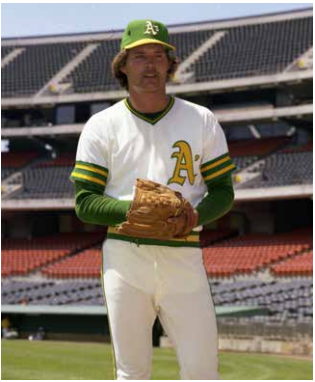

Brian Kingman

Pitcher Brian Kingman compiled an 8-20 record with the 1980 Oakland Athletics. Prior to 1980, instances of pitchers losing 20 games in a season occurred with great regularity. After Kingman’s 20-loss season, however, his place in baseball lore was cemented for 23 long years until it finally happened again. The stinging effects of Kingman’s 20-loss season contributed to the premature end of his once-promising big-league career, and also lingered for years in his post-baseball life. Over time, however, Kingman began to accept — and even embrace — his place in baseball infamy.

Pitcher Brian Kingman compiled an 8-20 record with the 1980 Oakland Athletics. Prior to 1980, instances of pitchers losing 20 games in a season occurred with great regularity. After Kingman’s 20-loss season, however, his place in baseball lore was cemented for 23 long years until it finally happened again. The stinging effects of Kingman’s 20-loss season contributed to the premature end of his once-promising big-league career, and also lingered for years in his post-baseball life. Over time, however, Kingman began to accept — and even embrace — his place in baseball infamy.

Brian Paul Kingman was born of English and German descent on July 27, 1953, in Los Angeles.1 His father, Paul, was an accountant, and his mother, Cecile, was a homemaker. Older siblings Dolores, Cordelia, and John rounded out the family. Kingman did not inherit his love for the game from his parents; neither his father nor his mother was a baseball fan.2 Instead, he traced his interest in baseball back to the first Los Angeles Dodgers game he attended as a child. He recalled, “Attending that game made a tremendous impression on me. It wasn’t just the game itself, it was being in the middle of 30,000 to 40,000 cheering people, mostly adults, who were invested in the outcome of the game.” From that initial experience, Kingman’s love for the game quickly blossomed. “My parents made me attend church every Sunday, but by the age of 9 or 10 I decided that baseball was my religion,” he once wrote. “Koufax and Drysdale might as well have been gods, and Vin Scully, the Dodgers radio voice the high priest. Each game was like a sermon.”3

Because of his father’s lack of interest in sports and relatively advanced age (Kingman was born when his father was in his mid-40s), Kingman was not afforded the opportunity to participate in organized baseball as a preteen. “It wasn’t a fit for [my father’s] schedule,” he explained.4 Baseball therefore had to wait until his teenage years. In addition to playing American Legion baseball for the West Los Angeles Post team, Kingman developed his skills on the University High School baseball team in Los Angeles. The Los Angeles City Section interscholastic league was highly competitive, helping to develop several future major-league stars during that era, including Eddie Murray, Ozzie Smith, and Robin Yount.5 The right-handed Kingman — who also played high-school football — excelled on the mound during his high-school senior year in 1971, posting a 1.89 ERA and being named to the All-Western Second Team.

After graduating from high school, Kingman continued both his education and baseball at Santa Barbara City College. His pitching talent did not go unnoticed while playing for the Vaqueros. On June 5, 1973, Kingman was drafted by the California Angels in the 12th round of the June Amateur Draft, but did not sign, choosing instead to remain in college. Upon attaining an associate degree, Kingman enrolled at the University of California, Santa Barbara. In addition to pursuing his bachelor’s degree he played varsity baseball for the Gauchos, and was fourth in strikeouts (38 in 49 innings) in the Pacific Coast Athletic Association in 1974. During the summer of ’74, Kingman continued to work at his pitching craft by playing for the semipro Calgary Jimmies of the former Alberta Major League. He was very effective for Calgary, leading the club to a championship in dramatic fashion by winning both games of a doubleheader. Although statistics for his season with the Jimmies are uncertain, it is believed that Kingman finished with an 8-2 record and nine complete games.6

The following year was an important one for Kingman both personally and professionally. On a personal level, he completed his studies at UCSB, attaining a bachelor’s degree in psychology and sociology. Shortly thereafter, Kingman became a professional baseball player when he was signed by Oakland Athletics scout Phil Pote as an amateur free agent on June 18, 1975. Oakland assigned him to the Boise A’s of the Class-A short-season Northwest League. Used primarily as a starter at Boise, Kingman had a solid first professional season, finishing the year 4-6 with a 3.89 ERA and five complete games. The highlight of Kingman’s inaugural minor-league campaign came on August 26, when the 6-foot-2, 200-pound hurler tossed a three-hit shutout with 11 strikeouts against the Eugene Emeralds — the only time the Northwest League-champion Emeralds were shut out all season.

