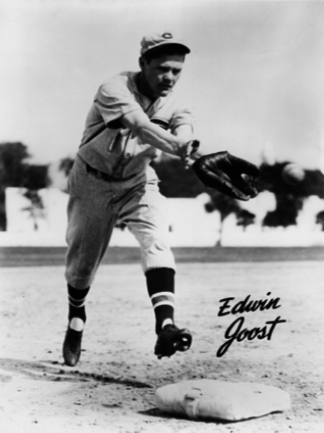

Eddie Joost

One thing about Eddie Joost — he learned how to work a walk. A lifetime .239 hitter over the course of 17 major-league seasons, Joost drew more than 1,000 bases on balls—enough to give him a very good on-base percentage of .361. He hit safely 1,339 times, but reached base via the walk or hit-by-pitch 1,076 times.

One thing about Eddie Joost — he learned how to work a walk. A lifetime .239 hitter over the course of 17 major-league seasons, Joost drew more than 1,000 bases on balls—enough to give him a very good on-base percentage of .361. He hit safely 1,339 times, but reached base via the walk or hit-by-pitch 1,076 times.

He was a two-time All-Star and earned some distinction as the last manager in Philadelphia Athletics history, and only the third one the team had in its 54 years before the franchise moved west to Kansas City.

Joost was born to Emma C. Joost and her husband, Henry, an auto mechanic, on June 5, 1916, in San Francisco. He was the second of five children born to the couple. Emma’s parents were both native Californians; Henry’s both came from Germany. Henry Joost had played some semipro baseball.[fn] Philadelphia Athletics 1948 press release in Joost’s Hall of Fame player file. See also The Sporting News, June 22, 1949. Henry Joost had been a catcher. [/fn] His son Edwin David Joost considered himself of German/Dutch ancestry.

Life in the days of the Depression was not easy. “My family wasn’t destitute,” Joost said, “but it was close to it.” [fn]Eric Ahlqvist, “Joost still has lots of juice,” Cooperstown Crier, August 14, 2008. [/fn] Eddie attended Bryant Elementary School and Horace Mann Junior High, and then graduated from Mission High School, all in San Francisco. He started playing professional baseball early, signing with the Mission Reds of the Pacific Coast League at the age of 16, while still in high school, for $150 a month.[fn] San Francisco Examiner, February 24, 1991. [/fn] The team played at Seals Stadium in San Francisco and Eddie’s first season was in 1933 under manager Fred Hofmann. He played as a shortstop, appeared in 25 games, and hit .250. He played with the Mission Reds for four seasons, through 1936 and was the team’s principal third baseman in 1935 and 1936, batting .287 and .286 respectively under managers Gabby Street and Willie Kamm.

Joost’s contract was sold to the Cincinnati Reds near the end of the 1936 season, and he was a September call-up to the majors. He got into 13 games for manager Chuck Dressen, going 4-for-26 with just one run batted in and one extra-base hit, a double. Nonetheless, he’d gotten his feet wet.

Dressen wasn’t all that impressed. Joost later recalled his manager telling him, “What I have seen of you, you will not be a major-league player. … If we keep you, you’ll be a utility player.” [fn] Handwritten notes by Eddie Joost in his player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, and Rich Marazzi, “Joost spins a tale of two careers,” Sports Collectors Digest, July 2, 1999. [/fn]

Joost played for Cincinnati’s Syracuse Chiefs affiliate in the International League in 1937, hitting .269 in what was then Double-A ball, and then coming back to the majors (and going 1-for-12) in September.

On October 16, 1937, Eddie married Alice Bernard; the two had met in high school. They had the first of their five sons in September 1939, but lost Edwin Jr. to leukemia in November 1941. The four younger Joosts were David, Dennis, Donald, and Dean.

In 1938 Joost played for the Kansas City Blues, the New York Yankees’ farm team in the American Association. He hit .289 for them, with five homers. Though runners-up in the American Association, the Blues beat the Newark Bears and won the Junior World Series in seven games.

