the deal (a handwritten note in Molyneaux’ Hall of Fame files indicates he was suspended) and he never played for Wellsville. He is shown as having signed with a team in Buffalo instead, in June 1915, but never played for Buffalo, either. He was released to the London (Ontario) Tecumsehs (in the six-team Canadian League). Molyneaux joined a team in a bit of turmoil. Players were coming and going, and the London club in particular was under financial constraints worse than those of the other teams. Frustrated manager F.C. “Doc” Reisling, who often pitched for the team, too, at one point grumbled that London was “used to $1,800 a month baseball” but owner A.E. Somerville had placed a stricter salary cap on his ballclub. The Tecumsehs (they played in London’s Tecumseh Park) began the season with 16 players on the roster, but by June 28 were down to just 11 players and Reisling!

On July 7, Reisling telegraphed the London Evening Free Press that he had obtained “a pitcher by the name of Mulina, with a fine college reputation.” Due to pitch his first game on July 8 against the St. Thomas (Ontario) Saints, he “received the sad news of his sister’s sudden death in New York State” and so left the club before he had a chance to throw a pitch. Instead, the Tecs signed Tom “Julius” Caesar. Our man returned, though, and got his first start on July 17. Described in the Free Press as “Mike Mulina” he was removed in the fifth inning after giving up three runs on five hits, but he had been working with a big enough lead that London beat the Brantford (Ontario) Red Sox nonetheless, 6-5. Throughout the season, which ended on September 1, the London newspaper consistently spelled his name as Mulina, though one or two box scores showed him as “Molina.” Apparently, Molyneaux never read the newspaper or never bothered to correct it.

He started again on July 23 and last-place London lost a close 3-1 game to first-place Ottawa. Three errors hurt the London team. Winning against Hamilton, 3-2, in his next outing, three days later, he displayed “fine form.” Eight errors (!) cost him the July 31 game against St. Thomas, despite combining with pitcher Hammond on a five-hitter, only one of which was charged to “Mulina.” He allowed six hits and lost a fine 1-0 effort to Brantford on August 2; three bunched hits in the sixth sealed his fate.

On August 4, London named second baseman Wally Hartwell as manager, replacing Reisling; the newspaper said Reisling was “not a driver…he might have got better results had he refrained from treating some players like human beings.”

The next day was a spectacular one for “Mike Mulina.” He pitched both halves of a doubleheader against the Guelph (Ontario) Maple Leafs and nearly won them both. Only a bad first inning in the first game (six runs scored while he was “wild as a hawk” before settling down) prevented him from winning both. After the one bad frame, he allowed just three runs for the rest of the day. London lost the first game, 8-5, and won the second, 3-1. He was 2-for-7 at the plate.

On August 9, he won an efficient 6-0 shutout and then beat St. Thomas 9-1 just five days later. An August 18 pitch buzzed by the head of Ottawa pitcher Urban Shocker (“Herb” Shocker in the London paper) and he had words with Molyneaux, who charged the Ottawa batter and hit Shocker in the face. Shocker came back with a couple of haymakers before the two were separated. The Senators won the game, 2-1. Late in the year, there was one game when “Mulina” played right field, batting ninth, going 0-for-3 at the plate, and never making a play on a ball. On the final day of the year, he won a three-hitter against St. Thomas, 3-0, on a day when both games of the doubleheader were completed in one hour and 55 minutes.

Molyneaux finished the year with a 6-4 record on the mound and a .162 average (6-for-37) at the plate. All six hits were singles. As far as Free Press readers ever knew, however, this was the record of a man named Mike Mulina.

Vince pitched for Villanova again in 1916, and had a record of 8-4. The Boston Globe first took notice on June 6, 1916, with a story headed "Red Sox in the Bidding." The story, filed from Philadelphia the day before, reported "Vincent Molyneaux, star pitcher of the Villa Nova [sic] College baseball team, who has bested the University of Pennsylvania, Penn State, and other strong college aggregations this year, has received five offers from major league clubs." The report ended, "Molyneaux, who is a big right-hander with speed, good curves, change of pace, and an easy pitching motion that should make him last for years if he proves good enough to stay in fast company, has just completed his sophomore year at Villa Nova, but is willing to play professional ball if he gets what he considers a fair offer." Both Philadelphia teams, the White Sox, the Red Sox, and the Cincinnati Reds had all expressed interest.

