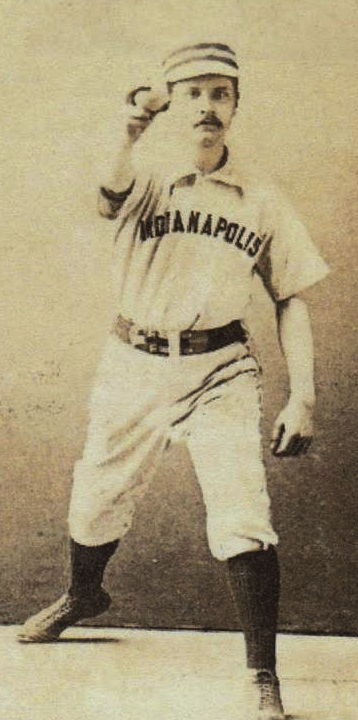

Lev Shreve

Right-handed pitcher Lev Shreve was a nineteenth-century baseball rarity: an affluent young man descended from a distinguished and prosperous family whose American roots dated from the late 1630s.1 Early generations included settlement founders, Revolutionary War heroes, judges, lawyers (including a reputed law partner of Thomas Jefferson), civic leaders, and the founders of Shreveport, Louisiana. Lev’s branch of the family moved from Maryland to Kentucky in the late 1790s and included founders of the city of Louisville. His immediate forbears focused on banking, mining, and other forms of commerce that enhanced the family’s already considerable fortunes.2 Regrettably for Lev, a moneyed patrimony did not guarantee success in baseball. For three major-league seasons, the marginally talented Shreve labored, posting a dismal won-lost record that roughly coincided with that of the woeful Indianapolis Hoosiers, the short-lived National League franchise that Lev spent most of his time in uniform with. Jettisoned by the game while still in his mid-20s, Shreve spent the remainder of his long life in more family-typical circumstance as an executive in the automobile industry and the administrator of family estates.

Right-handed pitcher Lev Shreve was a nineteenth-century baseball rarity: an affluent young man descended from a distinguished and prosperous family whose American roots dated from the late 1630s.1 Early generations included settlement founders, Revolutionary War heroes, judges, lawyers (including a reputed law partner of Thomas Jefferson), civic leaders, and the founders of Shreveport, Louisiana. Lev’s branch of the family moved from Maryland to Kentucky in the late 1790s and included founders of the city of Louisville. His immediate forbears focused on banking, mining, and other forms of commerce that enhanced the family’s already considerable fortunes.2 Regrettably for Lev, a moneyed patrimony did not guarantee success in baseball. For three major-league seasons, the marginally talented Shreve labored, posting a dismal won-lost record that roughly coincided with that of the woeful Indianapolis Hoosiers, the short-lived National League franchise that Lev spent most of his time in uniform with. Jettisoned by the game while still in his mid-20s, Shreve spent the remainder of his long life in more family-typical circumstance as an executive in the automobile industry and the administrator of family estates.

Leven Laurence Shreve II was born in Louisville on March 12, 1866,3 and was named for his recently deceased great-uncle, a utilities and railroad company president.4 Lev was the seventh and final child born to Charles Upton Shreve (1828-1916), a wealthy law school-educated businessman and the overseer of Shreve family interests, and his wife, the former Sallie Benbridge McCandliss (1834-1905).5 Lev grew up comfortably and attended Louisville Academy through high-school graduation.6 He began playing baseball in his youth, the disapproval of his father, notwithstanding.7 Tall for his time but lightly framed (5-feet-11, 150 pounds), Lev gravitated toward pitching, with a fine drop becoming his out pitch.

