Pop Corkhill

It’s unlikely that Pop Corkhill is discussed as an outfielder on par with Mays, Mantle, and Musial. Perhaps he should be.

It’s unlikely that Pop Corkhill is discussed as an outfielder on par with Mays, Mantle, and Musial. Perhaps he should be.

During his major-league career — from 1883 to 1892 — Corkhill placed in the top 10 for fielding percentage eight times; range factor seven times; assists five times; and putouts four times.1

For his time, Corkhill was a defensive template. Worthy of Cooperstown? As of the writing of this article in 2019, Corkhill’s name is not commonly argued for Hall consideration; his career batting average was .254. But the evolution of scholarship regarding the deadball era yields more attention on Corkhill’s fielding artistry, ability, and achievements.

With an impressive career fielding percentage of .947, he had twice as many career putouts as games played — 2,156 and 1,041.2 “What a fellow Corkhill was on those forward running catches! He could skate in on his breastbone and snatch flies off the grass,” recalled Sporting Life writer Ren Mulford, Jr. in 1907, some 15 years after Corkhill’s retirement.3

During a Philadelphia-to-Denver trip that year, Corkhill stopped in Cincinnati and spent some time with Mulford, who was complimentary in his account of the conversation with “the greatest man that ever came in from the field and slid for flies.” Neither cocky nor arrogant, but perhaps a bit biased, Corkhill assessed his measure as an excellent fielder with few parallels in the present game. “Of course, the games are interesting, but I don’t think the players to-day are as aggressive or carry as many of the scars of war that we did.”4

John Stewart Corkhill was a native of southeastern Pennsylvania, born on April 11, 1858 about 50 miles from Philadelphia in Parkesburg, a borough with a genesis dating back to the 1730s, when it began as the Fountain Inn. As of the writing of this article, that structure is a private home.5 Corkhill didn’t move too far from his roots — at 18, he pitched for an amateur Philadelphia team called Our Boys. In 1879, he broke through the professional ranks by manning second base with the Philadelphia Pearls, an independent team.6

Marriage beckoned for the ascending ballplayer; on November 20, 1881, Corkhill married Martha Jackson.7 Tragedy followed when their baby was born on June 5, 1882, but only lived six hours before expiring. The baby was named John, too.8 It was fortuitous, or perhaps intentional, that Corkhill stayed around Martha and the City of Brotherly Love; he played first base for the Philadelphia ball club in the National League’s League Alliance in 1882. His “great proficiency” caught the attention of the American Association’s Baltimore Orioles but Corkhill went west instead of south when the Cincinnati Reds — the 1882 American Association champions — launched his major-league career the following season.9 The cost of buying Corkhill’s contract was an estimated $400.10

Corkhill played in 88 games in 1883 — he ended the season with a .216 batting average and 81 hits, including 10 doubles and eight triples. His playing time increased in 1884, as did his offensive output: .274 batting average and 124 hits, including 13 doubles and 11 triples.

By 1885, it was clear that Corkhill’s presence on the Cincinnati squad was a given. He led the American Association with 112 games played and found even more playing time in 1886 with 129 games played, plus a .265 batting average, and 97 RBI. Corkhill matched his RBI total in 1887.

While better known for his fielding exploits, Corkhill was a pioneer of sorts on the base paths. An entry in the April 30, 1887 edition of the Dayton Herald highlighted his approach to sliding head first, earning him the distinction of being the sole veteran player to adopt this base running strategy.11

During his time in Cincinnati, Corkhill also contributed to the pitching staff; he took the mound 17 times and compiled a 3-4 record with one game saved. In 1885, he led the major leagues with seven finished games.

Towards the end of the 1888 season, Cincinnati bid goodbye to the stellar fielder after 118 games and the team’s 8-4 error-filled loss to Brooklyn, soon to be Corkhill’s new team. The Cincinnati Enquirer noted that Corkhill’s performance as “not up to a winning standard,12 but the Brooklyn Daily Eagle cited a dispatch calling Corkhill a “fine base runner.”13

The Bridegrooms — a tag preceding the Brooklyn team’s Trolley Dodgers, Robins, and Dodgers labels — handed over $3,500 to Reds owner Aaron Stern for Corkhill.14 It was a price gladly met by team owner Charles Byrne: “You know by this time I secured John Corkhill from Cincinnati. I wanted him a year ago and would have had him but for Mr. Stern’s breaking faith with me.”15

