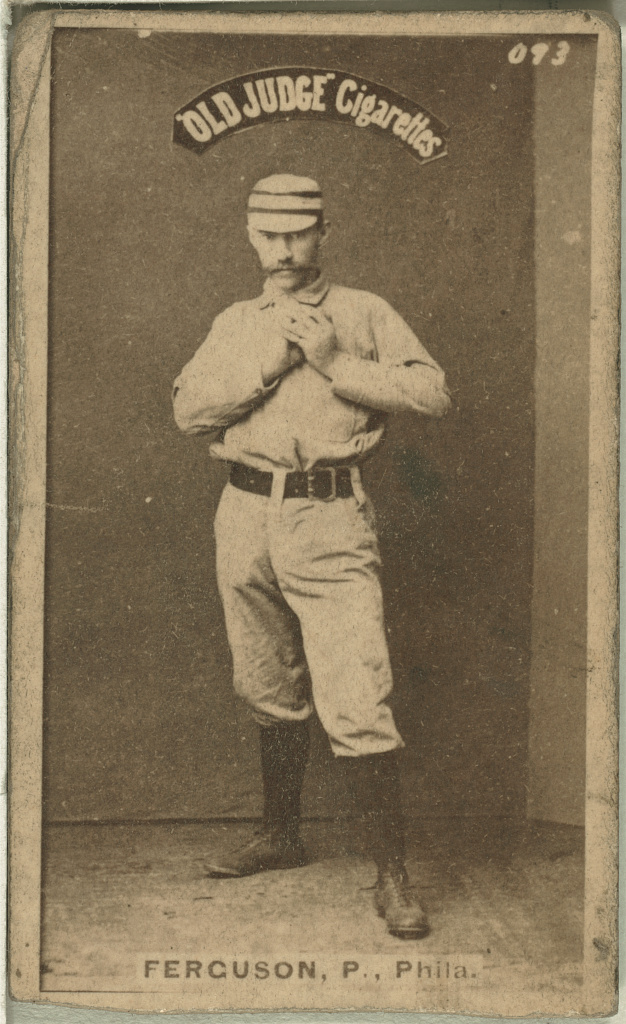

Charlie Ferguson

One of the first tragic figures in major-league baseball, Charles Ferguson might have become one of the greatest players of all time had it not been for his untimely death at the age of 25. An all-around natural athlete who starred for the Philadelphia Quakers of the National League from 1884 through 1887, Ferguson had a short yet brilliant career and is perhaps the greatest forgotten star of the 19th century.

One of the first tragic figures in major-league baseball, Charles Ferguson might have become one of the greatest players of all time had it not been for his untimely death at the age of 25. An all-around natural athlete who starred for the Philadelphia Quakers of the National League from 1884 through 1887, Ferguson had a short yet brilliant career and is perhaps the greatest forgotten star of the 19th century.

Charles Ferguson’s story begins in rural Charlottesville, Virginia, at the height of the Civil War. He was born in the shadows of the University of Virginia on April 17, 1863, to G.M. and Teresa Ferguson at No. 275 West Main Street in what was then the Random Row or Vinegar Hill1 area of Charlottesville.2 G.M. Ferguson was a neighborhood baker who built small wooden additions on either side of the family home and rented them to other Random Row merchants who operated “grocery” stores. Compared with most Random Row residents of the 1860s and 1870s, Charles Ferguson was born into relatively stable circumstances.

There is relatively little known about Ferguson’s childhood. However, Random Row in the mid-19th century provides a glimpse into the environment in which he grew up. Many of the early residents of the neighborhood were Irish immigrants, several hundred of whom moved into town with railroad construction crews around 1850.3 There were several bars along Main Street and the area had a reputation as a center for moonshining. Alcohol-induced brawls were common occurrences. Nearly half a century earlier Thomas Jefferson had specifically selected the site for the University of Virginia atop a small hill a mile from the center of Charlottesville in large part because of his “suspicions about the city.”4 The area was also home to a 500-bed military hospital that treated thousands wounded in the Civil War.

The war ended two years after Ferguson’s birth. By then thanks in large part to Union soldiers playing baseball in Confederate territory, the popularity of baseball began to spread to the South. Charlottesville, given its proximity to the North, was no exception. The game became such a popular pastime at the University of Virginia that Ferguson and other young residents of Charlottesville certainly would have been introduced to it at a young age.

