Bruce Caldwell

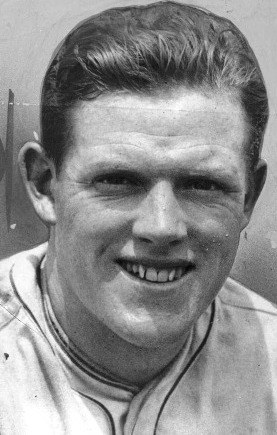

The pride of Ashton, Rhode Island, stood 6 feet tall and was made of 190 pounds of rippled muscle. He was a blond-haired, freckle-faced boy with a good-natured smile. Behind his friendly face an above-average mind was at work. Coming from a home with no economic advantages, he rose to academic heights and professional success; he became an All-American college football player at Yale, played in major-league baseball and football, managed prizefighters, and briefly was more famous than Babe Ruth in the year the Bambino hit his record 60 home runs.

The pride of Ashton, Rhode Island, stood 6 feet tall and was made of 190 pounds of rippled muscle. He was a blond-haired, freckle-faced boy with a good-natured smile. Behind his friendly face an above-average mind was at work. Coming from a home with no economic advantages, he rose to academic heights and professional success; he became an All-American college football player at Yale, played in major-league baseball and football, managed prizefighters, and briefly was more famous than Babe Ruth in the year the Bambino hit his record 60 home runs.

He lived a cosmopolitan life but always remained a country boy, returning to the small town.

In his lifetime, he wore the flannels of the 1928 Cleveland Indians and the 1932 Brooklyn Dodgers, the shoulder pads of the New York Giants, the bars of a lieutenant commander in the US Navy, and the robes of a judge.

Bruce Caldwell was not the typical Yale boy. He wasn’t the well-to-do and well-prepped student who normally came to wear the Elis’ blue quilted football jersey or the baseball uniform with the Handsome Dan patch over the heart.

Instead of the leafy suburbs, Caldwell came from the impoverished American melting pot. He was born on February 8, 1906, in Ashton, Rhode Island, a mill village a few miles north of Providence. His father, James Young Caldwell, came with his family from Scotland when he was 5 years old and went to work at 9 as a weaver in the Ashton Mill on the banks of the Blackstone River, one of the conduits of the Industrial Revolution. James also pushed a broom at the Central Grammar School in nearby Valley Falls.

Bruce’s mother, Harriet Amanda Jackson, was born in Ashton. She and James had two children, Bruce and a daughter, Eva. At St. John’s Episcopal Church, the family heard the homilies of the Rev. William Pressey who baptized and confirmed the reserved youngster.

James and Harriet named their son after Robert Bruce, the 14th-century Scottish king. Bruce was a good student and a fine athlete at Cumberland High School, from which he graduated with 31 classmates on June 23, 1923. Though he stood out physically, Bruce was no dumb jock. He was a member of the National Honor Society. At the high-school graduation he participated in a debate the US government should own and operate coal mines.

Ashton is a part of the town of Cumberland. The town is not without its distinctions in baseball culture. Outfielder Rocco Baldelli and the Farrelly brothers, who wrote and directed the baseball-themed film Fever Pitch, grew up there. So did Bruce Caldwell. But the memory of Caldwell, one of the greatest Rhode Island-born athletes ever, is unknown to most people in his home state. His deeds blow anonymously by like a summer breeze.

As a halfback at Yale, Caldwell was a fast, physical ball carrier who cut well and punished his tacklers. (The 1927 Elis were retrospectively named the national champion by the College Football Researchers Association.) In his sophomore year he had been knocked out of a starting role by injuries. At the start of the 1927 season he was the sixth-string halfback. By season’s end he had been named an All-American by the Central Press Association, the Hearst Newspapers, and New York Sun sportswriter Lawrence Perry. This despite the fact that he was suddenly kicked off the Eli team with two games left.

