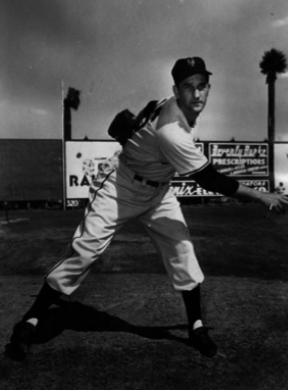

Larry Jansen

It is largely forgotten that Larry Jansen was the winning pitcher when Bobby Thomson hit his “Shot Heard Round the World” to dramatically win the 1951 pennant in the Polo Grounds. Indeed, without Jansen, it is highly unlikely that the Giants would have even been in the playoff against the Brooklyn Dodgers. With 23 victories to tie Sal Maglie for the most wins in either league, he was by any measure one of the top pitchers in baseball in 1951.

It is largely forgotten that Larry Jansen was the winning pitcher when Bobby Thomson hit his “Shot Heard Round the World” to dramatically win the 1951 pennant in the Polo Grounds. Indeed, without Jansen, it is highly unlikely that the Giants would have even been in the playoff against the Brooklyn Dodgers. With 23 victories to tie Sal Maglie for the most wins in either league, he was by any measure one of the top pitchers in baseball in 1951.

Perhaps more importantly, Jansen was a key figure in the Giants’ famous drive to the pennant. He started the Giants on the way back after they fell 12½ games off the pace on August 12, beating the Phillies 5-2 the next day. Overall Jansen won eight of 10 decisions during their memorable 37-7 stretch drive. Teammate Monte Irvin labeled Jansen the Giants’ “Meal Ticket.”1

After losing to the Cardinals in St. Louis 4 -3 on September 11, Jansen, during the last two weeks of the season, won his next four starts, pitching complete games in each and allowing only four earned runs in 36 innings. He defeated the Philadelphia Phillies 10-1 on September 26 to keep the surging Giants within one game of the lead. Then on September 30, the last day of the regular season, he won his 22nd victory, beating the Boston Braves 3-2 in Boston to put the Giants temporarily in the lead for the pennant.2 His 23rd victory was the famous Bobby Thomson home run game; Jansen had entered the game in relief of Sal Maglie in the top of the ninth inning with the Giants down 4-1. He retired the Dodgers in order to set the stage for the bottom-of-the-ninth heroics.

At the time Jansen was 31 years old. He did not win his first major-league game until he was 26, but now, in only his fifth big-league season, he already had 96 wins to his credit, winning 21, 18, 15, 19, and 23 games in consecutive seasons. Plagued by back and then arm trouble after 1951, Jansen recorded only 26 more major-league victories, appearing in his last big-league game with the Cincinnati Reds in 1956. That chronic back ailment derailed a career that had Hall of Fame potential. One noted historian went so far as to label Jansen “the most overlooked pitcher” of his era.3

Larry Jansen was born on July 16, 1920, as one of eight children on a 90-acre farm near the small Dutch community of Verboort, in northwestern Oregon. His high school had only nine boys, so at one point Jansen, who was over 6 feet tall, and his brothers made up the entire basketball team. But early on, baseball attracted Jansen’s attention, spurred on by his baseball-loving father, Albert. At the age of 9, Jansen earned his first baseball glove by picking strawberries for 3 cents a box.4

As he got older, Jansen played shortstop on the town team, but showed an immediate knack for pitching when he was asked to finish a one-sided game in relief.5 He dominated the opposition in the semipro league, prompting his manager, Herb Kappel, to arrange a tryout with the San Francisco Seals of the Pacific Coast League the next time the Seals played in nearby Portland. There Jansen pitched batting practice to Seals manager Lefty O’Doul, one of the great hitters in baseball history, with mixed results. O’Doul saw enough, however, to invite Jansen to the Seals’ training camp the next spring.6

During training camp O’Doul offered Jansen a contract for $90 a month to pitch for the Tucson Cowboys in the Class D Arizona-Texas League for the 1939 season. Jansen balked at the low salary and decided to return to the family farm and again pitch for the local semipro team. Back at home, his pitching again drew notice and Ernie Johnson, a Boston Red Sox scout, signed Jansen for a $500 bonus to a blank contract for 1940.

Jansen married his hometown sweetheart, Eileen Vandehey, that winter on January 18 in Verboort. The couple would raise 10 children, five girls and five boys, and be married for almost 70 years. Their son Dale pitched in the Giants organization for a couple of years in the 1960s. Jansen always maintained a sense of humor about his large family, often saying that when he went on picnics he would let “everybody else collect his kids and [then he would] take what’s left.”7

After signing, Jansen heard nothing more from the Red Sox all winter. Finally when March rolled around with still no word from the Red Sox, a semipro umpire advised Jansen to wire baseball commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis. He did so and got a prompt reply stating, “Am investigating but at any rate you are a free agent.”8

Jansen then wired O’Doul of the Seals that he was again available, and after another tryout, agreed to sign. The Seals sent the 19-year-old to Salt Lake City in the Class C Pioneer League for the 1940 season. Jansen broke in with a bang, leading the Bees to the pennant by 12½ games by winning 20 games against seven losses. His .741 winning percentage and 2.19 earned-run average both led the league and he was named to the league all-star team.

