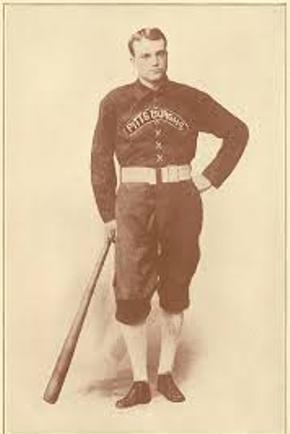

Billy Sunday

In the days before radio, Billy Sunday was the most successful evangelist America had ever known. The renowned preacher and temperance crusader found the Lord while playing for the Chicago White Stockings in the 1880s. He was an exciting player, speedy and daring on the base paths and acrobatic in the outfield. His earnest and buoyant personality made him popular with fans and players alike. Sunday chose a life of Christian service in 1891, but he never left baseball behind. Baseball was an integral part of his sermons, and he promoted games wherever he preached. Known as “the Baseball Evangelist,” Billy Sunday was always identified as a baseball player, and for his supporters he was a model of Christian manliness and American decency.

In the days before radio, Billy Sunday was the most successful evangelist America had ever known. The renowned preacher and temperance crusader found the Lord while playing for the Chicago White Stockings in the 1880s. He was an exciting player, speedy and daring on the base paths and acrobatic in the outfield. His earnest and buoyant personality made him popular with fans and players alike. Sunday chose a life of Christian service in 1891, but he never left baseball behind. Baseball was an integral part of his sermons, and he promoted games wherever he preached. Known as “the Baseball Evangelist,” Billy Sunday was always identified as a baseball player, and for his supporters he was a model of Christian manliness and American decency.

William Ashley Sunday was born near Ames, Iowa, on November 19, 1862, the third son of Mary Jane (Cory) and William Sunday. Mrs. Sunday’s father owned a large farm and two mills, and she and her bricklayer husband lived on that farm. Young Billy never saw his father, who had enlisted in the Union Army in August and died of pneumonia in an army camp a month after his namesake was born.

Mary Jane Sunday stayed on her family’s farm. She married again, but her second husband was a drunkard who deserted the family. In 1874 she sent Billy and one of his older brothers to the Soldiers’ Orphans Home in Davenport, Iowa. There the boys were trained in hygiene and manners and given some religious guidance. They also received a good education and the chance to participate in games and athletic events.

In 1876, when his brother turned 16 and was sent home, Billy also returned to Ames. He went to work for his grandfather, but after they quarreled the youngster moved to nearby Nevada, Iowa. There he found a job that gave him room and board, and he enrolled in the Nevada high school. He played for the local baseball team and ran in regional foot races, earning a reputation for his speed. In 1881 a running team in Marshalltown, Iowa, recruited Sunday, and he moved there before the end of his senior year in high school.

Sunday found a job in Marshalltown and soon joined the town baseball team along with the running team. In the fall of 1882 Marshalltown beat a stronger Des Moines team, 15-6. Sunday played left field, slugging three doubles and scoring four runs.

Marshalltown was the hometown of Adrian “Cap” Anson, player-manager of the Chicago White Stockings. On a visit home, Anson heard about Sunday’s baseball skills from a relative. The veteran watched Sunday compete in a foot race, and he liked what he saw. Anson invited Sunday to train with the Chicago team in the spring of 1883and signed him as a substitute outfielder. While primarily interested in Sunday’s speed and athletic potential, Anson also liked the polite and eager twenty-year-old, and he took the newcomer under his wing.

In spite of Anson’s tutelage, Sunday’s rookie year was forgettable. He played in only 14 games, collecting 13 hits with 18 strikeouts. In the field, he made ten putouts and six errors. Still, Anson was not ready to give up on Sunday, and he signed the unpolished speedster for 1884.Sunday’s second season was no better than his first, although he did impress his teammates in spring training. Anson wanted to give Sunday a chance to show off, so before an exhibition game he arranged a 100-yard race between the rookie and Fred Pfeffer, the team’s second baseman. Pfeffer was a very good runner, but Sunday won the race easily.