Socially, Caldwell was out of place in the Yale backfield. His teammates prepped at the blue-blooded academies of Andover, Exeter, Hill, Hotchkiss, Carteret, Loomis, and St. Mark’s. Bruce graduated from Cumberland High, where he earned recognition for perfect attendance. At Yale he cleared tables at the Y Club in exchange for his meals and worked summers at a loom in the Ashton Mills to repay the loans for his Ivy League education.

On November 8, 1927, the Providence Evening Bulletin startled its readers with the news that their local favorite had been declared ineligible. Before enrolling at Yale, he had entered Brown University in the fall of 1923 and played in two Brown freshman games. Yale’s regulations, in an effort to end what was called tramp football in those days, barred students from a particular sport if they had played in freshman or varsity athletics in the sport at any other college. Caldwell had played two minutes for the Brown freshmen.

Though barred from the Eli gridiron, Calwell remained at Yale and in the spring he returned to the Yale baseball team, coached by Smoky Joe Wood. A second baseman, he could hit for average and power. Major-league teams were interested in him. He finished the baseball season with a .413 average.

After the last game of the season, Caldwell signed with the Cleveland Indians for a $3,000 bonus and a contract calling for $600 a month. His coach, Smoky Joe, had advised him. (Wood had played as an outfielder for the Indians after his arm went bad while he was with the Boston Red Sox.) The Indians were in fifth place at the time and the team’s first-year general manager, Billy Evans, was trying to strengthen the team. Wood predicted that within a couple of years Caldwell would rival Rogers Hornsby as a batter. (Caldwell certainly outranked the Rajah as a scholar; he graduated from Yale magna cum laude.

At the time Caldwell signed, the Indians needed a hitter with star potential. That season they were hot in April, good in May, and sinking like a stone in June. They had lost 21 of their last 27 games, including 11 losses in12 games, in the month before Caldwell signed. Caldwell seemed like an offensive cure, a puzzle piece to help right the team.

The Sporting News suggested that Caldwell’s fielding might be a hindrance: “It is said that the boy is a natural hitter, but only an ordinary fielder. That he will never become a major league second baseman is certain, and Billy Evans intends trying him at first base.

Cleveland tried Caldwell and six others at first base that year, including 34-year-old George Burns and the versatile Lew Fonseca. That didn’t leave much room for the subpar fielding Caldwell, except as a pinch-hitter. Between June 30 and September 7 he played in 14 games, pinch-hitting in all but one.

Suddenly the outlook brightened. Manager Roger Peckinpaugh installed Caldwell in right field on September 8. He started in four consecutive games and went 4-for-14. He singled and tripled against the Chicago White Sox. He singled, doubled, and stole a base against the St. Louis Browns. He handled seven fly balls in the field without trouble, and recorded one assist.

But the skein was a farewell jaunt. Caldwell’s cumulative batting average was .222. It was clear that he was not going to bring the offensive thunder that he had demonstrated in New Haven. His future with the Indians may have been bleak, but football beckoned. Caldwell signed a one-year contract with the New York Giants of the National Football League. He was to be paid $500 per game plus 25 percent of the net profits.

Caldwell said signing with the Giants for just one year was intentional. “I always liked baseball better. … That’s why I haven’t any plans beyond this season with the Giants,” he told F.G. Vosburgh of the New Haven Journal Courier. “After the football season is over, I’m going to start thinking about the baseball season with the Cleveland Indians … and most of all, I want to make good as a big-league ball player. It’s the game of games for me.”

Caldwell had an off-and-on season with the Giants. Often hampered by injuries, he played seldom, often riding the bench entirely in a game. Complete statistics for the period are not available, but Caldwell appears to have gained less than 100 yards rushing. He completed one pass and had two pass receptions. A shining moment came against the Green Bay Packers when he scored the Giants’ only touchdown in their 6-0 victory on a 30-yard pass reception. Against the Giants’ intracity rival the New York Yankees, Caldwell ran for a touchdown and drop-kicked a field goal as the Giants won, 10-9. (The game was played at Yankee Stadium, then five years old.)