That performance earned Jansen a spot with the Seals for 1941 and he again did not disappoint, going 16-10 with a 2.80 ERA for the fifth-place Seals. Still Jansen, a lanky 6-feet-2 and 165 pounds, had his doubters. His fastball was not much to write home about and his curve wasn’t outstanding either. In fact, he struck out only 70 batters in 238 innings in 1941. But he had a calm, businesslike demeanor on the mound and excellent control and got hitters out, even though they would walk back to the dugout wondering why they couldn’t hit the guy.9

Doubts about whether Jansen could be successful at the next level were not helped when he struggled with the Seals in 1942. During the year Larry Woodall, one of the coaches, taught Jansen how to throw a slider. Although he didn’t have much immediate success with it, finishing the year with an 11-14 record, a 4.32 earned-run average, and 222 hits allowed in 173 innings, the development of a slider would prove to be the turning point in his career.10 Jansen’s mediocre year, however, was largely due to physical problems. He was felled by pneumonia in May and lost 15 pounds, was hit in the cheekbone with a batted ball and later battled a sore heel.11

Jansen was set to report to spring training with the Seals for 1943 when his draft board told him that he was about to be inducted. Jansen now had a family and considered his options. The draft board told him that if he elected to stay and work on the farm, he would not be inducted right away because he would be working to support the war effort. As a result, Jansen did not report to spring training and found himself on baseball’s suspended list for 1943.12

Jansen stayed on the farm for two years, milking 27 cows a day and raising a truck garden. He was placed on baseball’s voluntarily retired list for 1944. He did manage to play baseball twice a week, pitching for McElroy’s Ballroom in Portland, the state semipro champs, as well as a team in Eugene.13 He also used the time to master his slider, beefed up from about 165 to 188 pounds, and when he returned to the Seals for the last six weeks of the 1945 season after the war ended, he was a much improved pitcher.14

During the last of the ’45 season, Jansen went 4-1 with five complete games in seven starts. Then in 1946 it all came together for both Jansen and the Seals. Together with future major-league All-Star Ferris Fain, Jansen led the Seals to the Pacific Coast League pennant and the Governor’s Cup, with one of the finest minor-league performances in history.15 Jansen won 30 games, plus two more in the playoffs, and led the league and set a league record with a 1.57 earned-run average in 321 innings. He lost only six games, and at one juncture during the season, won 13 straight.

In 38 starts, Jansen recorded 31 complete games, even helped some by his stellar hitting. He batted .279 for the year, prompting manager O’Doul to not pinch-hit for him late in tight games.16

Jansen won his 30th game the last week of the season, outpitching Jack Salveson of the Portland Beavers 2-1 in an hour and 27 minutes.17

The Seals had a working agreement with the New York Giants. A couple of Seals pitchers the Giants had acquired in recent years had not panned out, so even after Jansen’s tremendous year, they were reluctant to deal for him. But trusted Giants scout Hank DeBerry swore that Jansen was as ready for the majors as anyone he had ever seen.18 Lefty O’Doul also told the Giants that Jansen was a can’t-miss prospect.19 As a result, the Giants traded Bob Joyce, who had won 31 games for the Seals in 1945 but had been a bust for the ’46 Giants, pitcher Jack Brewer, and infielder Dick Lajeski to the Seals for Jansen.20

Giants owner Horace Stoneham soon wired Jansen that he wanted to talk to him about contract terms. The Jansens had no telephone so he wired back that Stoneham should call the local drugstore and they would fetch him.21

Although one would expect the 26-year-old would be excited to finally have a chance to pitch in the big leagues, he in fact held out for more money than the Giants first offered him. His contract with the Seals provided for him to get a percentage of the sale price if he was sold to a big-league club, but because he was traded to the Giants, he received no remuneration. Then the Giants’ first contract offer was for little more than he made in San Francisco.22

Jansen eventually signed and reported to spring training in Phoenix a couple of weeks late amid reports that he was the best Giants pitching prospect since Carl Hubbell and Hal Schumacher.23 Then on March 11 disaster struck in his first spring-training game, against the Cleveland Indians in Tucson. Bob Feller was his mound opponent; batting in the second inning, Feller hit a line drive right back at Jansen, who in the split-second he had did not find the ball against a sea of white shirts behind home plate. The ball smashed into his cheekbone, breaking it and just missing his optic nerve before it caromed off into right field.24

Although stunned and injured, Jansen impressed manager Mel Ott and his new teammates by groping around on his knees looking for the ball to try to throw Feller out.25 Bill Rigney, who was playing shortstop that day, had a slightly different recollection. Rigney remembered that when he got to the mound, Jansen said, “Rig, get it out, get it out,” thinking that the ball was still in his face.26

The injury sidelined Jansen until near the end of spring training. When the season began, Ott used him sparingly in relief, with middling success. After an April 26 appearance, he didn’t see the mound for two weeks and was pretty certain that he would be sent out when the Giants had to trim their roster to 25. But Hank Gowdy, the Giants’ bullpen coach, took a liking to Jansen and persuaded Ott to give Larry a start, particularly since he had never been a relief pitcher.27

As a result, Jansen got his first start on May 10, when the season was about three weeks old. He responded with a complete-game 2-1 win over the Boston Braves at the Polo Grounds, scattering six hits and allowing no walks on only 96 pitches.28 After that performance, Jansen was in the rotation, quickly becoming the Giants’ most dependable pitcher. He seemed to get stronger as the season wore on and between July 5 and September 5 won 10 consecutive games. He then was victorious in 10 of his final 11 decisions to finish with 21 wins against only five defeats. Jansen led the league with an .808 winning percentage and the fewest walks per nine innings, finished tied for second in wins and third in complete games with 20. His 3.16 earned-run average was almost a full run under the league average.