Whether Lev was the Shreve who tried out for but was released by the Columbus (Georgia) Stars of the Southern League in April 1885 is unclear.8 Whatever the case, Shreve began his professional career in earnest the following spring, signing with the Chattanooga Lookouts, also of the Southern League. Days before the Chattanooga club disbanded on July 9, league rival Savannah purchased the release of Shreve and catcher Tug Arundel for $500.9 There, Lev completed a 12-9 season record, with an excellent 1.52 ERA. Later, he did some postseason pitching for Milwaukee in the Northwestern League and the R.E. Lee (New Orleans) club of the independent Gulf League.10 By year’s end Shreve’s services were the property of the Baltimore Orioles of the major-league American Association.11

Shreve was joining a bad club, one coming off a 48-83 last-place finish and in desperate need of improvement in pitching and almost every other department. Yet manager Billy Barnie was reluctant to give his new hurling recruit a chance to show his stuff. Young, privileged, and brash by nature, Shreve did not suffer his disuse in silence. He loudly demanded that the club “give him a chance.”12 On May 2, 1887, Lev got his wish, making his major-league debut in a start against the New York Mets. While something less than an artistic success – Shreve allowed 18 base hits, walked eight, and threw two wild pitches – he nevertheless staggered to a 15-9 triumph. It would be another five weeks before Barnie handed him the ball again. The result was a much tidier 14-5 win over Cleveland. Four days thereafter, Shreve tossed perhaps the finest game of his career, a five-hit, 7-0 whitewash of Cleveland. But after pitching an 8-8 tie game against St. Louis on June 16, Shreve sat idle for another five weeks before dropping a respectable 4-2 decision to Cleveland.

Amid rumors that his effectiveness was hampered by an excessive cigarette-smoking habit, Shreve was released by Baltimore in early August.13 Several days later he signed with the National League Indianapolis Hoosiers, rejoining former batterymate Arundel.14 Shreve was wild in his initial start for the Hoosiers, walking six in his first two innings’ work, but settled down to complete a five-hit, 4-1 victory over Detroit in 10 innings. Lev then assumed a place in the Indianapolis rotation, posting a 5-9 (.357) record that was a modest improvement over the 37-89 (.294) overall log of the last-place Hoosiers.

The relative standings of pitcher and club reversed themselves in 1888. The Hoosiers were slightly improved, with a 50-85 (.370) record good for seventh place. But Shreve’s performance deteriorated, reducing him to one of the worst starting pitchers in the National League. His 11-24 (.314) record was lousy, and he led the league’s hurlers in earned runs (153) and home runs (23) surrendered. There was also a report that Shreve “seemed out of condition” toward season’s end, sportswriter code for overindulging in alcohol.15

Shreve returned to Indianapolis for the 1889 season, but his status with the club was shaky as the campaign opened. On May 6 he pitched decently until undone by a two-run rally in the bottom of the ninth inning, dropping a 7-6 decision to the Pittsburgh Alleghenies. Shortly thereafter, Shreve was released by Indianapolis. Without major-league suitors, Shreve subsequently signed with the Detroit Wolverines of the International Association.16 There, Lev’s pitching staged an unexpected revival. Over the next several months he posted an 18-9 mark for the pennant-winning (72-39) Wolverines. Although pitching mate Edgar Smith’s 18-8 record was fractionally better, the venerable Henry Chadwick deemed Shreve to have achieved the International League’s “best pitching record taking all parts of play into consideration.”17 In mid-August, however, Shreve’s throwing hand was injured when it was struck by an errant pitch while he was batting.18 And when the injury seemed to deprive Shreve of his drop ball, the Wolverines released him.19 In its post-mortem, Sporting Life intoned, “Shreve will leave Detroit with the very best wishes of the patrons. He has always conducted himself in a gentlemanly manner, and gave his best service when most needed.”20

While perhaps heartless, the release afforded Shreve the benefit of a final shot at the majors. Soon after he was let go, Lev signed with Indianapolis for the remainder of the 1889 season.21 But he was shelled in two late-season appearances, including a September 27 outing against Boston in which he was knocked out in the second inning. Shreve finished his bifurcated season with the Hoosiers at 0-3, with an elephantine 13.79 ERA. Indianapolis released him for good shortly after the 1889 season closed.22