It is unfair to credit Byrne’s business savvy for Cincinnati’s release, though. Getting rid of Corkhill was a symbol of the friction between the players and Stern, emphasized by a quarrel over a $50 fine when Corkhill missed a game against the Kansas City Cowboys. His replacement, Jack O’Connor, fell short both in the field and at the plate. Corkhill’s first-rate performance the next day — two hits, two runs scored — did not change Stern, who already felt disrespected by his squad16 and clarified his position with “a firmness that could not be mistaken.”17

Corkhill finished out the 1888 season in Brooklyn, playing in 19 games with a .380 batting average. Combining his Cincinnati stats produced a .285 average for the year. His manner induced the Daily Eagle to advocate for Corkhill to become captain: “He has thorough control of temper, is the ablest and most experienced player in the team, and he is a team worker in every respect, a man who will command the respect of the town.”18

Recognizing authenticity is a Brooklyn trait. It’s probably in the DNA. Indeed, reverence for Corkhill was hardly steeped in idolatry; the Brooklyn crowd found him to be a fixture on a successful ball club, met with open arms after his transfer from Cincinnati. An opposing player was an enemy — but a Brooklyn uniform earned treatment like he was born and raised in Flatbush, no matter his city of origin. In 1889, Corkhill set a personal record by playing in 138 games; his average was .250. Again, the Daily Eagle praised him: “It would be impossible to describe the high regard in which Pop Corkhill is held by the Brooklyn patrons of the game. He is looked upon as a thorough gentleman and his every act meets with big applause.”19

In the World Series against the New York Giants, Corkhill left Game One in the fourth inning after catching a “long fly” from Giants second baseman Danny Richardson followed by a “complete somersault.”20 After the series, it was reported that “an abscess has developed on the lower part of his spine, and it may occasion serious trouble.”21 Corkhill batted .208 in the series; the Giants won the best-of-11 format 6-3. A New-York Tribune retrospective of the teams a few days after the series underscored Corkhill’s prowess in the field: “He is supposed to cover only centre [sic] field for the Brooklyn club, but in reality covers an immense amount of territory in a game.”22

A couple of months later, the Bridegrooms released him, “owing to his inability to recover the use of his throwing arm.”23 Popularity mattered not. The Daily Eagle suggested that Corkhill look towards umpiring as job because his “period of usefulness on the diamond appears to be over.”24 The New York Evening World described the feeling around Washington Park as “gloom” upon Corkhill’s departure.25 There were no more games played in the 1890 season for the 32-year-old Corkhill, who ended his season with 51 games played and a .225 average.26

In 1891, he played on three rosters — Philadelphia for 83 games, Cincinnati for one game, and Pittsburgh for 41 games. A combination of stats from the three tenures resulted in another weak average of .213. Late in the season, Corkhill got smacked in the jaw by an Ed Crane pitch during a Pirates-Reds game. The Pittsburgh Dispatch described Crane’s throw as “an ugly one.”27 The Pirates lost the game 7-6. There were three games left in the season, but Corkhill was not to play in them.28

Corkhill wrapped up his major-league career with Pittsburgh in 1892, playing in 68 games and dropping below the .200 average for the first time in his career — .184. In mid-September, 1892, he announced that he would leave baseball for good.29 His .254 career batting average encompassed 1,120 hits.

In this last season, Corkhill showed flashes of brilliance, proving wrong those doubters who believed that he had lost his effectiveness later in his career. During a 6-4 loss in April to the Louisville Colonels, Corkhill made “a most remarkable running catch.”30 Approximately 1,500 fans braved a drizzling May afternoon to see Corkhill prevent the opposition from gaining an offensive foothold: “His game was of the highly sensational kind, cutting off at least three three-baggers.”31 It wasn’t enough — Cleveland won 6-1. Corkhill knocked in Pittsburgh’s lonely run.