From 1939 through 1943, Joost was back in the majors, and with the Reds for the first four of those years, all under Bill McKechnie. He began as a utility infielder. Joost had never been on a pennant-winning team in the minors (though winning the Junior World Series was at least as good), but won back-to-back pennants with Cincinnati in 1939 and 1940, the Reds’ world championship season. He appeared in only 42 games in ’39 (batting .252), but he played in 88 games in ’40, batting .216 while drawing enough walks to bump his on-base percentage up to just over .300. He had a very good .960 fielding percentage. He hit the first of his 134 major-league home runs on June 17, 1940, off BoomBoom Beck of the Phillies. Following tradition, his teammates pointedly ignored the homer, so when Joost got back on the bench, he loudly applauded for himself.

Joost didn’t play in the 1939 World Series, as the Reds were swept by the Yankees. In 1940 he played in all seven games as the team’s second baseman. It was his only postseason action. He was 5-for-25 with two RBIs, knocking in the first Reds run in Game Two, a 5-3 victory. The Reds went on to beat the Tigers.

Joost got the opportunity only because an accident had befallen the Reds’ regular second baseman, Lonny Frey. A couple of days before the Series, Frey had stopped to get a drink from the dugout water cooler and the heavy iron cover fell on his foot and broke some of his toes. Joost acquitted himself well and in December McKechnie said, “Whoever plays shortstop for the Reds next year will have to beat out Eddie Joost.” [fn] Cincinnati Reds press release, December 1940, from Joost’s Hall of Fame player file. [/fn]

When McKechnie greeted Joost the following spring, he congratulated him again on the World Series win. Joost shot back, “If you had played me in the 1939 Series we would have won that one, too.” Joost later admitted it wasn’t the most tactful thing to say. “Not a great start for the ’41 season.” [fn] Joost’s handwritten notes in his player file. A couple of the brief quotations that follow are Joost’s, from these notes. [/fn]

Joost had what was described as “a prickly personality, an aggressive style and strong opinions that often didn’t sit too well with the martinets who ran big-league teams at the time.”[fn]San Francisco Examiner, February 24, 1991[/fn] He clashed more than once with McKechnie and, later, Casey Stengel. Though he allowed that McKechnie was “a good manager,” he also said that “occasionally he was wrong and sometimes I would tell him that. The next thing you know he and I just didn’t get along.” It may have factored into his later trade to the Boston Braves. [fn] Sports Collectors Digest, July 2, 1999.[/fn] McKechnie, for his part, seemed to have warm enough feelings for Joost. [fn]Christian Science Monitor, August 9, 1943.[/fn]

There had been some thought that Joost was too slight (he grew to 6-feet even and eventually added 15 pounds to fill out to 175 pounds) and lacked the stamina for regular play; he was sometimes called “The Thin Man.” His minor-league record should have disproved that, but his work over the next couple of years finally put the notion to rest.

Joost played almost every game in both 1941 and 1942, batting .253 (.340 OBP) and .224 (.307). He tied a major-league record in the May 7, 1941, game, successfully handling 19 chances at shortstop (he also made an error). The team finished in third place, then fourth place, and in December 1942 (“not a year to brag about”) the club traded Joost and pitcher Nate Andrews (and $25,000) to the Braves to acquire shortstop Eddie Miller, who was coming off three All-Star seasons and would go on to four more. Boston sportswriter Al Hirshberg wrote that Alice Joost had wanted to leave Cincinnati, that she couldn’t bear to return after the loss of their child there.[fn]Unidentified article in Joost’s Hall of Fame player file.[/fn] McKechnie was said to understand and helped facilitate the change of scenery.[fn]Hartford Courant, December 9, 1943 .[/fn]

Joost was a “sparkplug” early in the season, bringing some fresh competitive fire to the Braves, but cooled off soon. He played in 124 games for the Braves, but hit only .185—though his 68 bases on balls lifted his OBP to .299. An August article in the Christian Science Monitor talked about a real change of demeanor in Joost during the season.[fn]Christian Science Monitor, August 9, 1943.[/fn] Manager Casey Stengel seemed to very much rub him the wrong way.