Jansen’s stellar rookie season had a lot to do with the Giants winning 20 more games than they had in 1946 and moving from the National League cellar to fourth place.29 That year was the first that the Baseball Writers Association of America gave a Rookie of the Year Award. Any other year Jansen would have been a shoo-in but this time he finished second to Jackie Robinson, who had broken baseball’s color line that year and helped lead the Brooklyn Dodgers to the pennant. Still, the margin was relatively close, 129 points to 105.

When the 1948 Giants got off to a slow start, the front office fired Mel Ott and brought in fiery Leo Durocher to replace him. Although Durocher revamped the Giants, replacing power with speed and defense, he recognized that he had an ace in Jansen, stating publicly that he was “my kind of pitcher,” and trotted him out to start every four or five days as well as twice on two days’ rest.30 Jansen started 36 games and finished 18-12 in 277 innings, second most in the league. His win total was the third highest and he allowed the fewest walks per nine innings, cementing his reputation as a great control pitcher.31

Jansen also soon earned a reputation for being cool, calm, and collected on the mound, no matter what the situation.32 Not surprisingly, however, although he generally got along with Durocher,33 he sometimes came into conflict with his manager, who was an inveterate second-guesser. Jansen recalled that once Hank Sauer of the Cubs, who always hit him well, hit a home run early in a game in Wrigley Field.34 When Jansen came to the dugout at the end of the inning, Durocher asked what he had thrown Sauer. When Jansen answered that he’d thrown him a curveball low and away, Durocher said, “Next time throw him a fastball.”

On Sauer’s next at-bat, Jansen threw him a fastball and he smashed it so hard that it carried over the fence and onto the roof of a house across the street. When he got back to the bench, Jansen told Durocher, “He hit your pitch a helluva lot farther than he hit mine!”35

Early in his career, Jansen resisted Durocher’s attempts to have him brush hitters back occasionally, so they wouldn’t get too comfortable at the plate. According to one report, Durocher, in the midst of the heated Giants-Dodgers rivalry, ordered Jansen to throw at Roy Campanella of the Dodgers in an early 1951 game. When Jansen threw a first-pitch strike, Durocher started yelling at his pitcher from the dugout. When he threw a second-pitch strike, Durocher yelled to Jansen, “Remember, it’ll cost you a C-note.” Only then did Jansen throw inside, although he took something off the pitch.36

Later, in 1952, Jansen became involved in another beanball episode with the Dodgers. Apparently under orders from Durocher to hit Dodgers third baseman Billy Cox after a Giant was spiked in a play at second base, Jansen started to walk off the field. Durocher ordered him back to the mound and Jansen proceeded to plunk Cox in the back. National League President Warren Giles suspended Durocher for two days and fined him $100. He also fined Jansen $25, but remitted the fine because of the recommendation of the umpires and “his excellent conduct record.”37

With the Giants finishing in fifth place for the second year in a row in 1949, Jansen pitched in some bad luck and finished with 15 wins against 16 losses. His earned-run average climbed slightly to 3.85 and he led the league in home runs allowed, 36.

He bounced back in 1950 with 19 wins against 13 losses as the Giants improved to third place with an 86-68 record, just five games behind the pennant-winning Whiz Kids of Philadelphia. His 3.01 ERA was the fourth lowest in the league while his five shutouts tied for the league lead. In June Jansen threw three consecutive shutouts and tossed 30 consecutive scoreless innings in all.

Jansen allowed only 55 walks in 275 innings in 1950, which amounted to just 1.8 walks per nine innings, second stingiest in the league. At one point during the season he pitched 31 innings without allowing a walk. His catcher, Wes Westrum, remarked, “Catching Larry Jansen is like taking the day off. If I didn’t have to chase foul balls, I could sit in a rocking chair, his control is that good.”38

Jansen was named to the All-Star team for the first time in 1950, surprising for a pitcher of his stature, and had a marked impact in the National League’s thrilling 14-inning victory. At the All-Star break, Jansen sported a 9-5 record. He was coming off his worst outing of the year, however, having allowed eight runs, six earned, in 4⅔ innings against the Boston Braves on July 7. Nevertheless, before the All-Star Game, National League manager Burt Shotton had told Jansen that he was pitching three innings “regardless of what happens.”39

Jansen entered the game in the bottom of the seventh inning with the National League trailing 3-2. He proceeded to strike out six of the first nine batters he faced and allowed only one hit in five scoreless innings. After Ralph Kiner tied the game in the top of the ninth inning with a home run off Art Houtteman, Jansen retired the American League in the bottom of the ninth to send the game into extra innings. He thought his day was done. But Shotton badly wanted to beat the American League, which at the time had won 12 out of the 16 All-Star Games, including four straight. So he had Jansen hit for himself in the 10th inning (he struck out against Allie Reynolds), and kept him pitching through the 11th inning. Other than Larry Doby’s two-out single to center in the 10th inning, Jansen allowed only one other ball to the outfield, a fly out by Joe DiMaggio in the ninth inning.40

Afterwards Jansen, with usual modesty, remarked that he looked so sharp because the American League hitters didn’t know him very well. He also said, “I’d love to have a tape of those five innings.”41

Before the Giants’ magical 1951 season, Jansen had an appendicitis operation42 and then got off to a relatively slow start and stood only 5-5 after a loss to the Cardinals on June 4. But then he won seven out of nine heading into the All-Star break to bring his record to 12-7. He was again named to the All-Star team, but did not appear in the National League’s 8-3 victory. For the season, in addition to his 23 wins against 11 losses, Jansen placed fourth in strikeouts with 145 and second in fewest walks allowed per nine innings with only 56 allowed in 278 2/3 innings.

