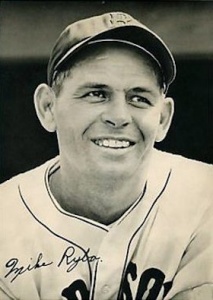

Mike Ryba

Arthur Daley of the New York Times once wrote that Mike Ryba had been “too good for his own good.”1

Arthur Daley of the New York Times once wrote that Mike Ryba had been “too good for his own good.”1

One way or another, Mike Ryba seemed to be associated with saints for a great part of his life. He went to St. Adrian’s in DeLancey, Pennsylvania, a coal-mining town of about 2,000 people, for his first eight grades of schooling, then graduated from St. Adrian’s High School. He attended St. Francis College at Loretto, Pennsylvania, for two years. When it came to baseball, he was signed by the St. Louis Cardinals and played in their farm system for a couple of years, even managing for a year before debuting in the big leagues, for St. Louis, in a home game at Sportsman’s Park. Though he spent several years pitching for the Boston Red Sox, he returned to St. Louis to manage in the minors and scout for the Cardinals.

Over 10 seasons, Ryba pitched in 240 major-league games; he was 52-34, with a 3.66 earned run average. He was also known as a “one-man team” for his ability to play any position on the field, and was thought to be the only player who both pitched and caught in the National League as well as in the American League. There was even one day he both pitched and caught for the Cardinals (not at the same time.)2 In the minors, he pitched in a known 204 games and caught in 406.

Daley’s quote reflected what had become accepted wisdom. He wrote, “Perhaps Mike was a bit too good for his own good. He never did settle down to one position.”3 His very versatility made him exceptionally desirable at the minor-league level, but the fact that he never honed his skills at any one task likely held him back from success in the majors. It was something he himself understood. “I could play any position and this made me pretty valuable in the minors,” he once said. “If I had specialized in pitching – or at another position – I think I’d have been more successful.”4 Looking back late in his career, he said he thought it “was more hindrance than help” to his career.5 He was nonetheless content. When he’d first joined the Red Sox, he said, “After you have stood in soft coal up to your waist, you want to stay in baseball just as long as you possibly can.”6 He said, “I used to dig 20 tons of coal a day and then come up and load it, and then pitch a ball game.”7 He told the Washington Post’s esteemed sportswriter Shirley Povich, “Listen, sonny, you know what I call my baseball career? Well, I call it a 16-year vacation from the coal mines.”8

DeLancey is where Dominic Joseph “Mike” Ryba was born, on June 9, 1903. His father, Peter, was a coal miner who had come to the United States in 1890 from Austria. Mother Marcella (Maciejewski) was from Russia and she arrived in America in 1901. The two were both Polish speakers, the separate countries of origin as listed in the United States census reflecting the changing geographic boundaries of the times. In Polish, the word “ryba” translates to “fish;” his surname was pronounced “ree-ba.” Marcella bore six children; Dominic was the second. At the time of the 1920 census, his older brother Joseph worked in the coal mines. Dominic himself worked in the mines, even during the off seasons in his earlier minor-league years. He also worked on a section gang for a streetcar company in Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania (of Groundhog Day fame), and as a laborer on the railroad.9 In a Boston Globe story after Ryba’s death in 1971, Harold Kaese wrote that Ryba had also worked as a conductor and suffered a horrendous head-on trolley crash which put him in the hospital for five months, where he read a newspaper account saying he had died.10

His first pitching in the minors was for the Wheeling Stogies in 1925, at age 22.11 He seems to have played semipro ball for a number of years before signing with Syracuse in December 1927. At the time, the news release out of his hometown of Punxsutawney said he had “played on local teams for several seasons.”12 Instead of Syracuse, he wound up as a regular with the Dayton Aviators in 1928, pitching to a 13-13 record in the Class-B Central League. It was noted that he was “originally signed by the St. Louis Cardinals.”13 Bob Broeg told an anecdote regarding his signing with the Cardinals. Scout Pop Kelchner presented him a contract that winter, but weeks later the Cardinals reached out to ask Ryba what was wrong with the contract. Nothing at all, he wrote back. “Then why don’t you sign the contract and report?” he was asked. It hadn’t occurred to him, Broeg wrote, that a contract was something he had to sign.14

When not pitching, Ryba (known as Don or Dom Ryba at the time) sometimes played other positions. He’s seen in box scores in both corner outfield positions and in the July 17 game against Canton, he pitched and, when relieved, played third base and shortstop.