"He was one of those students who favored summer ball," reported the Chicago Tribune‘s James Crusinberry in his special report from Philadelphia on July 14, and found Molyneaux more than ready to play. According to Crusinberry, Molyneaux had just graduated from Villanova and was looking for a job with the White Sox. The writer’s story said, "When the Sox arrived, they found a new pitcher waiting to become one of them….Immediately after lunch the recruit went to the ball park and was fitted up with a big league suit. He was to be allowed to pitch to the batters during their practice session, but the rain spoiled his chance. He will work out tomorrow before the eyes of the manager and will do the same for several days. If he shows class he may be retained or farmed to some minor league team to get experience."

Apparently, he hadn’t graduated, since he’s found pitching once more for Villanova on May 3, 1917, throwing a three-hitter against the University of Pennsylvania – but losing 3-0. Not too long after school ended he was brought into the St. Louis Browns offices and, after a conference with manager Fielder Jones, signed a contract at the behest of his escort, Browns scout Charlie Kelchner. Pitchers Eddie Plank and Tom Rogers were both ailing and the team needed some help.

The signing was announced on June 7 and Molyneaux debuted at home against the visiting Cleveland Indians on July 5, just a few weeks before he turned 29. He pitched very well in relief, allowing just two hits and one run in five full innings, but granting four bases on balls in the process. He struck out two. Thrown into the game the next day, too, Molyneaux walked two more and gave up three hits, tagged for two earned runs in 2 2/3 innings of middle relief. On July 11, Molyneaux walked five more batters and gave up four hits in another five innings, charged with three earned runs. On the 15th, facing the Boston Red Sox, once more he pitched in middle relief (the Browns lost every one of these games). He pitched the eighth, allowing just one hit, but when he walked the first two Red Sox in the top of the ninth, he was pulled from the game. The next pitcher induced a double play and got out of the inning; neither runner scored, and the game ended in a 6-3 defeat for the Browns.

Molyneaux, though, was hardly “lights out” as a reliever, and it appears he worked throwing batting practice awaiting another appearance for nearly six weeks. Vincent next pitched the ninth inning in an 8-0 August 27 loss to Philadelphia, with one walk, one hit and three runs (one earned) in one inning of work. During the August 30 game in Chicago, he took over as the third Browns pitcher after the first two yielded six runs in the first two innings. St. Louis manager Fielder Jones "sent a kid named Molineaux [sic] to the slab." Vince completed the game, allowing two runs in six innings, walking four and striking out two, giving up six hits, but batting 0-for-2 at the plate.

In Cleveland on September 3, he came on in middle relief during the morning game and was ineffective, with two walks and two hits in 1 1/3 innings – allowing a few more runs. He threw a wild pitch and struck out one. He compiled a 4.91 ERA in 22 innings of work, gave up 18 hits and 15 runs (12 earned). His strikeouts-to-walks ratio was the inverse of the desired one: he struck out four but walked 20.

At the end of spring training 1918, as he was leaving St. Louis to go with his team to open the season in Chicago, Browns business manager Bob Quinn gave Molyneaux his unconditional release, announced on Opening Day, April 16. The St. Louis Star wrote, “An over-abundance of right-handers on the Browns resulted in his release.” The Cardinals pounced and signed him the same day. Branch Rickey had his eye on “the collegiate hurler” (as he was described by the St. Louis Post-Dispatch) the year before but had lost out when Vincent had been signed by the Browns. The Cardinals were in financial straits; at one point in the first half of May they were down to 17 players on the team, and Rickey was wheeling and dealing. Still, Molyneaux failed to sufficiently impress; he was given his release on May 7 and the Star politely wrote, “As manager Hendricks’ pitchers have been hurling good ball, he was unable to find a place for the former collegian.” Apparently the team "tried to place him with in a minor league" but Vincent may have declined, hoping instead for another shot at “The Show.”

If such was his plan, it may have paid off. Two weeks after his release, on May 21, Boston’s Ed Barrow announced the signing of "Molyneaux, the former crack Villanova right-hander." The brief report in the Boston Globe said, "Molyneaux recommended himself to the Sox and as some of the Boston players had seen him in action, Barrow decided to take him on. He will report today or tomorrow." He reported in Boston on the 23rd, and was immediately put to work pitching batting practice. That may have been the reason Barrow signed him. A July 24 comment in the Boston Herald indicated he was a pitcher "Ed Barrow picked up because he had absolutely no practice-flingers."