Jansen won three games during the Giants’ 16-game winning streak in August, but began to have back problems in late August. After throwing a 12-inning complete-game 5-4 win against the Cubs on the 27th, he didn’t start another game until September 7.43 On that day, although still suffering from back pain, he defeated the Boston Braves 7-3 in a complete-game 10-hitter.

Jansen’s grit hardly went unnoticed by his teammates. Catcher Sal Yvars said, “When you have a player of the importance of a Larry Jansen who is willing to play, it makes a big difference to a team. It’s another incentive to play harder. With all the big salaries today, you hardly find that attitude.”44

Jansen had publicly said, “I’m ready to pitch any time Leo gives the word.” Durocher took him at his word, announcing that for the rest of the campaign he was going with a three-man rotation of Sal Maglie, Jansen, and Jim Hearn, even if it meant pitching them only two days’ rest. And that is pretty much what he did, although Sheldon Jones did get some starts.45 Jansen certainly did his part, winning five of his last six starts.

Without Jansen’s clutch win on the last day of the regular season against the Boston Braves in Boston, the Giants would have finished in second place. Because of Jansen’s back trouble, Durocher told both him and Jim Hearn to warm up before the game.46 With the team trainer and team doctor looking on, Jansen felt no pain warming up and so took the mound.47 He gave up a run in the first, but Bobby Thomson tied it in the second with a home run. Jansen helped his own cause by leading off the third with a single and scoring the go-ahead run after singles by Eddie Stanky and Don Mueller.

The Giants added another run in the fifth as Jansen fairly cruised into the bottom of the ninth ahead 3-1. But Bob Addis led off the inning with a double to right field and Sam Jethroe pushed him to third with an infield single. Earl Torgeson forced Jethroe at second on a fielder’s choice as Addis scored to make it 3-2. Sid Gordon grounded into another force out at second, but Walker Cooper hit a Baltimore chop to third base for another infield hit. With two outs the tying run was on second and the winning run was on first. Durocher left the exhausted Jansen in the game to pitch to the hard-hitting Willard Marshall, a teammate from the ’47 record-setting Giants.48

After Marshall ripped a fastball foul down the right-field line, Jansen got him to hit a fly ball to Monte Irvin in short left-center field for the final out to keep the Giants in the pennant chase. Afterwards, Durocher told the press that “Jansen has a heart that weighs 190 pounds.”49

Jansen later related that during that stretch run the pressure was so intense and he was so exhausted and tired that he couldn’t sleep the night after pitching. He could get some sleep the next night but then the pressure of his next start would take hold and he would have trouble sleeping again for the two nights before his next start.50 In the best ballplayer tradition, Jansen also refused to change his ink-stained bedspread in his Henry Hudson Hotel room while the Giants were winning.51

Even though the final playoff game against the Dodgers was just three days after Jansen beat the Braves, Durocher told him that he would be the first guy in from the bullpen. Starter Sal Maglie got off to a shaky start, walking two and giving up an RBI single to Jackie Robinson, and Durocher got Jansen up in that first inning. But Maglie settled down until the eighth inning, when he gave up three runs to put the Giants behind 4-1. After Jansen pitched the scoreless top of the ninth, he sat next to Bobby Thomson on the bench when the Dodgers brought in Ralph Branca to relieve Don Newcombe in the bottom of the ninth. Thomson had hit a home run off Branca two days before, and so Jansen said to him, “Bobby, here comes your boy.”52

After Thomson’s blast into the left-field stands, Jansen initially felt “cold fear,” because he thought that the Giants had just tied the game, not won it. If that were the case, he would be taking the mound in the top of the 10th inning, and he “had nothing left in the tank.”53

After the Giants defeated the New York Yankees, 5-1, in the first game of the World Series behind Dave Koslo, Jansen started the second game in Yankee Stadium hoping to put the Giants up two games. Mickey Mantle led off and on the first pitch surprised the Giants with a drag-bunt single.54 Mantle eventually came around to score on a single to right by Gil McDougald. In the second, Joe Collins hit a wind-blown home run to right field to make the score 2-0 Yankees.55 Jansen then shut the Yankees out until the seventh when Ray Noble pinch-hit for him. In six innings of work he gave up only four hits and no walks, and struck out five, but was the losing pitcher in a 3-1 Giants defeat.

Jansen also started the pivotal Game Five in the Polo Grounds with the Series tied at two games apiece. After he threw two scoreless innings the roof caved in on him in the third. Uncharacteristically wild, Jansen walked two, gave up a run-scoring single to Joe DiMaggio, and then, after an intentional walk to Johnny Mize that loaded the bases, surrendered a grand slam to McDougald.56 Jack Lohrke pinch-hit for Jansen in the bottom of the third and his day was done as the Yankees went on to clobber the Giants, 13-1.

The next day Jansen pitched a scoreless eighth inning in relief as the Giants fell just short, 4-3, to lose the Series in six games. DiMaggio opened that inning with a ringing double to right-center field. McDougald tried to bunt DiMaggio over but Jansen pounced off the mound and threw Joe out at third.

That double was the last at-bat in DiMaggio’s storied career; he retired after the Series. Thereafter when Jansen would see him DiMaggio, Joe would say, “I got my last hit off you,” and Jansen would respond, “That’s all right. I got your last out.”57

As it was, 1951 turned out to be Jansen’s last stellar year as a big-league pitcher. His back issues became chronic and in 1952 he declined to an 11-11 record as his earned-run average rose to 4.09. He was able to log only 167 innings, over 100 fewer than the previous year, breaking his string of five straight seasons finishing in the top five in innings pitched in the National League. He was able to pitch only eight complete games in 27 starts.