But the competition in the NFL was tougher than in college. Caldwell was slowing down under the pressure of larger, stronger, and older opponents than he faced in college. This was grind-it-out football in light pads. You played both ways. You got hit, hurt, and continued to take the handoff, progressing a yard at a time. In the game against the Yankees, three different Giants took the ball in the last three yards gained before Caldwell plunged over. This was slug-it-out warfare.

The transient nature of pro football was no doubt evident to someone as intelligent as Bruce. Five days before the Yankees game he said he much preferred horsehide to pigskin. For the second time in three months, he was making other plans.

On Sunday, Nov. 4, The Giants played in the mud before a tiny Polo Grounds crowd of 3,000. It was a wet, frustrating 0-0 tie with the Frankford Yellow Jackets. Unable to gain traction, both teams spent the day burying their faces and cleats in the mud, poking fists, attempting vainly to force fumbles. There were 29 punts. A missed field goal in the opening minutes was the only legitimate scoring attempt. The Giants tried an aerial attack, tossing 12 passes in their last possession, but they couldn’t reach the red zone. Caldwell injured his leg on the first play of the day and left the game.

The Giants played again two days later, and Caldwell rode the bench as teammates Hinky Haines and Bill Eckhardt scored touchdowns to lead the team over Pottsville, 13-7, before 20,000 at the Polo Grounds. Haines swept around the ends with immunity. Eckhardt consistently ripped through the Maroons’ defense for good gains. Caldwell had plenty of time on the bench to contemplate his future.

Caldwell sat out the next game, on the 11th, and played briefly on the 18th after injuring his ankle. On the 25th the Giants played the Providence Steam Roller in Providence, more or less Caldwell’s home turf. The Steam Roller, who eventually won the league championship, blanked the Giants, 16-0. Caldwell was on the field in three quarters but carried the ball just twice. The first time he barely reached the line of scrimmage. Before the game the hometown crowd honored him and presented him with luggage. It could well be that he used the luggage to pack up and leave the Giants. He had just two weeks left as a New York Giant.

On December 2 the Giants lost to the Yankees again. Caldwell started the game, playing the first half until Mule Wilson took his place, and “failed to make any headway against the Yanks,” said the New York Times. He started his last game as a Giant the following week against Frankford in the cold and snow, but carried the ball just twice before he was replaced.

It was almost a ceremonial ending. Caldwell was still a name. His status was featured in the newspaper accounts, “Led by Bruce Caldwell, former Yale back, the Giants could not get started. …”

Had the Giants kept him on the team just to sell tickets? His return to Providence had set an attendance record. And the Polo Grounds crowds were consistently averaging 20,000 despite what emerged as a disappointing 4-7-2 record, good for only sixth place in the 10-team league.

The parting came on December 11, 1928, when the Giants released Caldwell. The next day, the New Haven Journal Courier wrote that team officials believed that Caldwell was “not … rugged enough to stand the pro game.”

“Caldwell is well liked by everyone on the club,” team secretary Harry March told the paper. “He has a fine disposition, a good football brain and is an all-around gentleman on and off the field. He is just too fragile for the heavy going.”

Within two days, the papers announced that Caldwell would take a stab at professional hockey, having secured a tryout with the Providence Reds of the Canadian American Hockey League. But little is known about his tryout with the Reds.

One thing went right for Caldwell in 1928. He had put his $3,000 signing bonus from the Indians into radio stock and it had doubled in five weeks. He cashed out quickly.

Caldwell stuck with his plan to make it as an Indian, though it was clear that he wouldn’t be with the big club until his fielding improved.