Numerous sources claim that Ferguson was discovered while playing college baseball. The Sporting News and the Washington Post wrote that he attended the University of Virginia. The Philadelphia Inquirer and numerous Internet sources identify him as a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania. All those accounts are incorrect. The registrar’s offices at both institutions have no record of Ferguson having attended. But although Ferguson was not a student, he did suit up for the University of Virginia’s nine in 1882. Athletic teams were loosely affiliated with institutions of higher education in the 1880s and it was common practice to have nonstudents don the institution’s colors. And during the 1882 season Ferguson attracted the attention of Henry Boachen, a leather merchant who owned an independent team in Richmond.5 Boachen signed Ferguson and brought the young right-hander to Richmond, where he both pitched and caught during the 1883 season.

Meanwhile, in Philadelphia the National League’s new Philadelphia Quakers (Phillies), who had joined the league after the Worcester Ruby Legs dropped out, were locked in a battle for the hearts of the city’s baseball fans with the Philadelphia Athletics of the American Association. The Quakers finished their inaugural season in 1883 with a dismal 17-81 record, while their swashbuckling crosstown rivals had just captured the Association pennant in a thrilling race with the St. Louis Browns that went down to the season’s final days. Al Reach, owner of the Quakers, knew he needed something to turn the team around.

That something came in the form of Charles Ferguson. He signed with the Quakers in the spring of 1884 for a salary of $1,500 and made his major-league debut against the Detroit Wolverines on May 1 at Recreation Park in Philadelphia. What a debut it was! Providing a preview of his all-around abilities, Ferguson pitched a complete game, tripled and singled twice to lead the Phillies in a 13-2 thrashing of the Detroit Wolverines. The young right-hander finished the season at 21-25 with a 3.54 ERA as he hurled 417 innings for a team that posted a 39-73-1 record.

In 1885 Ferguson solidified himself as one of the best pitchers in the National League and one of the team’s best hitters in leading the Quakers to their first winning season. On the mound he improved upon his 1884 showing with a 26-20 mark and 2.22 ERA and on August 29 he tossed the franchise’s first no-hitter, a 1-0 blanking of the Providence Grays. However, it was his speed and work with the bat that caused manager Harry Wright to take notice and insert him into the lineup as an outfielder when he wasn’t pitching. Ferguson appeared in 15 games in the outfield and finished the season with a more than respectable .306 batting average in 235 at-bats. (To place this into context, his .306 average was 77 points higher than the Quakers’ team average and 65 points above the National League average.)

The 1886 season was Ferguson’s finest as a pitcher. He notched 30 victories against only nine defeats and recorded an ERA of 1.98. A case could be made that he was the league’s best pitcher that season. He ranked second in winning percentage (.769), second in ERA, sixth in wins, first in saves (2), and second in WHIP (walks and hits per inning pitched, at 0.976). Statistics aside, his brilliance on the mound was never more evident than in the way he finished the season. Ferguson won his last 11 starts and played spoiler on the season’s final day when he pitched two complete-game victories over the Detroit Wolverines6, ending any pennant hopes the Detroiters may have had.

Despite all the success he enjoyed on the mound, the season was not free of controversy for Ferguson. On August 27, upon the Quakers’ arrival in Chicago for a three-game set, the young right-hander jumped the team and headed back to Charlottesville. The situation suggests that all may not have been well with the Quakers’ star. Ferguson began explaining his actions by stating, “It is true that I jumped the Philadelphia club at Chicago, but I did not take ‘French leave’ because I feared the Chicago batsmen.”7 The lineup of the first-place Chicago club was indeed one to be feared as they tallied 13 runs in each of the three contests against the Quakers. Ferguson continued explaining, giving the following account:

“I left because I feared a long spell of sickness. I was sick when we left Philadelphia on our last trip, and when we reached Chicago I felt so bad it was impossible for me to play. I told Mr. Wright I could not stand it any longer and that while I was able to travel, I desired very much to go home to Charlottesville, Virginia where I was sure to receive the attention I knew I required. I begged Mr. Wright to allow me to go home, but he refused to let me do so. After begging and pleading for some time I made up my mind that I would take the first train out of Chicago for the South. … Since my connection with the Philadelphia team I have worked hard and faithfully, and have given my manager very little trouble by always striving to please him. I am satisfied my friends in Philadelphia are at a loss to know what my excuse for my action at Chicago, and I take this method of giving them the exact facts. Mr. Wright may have – I will say he did have – doubts about the seriousness of my case, or he would surely have let me go home. When I arrived home I was confined to my bed for ten days, and here is a physician’s certificate to that effect.”8

Whether it was illness, fatigue, or the need to simply get away for a few days, Ferguson rejoined the team in Philadelphia after its long road trip.