Seeing promise in the 22-year-old, the Athletics promoted Kingman to the Double-A Chattanooga Lookouts of the Southern League in 1976. He spent the entire season in Chattanooga and excelled. On June 6 Kingman came within one out of a seven-inning no-hitter against Charlotte before having it broken up by a single. Reflecting on his strong start to the season, Kingman recalled, “I was 8-3 halfway through the season, had a moving fastball in the mid-90s, and good command of a sharp-breaking slider. If it weren’t for the fact that the A’s were a team with several established veteran pitchers, I would likely have been called up to the big leagues at that time.”7 He also ended the year in fine fashion, posting a 2.64 ERA while finishing second in the league in wins (14), fourth in innings pitched (184), and seventh in strikeouts (101). Kingman was a strong candidate for a September call-up to the big-league club when rosters were expanded, but tore a tendon in his elbow late in the minor-league season, ending any hopes he had of joining the Athletics.8

Based on his performance at Chattanooga, Kingman was promoted to the Triple-A San Jose Missions of the Pacific Coast League, where he spent the entire 1977 season. The elbow problems he suffered at the end of the prior season lingered throughout the year in San Jose, causing Kingman to miss eight weeks of the season. He remembered, “I spent a lot of time in doctors’ offices, getting cortisone shots and on the disabled list.” The injury adversely affected his performance on the mound. “I was no longer able to throw in the mid-90s, and there was no bite to my slider,” noted Kingman.9 In 16 appearances for the Missions (mostly as a starter), he finished the season with a disappointing 3-6 record and 7.80 ERA. Kingman underwent elbow surgery to repair the damage during the offseason.10

Unable to throw a ball until the following spring training after his successful surgery, Kingman found himself on the disabled list for the first nine weeks of the 1978 season. Although he rehabbed with Oakland’s Triple-A club in Vancouver, Kingman was sent to the Modesto A’s of the Class-A California League when he was finally able to take the mound in live games. Kingman admitted, “It was psychologically hard to find myself in A ball two years after being close to making the big leagues. Watching my teammates from Chattanooga move on to Triple A and the big leagues was hard as well. I felt like I was going backwards.”11 In addition to having to work hard to physically rehabilitate his injured elbow, Kingman also had to relearn to how to pitch. “I became a different pitcher by necessity. The velocity and movement on my fastball were diminished, and a curveball replaced my slider,” he recalled.12 Finding inspiration in the lyrics from the then-current hit song “Baker Street” by Gerry Rafferty, Kingman persevered through this difficult time, and ultimately found his form.13 Although he finished the season in Modesto with a modest 2-2 record in 10 appearances (nine as a starter), he boasted a 2.37 ERA with 43 strikeouts in 38 innings pitched.

After his bounce-back season in 1978, Oakland gave Kingman another chance at the Triple-A level for the 1979 season, this time with the Ogden A’s of the Pacific Coast League. At the same time as Kingman was carrying an impressive 7-2 record at Ogden into late June, the parent club in Oakland was mired in an awful season. With both injuries and poor performance plaguing their pitching, Oakland decided to call up the promising 25-year-old to bolster their struggling staff. On June 28, 1979, Kingman made his first major-league appearance, getting the start against the Royals in Kansas City. After some early jitters (he allowed three walks and had two wild pitches after two innings), he settled down, one-hitting the Royals into the sixth inning. He left the game after 5⅔ innings with a 5-4 lead, but ultimately received a no-decision. Kingman continued as a member of the Athletics’ starting rotation for the rest of the season, and had several notable moments along the way: He tossed a complete game against the California Angels in only his second big-league start, got his first big-league win in July at Yankee Stadium, and picked up his first big-league shutout in September against the Chicago White Sox. All told, Kingman showed great promise in his rookie campaign. After a three-hit complete-game victory against the Detroit Tigers in August, Tigers manager Sparky Anderson said of Kingman, “That kid had good stuff. I was told that the A’s had four or five good young pitchers and it’s obvious that he’s one of them.”14 Attributing his success to the new pitching approach he adopted while recovering from his elbow injury, Kingman explained, “I’m a pitcher instead of a thrower now.”15 He finished the year with five complete games and a 4.31 ERA in 18 appearances (17 starts). And aside from little-used teammate Alan Wirth, Kingman compiled the only winning record (8-7) on an Oakland team that finished the season with a dreadful 54-108 record. This juxtaposition was a harbinger of things to come for Kingman, though not in a positive way.