Although he would persevere as a minor league and semipro pitcher, the major-league career of Lev Shreve had run its course. In three seasons, he had posted a 19-37 (.339) record, completing 53 of his 57 starts while posting a swollen 4.89 ERA. In 473⅓ innings pitched, he had allowed 551 base hits, yielding a far-too-generous .313 batting average to enemy hitters. Control had also been a problem, with his combined walks/HBP/wild pitches total (243) far exceeding his strikeouts (141). In sum, Shreve, handicapped by a lack of speed and with a pitching repertoire largely confined to a drop ball, had been a less-than-mediocre hurler. But unlike a multitude of minor-league hopefuls, he had nevertheless achieved big-league player status.

Still only 24 years old, Shreve endeavored to continue pitching. Although unattached, he prepared for the coming season with a self-financed sojourn to the restorative spas at Hot Springs, Virginia. There, it was reported that “Shreve is in good form and seems to be very fast. He has acquired a good straight slow ball, something new, but has not entered into a contract yet, as he awaits his price.”23 Obtaining his price was a familiar issue with Lev. Whether a matter of principle or personal pride, Shreve always demanded what he thought his services were worth, however inflated such notions might be. And because he was wealthy – in 1887 Sporting Life had estimated Shreve’s personal net worth at $75,000, well above the value of most major-league franchises24 – and not dependent on baseball for income, he regularly turned down contract offers not to his satisfaction. As the 1890 season began, reports that Shreve was about to sign with Philadelphia Quakers manager Harry Wright foundered on contract terms.25 But subsequently Lev reached agreement with the Minneapolis Millers of the Western Association, informing Sporting Life that he “had set my price and I got it.”26 Six weeks later, Shreve was released. He had not “lived up to management expectations, his drop ball being an easy mark for opposing batsmen,” declared the Omaha World-Herald.27 The Sporting Life assessment focused on different but chronic Shreve shortcomings: a lack of pitching stamina and the absence of variety in his pitching arsenal. Shreve had “pitched good ball” for Minneapolis, but “seemed to tire out after two or three innings,” the baseball weekly observed.28 Thereafter, he auditioned for the rival St. Paul Saints, but quickly drew his release there, as well.29 For his part, Shreve maintained that his releases had been matters of club economy, not performance deficiency on his part, and available Western Association stats lend this claim some credence. In 11 games combined between the two clubs, he posted a creditable 1.90 ERA.30 From that point, Shreve sat out the remainder of the 1890 season, declining “several offers.”31

Shreve began his final season in Organized Baseball as a member of the Rochester Hop Bitters of the Eastern Association. He “pitched poor ball” in his Rochester debut, a 6-5 loss to Buffalo in 10 innings.32 He was then “so badly injured in practice … that he had to be taken to the hospital for treatment.”33 Upon his return, Shreve pitched well but without much luck, going 6-7 despite a sparkling 1.39 ERA. The end of his Rochester tenure was apparently prompted by conduct at a June 24 doubleheader against New Haven. Intoxicated, Shreve and shortstop Pete Sweeney arrived at the ballpark “in no condition to play ball,” and were promptly fined $50 apiece for “over-indulgence” by the club directors.34 Shortly thereafter, Rochester gave Shreve his release.35

Still only 26, Shreve returned to Hot Springs the following spring “for a ten-weeks scour, and will be in pitching order by April 15.”36 But he received no professional call for his services, Instead, he played some outfield for the Deepens, the Kentucky semipro champions for the next two seasons. Lev remained bent on a comeback, but reportedly rejected a contract offer from an unidentified Southern League club in April 1893, preferring to hold out for a major-league offer instead.37 That offer never came, bringing Shreve’s ballplaying days to a close well before he had reached age 30.