With each successive season Ferguson’s value to the Quakers become more evident and he appeared more frequently in the field on days when he wasn’t pitching. In 1886 he played in 27 games in the outfield and the following year he appeared in 38 games as a position player, the first time he appeared in the field more often than on the mound. It was evident that at this point in his career he was on the path to transitioning to an everyday player.

Ferguson’s 1887 season may represent his best for all-around performance. On the mound he recorded a 22-10 mark, good enough for the second highest winning percentage in the National League, with a 3.00 ERA that ranked third best in the league. At the plate, his offensive production reached a point that moved Wright to increasingly find a spot in the lineup for him. By that season’s end, Ferguson had become the Quakers’ everyday second baseman when he wasn’t pitching.

The final days of the 1887 season witnessed the greatest hot streak of Ferguson’s career. In the Quakers’ final 17 games the club won 16 and tied one to move into second place. Ferguson appeared in all 17 games, hitting .361, compiling a 7-0 pitching record with a 1.75 ERA, and recording an unheard-of .963 fielding percentage at second base,9 an incredible feat when compared to the entire NL’s .908 fielding percentage for the season. For the year Ferguson finished with a .337 average and a team-leading 85 RBIs as the Quakers finished the season in second place only 3½ games behind the Wolverines, the club’s best finish during Ferguson’s brief career.

After the 1887 season other clubs expressed interest in acquiring Ferguson’s services and it was reported that at least one club bid $10,000 for him. However, coming off the great finish of 1887 and considering the economic impact of the large crowds his star player was drawing, Reach thought twice about selling Ferguson and opted to keep him.

Sometime during the Quakers’ spring preparation for the 1888 season, Ferguson probably consumed contaminated food or water. Within days, the tiny red spots that signaled typhoid fever appeared on his chest. With his health quickly deteriorating, the Quakers’ star hurler was sequestered in the second-floor bedroom he and his wife rented from Quakers shortstop Arthur Irwin. Ferguson battled the ailment for nearly a month, periodically rallying, before succumbing on April 29, 1888, at 10:30 p.m., less than two weeks after his 25th birthday. Ferguson’s remains were returned to Charlottesville the next day and he was interred at Maplewood Cemetery after a funeral attended by the entire Quakers organization and players on the Princeton College team, which Ferguson had coached in the offseasons.. (Princeton College is now Princeton University.)

Ferguson’s death sent shockwaves through the entire baseball community. To that point in baseball history, he may have been the most prominent active major leaguer to die during his playing career. To honor Ferguson, the Quakers along with the Washington Nationals, New York Giants, and Boston Beaneaters wore black crepe on their left sleeves during the season.10

Ferguson had married sometime between the 1885 and 1886 seasons. He and his wife had an infant daughter, who died in June of 1887. She, too, is interred at Maplewood Cemetery. The couple had no other children.

Ferguson spent his offseasons coaching. There are numerous mentions of him coaching Princeton’s club baseball team. However, university athletic archives do not mention him as being affiliated with the team, presumably because this was before baseball was an officially recognized university team.

Over his brief four-year career Ferguson compiled a 99-64 record with a 2.67 ERA. At the plate he finished with a .288 career mark with 157 RBIs. While Ferguson’s career statistics did not reach levels usually attributed to greatness, many years after his death his exploits on the baseball field were still vividly remembered by those who saw him play. In 1924 sportswriter W.B. Hanna included Ferguson on his 25-man roster of greatest players in baseball history. Interestingly, Hanna tabbed Ferguson for this honor on the basis of his ability on the mound, in the field, and at the bat. “Ferguson belongs in the ‘twenty-five’ because he was the game’s best all around player,” Hanna wrote. “There have been men who could look after as many positions, but none who could play them all so well. Ferguson was a pitcher, good enough to be a regular on any ball club of the present; he was a good second baseman, not just a filler-in, but good; he could play the outfield well enough to make the absence of the regulation no handicap, and he was a first class batter. There hasn’t been an all around man since his day to equal him.”11

In 1925 Leo Riordan, sports editor of the Philadelphia Evening Public Ledger, called Ferguson the greatest ballplayer who ever lived. “That goes, too, despite Ty Cobb. I’ll tell you why. Ferguson could play every position on the team. One year he started to pitch for us [the Quakers] and wound up on second playing as well as Eddie Collins. … No better base runner ever lived.”12