Corkhill’s physique and visage conveyed authority, which led to a humorous assumption of his identity on a train during his tenure in Cincinnati because of a frock coat that gave him the appearance of an evangelist when “buttoned tightly to the chin.” A passenger mistook Corkhill for the religious type when a certain evangelist was expected to board the train at the same time as the Cincinnati squad during a road trip. Corkhill, in turn, mistook the passenger as a fan when he praised Corkhill and asked if he “missed” saving a person. “Miss? I missed one on that thick-headed, brawling, kicking, nagging, Irishman, Tebeau, just back of second, the first time I’ve missed one in three seasons, and of all the d — d men I ever missed on, I’d rather it would have been any cuss on earth than him,” responded the ballplayer.32

Mistaken identity has rarely been funnier.

Corkhill places in the top 10 outfielders for Stat Geek Baseball, a web site that breaks down baseball statistics.33 “The analysis of a defensive standpoint paradigm ranks from average to maximum for every year,” explains Jeff Peterman, Stat Geek Baseball’s president. “It’s not a composite because every year is graded individually on four components — fielding percentage, assists per game, durability based on games played, and range factor (how many plays that turn into outs per game). The maximum defensive value for an outfielder is 1.7 for a year. Corkhill was 1.5927 for his career. If you look at baseball-reference.com, his WAR factor is 2.3 for his career with a total offensive value of 5.1. So, nearly half of his value is defense. It may be a little high, but Corkhill doesn’t get a high offensive rating on our scale.”34

After leaving the baseball diamond, Corkhill stayed active in his community as a civil servant and a businessman. In 1896, Corkhill got the job of Chief of Police of Stockton, New Jersey. He also ran a grocery business35 and opened a second-hand furniture store in Philadelphia.36 There was another furniture store added to his portfolio soon after;37 for the 1900 U.S. Census, Corkhill put furniture salesman as his occupation.38 Ten years later, the 1910 Census listed his occupation as Storage Business.39

In 1921, Pop Corkhill died at home after an operation. His obituary highlighted the achievement of not dropping a fly ball for three years in a row.40 Martha Corkhill passed away in 1949.41

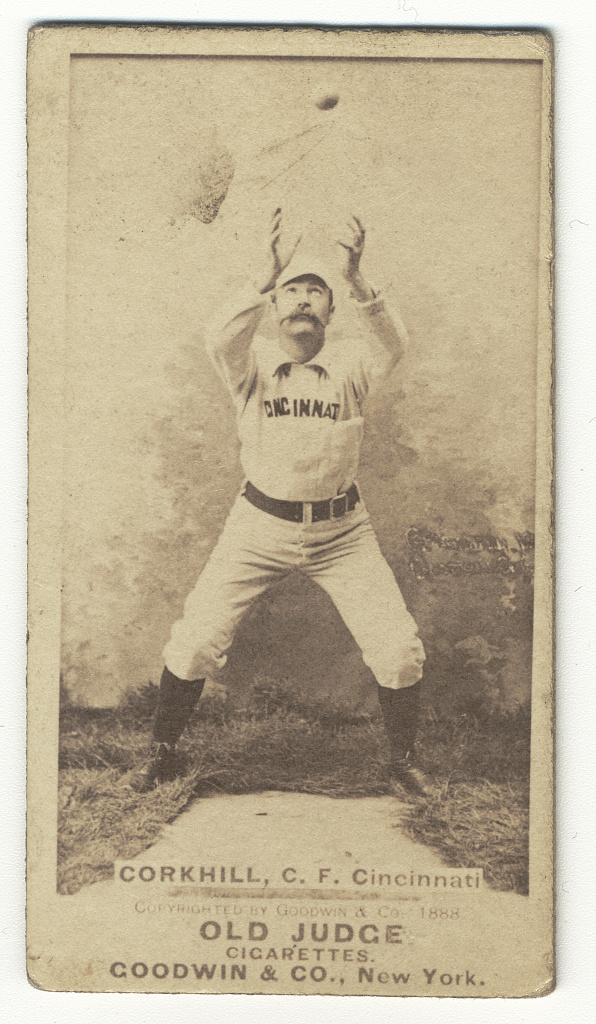

An Old Judge Cigarettes baseball card shows Corkhill in his Cincinnati uniform, looking towards a falling ball with his arms outstretched preparing to catch it. The image captures the essence of one of the best — if not one of the best known — outfielders to play the game.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Darrell Jarvis and verified for accuracy by the BioProject fact-checking team.