He trained with the Cardinals in the spring of 1929, but spent the season with Waynesboro (4-2) and Scottdale, Pennsylvania, where he was 10-1, batting .440 in 75 at-bats. Back in Scottdale in 1930, he was 3-3 in 11 games as a pitcher – though he appeared in 110 games overall, batting .356. After the season, he was named league MVP. Before reporting to Scottdale, he had one at-bat in one game for Rochester, a Cardinals affiliate. His versatility was noted in September 1931 (he hit .342 in 114 games for the Class C Springfield (Missouri) Red Wings. An Associated Press release said that the catcher substituted “in both infield and outfield on occasion [and] took to the mound and pitched three victories”15 He was 3-0 on the mound, and again MVP of the league.

In 1932 he played for the Class-A Houston Buffaloes, appearing in 64 games, but batting .205 at the higher level of play. It seems to have been an anomalous season, since he was back in Class A in 1933 (with Springfield, which had been raised to a higher classification) and hit .380 in 114 games, leading the Western League.

Springfield was renamed the Springfield Cardinals in 1934, and reclassified back to Class C. Mike Ryba was the manager, and there were even more demands on his versatility. He sold tickets, rubbed down the pitchers, would move from catcher to first base during a game if the situation demanded it, and just generally did whatever needed to be done. “I not only handled the club but also drove the bus,” he recalled in 1948. “It was a battered thing that in a safety crusade might have been ruled off the highway. But we had to get to our destination so I got behind the half-choked motor and coaxed her along. Sometimes we didn’t quite make it.”16 He assigned himself to play in 119 games and hit for a .327 average. He was also 12-3 with a 2.96 earned run average. The team won the league pennant and the playoffs.

And 1935 was a very good year, too. Though he didn’t manage the team, he became a 20-game winner (20-8, 3.29 for the American Association’s Columbus Red Birds, while batting .318 in 94 games), and was called up to the big leagues in time to hit .400 (2-for-5) and win a game.17 He was named American Association MVP.

Ryba’s major-league debut came on September 22 against the visiting Cincinnati Reds. Ryba pitched a full seven innings of relief after Cards starter Bill Hallahan had coughed up three early runs and was removed for a pinch-hitter in the bottom of the second inning. St. Louis won the game, 14-4. Ryba only allowed two hits and walked one while collecting two hits himself and driving in three runs. What more could one want? A late bloomer, Ryba was 32 years old at the time of his debut (though at the time, he was thought to be two years younger}.

On the 27th, he threw a complete game against the Cubs in the second game of a doubleheader, but lost, 5-3. (The Cubs had clinched the 1935 pennant with their win in the first game.) Ryba finished the season 1-1, batting .400. He did a little barnstorming after the season with Paul and Dizzy Dean, and was married on November 1 to Thelma Howell of Springfield, Missouri.

Mike Ryba started the 1936 season with St. Louis, but had a 7.20 ERA after his first 10 appearances and was released on June 2 to get the roster down to the 23-player limit. Sent to Columbus, he was 14-7 with a 4.03 ERA. He was brought back to the Cardinals and won games in three of his four appearances.

In 1937 he spent the full season with St. Louis, appearing in 38 games (eight starts), 9-6 (4.13 ERA). He hit .313 (the year before, he’d hit just .167.) In 1938, he only threw five innings, and was optioned to Columbus on June 17. Columbus was challenged offensively, and even though Ryba pitched to a 3.24 earned run average, his won/loss record was 3-9.

The next time Ryba reached the major leagues was almost three years later, in 1941, though he had two very good years in Double-A ball with the International League’s Rochester Red Wings, with records of 18-12 in 1939 and 24-8 in 1940, with ERA’s under 3.00 both years. Rochester won the playoffs in 1939 (though they lost the Little World Series), and the pennant (but not the playoffs) in 1940. Unsurprisingly, he led the league in wins and was the I.L. MVP – the fourth year he was named MVP of his league. On September 5, 1940, the Boston Red Sox bought his contract for an unannounced sum (thought to be $17,500) and a player to be named later. Though aware that he was 35 years old, Red Sox manager Joe Cronin allowed that he “looked like the best prospect he had seen.”18 When he joined the team the following spring, the aging Lefty Grove nicknamed him “Pop.”19

Ryba was willing to do anything. He said, “I might have made a pretty fair catcher if I had stuck at it. What difference does it make so long as you can help out?”20 He said he realized he probably could have helped out the Cardinals in 1940, but they really needed him more in Rochester. When the Red Sox signed him in early September, they wanted him for immediate delivery, but Rochester wouldn’t agree.

The American League was the tenth league in which he played. The Red Sox envisioned him as a pitcher, and indeed even in practice when he wasn’t on the mound he spent most of his free time in the bullpen. His first game was a start, in Washington on April 20. It wasn’t his best performance, yielding four runs in six innings, but he won the game. By the end of June, he was 5-1 and by the end of the year he was 7-3 (4.46), working mostly in relief.