The following year, 1953, Jansen began experiencing arm trouble to go with his bad back and fell to an 11-16 record in 184 innings. His earned-run average rose slightly to 4.14 and he could complete only six of his 26 starts as the Giants fell to fifth place.

Jansen was able to play only a small part in the Giants’ 1954 championship season. He continued to struggle with injuries, including a pulled groin and his chronically sore back, and pitched sporadically. Finally, on July 12 the Giants gave him his unconditional release and put him on the coaching staff. He finished with a 2-2 record and an unsightly 5.98 earned-run average in 13 appearances.

Jansen was interested in a coaching career but was not ready to stop pitching. He reported to the Giants’ 1955 spring training, pronouncing himself healthy and hoping to break back into the starting rotation.58 He was ineffective during the spring, but could have stayed with the Giants as a coach. On April 12 he signed with the Seattle Rainiers of the Pacific Coast League, however, to be closer to home and to continue pitching. He was also offered more money by the Rainiers than the Giants had offered him to coach, no small matter since he by then had seven children.59

Under manager Freddie Hutchinson, Jansen turned in a creditable 7-7 record in 26 appearances for the pennant-winning Rainiers. He tossed six complete games in 16 starts and walked only 26 in 137 innings.

Seattle welcomed Jansen back for 1956 and he seemed to revert to his old self. After starting the season 2-2, he won nine straight games, including a three-hit shutout against the San Francisco Seals. Instead of pitching every four or five days, he now threw about once a week, with great success. The Rainiers had a working agreement with the Cincinnati Redlegs and on August 5 the Redlegs, who were in a tight pennant race with the Milwaukee Braves, purchased his contract. He finished his time with Seattle with an 11-2 record and a sparkling 2.58 ERA in 24 games.

Jansen, who had beaten the Reds 24 out of 28 decisions while he was with the Giants, was thrown into the heat of the pennant race on August 10, starting against the league-leading Braves in Milwaukee. He didn’t disappoint, winning 8-1 in a complete game to pull Cincinnati to within a game of the lead.60 Typically, he struck out four and gave up no walks on 103 pitches.

He defeated the Braves again, 8-2, a week later in Cincinnati in another complete game. Jansen pitched eight scoreless innings after giving up a two-run first-inning home run to Eddie Mathews to bring the Redlegs to within 2½ games of the lead.61 Although no one would have guessed it at the time, it proved to be Jansen’s last major-league victory.

Although pitching just once a week seemed to be Jansen’s ticket to success, he wasn’t able to replicate the first two starts. He gave up six runs in five innings and lost to the Dodgers 6-4 in his next start, on August 24, as Cincinnati fell to third place, five games out of first. For the season, Jansen finished with a 2-3 record in eight appearances and seven starts. His earned-run average was an unsightly 5.19 for the Redlegs, who finished in third place, but only two games behind the pennant-winning Dodgers.

Jansen finished his major-league career with 122 wins against 89 losses for a .578 winning percentage in nine seasons. His earned run average was 3.58 in 1,765⅔ innings.

After his poor finish, Cincinnati returned Jansen to Seattle, where he restarted his coaching career in 1957 while continuing to pitch. He was reunited with Lefty O’Doul, now managing the Rainiers. Continuing to pitch once a week, Jansen won 10 and lost 12 with a solid 3.16 earned-run average for a fifth-place team. He walked only 25 batters in 180 innings.

Jansen hit a rare home run that year in Seals Stadium, one of only three he hit as a professional. When he came around third base, O’Doul, in the coach’s box, pretended to faint. The ball had carried over the center-field fence, where so few were hit that the Seals put a star with the name of the slugger on the fence to commemorate each ball that cleared the fence there. The next day Jansen asked Seals manager Joe Gordon where his star was. Gordon replied, “I don’t know where the hell that star’s gonna be, but I’ll tell you one thing: That pitcher’s gone to Fort Worth.”62

The 37-year-old Jansen moved his player/coach act to the Portland Beavers in 1958 in part to be closer to home. While still pitching once a week, he put together a 9-10 record in 22 appearances, of which 21 were starts, with a 3.13 earned-run average in 158 innings. He even took over the managerial reins in midseason from Tommy Heath after Heath injured his back, and guided the Beavers to a 78-76 record and a fourth-place finish.

The next two seasons Jansen remained with Portland as pitching coach and pitched sparingly but very well. In 1959 he was 1-0 with a 2.62 earned-run average in 24 innings of work. The following year he was even better, going 3-0 with a stingy 1.50 ERA in 18 innings.

The Beavers asked Jansen to manage the team in 1961 but he soon received a better offer. His old Giants teammate Alvin Dark had been hired to take over the San Francisco Giants and wanted Jansen to serve as his pitching coach. It was an offer he couldn’t refuse.63

It was also the beginning of an 11-year run for Jansen in San Francisco with three different managers. Early on, he helped developed Gaylord Perry and Juan Marichal. His general approach to coaching pitchers was that he was slow to try to change someone with talent.64 For example, he frequently said that the best thing he did with Marichal was to make sure he got in shape and stay out of his way.65 He taught the slider to Perry, working with him for a year and a half before he mastered it.66 When Perry was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1991, he singled out Jansen as the most important coach in his career.

Jansen slowly convinced Jack Sanford to pitch low in the zone rather than high and Sanford won 24 games in the Giants’ 1962 pennant year.67 Under Jansen’s tutelage, Billy O’Dell had his career year with 19 wins in 1962 while veteran Billy Pierce went 16-6. Marichal had his first big year with 18 wins.

