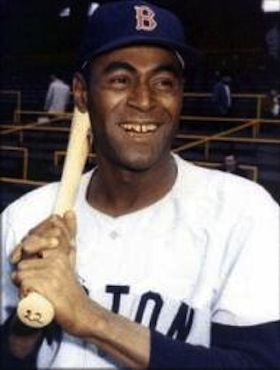

Billy Harrell

On June 14, 1952, Billy Harrell signed a contract with the Cleveland Indians which began a 15-year professional baseball odyssey. Across this career, he appeared in 153 major league games (136 with Cleveland and 37 with the Boston Red Sox) and 1520 minor league games with eight different teams. While his big league stats were modest, a .231 lifetime batting average with eight home runs and 26 RBIs, Harrell’s minor league batting average was a healthy .284, with 114 home runs and 573 RBIs. Described by Kirby Farrell, his manager at Cleveland and several minor league stops, as having, “such tremendous hands, he could play the infield without a glove,”1 Harrell played every position except catcher over the course of his career, even serving occasionally as a mop-up pitcher.

On June 14, 1952, Billy Harrell signed a contract with the Cleveland Indians which began a 15-year professional baseball odyssey. Across this career, he appeared in 153 major league games (136 with Cleveland and 37 with the Boston Red Sox) and 1520 minor league games with eight different teams. While his big league stats were modest, a .231 lifetime batting average with eight home runs and 26 RBIs, Harrell’s minor league batting average was a healthy .284, with 114 home runs and 573 RBIs. Described by Kirby Farrell, his manager at Cleveland and several minor league stops, as having, “such tremendous hands, he could play the infield without a glove,”1 Harrell played every position except catcher over the course of his career, even serving occasionally as a mop-up pitcher.

Born on July 18, 1928, in Norristown, Pennsylvania, to John Nurney Harrell and Queen Ethel Harrell, William Harrell was the youngest in the family of five boys and one girl. When Harrell was a year old his father moved the family to Troy, New York, to take a job working in a coke plant.

An outstanding athlete at Troy High School, Harrell starred in both basketball and baseball. In the latter sport, he was selected to play in the annual Hearst Sandlot Classic in both 1946 and 1947. Played in the Polo Grounds in New York, the Hearst Classic showcased nationally selected amateur talent and attracted many major league scouts. He was the first African-American invited to play in the Classic and, in his study of these games, Alan Cohen observes, “Harrell’s appearance was even more historic in that, when he played in the Hearst Classic for the first time, Major League Baseball was not integrated.”2

After high school, Harrell received a basketball scholarship to Siena University in nearby Loudonville. During the three years that Harrell was eligible for varsity play Siena compiled a 70-19 record. Siena coach Danny Cunha called Harrell, “the most graceful, most coordinated player I have ever seen on a basketball court.”3

Harrell also starred in baseball at Siena, batting over .400 in both his sophomore and junior seasons. Since he played shortstop with the Birmingham Black Barons of the Negro American League during the summer of 1951, he was not eligible for Siena baseball his senior year.

A busy 1952 began for Harrell with his marriage to Vivian Agana, as well as his graduation from Siena. He then declined opportunities to play with the Harlem Globetrotters as well as the NBA’s Indianapolis Olympians, instead signing as an amateur free agent with the Cleveland Indians on June 14.

Assigned to the Reading Indians of the Class A Eastern League, Harrell started in the outfield for a week. Then, a casualty of a crowded Reading roster, he was re-assigned to Cedar Rapids, in the Class B Three-I League. Unhappy with the re-assignment, Harrell jumped the team and went home to Troy, recalling that “I didn’t really want to go. My wife was pregnant, and I was going all the way out to Iowa.”4 Harrell’s father convinced him to rejoin the team, taking a day off from work to take him to the train. Harrell explained, with a laugh, “He wanted to make sure I went back.”5 At Cedar Rapids, Harrell hit .325 in 55 games.