Perhaps the greatest testament to Ferguson’s abilities as a ballplayer came from one of his contemporaries, Wilbert Robinson. Robinson was a catcher for the crosstown rival Philadelphia Athletics before going on to a Hall of Fame career as a player and manager with the Baltimore Orioles and Brooklyn Robins. When asked in 1931 to name the five greatest ballplayers of all time, Robinson rated Ferguson as the fifth greatest, saying: “Back in the old, old days the Phillies had a man who could pitch like a streak and play the infield, too. His name was Charley Ferguson. You can’t leave him off. … But if I have to name the best five you can put down Cobb, Keeler, Ruth, Wagner, and Ferguson for me.”13

One can only imagine how many games Ferguson might have won or what kind of everyday player he would have developed into had he lived to play an additional 12 to 15 years. However, based on the accolades he received from those who saw him play, Charles Ferguson may very well have been enshrined in Cooperstown next to the greatest players the game has seen.

Sources

1886 Philadelphia Phillies Team Schedule. Retrieved on June 19, 2011, from http://www.baseball-almanac.com/teamstats/schedule.php?y=1886&t=PHI

J. Alexander, Early Charlottesville Recollections of James Alexander, 1828-1874. (Ed. Mary Rawlings). Charlottesville, Virginia: The Michie Co., Printers, 1942

“Charles Ferguson.” Retrieved on June 19, 2011, from http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/f/ferguch01.shtml

Charlottesville: A Brief Urban History. (2005). Retrieved from http://www2.iath.virginia.edu/schwartz/cville/cville.history.html

Frank Fitzpatrick, “Charlie Ferguson Seemed Headed for a Place in Baseball Lore: The Short Life and Tragic Death of a Long-ago Phillies Phenom.” Philadelphia Inquirer, February 23, 2003, D01.

“Dressed To The Nines: Misc. Uniform Markings.” Retrieved on June 5, 2010, from

http://exhibits.baseballhalloffame.org/dressed_to_the_nines/patches.htm.

“Ever Hear of Charles Ferguson?” Retrieved on August 13, 2010, from http://www.baseball-fever.com/showthread.php?38520-Ever-Hear-of-Charlie-Ferguson&p=1001135

“Ferguson’s Funny Break: He Tells Just Why He Jumped the Philadelphia’s at Chicago.” The Sporting News, September 27, 1886.

W.B. Hanna, “The Twenty-five Greatest Players,” Baseball Magazine, 33 (1), 1924: 229-230.

“History of Vinegar Hill” (2005). Retrieved on June 17, 2010, from http://www2.iath.virginia.edu/schwartz/vhill/vhill.history.html

G. Penn, “Baseball’s Ferguson Hailed From City’s Random Row.” Charlottesville Daily Progress, 1958.

“Philadelphia Phillies Team History & Encyclopedia.” Retrieved on June 21, 2010, from http://www.baseball-reference.com/teams/PHI/

Frank V. Phelps and James Sumner, “Charles J. Ferguson” in Nineteenth Century Stars. Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 1989.

“Pitcher Ferguson’s Burial,” New York Times, May 1, 1888, p. 1.

“Pitcher Ferguson Dead: The Noted Twirler of the Philadelphia Club and a Famous Player Passes Away.” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 30, 1888.

Notes

1 The name Random Row stems from the way the houses were built without reference to the old town lines, while the name Vinegar Hill was a reference to the illicit alcohol trade carried on by people doing business as grocers who labeled their casks containing spirits as “vinegar.” See Penn, G. “Baseball’s Ferguson Hailed From City’s Random Row.” Charlottesville Daily Progress, 1958.

2 J. Alexander, Early Charlottesville Recollections of James Alexander, 1828-1874. (Ed. Mary Rawlings). Charlottesville, Virginia: The Michie Co., Printers, 1942, 98.

5 Baseball Hall of Fame documents used in Frank Fitzpatrick, “Charlie Ferguson Seemed Headed for a Place in Baseball Lore: The Short Life and Tragic Death of a Long-ago Phillies Phenom.” Philadelphia Inquirer, February 23, 2003, D01.

8 Ibid.

9 Frank V. Phelps and James Sumner, “Charles J. Ferguson” in Nineteenth Century Stars. Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 1989.

13 “Ever Hear of Charles Ferguson?” Retrieved on August 13, 2010, from http://www.baseball-fever.com/showthread.php?38520-Ever-Hear-of-Charlie-Ferguson&p=1001135.

Full Name

Charles J. Ferguson

Born

April 17, 1863 at Charlottesville, VA (USA)

Died

April 29, 1888 at Philadelphia, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.