Eleven years after another Dodgers-Giants playoff had resulted in the Miracle of Coogan’s Bluff, the Giants defeated the Dodgers for the pennant in a three-game playoff. It was full circle for Jansen, manager Dark, and coaches Whitey Lockman and Wes Westrum, who had all played on the ’51 Giants.

The Giants were always contenders in the 1960s but could not break through for another pennant. Jansen had his tenure as pitching coach interrupted on August 19, 1966, when he suffered a serious heart attack. He was hospitalized for almost three weeks but was able to make a full recovery and rejoin the team for 1967.68

The 1967 and 1968 Giants pitching staffs were particularly stingy, compiling earned-run averages of 2.92 and 2.71 respectively. Finally, after the 1971 season, the Giants fired Jansen. There was speculation in the press that his faith in the slider had finally gotten him crossways with Giants management.69 Jansen, however, attributed it to the fact that he often disagreed with the team’s rushing prospects to the majors, especially when they had not developed a third pitch, which Jansen believed was necessary for big-league success.70

Whatever the reason, Jansen was out of work for only a day before his old Giants manager Leo Durocher, now managing the Chicago Cubs, signed him as pitching coach for the Cubs for 1971.71 Jansen continued with the Cubs in 1972 after his old teammate Whitey Lockman became manager. He was welcome back for 1973 but decided, at 52 to retire from the rigors of baseball travel and stay at home with his family in Oregon.

After his retirement from baseball, Jansen entered the real-estate business and lived quietly with his large family in his hometown of Verboot. In his free time, he enjoyed golf, fishing, crabbing, and hunting. He and his wife, Eileen, often fished for salmon in Garibaldi, Oregon, where they kept a boat called 5 & 5 in honor of their five sons and five daughters.72

Larry Jansen died in Verboot on October 10, 2009, of congestive heart failure and pneumonia, three months shy of his 70th wedding anniversary. His wife, Eileen, died on September 1, 2012, also in Verboot. Together they were survived by their 10 children, 22 grandchildren, over 40 great-grandchildren, and three great-great-grandchildren.

This biography appears in “The Team That Time Won’t Forget: The 1951 New York Giants” (SABR, 2015), edited by Bill Nowlin and C. Paul Rogers III.

Sources

Anderson, Dave, Pennant Races – Baseball At Its Best (New York: Doubleday, 1994).

Baseball-Reference.com.

Dark, Alvin, and John Underwood, When in Doubt, Fire the Manager (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1980).

Dexter, Charles, “Pitcher’s Pitcher – Larry Jansen,” Baseball Digest, February 1951.

Dobbins, Dick, The Grand Old League – An Oral History of the Old Pacific Coast League (Emeryville, California: Woodford Press, 1999).

Dobbins, Dick, and Jon Twichell, Nuggets on the Diamond – Professional Baseball in the Bay Area From the Gold Rush to the Present (San Francisco: Woodford Press, 1994).

Eskenazi, Gerald, The Lip – A Biography of Leo Durocher (New York: William Morrow and Co., Inc., 1993).

Graham, Frank, The New York Giants – An Informal History of a Great Baseball Club (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1952).

Hirsch, James S., Willie Mays – the Life, the Legend (New York: Scribner, 2010).

Hodges, Russ, and Al Hirshberg, My Giants (New York: Doubleday and Co. Inc., 1963).

Irvin, Monte, with James A. Riley, Nice Guys Finish First – the Autobiography of Monte Irvin (New York: Carroll and Graf Publishers, Inc., 1996).

Jansen, Larry, clippings file, National Baseball Library.

Johnson, Lloyd, and Miles Wolff, The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, Inc., 1997, 2nd ed.).

Kahn, Roger, The Era 1947-1957 – When the Yankees, the Giants, and the Dodgers Ruled the World (New York: Ticknor and Fields, 1993).

Kelley, Brent, The San Francisco Seals, 1946-1957 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Co., Inc., 2002).

Kelley, Brent, “Larry Jansen: A Giant From Coast to Coast,” Sports Collectors Digest, November 1, 1991.

Kiernan, Thomas, The Miracle at Coogan’s Bluff (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Co., 1975).

Marshall, William, Baseball’s Pivotal Era, 1945-1951 (Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky, 1999).

Meany, Tom, Those Incredible Giants (New York: A.S. Barnes and Co., 1955).

Meany, Tom, Baseball’s Greatest Pitchers (New York: A.S. Barnes and Co., 1951).

Oakley, J. Ronald, Baseball’s Last Golden Age, 1946-1960 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Co., Inc., 1994).

Parker, Ev “Ace,” “Remembering Another Great Giant: Larry Jansen,” Napa Valley Register, November 20, 2009.

Peary, Danny, ed., We Played the Game – 65 Players Remember Baseball’s Greatest Era, 1947-1964 (New York: Hyperion, 1994).

Plaut, David, Chasing October – the Dodgers-Giants Pennant Race of 1962 (South Bend, Indiana: Diamond Communications, 1994).

Prager, Joshua, The Echoing Green – The Untold Story of Bobby Thomson, Ralph Branca and the Shot Heard Round the World (New York: Pantheon Books, 2006).

Richman, Milton, “Polo Grounds Papa,” Sport Life, October, 1952.

Robinson, Ray, The Home Run Heard ’Round the World – The Dramatic Story of the 1951 Giants-Dodgers Pennant Race (New York: Harper Collins, 1991).

Rosenfeld, Harvey, The Great Chase – The Dodgers-Giants Pennant Race of 1951 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Co., Inc., 1992).