In an attempt to inject some life in his foundering club and improve its attractiveness for a potential sale, owner Charlie Finley hired fiery Billy Martin to manage the Athletics for the 1980 season.16 Martin quickly installed “Billy Ball” in Oakland, which was a demanding strategy that took advantage of speed, fundamentals, and an aggressive style of play. Martin’s Billy Ball also employed an aggressive approach to his pitching staff, which was returning all five of the primary starters from the prior season: Rick Langford, Mike Norris, Matt Keough, Steve McCatty, and Kingman. It was rumored that Martin’s longtime pitching coach, Art Fowler, recognizing the largely untapped talent in these young hurlers, immediately went to work to take the staff to the next level by instructing them in the finer points of throwing spitballs.17 Kingman later confirmed this, acknowledging, “Spitters? We were definitely throwing them. I know I tried a few.”18Along with pushing rules to the limits, Martin pushed his starters to their physical limits due to a suspect bullpen, expecting the starters to pitch deep into every game.19 The results of Martin’s unique approach were immediate and effective, with the Athletics rocketing to an early-season 16-9 first-place start in the American League West before cooling off.

Although Kingman did not enjoy quite the same success as his rotation mates from a wins-and-losses perspective as the season progressed, his 7-11 record in early August was not particularly concerning, especially considering that his ERA at the time was a solid 3.34. And the cerebral Kingman — noted for being an ardent chess player and a reader of scholarly materials while on road trips — was also considered by many to have had the best “stuff” of the Oakland starters. Despite this, things began to take a turn for the worse for Kingman. Losing his next eight consecutive starts to give him 19 with 13 games remaining on the schedule, Kingman had to cope with the real possibility of a 20-loss season. He also had to cope with the effects of a hostile manager Martin, whom he once called a “tyrant.”20

Dysfunction between the two had begun earlier in the season, when Kingman asked Martin for permission to get married during the All-Star break. Although Martin reluctantly allowed it, he did so while warning him to not let it affect his performance on the mound. Soon after marrying his wife, Diane (whom he had met in spring training in Arizona), Kingman began his extended losing streak. This provoked increasing ire from Martin, who was intolerant of losing. On several occasions, Martin was heard using foul language while vociferously castigating Kingman during visits to the mound.21 Kingman said, “The thing is, Billy likes to yell when he loses and I was losing the most and I don’t like to be yelled at.”22 Martin’s abrasive style coupled with the losing began to take its toll, with Kingman recalling, “Instead of looking forward to my next start, I began to dread it.”23

Shortly after Kingman’s 19th loss, despite their strained relationship, Martin sympathetically asked him if he wanted to avoid taking the mound in the final two weeks of the season. Kingman declined the offer. “I was a young player doing the macho thing. I was thinking, ‘What would he think if I said no?’ I didn’t want him to think I was a wimp,” Kingman later explained.24 On September 25 Kingman was inserted into a game against the White Sox in a relief role for the first time all season due to an injury to teammate Keough. Entering the game in the second inning, he pitched into the top of the eighth inning without allowing an earned run. With the score tied 4-4, Kingman loaded the bases on his first three batters in the eighth, and was removed from the game. His replacement on the mound, Dave Beard, allowed the White Sox to take a 6-4 lead after two inherited runners scored on a single by Mike Squires that proved to be the game-winner. Although Kingman allowed only two earned runs in his 5⅔ innings of work, he was tagged with his 20th loss of the season. He appeared in two more games before the end of the season, picking up a win in a start against the White Sox and narrowly avoiding another loss in an unexpected relief role in extra innings against the Milwaukee Brewers in Oakland’s final game of the year (while hungover from a celebration of the team’s last road game of the season the night before).25 Kingman finished the 1980 season with an 8-20 record, making him the most recent 20-game loser, replacing Phil Niekro, who had lost 20 a year earlier. With Oakland finishing the season at 83-79, Kingman became the first 20-game loser on a winning team since 1922.

