Fred Hatfield

Fred James Hatfield spent more than a half-century in baseball as a player, coach, manager, and scout. His origins are shrouded in the lint dust of the East Alabama cotton mills where his mother eked out a living. He was born in Lanett, Alabama, a mill town on the Georgia border. Fred’s baseball date of birth was always March 18, 1925, but on applications for admission to two different colleges he listed his birth as March 18, 1924, a date confirmed by his birth certificate. In baseball, it has always been better to be a year younger.

Fred James Hatfield spent more than a half-century in baseball as a player, coach, manager, and scout. His origins are shrouded in the lint dust of the East Alabama cotton mills where his mother eked out a living. He was born in Lanett, Alabama, a mill town on the Georgia border. Fred’s baseball date of birth was always March 18, 1925, but on applications for admission to two different colleges he listed his birth as March 18, 1924, a date confirmed by his birth certificate. In baseball, it has always been better to be a year younger.

Fred never knew his father. His mother, Emma Lou Wilkerson, was only 16 in 1915 when she married a millhand known as Fred Richard Hatfield, who claimed to be one of the feuding West Virginia Hatfields. When Emma Lou became pregnant eight years later, Hatfield disappeared, although it is not clear that he knew she was expecting. During Fred’s major-league playing days, he expected his father to re-establish contact, but it never happened.

Left on her own, Emma Lou moved with Fred to the tiny community of Reeltown, and from there to East Tallassee, Alabama, the place Fred listed as home until after he reached the majors. Emma rented a three-room company house and supported Fred and her younger brother, Jessie Aldridge, on the meager wages of a cotton mill worker in nearby Tallassee.

When Fred reached high school age, the high-school baseball coach in Troy, North Carolina, who had heard of Fred’s athletic ability and the family’s economic struggles, recruited young Hatfield. Emma Lou allowed Fred to move to North Carolina, where he lived with the coach. After playing football, basketball, and baseball at Troy, Hatfield was signed to a professional contract in 1942 by Boston Red Sox scout Herb Brett. A bonus of $1,200 in 1942 was a great deal for a boy raised in poverty. Assigned to Canton, Ohio, of the fast Class C Mid-Atlantic League, Hatfield struggled. He hit only .167 in 12 games before being shipped to Danville, Virginia. There, in the Class D Bi-State League, he improved his average to .260.

Baseball now had to wait until after World War II. After the 1942 season, Hatfield entered Troy (Alabama) State Teachers College (now Troy University), but after one term he enlisted in the Army and served throughout the war as a paratrooper. When he was discharged, Hatfield returned to Troy State as a physical-education major. He somehow managed to play football and basketball at Troy even though he had played professional baseball. He continued taking courses in the offseason at Troy and, after 1949, at Birmingham-Southern College. Hatfield eventually received a degree in secondary education from Troy in 1958. In the late 1940s, he also began refereeing basketball games, a practice he continued for a decade. He eventually worked his way up to officiating Southeastern Conference games. In December 1945 he had married Dorothy Estelle “Dot” Meyer. The couple had one son, Fred James “Jim” Hatfield, Jr., born in 1946.

Hatfield returned to baseball in 1946 and spent the next five seasons in the minors. At Roanoke (Class B Piedmont League) and Scranton (Class A Eastern League) he earned the nickname Scrap Iron for his willingness to take one for the team; he led each league in being hit by pitches. The Red Sox jumped Hatfield to Triple-A Louisville in 1948, but he quickly developed a reputation for drinking and carousing. The Sox demoted him all the way down to Class B, Lynn, Massachusetts, in the New England League. That demotion served as a wake-up call for Hatfield. He posted an all-star season at Lynn (14 homers, 74 RBIs, a .284 average, and 104 runs scored).

Boston promoted Hatfield to Birmingham of the Double-A Southern Association, where in 1949 and 1950 he posted the two best seasons of his career. For the first time, he displayed the power managers like to see in a third baseman. He smashed 25 home runs with a team-high 101 RBIs in 1949. In 1950 he homered 27 times and again drove in 101 runs. For the fourth and fifth consecutive seasons, he led the league in being hit by pitches. He also batted .300 for the first time (.300 even in 1950).

Hatfield’s Birmingham performance earned him a late season call-up by the Red Sox in 1950. He made his debut on August 30 in a game against the Chicago White Sox. Entering the game in the bottom of the ninth, he scored the winning run. In 10 games that fall he hit .250 and got a taste of the majors. His best memory of that time was of Bobby Doerr and Birdie Tebbetts smoothing the way for Hatfield in the clubhouse.