Sunday played a total of 43 games in 1884, mostly in right field when Mike “King” Kelly appeared behind home plate and a few stints in center when George Gore was hurt. Sunday impressed no one with his play.His teammates didn’t fare well either, and that year Chicago finished fourth in the league. Both manager Anson and owner Albert G. Spalding blamed the team’s poor performance on the players’ drinking and partying. Anson had a strict training regimen for his players, but apparently most of them ignored it. Sunday did not, and that fact, along with his manager’s continuing faith in his potential, earned him another contract.

Hoping to improve the team’s performance in the 1885 season, Spalding required an abstinence pledge from the Chicago players, and any of them who were caught drinking would have their salaries reduced. Sunday had no problem adhering to the policy. Although he did socialize with his teammates, Sunday was at worst only a moderate drinker. In his autobiography he wrote: “I never drank much. I was never drunk but four times in my life. I never drank whisky or beer; I never liked either. I drank wine.” When he went “to the saloons” with his teammates, “I would take lemonade or sarsaparilla.”1

Whether because of or in spite of the no-drinking rule, the White Stockings played well right out of the gate. To capitalize on the good start, Anson wanted to put his best team on the field, and Sunday did not get a lot of playing time. Again he played mostly in right field, with a few appearances in center. In all he played in 46 games, showing some improvement over his first two seasons.Even in limited appearances, Sunday was a fan favorite. The crowds enjoyed watching him sprint after fly balls in the outfield, but they cheered even louder for his daring steals and legged-out hits. In late August Anson scheduled a race between Sunday and a professional sprinter. Sunday ran the 100 yards in ten seconds, beating the professional by nearly three feet.

The 1885 Chicago White Stockings dominated the National League, winning the pennant with an 87-25 record. They earned the right to play the St. Louis Browns, winners of the American Association pennant, in a best-of-seven “US Championship Series.” In spite of their great season, the Chicago team still suffered from bad off-field habits.Center fielder George Gore was reportedly drinking at the end of the season, and after a lackluster performance in the first playoff game he was suspended. Sunday took Gore’s place, playing in center and batting second in the rest of the games. He performed respectably, going six for 22 at the plate and scoring five runs, along with getting to everything that came his way in center field. The series as a whole was less respectable, characterized by unruly fans and heated arguments between the umpires and players, and the official score was three wins for each team and one tie.After the playoffs, Sunday regained some lost honor for Chicago. In St. Louis, he ran a 100-yard race against Arlie Latham, third baseman for the St. Louis Browns and the fastest runner in the American Association. Sunday won handily, with a reported time of 10.25 seconds.

For the 1886 season, Spalding again had his players sign an abstinence pledge. Unbeknownst to them, he also hired detectives to follow the players and report on their off-field activities. In late July, Spalding presented the detectives’ report to the team. While Sunday, Anson, and several others were exonerated, seven players, including Mike Kelly and George Gore, were fined for drinking and keeping late hours. Regardless of the players’ behavior or their relationship with management, they played well. Chicago was locked in a tight pennant race right up to the final games of the season, when they emerged in first place again. They had a playoff rematch with St. Louis, but that time around St. Louis won.

Sunday played in only 28 games in 1886, and he was not involved in the playoffs. He contracted an eye infection in late August, but the main reason for his reduced playing time was the season-long pennant race, during which Anson rarely used his bench players. On the few days when Sunday did take the field, he played a little better than in previous seasons, raising his fielding average 89 points, to .914.

While the 1886 baseball season would have been a disappointment for Sunday, what happened off the field changed his life forever. Sometime in the spring he began attending services and youth group meetings at the Jefferson Park Presbyterian Church in Chicago, which was near both the ballpark and Sunday’s rooming house. There he met Helen Amelia “Nell” Thompson (1868-1957), a devout young woman whose father was a successful businessman. Although William Thompson disapproved, his daughter and the Chicago ballplayer became good friends. Sunday joined the church, and by the end of the summer he was regarded as a clean-living church-goer. The year before, he had started working in the off-season as a railroad fireman in Iowa, and over the winter he wrote to Nell Thompson from Iowa. During the holidays Sunday visited Chicago and the Thompson household.