Statistically, the 20 losses could be largely attributed to a hard-luck year for Kingman. His 3.83 ERA and 1.38 WHIP were both lower than league average and strikingly similar to those of fellow rotation member McCatty, who finished the season with a 14-14 record. Additionally, Kingman’s ERA was nearly identical to that of 1980 20-game winner Dennis Leonard of the Kansas City Royals. Perhaps most revealing, Oakland scored a paltry average of 2.87 runs in Kingman’s starts — in stark contrast to the 4.55-per-game run support the other Oakland starters received that season — and scored three runs or less in 70 percent of his starts, including five shutouts. And excluding an anomalous start in late April in which the A’s scored 11 runs, Kingman’s run support dropped to an even more meager 2.59 per game.

Despite his difficult 1980 season, Kingman found himself back in the Athletics’ same starting rotation — dubbed the Five Aces — at the beginning of the 1981 campaign.26 The team started the season with an impressive 11-0 record, with Kingman also performing well in the early going. He allowed only two earned runs in his first 22⅓ innings, and eventually carried a fine 2.72 ERA after 11 starts into the June baseball strike. Once play resumed in August, however, Kingman was sent “sulking” to the bullpen by his “nemesis” Martin after a couple of shaky starts, further aggravating their already poor relationship.27 He regressed from that point, finishing the season with a 3-6 record in 18 games (15 starts) and an ERA that had ballooned to 3.95. And although Oakland advanced past the AL Division Series and into the AL Championship Series, Kingman saw action in only one postseason game, pitching poorly in a brief relief stint in a 13-3 ALCS loss to the New York Yankees.

After struggling in spring training in 1982, Kingman was assigned to the Tacoma Tigers of the Triple-A Pacific Coast League to start the season to keep sharp until manager Martin converted from a four- to a five-man rotation. After originally refusing to report to Tacoma and asking to be traded, Kingman relented, and pitched reasonably well there in eight starts.28 He was recalled in June; however, the lingering effects of the demotion to Tacoma caused further crumbling of Kingman’s relationship with Martin. This manifested itself in a late-night altercation between the two outside a Kansas City hotel while on a late-June road trip.29 Although Kingman’s roster position with the big-league club survived this ugly incident, his performance on the mound suffered. Kingman finished the season with a 4-12 record and a 4.48 ERA in 23 games (20 starts).

Kingman got a much-needed change of scenery in 1983, when he was traded to Boston in January, acquired on the recommendation of Red Sox pitching coach Lee Stange, who worked with him while in the Athletics organization. “He can pitch,” Stange said. “He has an exceptional curveball, as good as anyone here. He got into trouble in Oakland, but it wasn’t entirely his fault. He didn’t get along with Billy [Martin] and lost some of his confidence.”30 After accepting an assignment to the Red Sox’ Triple-A affiliate in Pawtucket, however, Kingman was released in a cash-saving move before the regular season.31 In May he was signed as a free agent by the San Francisco Giants and assigned to the Phoenix Giants of the Pacific Coast League. After starting the season in Phoenix with a 2-0 record, Kingman joined the big-league club in June.32 Upon compiling a 7.71 ERA and 2.36 WHIP in three games with San Francisco, he was sent back to Phoenix, where he finished out the season with a 6-6 record and a 5.53 ERA in 25 games (14 starts).

Kingman was back with Phoenix for the entire 1984 season, pitching primarily out of the bullpen. Although he finished the year with an innocuous 5-5 record in 30 games, Kingman nursed lower-back injuries and posted a disappointing 6.37 ERA and 1.71 WHIP. 33 Hating the game and unwilling to continue fighting the ever-present “loser label,” Kingman retired from professional baseball at age 31. “A stigma is hard to get rid of in baseball,” opined former Oakland rotation mate Keough of Kingman’s situation. “We are not a fast traveling business. We give labels, and they stick.”34