A 1952 Ebony Magazine article titled “Future Jackie Robinsons: Amateur Teams Will Supply Major Leagues with New Crop of Negro Stars,” featured Harrell along with several other future major leaguers, including Earl Wilson.6 Although the article appeared five years after Robinson had broken the color line, the “Future Jackie Robinsons” would face a number of challenges, as in 1952 racial equality in organized baseball was far from a reality. Underscoring this fact was that five years after Robinson’s debut, more than half of all major league teams were still all-white.7

Harrell’s first encounter with racial discrimination occurred a few years earlier at a restaurant in Washington when he sat down to eat with his Siena teammates, but was refused service because he was black. He recalled with pride that his teammates all immediately walked out of the restaurant, adding he was “shocked” as, “I had spent most of my life in Troy, and never had anything like this happen. What really got me was that this was occurring in our nation’s capital, of all places.”8 A couple years later, with the Birmingham Black Barons, he saw a sign for “colored” water fountains for the first time, and could not immediately process the prejudice, “the first thing I thought of is if they had ‘colored water.’”9

By the time Harrell signed with Cleveland, he was more familiar with, if no less angered by, what he experienced. Prior to the Indians shifting their training site to Arizona, Harrell joined the team for their 1953 spring training in the South. “We took a lot of crap. Rocky Colavito and Herb Score had to get my food and bring it back on the bus.”10 Racist comments poured down from the stands on occasion, but Harrell recalled, “I just ignored it and tried to hit the ball. The guys on the team were behind me 100 per cent. You get base hits and that’s what I did.”11

A major incident occurred later in the same spring training when a team of Cleveland minor leaguers travelled to Winter Garden, Florida, to play an exhibition game. Harrell and teammate Brooks Lawrence were barred from playing by a city ordinance permitting only white players to play. Outraged at the incident, Indians General Manager Hank Greenberg issued a public statement that “In the future if our Negro boys are not accepted, there will be no game.”12

Back with the Reading Indians for the 1953 season, Harrell hit .330, added 84 RBIs, and was named the Eastern League’s Most Valuable Player. After starting the season in the outfield, Harrell moved to shortstop, and was named to the league All-Star Team as a ‘utility player.’

The 1953 Reading team won an Eastern League record 101 games. On the team with Harrell, were 11 other future major leaguers, including Brooks Lawrence, Rocky Colavito, Herb Score, Bud Daley, Joe Altobelli, and Gordie Coleman. Manager Kirby Farrell would go on to manage Cleveland in 1957. “When I won the MVP award the fellas on the team really congratulated me,” Harrell said of his Reading teammates, “No jealousy. It was a great group.”13

Promoted to the Indianapolis Indians of the Class AAA American Association in 1954, Harrell batted .307. In the field, he played 87 games at third base, 22 games at shortstop, and 31 in the outfield. Under manager Farrell (also promoted from Reading) the team won the regular-season pennant as well as the league championship.

At Cleveland’s 1955 spring training Indians manager Al Lopez saw in Harrell, “great possibilities as a shortstop.”14 Yet, sticking with the experienced but light-hitting George Strickland at the position, Lopez decided to send Harrell back to Indianapolis. But the Cleveland skipper recommended he be used at shortstop there to gain confidence and experience in the position as, “he has everything–speed, a fine arm, agility, good hands and he swings a strong bat.”15

Again playing for Farrell, Harrell batted .274, drove in 60 runs, and earned a spot as a shortstop on the league All-Star Team. Besides appearing in 109 games at shortstop, Harrell appeared in 32 games in the outfield, and 16 at third base.

On September 1, with Cleveland a half-game behind the first-place White Sox, and with Strickland’s average dipping to .211, Harrell was promoted to the Indians. Overwhelmed as he entered Cleveland Stadium for the first time for a September 2 game against the White Sox in front of 24,383 fans, Harrell recalled how, “I just said to myself, ‘You gotta be kidding me.’” Harrell remembered his first major league at-bat with a laugh, “I was sitting on the bench when Lopez called on me to pinch hit. Except Lopez [was] calling, ‘Farrell’ and I’m not paying any attention. I still hear, ‘Farrell, Farrell.’ So then [my teammates] said, ‘Hey Billy, that’s you.’ So I went up to hit. After two strikes and butterflies I hit the ball, but it went right back [to pitcher Jack Harshman], an ‘at ‘em’ ball.”16

For the rest of September, Harrell appeared in 13 games, batting .421 in 22 plate appearances, and started at shortstop in four of the final five games. Assigned to room with future Hall of Famer Larry Doby, Harrell described how, “He always would tell me, ‘Keep yourself going. Keep running.’”17 Harrell credited Doby with influencing him more than anyone else in his career.