Given the influence of the Shreve family, Lev was soon on the Louisville municipal payroll “at a good salary.”38 In early 1897 Shreve returned to Detroit, where he pronounced his pitching arm in shape and asked the Western League Detroit Tigers for a tryout.39 But this was just a lark, as Lev had not left Louisville for baseball purposes. Rather, he was preparing to alter his domestic situation by marrying Elizabeth Mitchell. After the ceremony, the couple settled in Detroit, where their only child, son Charles Upton Shreve III, was born in March 1898.

Lev Shreve spent the remainder of his life out of the limelight. According to the 1900 US Census, he was then employed as a supervisor at a Detroit electric plating plant. He later moved on to the Ford Motor Company, where he assumed an executive position. During this time, Shreve lived at various Detroit addresses until 1927, when the he and his wife relocated to a Tudor-style mansion in the tony suburb of Grosse Pointe. By this time, it appears that Shreve had retired from Ford and had assumed his late father’s post as manager of the Shreve family estates.40 On November 7, 1942, Leven Laurence Shreve II died at his home.41 He was 76. Following funeral services, his remains were interred in the Shreve family plot in Cave Hill Cemetery, Louisville. Survivors included his wife, Elizabeth; son Charles Upton Shreve III; and older brother Charles Upton Shreve Jr.

Sources

The primary source for the Shreve family history info recited herein is Luther Prentice Allen, The Genealogy and History of the Shreve Family from 1641 (Greenfield, Illinois: privately published, 1901), an authoritative 650-page treatise commissioned and reviewed for accuracy by family members, including Lev’s father, Charles Upton Shreve. Other sources include US Census reports, Shreve family posts on Ancestry.com, and certain of the newspaper articles cited below. The source for baseball-related commentary is specified in the endnotes. Unless otherwise stated, stats have been taken from Baseball-Reference.

Notes

1 The Shreves were descendants of seventeenth-century English Dissenters. The surname Shreve is derived from the Middle English word for sheriff.

2 The history of the Shreve family is exceptionally well-documented. The definitive study is Luther Prentice Allen, The Genealogy and History of the Shreve Family from 1641 (Greenfield, Illinois: privately published, 1901), a detailed and exhaustive accounting commissioned by the family. A primary financier of the work was Lev’s father, Charles Upton Shreve. The Shreve family history in general, and Lev Shreve’s birth name and birth date in particular, are also chronicled in Ida Morrison Shirk, Descendants of Richard and Elizabeth (Ewen) Talbott of Poplar Knowle of West River, Anne Arundel County (Clearfield, Pennsylvania: Day Printing Company, 1927), and Pioneer Families of Jessamine County, Kentucky (Jessamine County Historical Society, publication date unknown). All three of these works can be accessed online.

3 Lev Shreve’s headstone at Cave Hill Cemetery in Louisville gives his date of birth as March 12, 1865. Note further that the biographical data for Lev Shreve published in Baseball-Reference, Retrosheet, and other modern baseball reference works are almost entirely wrong, likely the legacy of a surprisingly error-filled player questionnaire completed by his son, Charles Upton Shreve III, in December 1968. Efforts to correct the baseball reference listings for Shreve were ongoing at the time this bio was published.

4 Lev’s middle name was frequently misspelled Lawrence. His middle name Laurence was derived from the maiden name of namesake Leven Laurence Shreve’s mother, Mary Elizabeth Laurence.

5 His older siblings were Sallie (born 1852), Eliza (1854), Thomas (1855), Evalena (1858), Minnie (1860), and Charles Upton Shreve Jr. (1863).

6 According to the Lev Shreve player questionnaire completed by his son. The 1940 US Census also credits Lev with three years of college.

7 To disguise his identity, Lev “may have used the name Sam Shreve or some other name” early in his playing days. Letter of Colonel Charles Upton Shreve (III) to Joseph E. Simenic, dated December 15, 1968, contained in the Lev Shreve file at the Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York.