Meanwhile, A.G. Spalding had decided to remake his baseball team. He blamed the loss of the playoffs on the drinking and poor habits of several of his key players, targeting Mike Kelly as the ringleader. In1886 Kelly led the league in both batting average and runs scored, but Spalding was nevertheless exasperated with his flamboyant star. First the strong-willed Spalding sold two outfielders and a pitcher. Then in February the news broke that Kelly had been sold to the Boston Beaneaters for the then-unheard-of sum of $10,000. Spalding had chosen to replace Kelly in the Chicago outfield with the speedy, sober, and disciplined Billy Sunday.

Sunday began the 1887 season in center field, fielding brilliantly but not hitting well. When Anson switched him to right field, his hitting improved measurably. At the end of June he injured his ankle, and he was out for over a month.Sunday returned to the White Stockings in early August, but for the rest of the season he did not play regularly or well. Nor did his return help his team’s performance. In early August Chicago was two games out of first, but when the season ended they were in third place. Sunday had played in 50 games, most of them in May and June.

In August and September of 1887 Sunday had more on his mind than baseball. He and Nell Thompson had gotten very close. He went to Iowa in July while his ankle was healing, and when he returned to Chicago in August he took an interest in evangelical work. He started speaking to Sunday school classes and YMCA groups and regularly attending religious meetings, both in Chicago and on the road.It was probably in early August that Sunday began going to the Pacific Garden Mission, an evangelical Christian mission in Chicago. It was there that, sometime in the late summer or early fall, Sunday publicly dedicated his life to the service of Christ.

During the winter of 1887-88, Sunday made arrangements to take courses in elocution and rhetoric at Evanston Academy, part of Northwestern University. In exchange for the courses, he agreed to coach the university’s baseball team during their winter practice sessions. On the night of January 1, 1888, Sunday proposed to Nell Thompson.

Later that month, the Pittsburgh Alleghenys purchased Sunday’s contract from Chicago. The Pittsburgh team was new to the National League, and it had difficulties on and off the field. Several of the players drank and kept late hours, and in 1887 the team finished sixth. The Pittsburgh center fielder had been fined several times for drinking, and the team’s management was in search of a competent and sober replacement. Billy Sunday was just the kind of player they wanted.

Sunday showed up in Pittsburgh in great shape, after practicing all winter with the Northwestern team. Playing center field every day improved his game. He hit well, dashed around the bases with abandon, and brought the stands to life with his running catches.By early June, Sunday was one of the team’s best hitters, and he led the league in stolen bases.Pittsburgh fans liked Sunday not only for his game but also because he attended a local Presbyterian church and taught Sunday school.

In early September, Sunday left the team to go to Chicago, where he and Nell Thompson were married on September 5.Sunday rejoined the team in Pittsburgh three days later, accompanied by his new bride. He had been playing excellent baseball in August, and after his wedding he continued his dramatic play in the field and on the base paths, making good contact at the plate and running out infield hits. His fine season came to an end with a knee injury on September 29.

Sunday played 120 games in 1888. He was ranked among the league’s top fielders and led his team with 69 runs scored. Although he missed the last two weeks of the season, he finished third in the league in stolen bases with 71. Still, his team finished sixth again.

After Sunday had settled his 1889 contract with Pittsburgh, he and Nell took a wedding trip before returning to Chicago. He began taking Bible classes at the Chicago YMCA and was such an eager student that the YMCA offered him a job. Sunday accepted a part-time position, continued his Bible study, and started leading prayer meetings. He continued holding religious meetings at the Pittsburgh YMCA when he returned in the spring, and as the season went on he spoke at YMCAs in other cities when the team was on the road.

Sunday opened the 1889 season in right field. During the off-season, Pittsburgh had signed Ned Hanlon, an accomplished outfielder, to play center. Sunday injured his thumb in the first game and was out for two weeks. When he returned in early May, he picked up where he had left off the previous year, dramatically snaring everything hit his way and making enough contact at the plate to leg out hits, steal bases, and score runs. In spite of Sunday’s contributions, once again his team wasn’t winning.

At the end of June Sunday was ill, but he kept playing. His fielding was still good, but his hitting and base running tailed off. In early July he was treated for a carbuncle on his hip and missed the rest of the month. At the same time, the Pittsburgh manager was having mental health problems, and some of the players weren’t getting along. The manager eventually had a breakdown, and Ned Hanlon was appointed player-manager.