Coming off the stellar September, Harrell “had my hopes up” for the next season.18 However, in late October the Indians traded Doby to the White Sox for veteran shortstop Chico Carrasquel–an All-Star in four of the previous five seasons. Explaining the move, Al Lopez stated, “We needed a bat at short.”19 Asked about Harrell’s chances at shortstop, Lopez said, “We will play him there in the spring and if he can beat out the others the job will be his.”20

But, when Strickland hit .372 during 1956’s spring training, Harrell was again assigned to Indianapolis. Recalling his disappointment, Harrell reasoned, “It’s part of the game, part of the life.”21 Playing for Farrell for the fourth year in a row, Harrell batted .279. Appearing in 33 games at shortstop and 88 games in the outfield, Harrell again earned a spot on the American Association All-Star team as a utility player, but received no late season call up with Cleveland.

After Indianapolis won the regular-season pennant, and league championship, Farrell was promoted to manage Cleveland for the 1957 season. Harrell was one of several players Farrell tried at third base in spring training to fill the gaping hole created by the unexpected retirement of Al Rosen. Harrell impressed the local press as, “absolutely brilliant at third base.”22 However, Farrell openly questioned “whether the rookie would hit enough to hold the job in the big leagues.”23

Although Harrell made the Opening Day roster, he appeared in only 10 games with one hit in 14 plate appearances, before being optioned on May 15 to Cleveland’s new Open Class affiliate, the San Diego Padres of the Pacific Coast League. Despite being unhappy with the demotion, Harrell otherwise enjoyed his time in San Diego and batted .276, playing mostly (108 games) at shortstop. Promoted to the Indians in mid-September, Harrell was immediately inserted in the lineup at shortstop, getting four hits and driving in three runs in his first two games. Batting .310 in 42 plate appearances while playing three infield positions, Harrell made “a solid impression at shortstop during the final weeks of the campaign.”24 The productive September lifted Harrell’s average to .263 for the year.

Yet, after a decade of first-division play, the Indians fell backwards to a 76-77 mark in 1957. In the offseason Farrell was replaced by Bobby Bragan as the Indians’ manager.

Playing for Santurce in Puerto Rican League that winter, Harrell won the league batting championship with a .317 average. Of Harrell’s performance at the plate and in the field, Santurce manager Ramon Concepción, stated simply, “Bob Bragan’s battle for his Cleveland shortstop is over.”25

Going into 1958’s spring training, the 30-year-old Harrell had no options remaining, so the Indians could not assign him again to the minor leagues without putting him through waivers. After a strong spring training start, Harrell slumped, and, when the season began, was assigned to a role as a late-inning defensive replacement for Bobby Avila at third base.

Carrasquel slumped, however, and the ever-versatile Harrell emerged as the regular shortstop that May, making all the plays in the field while hitting around .250. “Harrell’s speed and competitive spirit,” was exemplified by his stealing of home twice earlier in the season, while Cleveland base-running coach Harrison Dillard stated Harrell was the fastest man on the team in circling the bases.26

On June 11, hitting a respectable .268, Harrell pulled a thigh muscle in a game against the Orioles. The next day, Indians General Manager “Trader” Frank Lane sent Carrasquel to Kansas City for Billie Hunter.

With Hunter taking over as the regular shortstop, when Harrell returned to duty on June 22, it was at third base. His batting stroke apparently impaired by the layoff, Harrell went 0-for-11 for the rest of June, and his role was reduced to being a late-inning defensive replacement for Hunter.

On June 26, Bragan was replaced by Joe Gordon, who alternated Hunter at shortstop with rookie Billie Moran for the next month. On July 26, with Moran and Hunter both batting below .200, he reinstated Harrell as the starting shortstop. Harrell responded by getting hits in each of the next four games. But in the second inning of a July 29 match with the Orioles, while beating out an infield hit, he re-aggravated the same leg injury which had sidelined him earlier in the season.

Trying to play through the injury, Harrell slumped severely, with seven hits in 51 at-bats over the rest of the season. The magnitude of the two-month slump was apparent in that all of Harrell’s seven home runs and 19 RBIs that year occurred before July 30. His final average dropped to .218. It was a disappointing ending to a season which had, at earlier junctures, seemed to find Harrell on the edge of a breakthrough.

With Harrell out of options, and Lane not being able to find any takers that offseason, on February 2, 1959, he was claimed by the St. Louis Cardinals, who bought his contract for the waiver price.

