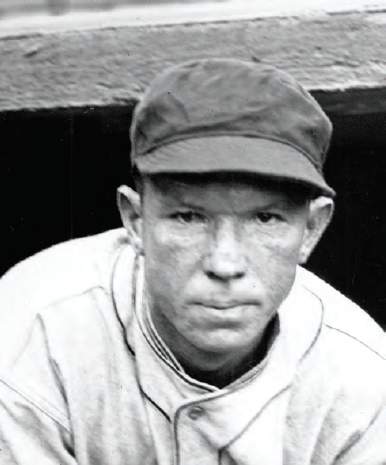

Red Worthington

California native Red Worthington was a hard-hitting outfielder with a powerful throwing arm. A top prospect in the St. Louis Cardinals organization, Red, who threw and batted right-handed, appeared to be on the fast track to major-league stardom. Before his ascent to the major leagues, a sportswriter wrote of Worthington, “This young man from the Pacific Coast does many things well but his hitting and throwing are the accomplishments that gave observers their biggest thrill during training games in Florida. Too, he owns that indefinable quality called COLOR or personality. He makes friends with the kids and the grown ups. He’s the sort that can breeze into town in the morning and know everybody in the afternoon. Red, if he doesn’t break an ankle, will be in the majors next year or the year after that anyhow.”1

Brought up through the Cardinals farm system, Worthington was unable to break into the Cardinals’ talented outfield ranks, and was sold to the Boston Braves. Four years later, he returned to the Cardinals in a waiver deal, and in his only at-bat with the 1934 pennant winners, he struck out.

Robert Lee “Red” Worthington was born on April 24, 1906, in San Gabriel, California. He was the second youngest of seven children born to Jerry Worthington, a laborer, and Hannah (McNamara) Worthington. Hannah and Jerry were Irish Catholics from Illinois. The Worthingtons were married in 1891 and left Illinois around the turn of the 20th century. They lived briefly in Iowa and Kansas before moving California. The family first lived in San Gabriel before settling in nearby Alhambra.

Red, who derived his nickname from the color of his hair, played baseball on the local lots of Alhambra. According to San Gabriel Valley Tribune sportswriter Jim McConnell, Worthington briefly attended Alhambra High School in the early 1920s but did not graduate.2 The Los Angeles area was noted for its year-round amateur and semipro baseball leagues during the early and mid-20th century. There is little information available on Worthington’s amateur days on the diamond, but by the summer of 1925 the 19-year-old outfielder was traveling the country with a semipro team from Los Angeles. While playing at Eldora, Iowa, he caught the attention of a scout for the Waterloo Hawks of the Class D Mississippi Valley League, who signed him on the spot. Joining the Hawks in the middle of July, he hit .273 in 57 games. In 1926 he had a breakout year, leading the league with a .389 batting average. His 185 hits that season were the most in Mississippi Valley League history.3

The St. Louis Cardinals purchased Worthington’s contract from Waterloo at the end of the 1926 season. Cardinals general manager Branch Rickey wanted to see how the youngster would fare in the high minors so he sent Worthington to the Syracuse Stars in the Double-A International League. Never short on confidence, Worthington wrote in a letter to the Stars’ president of baseball operations, Warren Giles, “I hope Mr. Shotton (Syracuse manager Burt Shotton) isn’t one of those strawberry pickers that picks out his lineup in the middle of the winter because if he is I’m afraid I’ll have to spoil some of his plans. I am going to break into that Syracuse outfield. I have looked up the records of the others on the payroll and I am convinced that I will be banging the ball all over the lot for you. I’ll be one of the first men to training camp and I am confident when I leave Syracuse it will be to go up to the majors and not to slip down.”4

True to his word, Worthington earned a spot on the Syracuse roster. Shotton used him as a reserve outfielder and pinch-hitter. Worthington had a respectable year moving up from Class D to the highest level of the minors, hitting .261 in 73 games. In the outfield, he recorded eight assists while committing only three errors.

In January 1928, the Syracuse franchise was sold and the players were transferred to Rochester.5 In early March, Branch Rickey traded Worthington to Danville of the Class B Three-I League for outfielder Frank Murphy. Commenting on the deal, The Sporting News wrote, “Worthington was with Syracuse last season and several games were pulled out of the fire by his timely blows which came when hits meant runs and the ball game.”6

Scarcely had Worthington settled in with Danville than Houston Buffaloes outfielder Homer Peel, a highly touted St. Louis prospect, ran into an outfield fence and broke his leg. Rickey sent Worthington to the Texas League club to help fill the void. While Worthington, a dead pull hitter, was in Houston, manager Frank Snyder taught him the art of hitting the ball to all fields.