When Sunday returned to the field in August, he was running well again, but he had lost his batting eye. The new manager benched him, and he didn’t get back on the field until the last two weeks of the season. Although he ended the year in good form, illness and injury cost him. Sunday had played in only 81 games, a disappointing season after his fine showing the year before.

Regardless of his performance, at the end of the 1889 season Sunday wasn’t sure where he would be playing in the spring of 1890. Most of the players in the National League were in the same situation. Over the past year, John “Monte” Ward, the talented and respected shortstop of the New York Giants, and the players’ association that he led, the Brotherhood of Professional Base Ball Players, had been arguing with the owners of National League teams over players’ contracts. In July the Brotherhood, with members from all National League teams, had considered a strike. Instead they decided to form their own league for the 1890 season, with teams in every National League city. The Brotherhood was to meet in early November to incorporate the Players’ League.

Sunday, who had union experience from his railroad job, had joined the Brotherhood in the fall of 1887; in 1889 he was the vice-president of the Pittsburgh branch. In spite of his involvement with the Brotherhood, at the end of the season Sunday promised the Pittsburgh team that he would re-sign with them. However, when the Pittsburgh Players’ League team was incorporated in November, Sunday signed on with them instead. After he returned home to Chicago, Sunday reconsidered his position. His conscience told him that he was obligated to honor his promise to the National League team, and he withdrew his pledge to the Players’ League. He spent the winter working for the Chicago YMCA.

Sunday, who had union experience from his railroad job, had joined the Brotherhood in the fall of 1887; in 1889 he was the vice-president of the Pittsburgh branch. In spite of his involvement with the Brotherhood, at the end of the season Sunday promised the Pittsburgh team that he would re-sign with them. However, when the Pittsburgh Players’ League team was incorporated in November, Sunday signed on with them instead. After he returned home to Chicago, Sunday reconsidered his position. His conscience told him that he was obligated to honor his promise to the National League team, and he withdrew his pledge to the Players’ League. He spent the winter working for the Chicago YMCA.

After the Players’ League was formed, three-quarters of the National League’s players defected to the new league, and the Pittsburgh team was decimated. Sunday and two others were the only returning players; of the newcomers, only one, first baseman Guy Hecker, was an experienced player. Hecker was named player-manager, and he picked Sunday for team captain. Pittsburgh was, in a word, terrible, and they posted a dismal record of 23-113. Sunday did all he could, remaining a fan favorite on a team with little else to cheer about.

By the end of August, Pittsburgh was in serious financial trouble. At the same time, the surprisingly good Philadelphia National League team was making a run at the pennant. Needing another good outfielder, on August 22 Philadelphia traded two capable rookies and $1000 cash to Pittsburgh for Billy Sunday. Philadelphia’s new center fielder played hard and well, but when the season ended his team finished a disappointing third.

The 1890 season was an all-around disappointment for baseball.The Players’ League dissolved and most of the players returned to their former teams for the 1891 season. The Philadelphia team had retained two excellent players from their 1889 outfield, Sam Thompson and Billy Hamilton, and Ed Delahanty rejoined them for 1891. In the off-season, Philadelphia looked to be the strongest team in the National League.

Sunday was signed by Philadelphia as one of two backup outfielders. Not only would he probably not see much playing time, he also had gotten more involved with the Chicago YMCA. During the winter the YMCA offered him the position of Assistant Secretary of the Religious Department. He didn’t accept it at first, but then he began seriously considering leaving baseball. By March Sunday had made his choice. He obtained his release from Philadelphia, then turned down an offer from Cincinnati.

Sunday’s new position involved getting speakers for daily midday prayer meetings and leading other prayer meetings himself, as well as distributing religious tracts on street corners and talking to drunks in saloons. He worked from 8:00 a.m. to 10:00 p.m., six days a week, for $83 a month. He threw his heart, soul, and considerable energy into his ministry, and his efforts were noted and appreciated by the YMCA’s leaders.