Indians beat writer (and future J.G. Taylor Spink Award winner) Hal Lebovitz often recognized Harrell for his adaptability, intelligence, and polite demeanor. And, on a number of occasions, he noted with distress how the Indians had failed to advance Harrell after four seasons of fine AAA performances. Teammate Minnie Minoso thought Harrell never got a fair shot at a starting job, calling him “a good prospect [who] was not given the chance he deserved.”27

Observing Harrell’s disappointment at not breaking through with the Indians, Jim “Mudcat” Grant spoke admiringly of his teammate’s professionalism: “unlike a lot of players where, although they wouldn’t talk about things in public, in private there would have been yelling and screaming … that wasn’t the case with Billy. He kept it to himself.”28

Grant also noted, “If you came to Bill he would always give you good advice–‘cool down’ kind of advice–he was calming.” Harrell also, Grant recalled, assisted a number of young African American teammates deal with the era’s racial discrimination, “Coming out of the East like he did, there was a lot that [Harrell] didn’t understand [about discrimination in the South] but he still was very helpful at times whenever you had a problem and went to him.”29

St. Louis announced that Harrell would be used as a utility infielder and in spring training assigned him to the Rochester Red Wings, the Cardinals AAA affiliate in the International League. With Rochester, Harrell batted .266, splitting his time between shortstop (71 games), third base (51 games), and second base (27 games).

Harrell didn’t make it to the parent club in 1959, but a unique game that July began an incredible sequence of events.

First, on July 25, a day before the sixth anniversary of the onset of the Cuban Revolution, the Red Wings were in Cuba for a game against the Havana Sugar Kings. A suspended game from the night before was completed, then the large crowd was treated to the additional attraction of a few innings of play between army teams, featuring a pitching appearance by Cuba’s new leader, Fidel Castro.

The regularly scheduled game thus started late, and it was close to midnight when Harrell hit a home run in the top of the eleventh inning to give the Red Wings the lead. The Sugar Kings tied the game in the bottom of the eleventh on a disputed play. A few minutes later, as midnight arrived, gunfire erupted both inside and outside the ballpark as soldiers carrying Tommy guns and civilians with private side arms began to fire into the air in celebration of the July 26 anniversary.

“Everybody was yelling, ‘Cuba Libre!’” Harrell recalled, and with all the gunfire, “it was pretty scary.”30 At that point, Sir Isaac Newton and the law of physics intervened, as bullets fired skyward a short time earlier began to rain down. When Red Wings coach Frank Verdi and Sugar Kings shortstop Leo Cardenas were both hit by stray bullets (but not injured seriously), the umpires took the teams off the field. The AP Wire dryly reported it was possibly the first time in baseball history that a game was called on account of gunfire.

The Red Wings arranged an immediate exit from Havana. In the early hours of July 26, Harrell caught a plane from Havana to Toronto, where that same evening he played in the International League All-Star Game. The next day Harrell flew back to Rochester in time for the July 27 regular-season game. Thus Harrell’s unique accomplishment of playing in three games in three countries in a space of two days.31

Returning to Rochester in 1960, Harrell batted .293. He led the team with 78 RBIs and again was named to the International League All-Star Team, this time as a third baseman. Immediately after the season, Harrell was one of five players the Cardinals traded to Buffalo, a Philadelphia Phillies affiliate, for outfielder Don Landrum. However, Harrell’s time in the Phillies organization ended when the Boston Red Sox grabbed him in the Rule 5 draft that November. Red Sox General Manager Dick O’Connell declared Harrell’s selection was for “infield insurance.”32

The 1961 Red Sox used Harrell in a role that was limited, to say the least. Appearing in 37 games with 38 plate appearances, and with only seven games started, Harrell batted .162 with one RBI for the season. Then, for 1962, he was assigned to Boston’s AAA affiliate, the Seattle Raniers of the Pacific Coast League. “My wife and family were living in Troy, New York, and we had another baby, so I said, ‘Oh good, I’m in Boston’–it was pretty close by,” Harrell reflected, “then I got sent out to Seattle. I wasn’t close by anymore.”33

In 128 games with the Raniers, Harrell batted .294 with 17 home runs, 78 RBIs, 71 runs, and 135 hits–leading the team in each of these categories. Harrell made his professional pitching debut that season, pitching two innings in a mop-up role. It would be the first of 10 similar relief appearances over the next four seasons in which he would give up 13 runs in 17 innings for a 6.88 ERA. Additionally, Harrell, now 34, assumed a role as a player-coach with Seattle, beyond the unofficial role of helpful teammate he had filled in prior years.