The Texas League played a split schedule in 1928 and Worthington’s hot bat helped the Buffaloes win the first half of the season. He finished the season with a .353 batting average, 47 doubles, 11 triples, 7 home runs, and 12 stolen bases. His 211 hits topped the circuit and he struck out just 16 times in 599 at-bats. In the outfield, his strong arm accounted for 19 assists. Houston defeated Wichita Falls, the second-half winner, in the league playoff, then defeated the Southern Association champion Birmingham Barons in the Dixie Championship. Worthington and four other Houston players were selected to the Texas League all-star team.

A few weeks before the start of spring training in 1929, Worthington informed Rochester president Warren Giles that he would not report to the team until he received a higher salary. Meanwhile, Hillerich & Bradsby, maker of the Louisville Slugger, informed Giles that Worthington’s bats would be shipped to the team in time for the start of spring training. Giles wrote back to Worhington, “What kind of holdout are you, anyway? You tell me you are not going to report but you tell the bat company to get your bats to camp before opening day practice. “It only costs three cents to try,” Worthington replied, enclosing his signed contract with the letter.7

Red put together a big year for the Red Wings in 1929. The 5-foot-10, 170-pound outfielder, who swung a 42-ounce bat, batted .327, with 202 hits, 34 doubles, 15 triples, 8 home runs, and 113 RBIs. He had 21 outfield assists. Rochester won 103 games and captured the International League crown for the second year in a row, but lost to the Kansas City Blues of the American Association in a hard fought Junior World Series, five games to four.

The Cardinals’ roster was loaded with talented outfielders, so Worthington was back with Rochester for the start of the 1930 season. On April 13 the Red Wings played an exhibition game against the Washington Senators. Washington pitcher Carlos Moore took a swing and the bat flew across the diamond and struck Worthington on the elbow of his throwing arm. The Cardinals’ team physician, Dr. Robert F. Hyland, reported that there was a torn ligament but no fractured bones. The severity of the tear forced Worthington to miss six weeks of the season. The injury was so bad that he considered learning how to throw left-handed.

During this time, the Red Wings were hit with a number of injuries and they began to drop in the standings. The loss of Worthington along with player-manager and star center fielder Billy Southworth had the most impact on the team.8

In late May, cleared by Dr. Hyland to play, Worthington rejoined the Red Wings and resumed his hot hitting. On June 20 he reinjured his elbow crashing into the outfield wall in the first game of a doubleheader against Reading. But he returned to the lineup in the nightcap, banging out two hits and throwing a runner out at the plate.

Worthington went on to have a fine season, hitting .375 with 25 doubles and 12 triples in 123 games. His arm gave him trouble for most of the season but he still finished with 11 outfield assists. Winning 105 games, Rochester again took the International League pennant, and defeated the Louisville Colonels in the Junior World Series.

Rickey, having an abundance of talent in his farm system, sold Worthington and utilityman Charlie Wilson to the Boston Braves on September 17, 1930, for a reported $60,000. In his first spring training with the Braves, Worthington got off to an amazing start. By April 7, he had compiled 47 hits in 67 spring-training at-bats against major-league pitching for a .701 batting average. Babe Ruth and Wilbert Robinson spoke glowingly about his prowess with the bat. Ruth told a reporter for The Sporting News that Red was a natural hitter who would do well in the big leagues. Robinson in an interview with the Associated Press said that in his opinion, Worthington was the best batter on the Braves roster. The Associated Press also reported that Branch Rickey was following Worthington’s hitting exploits and considering a deal with the Braves to reacquire the slugging outfielder.