Older than draft age, he didn’t have to worry about being called into military service. He wasn’t used as much in 1942 (3-3 in 18 games – and he caught three games, too) but in both 1943 and 1944, he worked in at least 40 games (7-5 and 12-7). Ryba was a significant part of the pennant push the Red Sox put on in 1944. As of June 8, he was 6-1 – despite not starting a single game, he was the league’s most-winning pitcher. He was 7-6 with a 2.49 ERA in 1945. Ryba was a fan favorite, and at the end of 1945 the Bull Pen A.C., a 200-member strong group of bleacherites, held their fifth annual dinner at the Parker House, honoring him with a gift of $500, which was matched by Sox GM Eddie Collins.21

Admittedly, Ryba was facing depleted offense during the World War II years, but in his six seasons with the Red Sox, he recorded an overall 3.41 ERA and a record of 36-25. The only year he had a losing record was his last year in the big leagues, 1946, when he was 0-1, battered for four earned runs in one-third of an inning on April 23. He appeared in seven more games after that, allowing just one earned run over the stretch. The Red Sox were cruising on their way to the American League pennant and really didn’t need him on the mound. His final regular-season inning was thrown on August 29.

Ryba did appear once in the World Series, in the ninth inning of Game Four. The Cardinals already had a 9-3 lead at that point and there were runners on first and second with nobody out. A sacrifice bunt moved up the baserunners and Marty Marion doubled them both in. A groundout was followed by Ryba’s own fielding error. A single and a walk followed, and he was taken out. Though it didn’t materially affect the result of the game, it was a discouraging end to the dream of playing in a World Series, and to his career as a major leaguer.

Ryba batted 1.000 in the 1946 season, 2-for-2. His lifetime batting average in the big leagues was .235 (.297 on-base percentage) with 24 RBIs in 290 plate appearances. One of his most memorable runs batted in came when, after throwing three hitless innings of relief, he singled in the winning run in the 12th inning of the May 19, 1944, game against the visiting White Sox.

Despite having started his career so belatedly, he still had put in enough time to qualify for a pension.

In 1947, Ryba managed the Lynn, Massachusetts, affiliate of the Red Sox in the New England League, but gave himself a little work and put up a 3-3 record. He managed Scranton in 1948 (winning the Eastern League flag) and some of 1949, going on during the season to manage the Louisville Colonels in ’49 and 1950.

It’s not known quite what happened, but at the start of December Ryba was told his services were no longer wanted. “It happened so fast and without explanation,” he told the Boston Globe’s Hy Hurwitz. “One day last week Joe Cronin called me and told me that I was to manage Louisville in 1951. The next day he called me and told me that he wanted my resignation. He told me that he had granted permission to Fred Saigh (owner of the St. Louis Cardinals) to talk to me about a new job.”22

A few days later, Saigh did hire him and from 1951 through 1954, Ryba worked in the majors as a coach for the St. Louis Cardinals.

Around 1952, Thelma Ryba broke her hip and it refused to heal properly despite three operations. She used a cane but kept teaching school so that she and Mike could help the three Ryba children – Mike Junior and two daughters — get through college.23 Starting in the winter of 1943, Mike had worked a couple of off seasons as a policeman in Springfield, “but I finally had to quit…Found out you can’t be a good fellow and a cop, too. I’d rather be a good guy.”24

In 1955 he managed the Houston Buffaloes in the Cardinals system. Ryba scouted for St. Louis from 1956 through 1959, while being asked to manage Ardmore for part of the season in 1957 and York for part of 1959. The Cincinnati Reds hired him to scout from 1960 through 1962. In 1963 the Reds had him manage their Cedar Rapids team in the Midwest League. He was back scouting for St. Louis on a part-time basis in 1964, and fulltime from 1965 through the 1971 season.

Ryba was working at his home in Springfield, Missouri, on December 13, 1971, trimming tree limbs, when the footing of the ladder slipped and he grabbed a tree limb, which broke. He fell to the ground, landing on his back, and was fatally injured. He crawled about 40 feet and that is where his wife Thelma found him on her return home from teaching at Hillcrest High School. The coroner in the case was Greene County Sheriff Mickey Owen, who’d been a teammate of Ryba’s in Columbus in 1936 and then with the Cardinals in 1937 and 1938.

Owen explained how, as a ballplayer, Ryba had been “a victim of his own ability.” A number of minor-league clubs in those days drew as well as the major-league clubs, and sometimes the minor-league clubs made money for the organization while the big-league clubs lost money.25 Ryba was too valuable to some of those clubs to let him advance to the majors.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Ryba’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, Rod Nelson of SABR’s Scouts Committee, and the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Arthur Daley. “Reversible Battery,” New York Times, March 30, 1956: 29.