In the minors, Hatfield, a rail-thin, 6-foot-1 left-handed hitter, crowded the plate (contributing to his being hit so many times), stood straight with hands held high and bat straight, and tried to pull the ball. Red Sox manager Steve O’Neill saw Hatfield in the image of George Kell, whom O’Neill had managed at Detroit. The manager instructed Hatfield to choke up on the bat, drop his hands, and crouch at the plate. Another manager might have projected Hatfield to fill out and develop into a hitter with some power. After all, Hatfield had hit more homers at Birmingham than Walt Dropo had, and Dropo was nothing if not a power hitter. Fred complained later: “They took my home run stroke away from me.” With his new approach to hitting, Hatfield hit neither for power nor average. His first home run did not come until August 17, 1951, when his two-run shot helped the Sox to an extra-inning win in Washington. In his first full season in the majors, 1951, he batted a meager .172 in 163 at-bats.

O’Neill also encouraged the youngster to become a bench jockey, a practice Hatfield continued his entire baseball career. Umpire Durwood Merrill remembered Hatfield as “always chirping at the umpire from the dugout.” Among his teammates, Hatfield developed a reputation as a prankster and “a fun guy to be around.” Early in his career, however, Hatfield was especially hard on African-American players. Hatfield’s attitude mellowed in 1956 when for the first time he played with African-American teammates, Larry Doby and Minnie Minoso.

When the Red Sox retooled in 1952, Hatfield did not fit into their plans. A quick start (.320 for the first month) gave Hatfield trade value. On June 3, 1952, Boston packaged him in a nine-player trade that sent him, Walt Dropo, Don Lenhardt, Johnny Pesky, and Bill Wight to Detroit for George Kell, Dizzy Trout, Johnny Lipon, and Hoot Evers.

The trade to Detroit gave Hatfield the opportunity to play on a regular basis. He established himself as the American League’s slickest fielding third baseman, leading the circuit in fielding average and assists. Third basemen, however, are paid to hit, and for the rest of the 1952 season, Hatfield batted only .236 for the Tigers (.240 overall) without power on a last-place team.

Fred Hutchinson took over as manager of the Tigers in 1953. In June, the Tigers traded for Ray Boone, a third baseman with power, and Hutchinson installed Boone as his regular third baseman. That move relegated Hatfield to a utility role for the remainder of 1953 and for 1954. Splitting time between second and third, Hatfield did raise his average to .254 in 1953 and a personal best .294 in 1954. He did have the distinction of being the first pinch-hitter for Al Kaline; the only man to do so until 1970.

Another new Tigers manager, Bucky Harris, gave Hatfield the second-base job in 1955. Hatfield responded with personal highs of 61 walks, 15 doubles, and 8 home runs. His batting average, however, dropped to .232.

In 1956, Hatfield lost the second-base job to Frank Bolling. Fred expected to be traded and hoped he would be sent to the Yankees, but he went to Chicago instead. Outfielder Jim Delsing and Hatfield went to the White Sox in exchange for utility men Bob Kennedy and Jim Brideweser, and pitcher Harry Byrd. In Chicago, Hatfield again replaced George Kell, who went to Baltimore. Hatfield hit a respectable .261 and had a personal high 33 RBIs playing in over 100 games. His best game was a two-homer, four-RBI game July 15, 1956, in Yankee Stadium.

By 1957 it had become clear that Hatfield was just hanging on. In a part-time role again, he hit a weak .202. He later recalled his frustration: “When I got my pitch I fouled it off.”

After the season, Hatfield went to Cleveland with Minnie Minoso for third baseman-outfielder Al Smith and pitcher Early Wynn. The Indians in turn traded him to Cincinnati for reliever Bob Kelly in April 1958 but reacquired him for cash less than a month later, on May 18. After just three games, though, Cleveland sent him to San Diego of the Pacific Coast League. Hatfield thought he “was better than a lot of major-league players but couldn’t find a place to play.” No doubt he was a better fielder than many major-league infielders, but over parts of nine seasons, he batted just .242 without power.

His major-league playing career over, Hatfield played six more years in the minors. After two seasons in the Pacific Coast League split between San Diego and Spokane, he got the opportunity to manage. His 1960 and 1961 seasons as player-manager at Little Rock in the Southern Association had to have been his most gratifying since 1949-50. In 1960, he batted .277 with 14 home runs and his Travelers, who finished third in the regular-season standings, won the postseason playoffs. Hatfield earned his first Manager of the Year award. In 1961 he batted .315 for a third-place team. When the Southern Association folded after the 1961 season, Hatfield caught on as player-manager of the expansion Houston Colt 45s farm team in Modesto of the Class C California League. He guided the club to a second-place finish and batted .332. In 1963 he started the season as a player-coach with the Triple-A Denver Bears, a Milwaukee Braves farm club, but in nine games he hit a weak .188 with no extra-base hits. In June Detroit signed him to manage its team at Jamestown of the Class A New York-Pennsylvania League. He played in three games, batting .364, but it was obvious his playing days were over.