Salin, Tony, Baseball’s Forgotten Heroes (Chicago: Masters Press, 1999).

Smith, Ken, “Larry Jansen, an All Weather Pitcher With Control,” Baseball Magazine, July 1948.

Snelling, Dennis, The Greatest Minor League: A History of the Pacific Coast League, 1903-1957 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2012).

Spalding, John E., Pacific Coast League Stars – Ninety Who Made It to the Majors, Volume II (Manhattan, Kansas: Ag Press, 1997).

Stein, Fred, Mel Ott – the Little Giant of Baseball (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Co., Inc., 1999).

Stump, Al, “Jansen’s the Joy of the Giants,” Sportfolio, July, 1948.

Szalontai, James, D., Close Shave – the Live and Times of Baseball’s Sal Maglie (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Co., Inc., 2002).

Testa, Judith, Sal Maglie – Baseball’s Demon Barber (DeKalb, Illinois: Northern Illinois University Press, 2007).

Thomson, Bobby, with Lee Heiman and Bill Gutman, “The Giants Win the Pennant! The Giants Win the Pennant! – The Amazing 1951 National League Season and the Home Run That Won it All (New York: Zebra Press, 1991).

Vincent, David, Lyle Spatz, and David W. Smith, The Midsummer Classic – The Complete History of Baseball’s All-Star Game (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2001).

Vincent, Fay, We Would Have Played for Nothing – Baseball Stars of the 1950s and 1960s Talk About the Game They Loved (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2008).

Wells, Donald R., The Race for the Governor’s Cup – The Pacific Coast League Playoffs, 1936-1954 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Co., Inc., 2000).

Zingg, Paul J., and Mark D. Medeiros, Runs, Hits, and Errors – the Pacific Coast League, 1903-58 (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1994).

Notes

1 In later years Irvin compared Jansen to Hall of Famer Tom Seaver. See Monte Irvin with James A. Riley, Nice Guys Finish First – the Autobiography of Monte Irvin, 154.

2 Later in the afternoon, the Dodgers defeated the Phillies 9-8 in 14 innings to again tie the Giants for the pennant. See Harvey Rosenfeld, The Great Chase – The Dodgers-Giants Pennant Race of 1951, 194-204; Russ Hodges and Al Hirshberg, My Giants, 104-108.

3 William Marshall, Baseball’s Pivotal Era, 1945-1951, 418.

4 Al Stump, “Jansen’s the Joy of the Giants,” Sportfolio Magazine, July 1948, 54; Milton Richman, “Polo Grounds Papa,” Sport Life Magazine, October 1952, 72.

5 Charles Dexter, “Pitcher’s Pitcher – Larry Jansen,” Baseball Digest, February 1951, 45.

6 Tom Meany, Baseball’s Greatest Pitchers, 131.

7 Marshall, 418.

8 Landis later reprimanded and fined the Red Sox $500. Stump, 54-55; Meany, 131-132; Dexter, 45; Tony Salin, Baseball’s Forgotten Heroes, 53-54; Ken Smith, “Larry Jansen, an All-Weather Pitcher With Control,” Baseball Magazine, July, 1948, 259; Unidentified article, August 1, 1940, from the Larry Jansen clippings file, National Baseball Library.

9 Dick Dobbins, The Grand Old League, 53; John E. Spalding, Pacific Coast League Stars, Volume II, 124.

10 Earlier sources have Jansen learning the slider from Woodall in 1941. Dexter, 45-46, Stump, 55 (“Woodall saved my neck. At first I couldn’t get the ball to break – it just spun – but he stayed right with me. Now it’s my best pitch.”). But Jansen’s later recollections have him learning the slider in 1942. Salin, 54; Brent Kelley, “Larry Jansen: A Giant From Coast-to Coast,” Sports Collectors Digest, November 1, 1991, 170

11 Spalding, 124; Dexter, 45; Stump, 55.

12 Kelley, 170; Dexter, 46.

13 Stump, 55; Kelley 170.

14 Kelley, 170; Brent P. Kelley, The San Francisco Seals, 1946-1957, 12-13; Salin, 54; Dexter, 46.

15 The Seals, managed by Lefty O’Doul, beat their cross-bay rivals the Oakland Oaks, managed by Casey Stengel, by four games for the pennant and then beat them in the finals of the Governor’s Cup four games to two. Lloyd Johnson and Miles Wolff, The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball (2nd ed.), 348; Donald R. Wells, The Race for the Governors’ Cup, 292-323. To capitalize on fan interest in the rivalry the teams began playing two-city Sunday doubleheaders in 1946, with a morning game in one city and an afternoon game in the other. Salin, 56.

16 Salin, 56.

17 Dick Dobbins and Jon Twichell, Nuggets on the Diamond, 173.

18 Ray Robinson, The Home Run Heard ’Round the World, 26; Bob Cooke, “Another Viewpoint,” undated New York Herald Tribune column in the Larry Jansen clippings file, National Baseball Library.

19 William F, Goodrich, “Lefty O’Doul Sold Giants on Jansen,” unidentified article dated July 1947 in the Larry Jansen clippings file, National Baseball Library.

20 Stump, 53.

21 Ray Robinson, The Home Run Heard ’Round the World, 24-5; Bob Cooke, “Another Viewpoint,” undated New York Herald Tribune column in the Larry Jansen clippings file, National Baseball Library.

22 Salin, 56.

23 Frank Graham, The New York Giants, 277.

24 John Ebinger, “Jansen’s Jaw Fractured; Giants Whip Feller, 8-3,” unidentified article dated March 12, 1947, in the Larry Jansen clippings file, National Baseball Library.