In early 1893, the well-known evangelist J. Wilbur Chapman came to Chicago. He was in search of an assistant for a series of revivals in the Midwest, and the YMCA recommended Sunday. For the next three years Sunday accompanied Chapman, learning the mechanics of holding revivals and honing his pastoral skills in prayer meetings and personal visits. In late 1895, Chapman accepted a pastorate in Philadelphia, and Sunday went out on his own.

Sunday’s first revival was in Garner, Iowa, in January 1896. He spent the next dozen years holding revivals in the rural Midwest. Initially, advertising was a major concern for him, along with the fact that he had only one sermon, a talk on “Earnestness in Christian Life.” He capitalized on his reputation as a ballplayer to generate interest in his revivals, making sure that local newspapers knew who he was. He began using some sermons that Chapman had given him, but as time went on he found his own voice and started telling stories about the things he knew, especially baseball and temperance.

Sunday displayed a natural gift for rhetoric, especially in creating realistic images and catchy descriptions. Retaining his athletic energy, he was in constant motion when he preached, using acrobatics and dramatic movement to illustrate his points. Because of his baseball past and his physical preaching, along with his straightforward approach and down-to-earth language, Sunday was able to attract large numbers of men to his revivals. He embodied a man’s religion, and men understood his message. In his sermon “A Plain Talk to Men,” he said, “Many think a Christian has to be a sort of dish-rag proposition, a wishy-washy, sissified sort of a galoot that lets everybody make a doormat out of him. Let me tell you the manliest man is the man who will acknowledge Jesus Christ.”2

In 1903 Sunday was ordained by the Presbyterian Church. Although he was officially a Presbyterian, Sunday’s ministry was always nondenominational, and he didn’t emphasize theological matters. “I am an old-fashioned preacher of the old-time religion,that has warmed this cold world’s heart for two thousand years.”3He preached a simple message of temperance and salvation through Jesus Christ, an accessible Christianity expressed in the uncomplicated language of America’s heartland. “I don’t use much high-falutin’ language. I learned a long time ago to put the cookies and jam on the lowest shelf.”4

Within two years Sunday had developed a special sermon on temperance, “Booze, or Get on the Water Wagon.” He used it for the first time in Burlington, Iowa, and a few days later the town limited the hours saloons could be open. In 1907, when he couldn’t fill his tabernacle for a revival in Fairfield, Iowa, Sunday put together two baseball teams from the town’s businesses and scheduled a game between them. The evangelist showed up for the game wearing one of his old uniforms and played for both teams.

In early 1908 Sunday held his first large-scale revival, in Bloomington, Illinois. That was followed by an invitation from Prohibition forces in Spokane, Washington. As his revivals grew larger, Sunday began holding services for particular groups of people, including separate services for women and men. In one of his sermons for men, Sunday talked about three of his Chicago teammates, Mike Kelly, Ned Williamson, and Frank Flint, star players who drank themselves into illness and early death. At the end of the sermon, Sunday asked, “Did they win the game of life or did I?”5

By then Sunday was widely recognized as a popular and successful evangelist who was not only a former baseball player but also a force in the Prohibition movement. In 1911 he began holding revivals in the Northeast, culminating in a 1914 appearance in Carnegie Hall. Twice during that time the national magazine Collier’s asked him to choose an all-star baseball team.

During a two-month revival in 1914 in Denver, Colorado, he umpired a game between the Denver Bears and Sioux City Indians, garnering as much press coverage as the game. In early October he led a huge Prohibition parade the day before he gave his “Booze” sermon. Colorado enacted statewide Prohibition a month later. While Sunday was in Denver, American Magazine published its poll on “The Greatest Man in the United States.” Sunday placed eighth, tied with Andrew Carnegie.

On January 18, 1915, Sunday met with President Woodrow Wilson at the White House. Afterwards he had lunch with William Jennings Bryan and then preached downtown, in Convention Hall. Two months later he held a large revival in Philadelphia, reportedly winning 42,000 souls to Christ. While there he played in an old-timers’ baseball game; the 53-year-old evangelist hit a home run.