Red’s good showing in spring training earned him a spot in the Braves’ starting outfield, replacing Lance Richbourg, who was moved to the infield. On April 20 Worthington was hit in the mouth by a foul ball that caromed off the netting behind home plate. The injury forced him to sit out the next three games. When he returned, Red did not miss a beat, lashing a triple in his first game back in the lineup. He continued to hit well so the Braves moved him to the cleanup spot in the batting order. The Sporting News observed, “Bob is one of the best of the Brave hitters and does very well in the pinches. He bats right-handed but does not seem to care if a right-hander is pitching.”9

By the end of June, Worthington had been shifted from right field to left and was clubbing the ball at a .333 clip. He and fellow outfielders Wes Schulmerich (another rookie) and second-year man Wally Berger were the backbone of the Braves’ offensive attack. A late-season swoon brought Worthington’s average down to .297 but it was a solid year for the rookie. He was not a basestealing threat but he ran well enough to leg out 25 doubles and 10 triples. Defensively, he was sure-handed in the field and covered a lot of ground. In 1931 he led National League outfielders with a .988 fielding percentage and finished second with 8 outfield assists.

Worthington shook off any type of sophomore jinx and after 17 games in 1932 he was hitting .360 with four home runs. He cooled off a bit as the campaign wore on but he was still batting over .300 when a broken ankle, suffered sliding into third base in a game against Pittsburgh, ended his season on August 7. The Braves were in third place when Worthington was injured. He was hitting .303 with 35 doubles, 8 triples, 8 home runs and 61 RBIs. Without him the club faltered, ending up in fifth place.

When spring training began in early March 1933 at St. Petersburg, Florida, neither Worthington nor shortstop Billy Urbanski, was in camp on time. Braves manager Bill McKechnie was not happy, telling an Associated Press reporter, “If Urbanski and Worthington know what side their bread is buttered on, they won’t do much quibbling this season.”10

As it turned out, Red had gotten married in the offseason to his high-school sweetheart, Bernice Brown, and he was a few days late reporting to camp. His ankle had healed sufficiently over the winter and he appeared to be back in form. But when the season started he began suffering from debilitating dizzy spells, possibly vertigo, and was sent home after playing in only 17 games. In late June, Worthington had his tonsils and adenoids removed. Recuperating from these maladies, he missed the rest of the season. Once the 1934 season started, he was mainly used as a pinch-hitter and by late June his batting average was round .300. His bat cooled off during the next few months and Boston put him on waivers on September 11. The Cardinals, who were attempting to gain ground on the first-place New York Giants and trying to hold off the hard-charging Chicago Cubs, claimed Worthington.

On September 14 the Cardinals lost to the Giants 4-1 at the Polo Grounds. Worthington was sent up to pinch-hit for pitcher Bill Walker in the sixth inning and the Giants’ Hal Shumacher struck him out. St. Louis went 13-2 down the stretch, edging out the Giants by two games for the pennant. Cardinals manager Frankie Frisch did not play Red in any other regular-season games or in the World Series. Sportswriter Jim McConnell suggested that the main reason Rickey signed Worthington was to keep the Cubs or Giants from picking him up during the tight pennant race.

Still under contract with the Cardinals in 1935, Worthington reported to spring training in Bradenton, Florida. Frisch informed the players that he would carry only five outfielders on his roster. Veterans Jack Rothrock and Ducky Medwick were guaranteed to make the team. That left Ernie Orsatti, Gene Moore, Johnny Winslett, Terry Moore, and Worthington to fight it out for the remaining three outfield spots.

Red pinch-hit and played the outfield in spring training and from all accounts, it appeared that he had a good chance of making the team. That all changed in early April when Worthington, Dizzy Dean, and Charlie Gelbert missed the team train at Dublin, Georgia. The three hastily rented a car and sped off to the team’s next stop, Macon. When they arrived the next morning, Frisch was furious. He fined Dean $100 and Gelbert $50 and sent Worthington and Charlie Wilson, who had started trouble on the train, back to St Louis.

A few days later, the New York Yankees worked out a deal to acquire Worthington while allowing the Cardinals to retain the rights to his contract. The Yankees optioned Red to their Pacific Coast League team in Oakland. In July he was sent to the Mission Reds, who played in San Francisco. For the season, he slumped to .247.

In the offseason Rickey transferred Worthington to Houston. On March 26, 1936, he was traded from Houston to Sacramento of the Pacific Coast League for catcher Harold Doerr. Worthington seemed to rediscover his batting stroke with the Solons, hitting .306 in 127 games. Defensively, he played well, committing only three errors in the outfield. He also filled in as the manager when Bill Killefer was called home late in the season.

Worthington stayed on with Sacramento as a player and coach in 1937 but injures limited him to 30 games in the outfield. Including pinch-hitting appearances, he finished what would be his last season in Organized Baseball with a respectable .304 batting average.