Kingman settled in Phoenix. He began selling real estate, and then soon found more permanent employment working for a check-cashing company to help support his wife, Diane, and two young sons, Matthew and Alex.35 It was here in 1992 that Kingman — disgruntled after not receiving a desired promotion — got caught and convicted of a phony check-cashing scheme against his employer, wiping out his assets and causing him to struggle to pay the bills by delivering newspapers and managing a convenience store.36 Another misstep occurred later in that same year, when Kingman — facilitating dealings between an art broker friend and a father-son team from Las Vegas who possessed a Picasso painting — was arrested by the FBI for trafficking in stolen art in a “sting operation too hokey for a TV movie of the week.”37 Although the federal charges were dropped in the convoluted case when the painting was found to be bogus, Kingman was sentenced to 60 days in county jail, all the while maintaining his innocence. “I still think it was the silliest case I’d ever heard of,” he said.38 Kingman rebounded from these troubles, however, and eventually became the owner of a financial-services business. As of 2016 he worked for a regional distribution company, and has found the game once again, after previously thinking that “he had enough of baseball.”39 After not having thrown a ball for nearly a quarter-century, in the late 2000s Kingman was persuaded by former high-school and college teammates to join the Arizona Men’s Senior Baseball League, where he “rediscovered the joyful innocence of playing baseball.”40 He was still playing in the league as of 2016, even after battling through two knee replacements.41

The negative effects of being a 20-game loser lingered with Kingman for years after he left the game, especially after the passing of each season with no pitcher matching that total. He resorted to packing away the memorabilia from his baseball career. “It brought back bad memories. For five years I didn’t look at it. It was too painful,” Kingman explained.42 Even his children had to deal with classmates calling their father “a loser.”43 However, as his research revealed the good company he was in as a 20-game loser (the list includes numerous Hall of Famers, Cy Young Award winners, and All-Stars), Kingman began to come to terms with his place in history — even embracing it. “At the time I took it real hard. There is no question it shortened my career. But my feelings have changed 360 degrees,” he said.44 “At least I’ve been able to take something that once caused me pain and actually come to enjoy it. If we can do that with all kinds of things in life, think how much better off we’d all be. If you can have fun with something that caused you pain, it means you’ve conquered it.”45 As other pitchers approached possible 20th losses over the years, Kingman began employing a voodoo doll in an attempt to prevent his infamous feat from being overtaken. “Right now I’m the answer to a trivia question. But whenever anyone loses 19, I’m on trivia death row,” he once quipped.46 On September 5, 2003, however, Kingman’s 23-year run as “The Last of the 20-Game Losers” ended as Detroit Tiger Mike Maroth suffered his 20th defeat of the season in an 8-6 loss to the Toronto Blue Jays. Upon having his place taken in the annals of baseball, the witty and self-deprecating Kingman commented, “Maybe I’ll get a shot to make a comeback next year.”47

Last revised: July 1, 2017

This biography is included in “20-Game Losers” (SABR, 2017), edited by Bill Nowlin and Emmet R. Nowlin.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Brian Kingman and Gary Trujillo for their research assistance.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author accessed Kingman’s file from the library of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, New York; Ancestry.com; Baseball-Reference.com; Newspapers.com; and Retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 Although Kingman’s birth year is popularly reported as 1954, he was in fact born in 1953 as confirmed by State of California birth records and Kingman himself in email correspondence with the author on June 15, 2017.

2 Brian Kingman, email correspondence with author, November 22, 2016.

3 Brian Kingman, “The Love of Baseball — From the Eyes of an 8-Year-Old Through Sandy Koufax to the Major Leagues,” Arizona Men’s Senior Baseball League Newsletter, Issue 2.

4 Kingman email correspondence, November 22, 2016.

5 CIF Los Angeles City Section, “Notable Alumni,” https://cif-la.org/apps/pages/index.jsp?uREC_ID=49068&type=d&pREC_ID=119529, accessed November 17, 2016.

6 Jay-Dell Mah, Western Canada Baseball, “Major Leaguers & Western Canada Baseball,” https://attheplate.com/wcbl/majorleaguers_2.html, accessed November 17, 2016.

7 “The Love of Baseball.”

8 Ibid.

9 Gary Trujillo, Coco Crisp’s Afro, “Brian Kingman Interview Part 1… The Minor Leagues,” https://cococrispafro.wordpress.com/2014/04/03/brian-kingman-interview-part-1-the-minor-leagues/, accessed November 17, 2016.