In the spring of 1916, Sunday held a revival in Baltimore. Five New York Yankees were there, including Frank “Home Run” Baker. The ballplayers were among those who came forward to accept Christ and shake hands with the retired outfielder. In the fall Sunday went to Detroit for two months, and he delivered his “Booze” sermon to 29,000 men. On the last night of the revival, two players from Sunday’s era, Charlie Bennett and Sam Thompson, came forward with the crowd to take his hand. Two days later, Michigan voted to enact Prohibition.

Sunday was at the pinnacle of his career. After three months in Boston, where he claimed 65,000 converts, he went on to New York. There he opened his largest revival with these words:“I notice you’re the same warm-hearted, enthusiastic bunch you used to be when you sat in the grandstand and bleachers when I played at the old Polo Grounds. It didn’t matter if a fellow was on the other side or not. If he made a good play he got the glad hand rather than the marble heart.”6A few weeks later Sunday began advocating national Prohibition. When the New York revival ended in mid-June, over 98,000 people had accepted his call to salvation.

The US joined the Allies in World War I while Sunday was in New York. He was an energetic supporter of the war, selling millions of dollars in Liberty Bonds and rallying thousands of volunteers. In July Baseball Magazine asked his opinion on whether baseball should be suspended during the war. He said, “Baseball is needed now more than ever before. What are soldiers if they are not good athletes?”7That fall, while appearing in Los Angeles, he and his staff played a baseball game to raise money for servicemen against a team of movie stars led by Douglas Fairbanks Jr. The movie stars won, 1-0.

Sunday’s stature and importance remained strong throughout World War I and the enactment of Prohibition. In the 1920s, his influence waned, and his later revivals were held in smaller cities, with smaller crowds. However, his sermons on salvation, temperance, and personal decency still commanded attention. Sunday remained popular, and he continued preaching until a week before he died.

Sunday attended one game of the 1935 World Series between the Chicago Cubs, successors to his old White Stockings team, and the Detroit Tigers. He said he was so disgusted with the umpiring that he listened to the rest of the games on the radio. A month after the World Series ended, on November 6, Billy Sunday died of a heart attack at his brother-in-law’s home in Chicago. He is buried in Forest Home Cemetery there.

Billy and Nell Sunday had four children. Nell often travelled with her husband, later becoming his business manager,and the couple hired a full-time governess to take care of their children. Both parents were closest to their oldest child, Helen E. Sunday (1890-1932). She married Mark P. Harris in 1913, and they lived in Michigan. The Sundays’ three sons, George M. Sunday (1892-1933), William A. Sunday Jr. (1901-1938), and Paul T. Sunday (1907-1944), worked on their father’s campaigns at various times. All three men had unstable lives, including multiple marriages and financial troubles.

In 1911, the Sundays moved from Chicago to Winona Lake, Indiana. There Nell Sunday, who outlived her husband and all four of her children, continued a life of Christian service. She died on February 20, 1957, and is buried in Chicago next to her husband. The Sundays’ home in Winona Lake is preserved as a museum, maintained by the Winona History Center at Grace College.

Sources

This biography has been adapted from the author’s Sunday at the Ballpark: Billy Sunday’s Professional Baseball Career, 1883-1890 (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2000), and “The Baseball Evangelist Throws Out John Barleycorn: Billy Sunday and Prohibition,” in The Politics of Baseball: Essays on the Pastime and Power at Home and Abroad, ed. Ron Briley (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2010), 25-37.

Notes

1 Billy Sunday, “Mr. Sunday’s Autobiography,” in Billy Sunday, the Man and His Message, by William T. Ellis (Philadelphia: John C. Winston, 1936), 499.

2 Billy Sunday, “A Plain Talk to Men,” in Ellis, 204.

3 Quoted in Ellis, 146.

4 Quoted in Billy Sunday, by D. Bruce Lockerbie (Waco: Waco Books, 1965), 24.

5 Billy Sunday, “The Devil’s Boomerangs, or, Hot Cakes Off the Griddle,” in Lockerbie, 31.

6 Quoted in Billy Sunday Was His Real Name, by William G. McLoughlin, Jr. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1955), xix.

7. Billy Sunday, “A Defense of the Grand Old Game,” Baseball Magazine, July 1917, 361.

Full Name

William Ashley Sunday

Born

November 19, 1862 at Ames, IA (USA)

Died

November 6, 1935 at Chicago, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.