Notes

1 Pop Corkhill: Standard Fielding, Baseball Reference, https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/c/corkhpo01-field.shtml

2 Ibid.

3 Ren Mulford, Jr., “The Era Of Experiment In Good Old Cincinnati,” Sporting Life, February 2, 1907.

4 Ren Mulford, Jr., “Fighting Reds,” Sporting Life, July 13, 1907.

5 “A Brief History of Parkesburg,” http://www.parkesburg.org/index.aspx?NID=865.

6 David Nemec, ed. Major League Baseball Profiles: 1871-1900, Volume 1, The Ballplayers Who Built the Game (Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 2011) 522.

7 John S. Corkhill, https://www.ancestry.com/family-tree/person/tree/1569692/person/1652882136/facts?ssrc=

8 John Stewart Corkhill in the Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Death Certificates Index, 1803-1915, https://search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?indiv=1&dbid=2535&h=2178400&tid=&pid=&usePUB=true&_phsrc=NVm4&_phstart=successSource.

9 “John S. Corkhill,” The Brooklyn Baseball Club: Official Score Book, Season of 1890. “The League Alliance arose as the National League of Professional Base Ball Clubs’ response to the perceived threat of the International Association of Professional Base Ball Players in 1877. Having subverted the National Association of Professional Base Ball Players, plucking St. Louis, Hartford, Boston, the Mutuals of New York and the Athletics of Philadelphia from its ranks and adding independent teams from Louisville and Cincinnati, Chicago president William A. Hulbert sought to extend the League’s powers to independent teams across the country, limiting the availability of players while protecting the sanctity of contracts.” Brock Helander, “The League Alliance,” SABR Baseball Biography Project, https://sabr.org/bioproj/topic/league-alliance.

10 Nemec, Major League Baesball Profiles: 1871-1900, Volume 1, The Ballplayers Who Built the Game, 522.

11 “Baseball,” Dayton Herald, April 30, 1887: 5.

12 “Bad Fielding: Causes the Reds to Lose a Game, John Corkhill Released to the Brooklyn Club,” Cincinnati Enquirer, September 24, 1888: 2.

13 “A New Player,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 24, 1888: 1.

14 “Latest News Items,” Coshocton Tribune, September 25, 1888: 2.

15 “Still A Chance: For Brooklyn to Capture the Pennant. President Byrne, However, Seems to Have No Hope and is Wasting No Time in Useless Regrets,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 29, 1888: 6.

16 “The Release of Corkhill,” New York Sun, September 25, 1888: 3.

17 Ibid.

18 “Talking Of Next Season,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 2, 1888: 14.

19 “Costly Errors,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 12, 1889: 2.

20 “One Game For Brooklyn,” New York Times, October 19, 1889: 3.

21 “The Fight Over,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, October 30, 1889: 1.

22 “Brooklyn’s Pet Players,” New-York Tribune, November 3, 1889: 18.

23 “Keeping It Up,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 5, 1890: 1.

24 Ibid.

25 “Gloom Across the Bridge Since ‘Pop’ Corkhill’s Release,” New York Evening World, August 6, 1890: 1.

26 “League Notes,” Boston Globe, July 12, 1890: 5.

27 “They Win Another,” Pittsburgh Dispatch, September 30, 1891: 8.

28 “The National Game,” Pittsburgh Press, October 1, 1891: 5.

29 “Sporting Notes,” Akron Beacon Journal, September 13, 1892: 3.

30 “Ehret, The Erratic,” Pittsburgh Dispatch, April 28 1892: 8.

31 “Beaten At Cleveland,” Pittsburgh Daily Post, May 14, 1892: 6.

33 http://statgeekbaseball.com/fieldingcbest_of.html

34 Telephone interview with Jeff Peterman, November 6, 2018. Corkhill’s Top 10 ranking is based on analysis of players as of 2017.

35 “Not Much Interest In The Big Fights,” Philadelphia Inquirer, February 2, 1896: 8.

36 “Sporting Notes,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 10, 1893: 8.

37 “Base Ball Notes,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 13, 1895: 8.

38 1900 United States Census, https://www.ancestry.com.

39 1910 U.S. Census, https://www.ancestry.com.

40 “Corkhill Is Dead,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 7, 1921: 15.

41 “Mrs. Martha C. Corkhill,” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 9, 1949: 12.

Full Name

John Stewart Corkhill

Born

April 11, 1858 at Parkesburg, PA (USA)

Died

April 3, 1921 at Pennsauken, NJ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.