He got a chance to play, though, and his Red Sox debut came in Boston during the second game of a Memorial Day morning/afternoon doubleheader against Washington. The Red Sox won the first game with ease, 9-1, but Dick McCabe allowed four runs in eight innings and the Red Sox failed to score in the second game. Molyneaux pitched the ninth inning without allowing a man to reach first base.

On June 7, the Indians worked 11 walks off six Red Sox pitchers and slammed out 13 hits and took the game, 14-7. Neither Dutch Leonard nor Joe Bush, nor Babe Ruth, nor “Victor” [sic] Molyneaux, nor Sam Jones, nor "McCabe, a batting practice hurler" could stop them. Molyneaux walked two and threw two wild pitches in his 2/3 of an inning, but didn’t give up a hit.

He appeared in the second game of a June 20 Fenway Park doubleheader and walked a couple of batters but helped preserve Leonard’s 3-0 shutout of the Athletics after Tillie Walker’s line drive injured Leonard’s hand in the sixth and forced him to leave the game. Molyneaux came on in relief and threw 3 2/3 innings of hitless relief, picking up his only major league decision – a win – when the Red Sox scored all three of their runs in the bottom of the sixth.

On July 3, Lore Bader started the game and threw the first seven innings, allowing five runs. Red Bluhm batted for Bader in the top of the eighth (Bluhm’s only appearance in a major league game), and Vince pitched the bottom of the eighth – the two hits and a walk, and one run made little difference in the 6-0 Philly win. The next day – Independence Day – Vince took over for Sad Sam Jones in the sixth inning of the first game in Philadelphia and got the Sox out of the inning before Joe Bush took over for him in the seventh. Vince walked two but didn’t give up a hit. He was "hit hard" in a July 14 exhibition game against Queen Quality of Jamaica Plain, though the Sox won the Woonsocket, R.I., game, 5-2.

The Browns beat the Red Sox on the 18th, and "Molly" (as the Boston Record called him) threw the final three innings, allowing just one hit and one run on a walk, a sacrifice, and a single. His outing earned him a subhead in the Boston Daily Advertiser: "Molyneaux Does Well When Given Chance to Finish Game." The paper called him Mike Molyneaux; the London paper had called him “Mike” as well; Vince and Squinch and Molly were not his only nicknames. At the plate for the Red Sox, he’d batted only twice and struck out both times. When it was his turn to bat in this game, there was one out in the Boston ninth. Barrow had Carl Mays, another pitcher, hit for him, and Mays ended the game by grounding into a double play.

The next day, July 19, Molyneaux was given his outright release to the Jersey City Skeeters (International League). Molyneaux balked, though, and said he would not go. The Boston Herald wrote, "Vincent had a chance to go to the Jersey City team but passed it up and got the blue envelope instead." The July 20 Globe reported: "Molyneaux says that the Red Sox did not have to pay a cent for him, that he wrote asking for work and they signed him. He says that they have no right to sell him now and he intends to make an issue of the matter. He insists that he has the goods as a big league pitcher and knows of several clubs that will give him employment if he becomes a free agent. What work Molyneaux has done for the Sox he did well." It’s true he was 1-0 with a 3.38 ERA in 10 2/3 innings of work, and had only given up three hits to the 43 batters he faced, but (as with the Browns) he had an "upside-down" walks to strikeouts ratio (one strikeout, eight walks), and threw two wild pitches. There was at least one untoward moment after his release. "Molyneaux says that an effort was made to bar him from the clubhouse yesterday," noted the Globe.

Even if there were several other clubs interested, Molyneaux suffered from poor timing – the next day Ban Johnson ordered all American League ballclubs to cease operations within 48 hours. Though his order never went into effect, it was just a week after Molyneaux’ release that Secretary of War Baker announced that the baseball season should end on September 1. Teams were not looking for new players, and one could hazard a guess that announcing plans to "make an issue" regarding his employment would not have endeared him to the magnates of the game under any circumstances.

Vincent returned to Niagara Falls in 1918 and went to work for "the Aluminum company" – likely a job he undertook as an alternative to military service during the World War. Molyneaux pitched one inning for the Salt Lake City Bees (Pacific Coast League) in 1919. He’d been acquired in March and the Salt Lake Herald reported manager Eddie Herr was "sweet on pitcher Molyneaux." Herr had worked as a scout for the Browns and knew Molyneaux, who joined the Bees during spring training on March 23. He was apparently not in the best of shape, as a Herald note on April 5 reported him having the only sore arm in camp; a week and a half later, the Salt Lake Telegram reported his arm giving him "considerable trouble." An earlier report in the April 15 Herald described Molyneaux (and his windup) as "the man with the ‘special delivery’ – a style that is all his own." He had a spitter as well "that it is declared has some stuff on it."