10 Associated Press, “Rookie Right-Hander Doesn’t Miss Plate,” Santa Cruz Sentinel, August 22, 1979.

11 “Brian Kingman Interview Part 1.”

12 “The Love of Baseball.”

13 “Brian Kingman Interview Part 1.”

14 “Rookie Right-Hander Doesn’t Miss Plate.”

15 Ibid.

16 G. Michael Green and Roger D. Launius, Charlie Finley: The Outrageous Story of Baseball’s Super Showman (New York: Walker Publishing Company, 2010), 290-292.

17 Bill Pennington, Billy Martin: Baseball’s Flawed Genius (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2015), 354.

18 Ron Fimrite, “Whatever Happened to the Class of ’81?” Sports Illustrated, September 10, 1984.

19 Ibid.

20 Ibid.

21 Nancy Finley, Finley Ball: How Two Baseball Outsiders Turned the Oakland A’s Into a Dynasty and Changed the Game Forever (Washington: Regnery History, 2016), 209.

22 “Whatever Happened To The Class Of ’81?”

23 Gary Trujillo, Coco Crisp’s Afro, “Brian Kingman Talks About His Career and His Troubles With Billy Martin.”

24 Mel Antonen, “Kingman May Lose Distinction as Loser,” USA Today, August 25, 2003.

25 Gary Trujillo, Coco Crisp’s Afro, “Brian Kingman Interview… Part 4,” https://cococrispafro.wordpress.com/2014/04/19/brian-kingman-interview-part4/, accessed November 17, 2016.

26 “The Amazing A’s and Their Five Aces,” Sports Illustrated, April 27, 1981.

27 “Whatever Happened to the Class of ’81?”

28 United Press International, “Brian Kingman Can Relax Now. When You Are Pitching Well …” July 7, 1982, https://upi.com/Archives/1982/07/07/Brian-Kingman-can-relax-nowWhen-you-are-pitching-well/1060394862400/, accessed November 17, 2016.

29 Associated Press, “Oakland A’s in Turmoil,” Greenville (South Carolina) News, July 6, 1982.

30 Associated Press, “Kingman Welcomes Shot With Red Sox,” Galveston Daily News, February 28, 1983.

31 David Fink, “Sports Briefing,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, March 28, 1983.

32 Associated Press, “Giants Not Pretty but Still Win,” Santa Cruz Sentinel, June 2, 1983.

33 Bob Cohn, “Lackluster Phoenix Felled by Edmonton,” Arizona Republic, July 12, 1984.

34 “Kingman May Lose Distinction as Loser.”

35 Ibid.

36 Michael Kiefer, “Brian Kingman’s Blue Period,” Phoenix New Times, July 7, 1994.

37 Ibid.

38 Thomas McShane and Dary Matera, Stolen Masterpiece Tracker: The Dangerous Life of the FBI’s #1 Art Sleuth (Fort Lee, New Jersey: Barricade Books, 2006), 234-248; Michael Kiefer, “Take Me Out to the Exercise Yard: Netted in a Stolen-Art Sting, Brian Kingman Goes From the Big Leagues to Big House,” Phoenix New Times, December 8, 1994.

39 Britten Gerrard, MSBLNational.com, “Kingman, Cripe Still Playing After All These Years,” https://msblnational.com/TOR-Desert-Classic-Entry/Blog/2013-Desert-Classic-a-Huge-Success.htm, accessed November 17, 2016.

40 “The Love of Baseball.”

41 Kingman email correspondence, November 22, 2016.

42 “Kingman May Lose Distinction as Loser.”

43 Jeffrey Zaslow, “Lessons From Some Losers: Detroit Tigers Are Moving On,” Wall Street Journal, September 30, 2003.

44 Jerome Holtzman, The Jerome Holtzman Baseball Reader (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2003), 4. At times people come up with expressions that should not be taken too literally.

45 Jayson Stark, “’King’ Won’t Be Forgotten,” ESPN.com, https://espn.com/mlb/columns/story?id=1611581&columnist=stark_jayson, accessed November 17, 2016.

46 Glenn Kaplan, “Brian Kingman, Pitcher,” Sports Illustrated, October 7, 2002.

47 “’King’ Won’t Be Forgotten.”

Full Name

Brian Paul Kingman

Born

July 27, 1953 at Los Angeles, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.