After Jamestown, Hatfield landed the job as baseball coach at Florida State University in Tallahassee. The university required its coaches to have a college degree, and to teach physical-education courses. Hatfield had the academic degree and managerial experience. It proved to be a good match; Hatfield made his home in Tallahassee until his death. In five years at the helm of the Seminoles, his team won 161 games while losing only 57. That .737 winning percentage was the highest in FSU baseball history. His 1968 team posted a 35-6 record, a winning percentage of .854. Hatfield’s teams made the NCAA tournament every year and the College World Series once. The Florida State University Hall of Fame inducted him in 1999.

Florida State, however, did not pay well, and Hatfield, concerned about retirement, returned to professional baseball in 1968. St. Louis hired him as a minor-league instructor and later as manager of its short-season team in Lewiston, Idaho, where he won the Northwest League pennant in 1970. During the winters, he operated the Cardinals’ winter instructional program.

In the early 1970s, Hatfield appeared to be on track for a major-league manager’s position. He returned to the Detroit organization, where he worked for eight years. At the helm of the Tigers’ Double-A franchise in Montgomery, Alabama, of the Southern League, Hatfield guided his club to two consecutive championships, winning both regular-season division and playoff titles in 1972 and 1973. Detroit promoted him to Triple-A Evansville of the American Association. After placing third in the East Division in 1974, Hatfield’s club jumped to the top of the East in 1975, and defeated Denver, the West Division leader, in the playoffs to take the league championship. Evansville then capped off the season by capturing the Junior World Series in five games over Tidewater. Hatfield was named American Association manager of the year.

After three championships in four years, Hatfield hoped for a major-league managing post. Being a good organization man, he downplayed his expectation, saying major-league coaches had a better shot at those jobs than successful minor-league managers. Even after a losing season at Evansville in 1976, Fred thought he had a shot at managing the expansion Seattle Mariners. Again, he was passed over, but Detroit manager Ralph Houk brought Hatfield to the Tigers as third-base coach for the 1977 and 1978 seasons.

Hatfield’s managerial career never again got back on a fast track. After Houk retired, the Tigers hired Les Moss as manager. Hatfield bounced from job to job. The Tigers gave him one more season in the organization, managing a bad 1979 Lakeland team in the Florida State League. Then he had another losing season in 1980 at Richmond of the International League. In 1981, Hatfield was reduced to managing a rag-tag co-op team at San Jose in the California League. He then scouted for Oakland for three years, 1982-1984. Hatfield finished his managerial career with winning records at Houston’s Asheville (South Atlantic League) farm, and the independent Miami Marlins of the Florida State League. For the remainder of his life Fred scouted, first for California (1987-1995) and then for the Yankees (1996-1998).

After the death of his first wife, Dorothy, in 1991, Hatfield married Shirley Baker Collins, who eased his final years. Together Fred and Shirley set out to unearth the mystery of Fred’s father. It turned out that the father had surfaced in his native West Virginia in 1923 using the name Pete Richardson (sometimes Samuel Pete and sometimes Pete Samuel). There, Hatfield/Richardson had married another woman in October 1923, five months before Fred’s birth in Alabama. After Shirley and Fred tracked down members of the Richardson clan, they discovered that Fred’s father had died in 1943. But Fred and a son of Pete’s had photos of their father in World War I uniforms; it was the same man.

Hatfield died on May 22, 1998, after a struggle with cancer. Shirley remembered Fred enjoying cooking, his grandchildren and great-grandchildren, and his dog, Biff. He is buried at Meadowwood Memorial Park in Tallahassee.

Sources

Communications with Shirley Hatfield in August and September, 2007. Mrs. Hatfield was especially helpful in filling in large gaps in Fred’s personal life.

Hatfield file, Baseball Hall of Fame

Obituary, The Sporting News, May 22, 1998

Dusen, George et al. The Detroit Tigers Encyclopedia (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing, 2003)

Merrill, Durwood. You’re Out and You’re Ugly Too! (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1998)

Peary, Danny. We Played the Game (New York: Black Dog and Leventhal Publishers, 1994)

Williams, Susan. “Family Unravels Mystery About Father,” Charleston Gazette, Charleston, West Virginia, November 23, 1994.

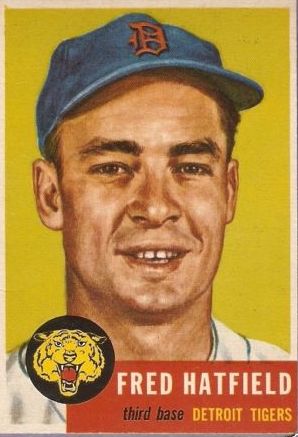

Photo Credit

The Topps Company

Full Name

Fred James Hatfield

Born

March 18, 1925 at Lanett, AL (USA)

Died

May 22, 1998 at Tallahassee, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.