On February 17, 1929, Caldwell signed with the new Haven Profs of the Eastern League. Aside from not being a major leaguer, he was sitting pretty. He had bought his parents a house in Ashton, putting $1,000 down and paying the mortgage at 6 percent. His equity in the stock market was over $25,000. Spring training in Norfolk, Virginia, was punctuated on April 8 by a 4-for-4 day against the Boston Braves, in which he hit two home runs, doubled, singled, and was intentionally walked with two on in the ninth inning, a pass that preserved a 13-12 Braves victory. During the season he played first base in all 155 of the team’s games. He batted .366 (10 percentage points behind the league batting champion) and had a .661 slugging average. His 214 hits included 29 doubles, 10 triples, and 41 home runs. The Profs finished in fifth place, 24½ games out of first.

The problem with Caldwell’s fielding remained. His 31 errors were more than any other team in the league made at the position. Meanwhile, in Cleveland, Lew Fonseca flashed the leather, making just eight errors at first base. Further solidifying his job against any Indians minor leaguer with ideas, Fonseca made 209 hits, led the American League with a .369 batting average and had 106 RBIs. The team as a whole improved, moving from seventh place in 1929 to third place in 1930. They had little need for the backfield hero.

Still, 1930 held hope. Caldwell had excelled as a batsman. He was pulling a paycheck as a professional athlete, paying his bills, and helping his parents. The New Haven Register reported on October 17 that he had purchased a home in the Valley Falls section of Cumberland for his parents. He continued to find ways to hustle a buck as a star athlete without accepting a job from a Yale classmate.

On November 1, 1929, the Register reported that he had formed the Bruce Caldwell All Star Football Team, made up of collegians from Yale, Syracuse, Villanova, Ohio State, Fordham, New York University, Purdue, Brown, California, Texas, Illinois, Rutgers, and Mississippi.

Caldwell had long stated that he would one day be a businessman, and the All Stars were strictly a business move. He had been wooed by the NFL’s Providence Steam Roller for 1929 but rejected the team’s offer as too little. Now he would harness the economic firepower of his fame, as did Ruth and Gehrig with their barnstorming teams, their Bustin’ Babes and Larrupin’ Lous. Caldwell set admission to see the All Stars at 75 cents, aggressive compared with the 50 cents for reserved seats and 15 cents for general admission charged by the New Haven Profs for a baseball game.

The handbills for the first game of the Caldwell All Stars touted Bruce as “Yale’s Greatest Football Star and All-American Player.” He ignored complaints that he was trying to capitalize on Yale’s name. He needed the money. The stock market crash of October 1929 had wiped out his $25,000 equity. He was broke and in debt.

The Caldwell All Stars barnstormed throughout Connecticut and Eastern League towns, rocking the gate and pummeling teams like the Bridgeport Westerns and the All Stamfords, elevens made of local semipros and police officers. Every game was preceded by an exhibition of punting and drop-kicking by the Bruiser. Every newspaper article about the All Stars sought to wring electricity out of Bruce’s Ivy League fame. By anyone’s estimates, the enterprise was well attended and thus profitable.

With that payday behind him, Caldwell signed on with the (New Haven) Williams semipro team of the Eastern Football League. He took a paycheck for one game against the Newark professional eleven at Savin Rock Park in New Haven on November 24, 1929.

In 1930 Caldwell went to spring training with the Indians hoping to displace Fonseca at first base. His Eastern League season had impressed the Indians management. They had signed him to a $700-a-month nonguaranteed contract. But before Opening Day the Indians sold him to Minneapolis of the American Association. With the Millers he found himself behind three talented first basemen, Hooks Cotter, 35-year-old High Pockets Kelly, who eventually was elected to the Hall of Fame, and Chick Tolson, another 35-year-old, who had five years in the major leagues. Type-cast and crowded out, Caldwell got just 24 at-bats in 10 games for Minneapolis, getting eight hits. But there just wasn’t room for him on the Millers. He was released in June, and the Indians also cut their ties with him. Caldwell signed with the Albany Senators of the Eastern League and batted .380 with 17 home runs, seven triples, 19 doubles, and a .642 slugging average in 321 at-bats. Though he found his Eastern League bat right where he had left it in 1929, he also found his glove right where he had left it, committing 19 errors.