Harrell began the 1963 season with the Raniers, but in July was traded to the Portland Beavers, the Kansas City A’s AAA affiliate. Between the two teams, Harrell played in 125 games at third base and hit .268 with 10 home runs. In 1964, Harrell was back with Seattle, and split his time between the infield and outfield, hitting .254 with 14 home runs and 57 RBIs.

At the outset of the 1965 season the Red Sox assigned Harrell to be a player-coach with its AA Pittsfield affiliate. Pittsfield’s loaded roster included future major league All-Stars Reggie Smith and George “Boomer” Scott.

Harrell later recalled of these two young talents, “Scotty and Reggie both wanted to hit the most home runs, and they were in competition with each other. George would go off like a volcano and I’d calm ’em both down, and I’d tell ’em we’re all part of the same team, and it would help.”34 Smith himself credits Harrell as a “tremendous influence” on his own development, and describes how, “Billy taught me how to channel my energy, and had a very calming influence on me. He always had an anecdote or a story which managed to take a lot of tension out of certain situations.”35

After a month at Pittsfield, Boston assigned Harrell to the Toronto Maple Leafs, its new AAA affiliate in the International League. He hadn’t appeared in a game at Pittsfield, and the promise of playing again pleased him. In 51 games with the Leafs, Harrell batted .289. Under first-year manager Dick Williams, the team won the league playoffs.

In 1966, the Maple Leafs, again under Williams, repeated as league champions. As a player-coach with the team, Harrell continued to help young players develop. Future members of the 1967 Boston “Impossible Dream” team on the Leafs that year included Mike Andrews, Joe Foy, and Reggie Smith. Andrews described Harrell as being “like a father” to the younger players, adding how he, “learned so much from Bill, not only playing infield, but the way he carried himself off the field as well. He was a stabilizing influence with a young team plus he was the consummate pro and was always so positive.”36

That season Harrell’s performance at the plate fell to .173 in 33 games. Feeling “it was time to move on,” he retired from the game.37

Looking back on his role in the later years of his baseball career, Harrell said, “I was there to help the kids. You’d set a good example and keep them calm. You love the game. You’d love to make the big dough, but you love the game. You say to the young guys, ‘You’ll make it. You’ll make it.’ and you pitch them batting practice until your aim hurts, but you feel so good when they do make it.”38

After his retirement from baseball, Harrell took a position with the New York Department of Corrections in Albany and began a new career working with juveniles. On the transition, Harrell explained, “I liked helping the young ballplayers and I became a probation officer. I like helping kids. It makes you feel good when you can straighten some of them out, but you know how it goes. You can’t straighten them all out and some get into more trouble when they grow up, but at least you tried.”39

Following his retirement from his two careers, Harrell became active as a supporter of the Siena basketball program, regularly appearing at home games, including in a wheel chair when his health began to fail him in later years. Acknowledgements of Harrell’s accomplishments included the retirement of his number 10 Siena jersey in 2006, along with his induction into three Halls of Fame: Reading (Pennsylvania) Baseball (2006), Albany Sports (2010), and Metro Atlantic Athletic Coference (2014, shortly before his passing). In addition, Harrell’s mark on Siena basketball continues with the presentation each year of the “Billy Harrell Award” to the leading rebounder on the men’s basketball team.

Divorced in 1981 from his first wife, Vivian, Harrell married Miriam Canty in 1987. He lived with her in Albany until his death from natural causes on May 6, 2014. He was survived by his five children, 11 grandchildren, and 16 great-grandchildren.

“I loved it all. I have so many good memories and my life has been blessed,” Harrell said, in 2006, of his two careers in baseball and as a probation officer, “I’m just happy that I had the ability to do it and did it.”40

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Harrell’s player file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, and the following sites:

baseball-reference.com

retrosheet.org

SABR Bioproject- http://sabr.org/bioproject/

Acknowledgments

The author would like to acknowledge the following former teammates of Bill Harrell for their time provided in interviews, all of which assisted greatly in the preparation of this article: Mike Andrews, James “Mudcat” Grant, Dave Mann, Reggie Smith.

Also thanks go to Susan A. Washington of the Rochester (New York) Public Library for her assistance in researching the July 25, 1959, game in Havana, Cuba.