Joost missed all of 1944 due to World War II, although he didn’t serve in the war. Though initially rejected by the Army, he passed the second time around and was told by the draft board that he had to do defense work in a meat-packing plant as part of the war effort, or be inducted. One sportswriter characterized the work as “heaving hams in a San Francisco slaughterhouse.”[fn]Roger Birtwell in the Boston Globe, April 6, 1945[/fn] He played some industrial league ball on Sundays.

Joost did not get along with Stengel and later called him “one of the worst managers in baseball at the time.” [fn]Ibid.[/fn] When Stengel was giving a talk before a game, Joost admitted, he would turn his chair away from his manager and read a newspaper. In turn, there was at least one time that Stengel changed the signs for his third-base coach but pointedly told the coach not to let Joost know they had changed. [fn]Cooperstown Crier, August 14, 2008.[/fn] Joost acknowledged that he didn’t play well at all for the Braves.

Joost excelled in spring training and played for the Braves again in 1945, hitting .248 through July 19. But on that date he suffered a broken wrist when Billy Jurges slid into third base, kicked at his glove, and hit his wrist instead. He thought he had permission to return home after the injury but may have left the Braves without the proper formalities, and he was declared AWOL and suspended on August 22. “Not a good year. Enough said.”

Commissioner Happy Chandler got involved in the dispute regarding Joost’s departure from the Braves, and in February 1946 Boston made a deal with the St. Louis Cardinals for Johnny Hopp, giving Joost his outright release to Rochester, the Triple-A International League club of the Cardinals, and sending St. Louis $40,000. Joost initially said he would not report. There had been four clubs that claimed him when the Braves placed him on waivers, and he thought he could still play major-league ball.[fn]Los Angeles Times, February 7, 1946[/fn] In the end, Joost did report and had a very good year. He hit 19 homers—more than all his prior years in the minors combined—and batted .276, driving in 101 runs.

The Philadelphia Athletics were interested—the only team that was – and invested $10,000 (and three players) to purchase Joost’s contract at the end of September. Connie Mack reportedly told him, “I’ve heard good reports and bad reports about you, young man. I believe the good ones.” [fn]San Francisco Examiner, February 24, 1991.[/fn] One of the bad stories was detailed in The Sporting News, something of a guilt-by-association incident that led many in baseball to think Joost had a problem with alcohol. “I’m a highstrung sort of guy,” Joost said, “and beer relieves the tension. But I never was drunk in my life.” [fn]The Sporting News, May 26, 1948.[/fn]

Joost said that Mack “was a great man, a great person. I don’t think in the eight years I was with the A’s I ever heard him say an unkind word to anyone.”[fn]Ibid.[/fn]

It proved a good investment for Philadelphia, though Joost’s first year with the A’s, 1947, was not that successful; he struck out a league-leading 110 times and batted only .206. “I had astigmatism,” Joost said in 1994, “but I didn’t want Mr. Mack to know it because only [one big-league player] wore glasses. But it got worse. … I finally got up the nerve to tell Mr. Mack that I’d probably have to wear glasses.”[fn]Philadelphia Inquirer, April 14, 2011.[/fn] He did, for the rest of his career, and his average jumped back up to .250 (.393 OBP) the following year.

Joost did have his home-run stroke going, though, with 13 in 1947—and his 24 sacrifice hits led the league. It was more than double the number of successful sacrifices in any other year; perhaps he felt more comfortable putting down bunts than swinging away.