His one inning late in the April 24 game against Los Angeles was far from successful: he retired no one, allowed two earned runs, and lost the game. The winning pitcher was former Red Sox teammate Bill Pertica. It was a bad outing, and Bees manager Herr wasn’t in a patient mood. Writing in the Los Angeles Times, Harry A. Williams told the story: "Monsieur Molyneaux started. That remark about covers his career. M. Molyneaux began slipping as soon as he started, and didn’t stop until he had slipped clear out of the park." The first batter he faced was Red Killefer, who walked. Then he threw a wild pitch that was so wild that Herr apparently shouted, "Come out of that!" Williams wrote that the Salt Lake manager’s "anguished bellow could be heard all over the park." There was no one warming up. Herr just wanted him out of there. The final score was 7-1, Los Angeles, so Molyneaux took the loss. It was his windup that caused concern, one that Williams called an "eight-day windup." The game story said Molyneaux "has a most complicated delivery, indicating that he is an athlete of complex mechanism. …When he would finish winding up, he appeared to have lost his sense of direction, not being sure whether [first baseman] Earl Sheely or [catcher] Tub Spencer was behind the plate. So he played safe by throwing the ball into neutral territory." Even though relief pitcher Schorr finished walking the second Angels batter, the walk was assigned to Molyneaux. Both runners subsequently scored.

Herr already had his eye on a replacement, and wasted little time making a move. The Salt Lake Herald headlined its story: MOLYNEAUX JERKED OFF RUBBER AFTER SKYSCRAPER THROWS: IS RELEASED. Researcher Craig Fuller offered some detail from the paper’s account: "Weird pitching cost Salt Lake the game today. It also cost pitcher Molyneaux his job after he had tossed up six consecutive balls, the last of which was ten feet above Spencer’s head. Manager Herr wigwagged him from the mound and thereupon decided to release him." Al Gould joined the pitching staff the next day, and Molyneaux was reported heading back east.

It was Molyneaux’s last appearance in professional baseball. A May 15 Reading Times article reported – it was deemed headline material – "Vin" Molyneaux had arrived in Reading and had agreed to terms offered him by the Reading ballclub’s assistant manager, Charlie Kelchner. Molyneaux had wisely sought out Kelchner, the scout who’d signed him to the Browns two years earlier. The team was on the road at the time and Kelchner wired manager Red Dooin asking whether Molyneaux should join the team or await their return. Just two weeks later, without ever appearing in a game for Reading, he was released. The May 29 Times explained, "His arm is not in shape and the team could not afford to carry him along."

It was apparently not long after his abortive attempt to continue in baseball that Molyneaux began work as an auditor with the United States government. He developed a heart condition in 1949 and died on May 4, 1950, in Stamford, Connecticut. The death certificate describes him as a "retired traveling accountant U. S. Gov. R. F. C." and indicates he had been living in Stamford for two years. (R.F.C. almost certainly refers to the Reconstruction Finance Corporation [1932-1957.]) The city directory in Stamford shows him as living at 369 Atlantic Street in 1950 – the address was, at the time, the address of the YMCA. Molyneaux had been married earlier in life, but his obituary indicates he was survived only by two cousins, Mrs. Samuel Johnson and Mrs. Harold Flynn. Funeral services were held at Sacred Heart Church in Niagara Falls, and he was buried at St. Mary’s Cemetery. The Niagara Falls Gazette obituary described Molyneaux as "probably one of the finest hurlers in baseball history in Niagara Falls.

Sources

The various sources consulted are mentioned throughout the text. Thanks to Jon Dunkle, Tom Darro, Marty Friedrich, Brian Engelhardt, Ed Washuta, Ray Nemec, Greg Spira, Grace Bounty and the Stamford Historical Society, Craig Fuller, Steve Steinberg, Maurice Bouchard, and the Cambridge Public Library.

Full Name

Vincent Leo Molyneaux

Born

August 17, 1888 at Lewiston, NY (USA)

Died

May 4, 1950 at Stamford, CT (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.