As the 1930 season wrapped up, Caldwell was ready for his next autumnal fling at entrepreneurship. He opened a smoke shop near the Yale campus. He and two partners put only $200 in the venture, and sold $50,000 worth of stock to Yale fans eager to be associated with Bruisin’ Bruce. The New York Times ran a photo of Caldwell behind the smoke shop’s lunch counter, waiting on Smoky Joe Wood and William Hinchcliffe, Yale’s tennis coach. Meanwhile Caldwell looked for new worlds to conquer.

The New Haven Profs, the team for which Caldwell had a heavenly 1929 performance, was now defunct. Without Caldwell driving ticket sales in 1930, the team’s prospects flickered and went out. But on January 11, 1931, the New York Times reported that Caldwell and his former Profs manager, Gene Martin, had offered to buy the defunct franchise. Although Caldwell was still under contract with Albany, it was understood that the Senators would release him if the New Haven deal was consummated.

There were other hurdles to overcome. Caldwell wanted his team to play at Savin Rock Park, where the Profs had played; its private ownership allowed for the selling of profitable advertising signage, and the short left-field fence was tailor-made for his swing. But Savin Rock’s owner increased his asking price and the deal died. Caldwell next petitioned the mayor to lease him the town-owned Lighthouse Park, a diamond off the beaten path without on-site advertising opportunities. He assured the press and fans that pursuing Lighthouse was not a ruse to get the price for Savin Rock lowered. That was a sham. Price pressure was exactly what the savvy Caldwell was applying to the negotiation. The Savin Rock owner gave in and Caldwell soon signed a contract to play in the park of his choice.

There were three partners in the ownership group. Gene Martin was president, secretary, and field manager, in charge of baseball operations. David Fitzgerald, vice president, investor, and sportsman, was to be an adviser. Caldwell, treasurer, would handle public relations and play first base every day.

The Savin Rock field was renamed Donovan Field, in honor of Wild Bill Donovan, the manager of the 1922 New Haven Indians and 1923 New Haven Profs. Donovan, a major-league player and manager (he earned his nickname for his erratic control and fiery temper), had been a 25-game winner in both major leagues. In December 1923 Donovan was killed when the Twentieth Century Limited train from New York to Chicago was wrecked in Forsyth, New York. The team was renamed the Bulldogs – still a Yale reference.

Caldwell and his partners had saved baseball in New Haven. They agreed to pay the prior owner’s remaining debts, including player salaries from 1930. The $50,000 they raised by issuing stock put them in a good position to do so.

Being an owner agreed with Caldwell. Or at least it didn’t distract from his on-field performance. He had a year almost as good as in 1929, batting.356 with 26 doubles, 6 triples, 38 home runs, and a .666 slugging average. (On Memorial Day, May 30, his batting average was.606 and he had 17 home runs.) The Brooklyn Robins paid Caldwell $3,000 for the right to acquire his contract after the season (Martin and Fitzgerald received $25,000).

Where could Caldwell fit in Brooklyn? Del Bissonette was the incumbent at first base. Durable Del would play in the minors until he was 47 years old, but the Winthrop, Maine and High Pockets Kelly and Bud Clancy were waiting in the wings. Caldwell finished out the season in New Haven and prepared to earn some money playing semipro football in the fall. But that venture was short-lived. In October, playing for the “Caldwell All Stars,” he suffered a dislocated shoulder while making a tackle in the fourth quarter. Until then, the New Haven Register reported, he had been the “outstanding star of the game.”

Ledaving pro football reduced some of Caldwell’s income sources. But by that time, he was quietly putting himself on a new path. On January 13, 1931, the following note was entered into the records of the Yale Alumni Weekly: “Bruce Caldwell, Class of ’28, will enter into the Yale Law School in September.” And shortly after, he added another arrow to his quiver: “EX-GRID STAR A FIGHT MANAGER,” announced the headline in the January 12, 1932, New Haven Journal Courier. The paper carried an AP photo of Bruce with featherweight boxer Jimmy Quinn. The caption said, “Adding the prize ring to his list of ventures in the sports world, Bruce Caldwell … former Yale All-American football star, recently acquired the managership of Jimmie Quinn of Norwich, Conn. Quinn, a 126-pounder, has fought and won eight pro fights. Bruce is a restaurant owner, baseball player, ball club owner, football coach, and now a fight manager.”