Joost spent eight seasons in Philadelphia and was the team’s starting shortstop for the first six of those years, 1947 through 1952. He was solid in the field, and during one stretch from late 1947 into June 1948, he played 42 straight error-free games at shortstop, and handled 225 consecutive errorless chances, both records at the time. At least one publication called him a “pepperpot with specs.” [fn]Unidentified article in Joost’s Hall of Fame player file.[/fn] Shirley Povich of the Washington Post wrote that Joost “has been the making of the A’s infield.” [fn]Shirley Povich, Washington Post, May 7, 1948.[/fn]

Joost hit .249 over his eight Athletics seasons but was so patient at the plate that he recorded an on-base percentage of .392. He drew an average of 118 walks per season in the six full seasons he played for the A’s. Twice he scored over 100 runs and twice he was in the 90s. His best season was probably 1949, when he hit .263 and got on base at a .429 pace. He drove in a career-high 81 runs (from the leadoff spot) and scored a career-high 128 runs. He was named to the All-Star squad and came in 13th in MVP voting. He and second baseman Pete Suder helped the team turn a record 217 double plays.

In the 1949 All-Star Game, Joost singled to drive in two runs and help the American League win, 11-7. He called it “the greatest single I ever hit in my life. I was so proud to be in the game.” [fn]USports Collectors Digest, July 2, 1999.[/fn]

Joost had picked up some power, too, after the wartime work in the meat-packing plant and his year in Rochester. He averaged just over 18 home runs a year in his first six seasons with the Athletics, with a careerhigh 23 homers in 1949, starting with a home run to help win the home opener. He hit two homers on his 26 birthday, June 5—“the first man ever to bash two homers off the distant left-field [Cleveland Stadium] girders in one game.” [fn]The Sporting News, June 22, 1949. [/fn] He’d actually hit one in each game of a doubleheader, against two future Hall of Famers, Bob Feller and Satchel Paige. The homers came early in the year—15 by mid-June. From July 26 on, he hit only two, both in September. Joost’s fielding was fairly consistent from year to year, and he wound up with a .956 career fielding percentage.

“During the late 1940s,” the Philadelphia Inquirer wrote, “Mr. Joost helped the A’s achieve one last run of respectability in Philadelphia.” After finishing last nine times between 1935 and 1946, they reached the first division—fourth place—in 1948 and 1952, and set an all-time attendance mark in 1947 and then again in 1948. Joost “nearly saved the Philadelphia A’s as their spark-plug shortstop,” wrote the Inquirer in its obituary.[fn] Philadelphia Inquirer, April 14, 2011.[/fn]He was a fan favorite; a late-season poll of Philadelphia Bulletin readers ranked him as the Athletics’ most valuable player.[fn]As reported by the Associated Press on September 11, 1948.[/fn] Three days later, Joost had five consecutive hits and scored four runs in a 12-2 win over the St. Louis Browns.

Joost’s desire to get into games was exemplified in August 1948 when he suffered a jammed thumb and missed a week of games. He was hospitalized for treatment, but worked out an arrangement that allowed him to check out long enough to play in home games but then return to the hospital overnight for further treatment.[fn] New York Times, August 20, 1948.[/fn]It was a couple of weeks later that an amusing incident occurred. Billy Goodman of the Red Sox hit a ball to Joost at shortstop—and the ball disappeared. He looked around for it in vain, and then undid his shirt—the ball had rolled up his arm and entered his sleeve and fallen inside his jersey.

In five seasons from 1947 through 1952, excepting only 1950, Joost placed in the top 15 in the voting for American League MVP. Though he never ranked higher than tenth place (1948), his vote totals nonetheless constituted recognition of his excellence. His best day overall was likely June 16, 1951, when he broke out of an 0-for-16 slump and hit two home runs and a game-winning 11th-inning triple. It wasn’t uncommon for people to compare his play with that of Phil Rizzuto. And Casey Stengel, Rizzuto’s manager with the Yankees, “pointed to a slim, bespectacled guy who looks more like an accountant than a shortstop and commented, ‘There, fellows, is a mighty fine ballplayer.’”[fn]Hartford Courant, August 16, 1951.[/fn]

Joost had an appendectomy in February 1953. A serious injury to his right knee brought his 1953 season to an end after the game on June 19. (He hurt the same knee in an automobile crash the following January.) He appeared in only 51 games in 1953, batting .249. In one of those games, on May 10 against the Washington Senators, his was the only base hit of the game for the Athletics. It was—bizarrely—the third time Bob Porterfield was deprived of a no-hitter on a base hit coming in the seventh inning.