25 Meany, 129; Stump, 52; Dexter, 46-47; Richman, 72 .

26 Danny Peary, ed., We Played the Game – 65 Ballplayers Remember Baseball’s Greatest Era – 1947-1964, 28. While Jansen was waiting for an ambulance in the clubhouse after getting hit, outfielder Hank Edwards dislocated his shoulder diving for a ball. He needed an ambulance, too. The Giants’ medical personnel decided that Edwards was hurt worse than Jansen and so should take the first ambulance. Jansen was loaded onto the second ambulance but arrived before Edwards, whose ambulance had first gone to the wrong hospital. It turned out Jansen had a shattered cheekbone and was injured more seriously than originally thought. They operated right away and told him a half-inch higher and he would have lost the sight in his eye. Salin, 63-64.

27 Salin, 57.

28 Dexter, 47.

29 Of course, 1947 was also the year that the Giants set a major-league record by hitting 221 home runs. Jansen finished seventh in the MVP voting that year.

30 Dexter 47; Fay Vincent, We Would Have Played for Nothing, 42-43.

31 He had finished second to Preacher Roe in fewest walks allowed per nine innings in his rookie year and was second both years in home runs allowed.

32 Richman, 23.

33 Judith Testa, Sal Maglie – Baseball’s Demon Barber, 204.

34 Only Ralph Kiner, with 12 career home runs off Jansen, hit more.

35 James K. McGee, “Jansen a Tale-Spinner,” San Francisco Examiner, March 20, 1969, 50.

36 Kiernan, 63-64. Much later Jansen recalled the incident but disputed being told to throw at a batter under the threat of a fine. Rosenfeld, 20. But later in his career Jansen seemed to buy into Durocher’s two-for-one rule: two opposing batters plunked for every one Giant hit. Monte Irvin with James A. Riley, 169.

37 Giants pitcher Monte Kennedy was also fined $25 for throwing at Gil Hodges and Joe Black earlier in the game. His fine was not remitted. “Kennedy, Jansen Also Penalized in ‘Bean Ball’ Case,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, September 10, 1952.

38 Dexter, 47. Another Giant catcher, Sal Yvars, expressed the same sentiment, saying, “You could catch him in a rocking chair.” Joshua Prager, The Echoing Green, 206.

39 Salin, 58; Kelley, 172.

40 The National League eventually won the game on a 14th-inning home run by Red Schoendienst off Ted Gray. Ewell Blackwell pitched the final three innings for the National League and was the winning pitcher. David Vincent, Lyle Spatz, and David W. Smith, The Midsummer Classic – The Complete History of Baseball’s All-Star Game, 105-110; Meany, 133-34.

41 Robinson, 26.

42 Robinson, 26-27.

43 Jansen did make a two-inning relief appearance against the Pirates on August 30 and ended up being the losing pitcher in a 10-9 loss.

44 Rosenfeld, 125.

45 Rosenfeld, 125.

46 Thomas Kiernan, The Miracle at Coogan’s Bluff, 230-31.

47 Salin, 59.

48 Rosenfeld, 195. Some accounts have Durocher visiting the mound before Cooper batted and Jansen talking him into staying in the game. Kiernan, 124; Robinson, 201. Rosenfeld disputes that Durocher came out to the mound.

49 Rosenfeld, 195.

50 Jansen said all the Giants’ starting pitchers were exhausted, including Sal Maglie, Jim Hearn, and Dave Koslo. Kiernan, 114.

51 Dave Anderson, Pennant Races – Baseball At Its Best, 242.

52 Kelley, 172.

53 Ev “Ace” Parker, “Remembering Another Great Giant: Larry Jansen,” Napa Valley Register, November 20, 2009.

54 According to Jansen, none of the Giants’ scouting reports indicated Mantle would drag bunt, so it came as a complete surprise. Kelley, 172; Roger Kahn, The Era – 1947-1957, 296.

55 Wind-blown at least in Jansen’s recollection. Kelley, 172.

56 DiMaggio had advanced to second and Yogi Berra to third on an error by right fielder Clint Hartung, leaving first base open.

57 Kelley, 172.

58 Barney Kremenko, “Jansen, Arm OK, Hopes to Win 15 in Comeback,” unidentified article dated March 20, 1955, in Larry Jansen clippings file, National Baseball Library.

59 “Jansen Quits Giants to Pitch on Coast,” unidentified clipping dated April 13, 1955, in Larry Jansen clippings file, National Baseball Library.

60 “Redlegs Hail Win by Jansen,” unidentified clipping dated August 11, 1956, in Larry Jansen clippings file, National Baseball Library.

61 Earl Lawson, “Redlegs’ Jansen Again Whips Braves,” Cincinnati Times-Star, August 18, 1956

62 Kelley, 171.

63 Salin, 61-62; Walter Judge, “Larry Jansen Replaces Posedel as Giant Coach,” San Francisco Examiner, November 11, 1960.

64 Kelley, 171.

65 David Plaut, Chasing October – The Dodgers-Giants Pennant Race of 1962, 112; Art Rosenbaum, “Eleven Years in the Bullpen,” San Francisco Chronicle, November 5, 1971; Salin, 62.

66 Harry Jupiter, “Jansen Gets Credit for Giants’ Pitching,” San Francisco Examiner, September 12, 1966.

Full Name

Lawrence Joseph Jansen

Born

July 16, 1920 at Verboort, OR (USA)

Died

October 10, 2009 at Verboort, OR (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.