It was a different Bruce pictured in the photo. Neatly dressed in suit and tie, arms spread wide, hands flat down on the corner ropes of a boxing ring, he looked serious and mature. A game-faced Quinn sat on a stool in front of him. Barechested and geared up to fight, Quinn faced the camera while Caldwell looked at him as if ready to tell him to keep moving, watch his flanks, and score with the left hook.

Quinn was strictly local talent. His matches were against other young men from Massachusetts and Connecticut, battles fought in Foot Guard Hall in Hartford and Valley Arena in Holyoke. He showed promise, winning his first eight bouts, all pre-Caldwell. He looked like a comer.

Caldwell sent the undefeated Quinn into the ring almost every month. Before June he fought Joey Izzo, Roland Lecuyer, Solly Ambrosio, and Johnny Bellus. He outpointed all except Izzo, who knocked him down in the process of winning a decision.

Law school and fight management kept Caldwell busy and sought to put money in his pocket during the bleakness of the Great Depression, which was in its second full year in 1932 and whose effects were being deeply felt in the US. Income, tax revenue, profits, and prices dropped, and international trade plunged by a half to two-thirds. Unemployment rose to 25 percent. Local economies that depended on heavy industry were hit hard.

The implication for leisure dollars was dire. The teams of the Eastern League, Caldwell’s New Haven Bulldogs included, were under financial pressure as they had also been in 1931. The Bulldogs, of which Caldwell was part owner and treasurer, still owed him part of his 1931 salary. If his partners, Gene Martin and David Fitzgerald, couldn’t come up with his pay for 1931, he would sit out 1932 and battle for his release so he could sign with a team that was able to pay him. That was exactly what happened: On May 19, the National Association of Baseball Leagues, the minors’ governing body, made Caldwell a free agent, allowing him to sign within any team in Organized Baseball. Two weeks later he was back in the flannels of a major-league team. After a tryout, he signed with the Brooklyn Robins.

Exactly where Caldwell would fit in with Brooklyn was a mystery. He couldn’t field any position but first base. His competition included his old Minneapolis teammate, High Pockets Kelly, plus Bud Clancy. Kelly made 10 errors in 621 chances at first that year for Brooklyn, newly rename the Dodgers. Clancy made two errors in 566 chances. Caldwell clanked it for two errors in just 16 chances for Brooklyn. The fielding bugaboo followed him until the end.

Caldwell’s first game as a Dodger was forgettable, the second was memorable. Manager Max Carey sent him in to replace Kelly early in the first game of a doubleheader against the Braves at Ebbets Field on May 29. Caldwell went 0-for-3 with one strikeout and an error at first. Caldwell was on the bench for the second game. The Dodgers were down 2-1 in the bottom of the ninth. Caldwell pinch-hit in the bottom of the ninth and drove in the tying run with a single. Then he scored the winner when Lefty O’Doul lined a walk-off single.

The joy was short-lived. Over the next eight days, a pattern emerged. Caldwell either pinch-hit and failed, or replaced Kelly at first early in the game while failing to get a hit or reach base in two or three tries. He was supposed to be an offensive threat and a defensive liability. In his second major-league tryout, he wasn’t really good at either. Caldwell’s fielding was costly in a June 3 one-run loss to the Braves at Ebbets Field. Third baseman Mickey Finn and Caldwell misplayed a pair of bunts in the ninth inning and allowed Boston to score the go-ahead run.

On June 15 the Dodgers optioned Caldwell to Hartford. He became a regular for the Senators, and in his first 29 games he drove in 21 runs though his batting average was just .230. Then the Depression hit home. On July 17 the Eastern League folded. Caldwell signed with Harrisburg, a Boston Braves farm team in the Class B New York-Pennsylvania League. In 35 games, Caldwell batted .360 in what was his last real stint in professional baseball.