2 The game was reportedly in 1933, for Springfield, and it was a stunt – he played one inning at each position. Tom Ruane, of Retrosheet and SABR, points out that the calculation missed Roger Bresnahan, who had pitched and caught in both the AL and NL by 1901. The two players who have done it since are Jimmie Foxx and Drew Butera. Tom adds, “It happened several times in the 19th century and King Kelly pitched and caught in 3 different leagues (NL, PL and AA).”

3 Daley, “Reversible Battery.”

4 Dominic (Mike) Ryba obituary, The Sporting News, January 1, 1972: 46.

5 Arthur Daley. “Unprotected Investments,” New York Times, April 1, 1964: 30.

6 Boston Red Sox press release, March 1941. A copy is in Ryba’s player file at the Hall of Fame.

7 Shirley Povich. “Ryba Blasts Major Leaguers for Griping,” Washington Post, March 24, 1954: 29. His father had worked 45 years in the mines, he said, and then couldn’t take 20 steps due to “miner’s asthma,” what we today call Black Lung.

8 Shirley Povich. “This Morning; Introducing the One-Man Gang,” Washington Post, April 16, 1941: 23.

9 Irven C. Scheibeck. “Rickey to Introduce ‘One-Man Team’ to Major in Mike Ryba, a Catcher with 17 Mound Victories,” The Sporting News, September 5, 1935: 2. See also E. G. Brands, “Ryba Named Most Valuable in Fourth League,” The Sporting News, October 17, 1940.

10 Harold Kaese. “Ryba gave his all until the end,” Boston Globe, December 15, 1971: 51. Kaese’s story said that one of his brothers had lost an arm after falling from a scaffolding, and that Ryba had seen eight men electrocuted by a live wire.

11 Ed Rumill. “Baseball Scouting ‘An Auction Today’,” Christian Science Monitor, February 14, 1963: 14.

12 Associated Press. “Syracuse Signs Pitcher Ryba,” New York Times, December 28, 1927: 20.

13 “Veteran Bobby Schang with Aviators As Catcher,” The Repository (Canton, Ohio), April 13, 1928: 46. Jack Malaney of the Boston Post wrote a very lengthy article on Ryba, which appeared in the April 17, 1941 Sporting News and in which he said it was indeed in the fall of 1927 that Kelchner had seen Ryba playing in a semipro league and gotten him to agree to a contract.

14 Bob Broeg. “Old Man Ryba of Red Sox Is Baseball’s One-Man Team,” Kansas City Star, August 30, 1942: 20.

15 Associated Press. “One-Man Ball Team,” Boston Globe, September 9, 1931: 6.

16 Chic Feldman. “Dust Bowl Traveler Ryba Remembers Well,” Scranton Tribune, September 23, 1948. The article recounts a story when a dust storm had canceled their game at Hutchinson, Kansas, so he started to drive for home but the axle “conked” and he had to charter a city bus out of Wichita.

17 Actually, on top of everything else, Ryba did briefly manage the Redbirds at one point in August while manager Ray Blades served a suspension.

18 He was, of course, 37. See Gerry Moore, “Red Sox Buy 35-Year-Old Pitcher, Ryba, and Vet Shortstop, Newsome,” Boston Globe, September 6, 1940: 23. Moore added that Ryba was “a colorful character as evidenced by the fact that he now resides during the off-season in the Panama Canal Zone.” He taught baseball in Panama for two winters.

19 Associated Press. “Grove Calls Ryba ‘Pop’,” Lexington (Kentucky) Herald, February 26, 1941: 15.

20 Jack Malaney. “Roaming Mike Ryba, the Man Everybody Knows, Rolls Back to Majors in Stating Pitcher Role for Red Sox,” The Sporting News, April 17, 1941: 3.

21 “Mike Ryba Feted by Bull Pen A.C., Gets $1000 Gift,” Boston Globe, September 23, 1945: D31.

22 Hy Hurwitz. “Mike Ryba Says Cronin Asked Him to Resign,” Boston Globe, December 4, 1950: 7.

23 Bob Broeg. “Ryba, Baseball’s ‘One-Man Gang,’ On Sidelines First Time Since ’25,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 15, 1964.

24 Associated Press. “Mike Ryba Willing to Fill Any Post for Bosox,” various newspapers, March 24, 1945. Unidentified clipping in Ryba’s Hall of Fame player file.

25 “‘One Man Ball Team’ Mike Ryba Dies Following Fall From Tree,” unidentified local newspaper clipping found in Ryba’s Hall of Fame player file. Harold Kaese’s December 15, 1971 story in the Boston Globe said he was trimming the tree in preparation for Christmas.

Full Name

Dominic Joseph Ryba

Born

June 9, 1903 at DeLancey, PA (USA)

Died

December 13, 1971 at Brookline Station, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.