Joost didn’t play as much in 1954 (19 scattered games, but with a .362 batting average when he did appear) because in November 1953 he was named manager of the team. Connie Mack had managed through 1950 (he’d managed the team since 1901), and Jimmie Dykes from 1951-53. The team apparently did not think “a manager should play 18 holes of golf every day and come into the clubhouse all tired out. We needed a change, some younger blood at the helm.”[fn]The Sporting News, Novemer 11, 1953.[/fn]Dykes finished in seventh place in 1953, with 95 losses. Joost had been expected to be a playing manager but the car crash in January left him feeling he’d do better to stick to managing.

Joost hadn’t wanted to be manager, Dick Rosen told the Philadelphia Daily News. “Rosen said he was told by Spook Jacobs, who played for the Athletics in the mid-1950s, that Joost was named manager because the Athletics simply took the highest-paid player and promoted him to save money. ‘They gave him added duties without giving him added salary. They were financially down. … He didn’t want to be the manager, he had to be the manager.”[fn]Philadelphia Daily News, April 14, 2011.[/fn] His salary that year was the most he ever earned, $30,000.[fn]San Francisco Examiner, Febuary, 24, 1991.[/fn]One of his coaches was former Negro League star Judy Johnson, the first African American coach in major-league history. Unfortunately, the Athletics lost 103 games and ended up in last place.

In 1955 the franchise moved to Kansas City and Lou Boudreau became the manager. Joost was not part of the sale and was released in November 1954 by the relocated and renamed team. He tried out with Cleveland during spring training, and was offered a contract but he had kept in touch with old friend Joe Cronin, the GM of the Boston Red Sox. At the end of March 1955, the Red Sox signed Joost to fill in for the injured Milt Bolling. He played well in spring training, hitting .340, and made the team, but it was an engagement that lasted just the one season; he was released on October 3. He suffered two broken bones when he was hit on the left hand in late April and lost playing time. He played shortstop and second base, appearing in 55 games over the course of the year, batting .193 and yet again reaching base nearly 30 percent of the time (.299 OBP). It was his last season in the majors.

In December Cronin asked Joost (both of them native San Franciscans) to manage and play for the Red Sox-affiliated San Francisco Seals in 1956. He was managing a few years after the immensely popular Lefty O’Doul and those were hard shoes to fill. Joost played in only six games, and the team underperformed in the early going. On June 9 he was replaced by Joe Gordon. It was his final year as either player or manager in Organized Baseball. Though he’d said he wanted to stay in the game, Joost did not. Instead he took up work as an automobile salesman in San Francisco, and later opened a sportswear shop in nearby Burlingame. In 1961 he told an inquiring reporter that he’d go right back to work in baseball if someone were to call and offer him another opportunity to manage. [fn]Hartford Courant .[/fn]Eddie’s son Dean Joost played three years of minorleague ball in the Athletics, Angels, and Indians systems, from 1970-72, never rising about Single-A. He was a third baseman who played a few games in the outfield.

Joost remained very popular with A’s fans from Philly days and attended Philadelphia Athletics Historical Society events as late as 2009.

Joost died during his sleep on April 12, 2011, in Shingle Springs, near Fair Oaks, California, at the age of 94.

Last revised: July 12, 2021 (zp)

This biography originally appeared in “Van Lingle Mungo: The Man, The Song, The Players” (SABR, 2014), edited by Bill Nowlin.

Full Name

Edwin David Joost

Born

June 5, 1916 at San Francisco, CA (USA)

Died

April 12, 2011 at Fair Oaks, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.