8 Apart from the surname “Shreve,” no identifying info is provided in Sporting Life, April 15, 1885.

9 As reported in the Macon (Georgia) Telegraph, July 8, 1886, and Sporting Life, July 14, 1886.

10 Baseball-Reference also lists the Eau Claire (Wisconsin) Lumberjacks of the Northwestern League as on Shreve’s 1886 itinerary, but the writer found no evidence of same.

11 See Official Bulletin No. 10, published in Sporting Life, November 13, 1886.

12 See the Baltimore Sun, May 9, 1887.

13 According to “There Was Probably None So Unique as Shreve,” Baseball History Daily, July 24, 2013, citing reports that Shreve and fellow rookie hurler Ed Knouff were labeled “cigarette fiends.” The Baltimore Sun, August 3, 1887, merely reported that Shreve was released because “he was not thought capable of doing the work required of him” by manager Barnie. This despite Shreve’s 3-1 record in five games for the Orioles. Knouff, meanwhile, was released to St. Louis.

14 As reported in the Baltimore Sun, August 9, 1887.

15 Indianapolis correspondent A.G. Ovens in Sporting Life, October 3, 1888.

16 As reported in the Boston Herald, Philadelphia Inquirer, and Wheeling (West Virginia) Register, May 18, 1889.

17 Sporting Life, January 8, 1890.

18 As reported in the Boston Herald, August 14, 1889.

19 See Sporting Life, October 9, 1889.

20 Sporting Life, September 25, 1889.

21 As per the Saginaw (Michigan) News, September 25, 1889.

22 As reported in the Philadelphia Inquirer, October 11, 1889.

23 Sporting Life, April 2, 1890.

24 See Sporting Life, September 10, 1887. Lev’s personal fortune, however, was little more than a pittance by Shreve family standards. Father Charles Upton Shreve, for example, was well-to-do in his own right before inheriting $1.5 million from his own father in 1869.

25 See the Philadelphia Inquirer, April 23, 1890, and Omaha World-Herald, May 4, 1890.

26 Sporting Life, May 31, 1890.

27 Omaha World-Herald, July 6, 1890. Another Midwestern daily added, “His curves were too straight for hitters in the Western Association.” See the (Lincoln) Nebraska State Journal, July 3, 1890.

28 Sporting Life, June 7, 1890.

29 As reported in Sporting Life, July 19, 1890.

30 According to official Western Association stats published in the Chicago Inter-Ocean, October 19, 1890. No won-lost record was provided for WA pitchers in the published stats. Baseball-Reference has no statistical data whatever for Shreve’s 1890 season.

31 As per Sporting Life, August 10, 1890.

32 In the estimation of an unidentified Sporting Life correspondent, May 23, 1891.

33 Sporting Life, May 30, 1891.

34 As reported in Sporting Life, July 11, 1891.

35 As per Sporting Life, August 1, 1891, which added that Shreve had pitched winning ball for Rochester, but “for some reason he was hardly ever in shape to take his regular turn in the box.”

36 As per Sporting Life, March 12, 1892.

37 As per Sporting Life, April 1, 1893.

38 As reported by the Boston Herald, August 7, 1896, and Sporting Life, August 15, 1896.

39 According to Sporting Life, May 2, 1897.

40 As per the 1920 US Census and the posthumous player questionnaire completed by Lev’s son in December 1968.

41 As reported in the death notices printed in the Detroit Free Press and Detroit News, November 8, 1942, and the obituaries published in the Grosse Pointe (Michigan) Review, November 12, 1942, and Grosse Pointe News, November 19, 1942. No cause of death was published at the time, but the 1968 questionnaire completed by Charles Upton Shreve III stated that his father died from “age.”

Full Name

Leven Laurence Shreve

Born

March 12, 1866 at Louisville, KY (USA)

Died

November 7, 1942 at Grosse Pointe, MI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.