Worthington was released by the Solons in March 1938. He went on to work at a variety of jobs after baseball, including gardener and machinist, before serving as an Army warrant officer during World War II. After the war, he was employed at the Lucky Lager Brewing Company in Azusa, California.

In the fall of 1963 Worthington underwent surgery for a duodenal ulcer. Complications arose and he contracted pneumonia. He never recovered and died at the age of 57 on December 8, 1963, at Sawtelle Veterans Hospital in Los Angeles. His obituary in the Los Angeles Times noted that he was survived by a sister and two brothers.11 Worthington’s funeral Mass was held at All Souls Church in Alhambra and he was buried in San Gabriel Mission Cemetery.

Sources

Berkeley (California) Daily Gazette

Helena (Montana) Independent

Lawrence (Kansas) Journal World

Los Angeles Times

Pittsburgh Press

Rochester (New York) Evening Journal and The Post Express

The Sporting News

Sunday Morning Star (Wilmington, Delaware)

Syracuse Herald

Telegraph and Times Journal (Dubuque, Iowa)

Wikipedia.com

Baseball-reference.com

Retrosheet

San Gabriel Valley Tribune sports writer Jim McConnell, telephone interview, June 26, 2013.

Special Thanks:

Alhambra High School librarian Cathy Doran

Alhambra Historical Society

Sister Kathleen Callaway, Ramona convent secondary school

Bill Thomas, Loyola High School alumni relations director

San Gabriel Valley Tribune sports writer Jim McConnell

Notes

1 Cray L. Remington, “Red Worthington Is Young But He Knows Plenty About the Gentle Art of Filling an Outfield Position,” Rochester (New York) Evening Journal and The Post Express, April 8, 1929, 17.

2 The 1940 US Census lists Worthington as a high-school graduate, but his draft registration card in 1942 lists his education as one year of high school. An article by San Gabriel Valley Tribune sportswriter Jim McConnell, published on July 6, 2010, called Worthington an alumnus of Alhambra High School. School librarian Cathy Doran went through every yearbook from 1921 through 1926 and found no record of Worthington ever attending the school. She checked the yearbooks’ baseball team pictures and he was not present in any of them. McConnell told the author in a telephone interview that his research along with an interview with Max West (a former major leaguer and Alhambra resident) points to Worthington briefly attending Alhambra High School. Sister Kathleen Callaway, a Catholic historian, assisted me in tracking down possible Catholic schools in the Alhambra area that Worthington might have attended. Loyola High School in Los Angeles seemed a viable choice, but alumni relations director Bill Thomas reported that Worthington is not listed in the school’s records. Further research throughout the Los Angeles school system yielded no information on Worthington’s educational background.

3 The Mississippi Valley League was a Class D league that operated from 1922 through 1932. In 1933 the circuit upgraded to Class B status in its final year of existence.

4 Syracuse Herald, January 23, 1927, 47.

5 Syracuse’s refusal to build a new ballpark led the Cardinals to sever ties with the city. St. Louis sold the Syracuse franchise to Frank Donnelly and a group of investors from Jersey City. The Cardinals then purchased the International League team in Rochester for a reported $130,000. The Syracuse players were transferred to Rochester and the Rochester team’s roster from the previous year was sent to Jersey City. Rochester changed its name from the Tribe to the Red Wings in honor of its new ownership.

6 The Sporting News, March 8, 1928, 2.

7 Helena (Montana) Independent, March 17, 1929, 8.

8 Southworth missed a number of games with a broken finger. In addition, he was called home during the season after his wife lost twins during childbirth.

9 The Sporting News, May 7, 1931.

10 “McKechnie Warns Red Worthington to Watch His Step,” Rochester Evening Journal and The Post Express, March 7, 1933, 12.

11 Worthington’s wife, Bernice, was not mentioned in the Los Angeles Times death notice or obituary, nor were any children mentioned. I contacted the San Gabriel Mission Cemetery, the San Gabriel Cemetery and a number of other Los Angeles cemeteries in search of Bernice Worthington’s grave but I was unable to find any information regarding her interment. The last mention of Bernice Worthington was in the 1942 Alhambra City directory.

Full Name

Robert Lee Worthington

Born

April 24, 1906 at Alhambra, CA (USA)

Died

December 8, 1963 at Sepulveda, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.