The handwriting was almost on the wall. He was 27 years old now. He was a college football All-American, an NFL veteran, a baseball player with five years of professional experience, the owner of a minor-league Triple Crown, and the part owner of a minor-league team. A bright young man with a Yale education.

Caldwell’s public statements indicated that he was making the break from sports. He would move from athlete and entrepreneur to the world of mainstream employment. In the fall he entered law school.

The Register offered its analysis. “There is no doubt but that Bruce could retain a berth in the minor leagues for some years, but there is practically no chance of him winning a position in the majors, which has been his ambition. Bruce now realizes he is not a major-league performer, and he prefers to get into business as soon as possible rather than continue for an indefinite period in the minors.

Caldwell’s break from sports was not quite complete. The Register reported that Caldwell hoped to become a part-time assistant football coach for Yale while at Law school, as many others had done in the past. He also said he might play football with the semipro Connecticut Yankees. On October 16, in a game against a semipro team from Bloomfield, New Jersey, Caldwell was tackled on a running play, fell to the ground hard, and broke two ribs and dislocated his collarbone. It was Caldwell’s last beating on the gridiron, and his last paid athletic performance, though he still played from time to time in amateur baseball and football leagues. Participation in these low level but competitive leagues provided him with outlets to push his body, to recommit to the lessons of hard work, tenacity, and focus that had taught him to deal with the challenges of living.

Caldwell graduated from Yale Law School in 1935, passed the Connecticut bar examination (of the 37 other brand-new lawyers, 23 were Yale Law graduates). Almost immediately joined the law office of Thomas J. Spellacy, the mayor of Hartford. Spellacy appointed him commissioner of the Hartford Housing Authority, for which he oversaw a $10 million slum renewal project. In 1942, with the US at war, Caldwell joined the Navy and was in charge of recreation and entertainment on assignments in the US, the Pacific and South America. After the war he worked for Lockheed Aviation in Iceland. Back in New Haven in the early 1950s, Caldwell practiced law and for a time was the for New Haven Rent Control. In 1955 he was elected second selectman in West Haven and was appointed a judge in the West Haven Municipal Court.

Caldwell never married. He died on February 15, 1959, of cancer at the age of 54.

On December 10, 1938, the Saturday Evening Post published an article by Caldwell titled, “After the Ball Is Over.” The accompanying photos showed him running for Yale with a Jordanesque tongue sticking into the air, posed with his Indians manager, Roger Peckinpaugh, serving a shake in his smoke shop, then with his boxer, Jimmy Quinn, and in his Hartford law office.

The article was Caldwell’s answer to those who asserted that collegiate athletics impeded the development of students. The modest Cumberland boy explained what sports meant to him.

“I am convinced that if I had not learned to get up off the ground groggy and carry the ball in another try to gain in football, I never would have had what it took to tackle law school, to win my degree, and finally, to keep on hitting the line until I landed where I was determined to be. If it had not been for what I learned in athletics . . . I don’t believe I could have changed my course and have persevered on my new course until I reached my goal.”

Sources

’28 Decennial Classbook, Yale University, 1938.

Cohane, Tim. The Yale Football Story. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1951

Crawford, A.B., ed. Football Y Men 1920 to 1939, Vol. II. New Haven: Yale University, 1963.

Hartford Courant

New Haven Register

New Haven Journal Courier

New Orleans Times Picayune

New York Times

Saturday Evening Post, December 10, 1938

The Sporting News

Yale Daily News, April through June 1928

Baseball-Reference.com

Genealogybank.com

Retrosheet.org

Wikipedia.org

Yale alumni records

Yale University Library, Manuscripts and Archives

Full Name

Bruce Caldwell

Born

February 8, 1906 at Ashton, RI (USA)

Died

February 15, 1959 at West Haven, CT (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.