Notes

11 Larry Moffi and Jonathan Kronstadt, Crossing the Line, (University of Iowa Press, 1994), 152.

2 Alan Cohen, “The Hearst Sandlot Classic: More than a Doorway to the Big Leagues,” as published in the Fall 2013 Baseball Research Journal, http://sabr.org/research/hearst-sandlot-classic-more-doorway-big-leagues, accessed July 6, 2014.

3 “Harrell to Enter Siena ‘Hall’,” Schenectady Gazette, November 14, 1966, 55.

4 William Harrell, interview with the author, September 10, 2005.

5 William Harrell, interview with the author, February 13, 2013.

6 Ebony Magazine, “Future ‘Jackie Robinsons’: Amateur Teams Will Supply Major Leagues with New Crop of Negro Stars,” Vol. 7 Issue 7, May 1952.

7 Moffi and Kronstadt, Crossing the Line. An example of the difference in treatment of black players at that time is found in a June 1952 “Tabbing the Kids” The Sporting News feature. Within, amateur players drafted by major league teams were listed with their ages, together with the minor league teams to which they were assigned. Harrell was listed him as a 22-year-old drafted by Cleveland and assigned to Reading, PA, of the Eastern League and designated as a “Negro outfielder.” In the Boston Braves section, Henry Aaron was listed as “17-year-old Negro shortstop from Mobile, Ala.” No designation of race regarding white players appeared in the article. “Tabbing the Kids,” The Sporting News, June 25, 1952, 34.

8 William Harrell, interview with the author, January 13, 2006.

9 Ibid.

10 Douglas T. Branch, “Harrell Recalls Life in Majors,” Albany Times Union, June 17, 2001.

11 Harrell interview, September 10, 2005.

12 “Hank Greenberg Bans Games Where Negro Players Barred,” The Sporting News, April 8, 1953, 31.

13 Harrell interview, September 10, 2005.

14 Hal Lebovitz, “Exhibitions to Be Tribe Tests Rather Than Revenge Games,” The Sporting News, March 16, 1955, 23.

15 Hal Lebovitz, “Axe Swinging Only Sad Note in Sunny Outlook for Injuns,” The Sporting News, April 6, 1955, 21.

16 Harrell interview, September 10, 2005.

17 Harrell interview, February 13, 2013.

18 Harrell interview, September 10, 2005.

19 Hal Lebovitz, “’We Needed Bat Threat at Short’–Senor,” The Sporting News, November 2, 1955, 3.

20 Ibid.

21 Harrell interview, September 10, 2005.

22 Hal Lebovitz, “Thunder in Arizona–Its Injuns’ Clubs and Runners Feet,” The Sporting News, March 27, 1957, 24.

23 Hal Lebovitz, “”Wynn’s Sore Hip Making Tribe Wince,” The Sporting News, April 3, 1957, 8.

24 Hal Lebovitz, “Sister of Score Tipped Tribe to Catcher Brown,” The Sporting News, October 2, 1957, 30.

25 “Game Holds Headlock on Fans in Puerto Rico,” The Sporting News, February 12, 1958, 23.

26 Hal Lebovitz, “Handy Harrell Wins Bragan Nod on Hustle,” The Sporting News, May 28, 1958, 28.

27 Branch, “Harrell Recalls Life in Majors.”

28 James “Mudcat” Grant, interview with the author, January 8, 2006.

29 Ibid

30 Harrell interview, September 10, 2005.

31 A more detailed description of this game is available in the “Game Called on Account of Gunfire,” insert to “Billy Harrell: Two Careers of Helping the Kids,” by the author found in The National Pastime, No.27, 2007, 136-7.

32 Oscar Kahan, “Majors Draft 23 Players, Pay 497 Gees,” The Sporting News, December 7, 1960, 13.

33 Harrell interview, September 10, 2005.

34 Harrell interview, September 10, 2005, Ibid

35 Reggie Smith, interview with the author, January 12, 2006.

36 Mike Andrews, interview with the author, October 15, 2005.

37 Harrell interview, January 13, 2006.

38 Bill Swank, Echoes From Lane Field: A History of the Sand Diego Padres 1936-1957, (Turner Publishing Company, 1997), 146.

39 Ibid.

40 Ibid.

Full Name

William Harrell

Born

July 18, 1928 at Norristown, PA (USA)

Died

May 6, 2014 at Albany, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.