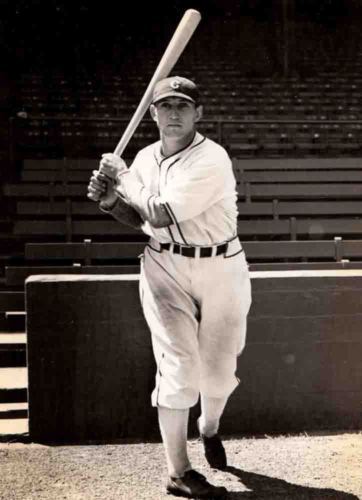

Larry Rosenthal

Larry Rosenthal was a product of the Depression-era Middle West America who found his way to the major leagues through amateur baseball . . .the “sandlots.” He was a left-handed-hitting and throwing outfielder who had eight seasons in the American League and another nine in the high minors, mostly in the American Association.

Larry Rosenthal was a product of the Depression-era Middle West America who found his way to the major leagues through amateur baseball . . .the “sandlots.” He was a left-handed-hitting and throwing outfielder who had eight seasons in the American League and another nine in the high minors, mostly in the American Association.

In the Twin Cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul, beginning from the early 20th Century through the 1950s, amateur baseball was nourished by the presence of two outstanding professional teams, the Millers and the Saints of the American Association. There were three high-caliber amateur leagues in St. Paul alone, many more spread though the outlying towns in Minnesota, and this was representative of what was going on all around the country. Contemporary newspaper accounts tell of crowds of eight and ten thousand fans huddled around the fields at Como or Dunning fields in St. Paul to watch a crucial game in the city leagues, and a crowd of 12,000 at Lexington Park, the Saints’ home field, to watch the amateur playoffs. The Saints, for one, to whom a paying gate of 7,500 was a bonanza, were following this closely.

Lawrence John “Larry” Rosenthal was born May 21, 1910, in St. Paul, along with his twin sister, Florence, into a Polish Catholic family living in the blue-collar Frogtown district. As its name implies, this area of the city was inhabited by descendants of the early French settlers in the 1850s but more recently by immigrant families from eastern and southern Europe. Larry’s father, John, worked in a shoe factory in the city, and his parents had emigrated from Poland, at which time the family name had been changed to Rosenthal from Rozentawa, its Polish equivalent. Larry grew up playing ball in the sandlots and school teams because baseball is what every kid wanted to play then, with a little time for football and handball, in which he was a city tournament player.

After graduating from St. Agnes High School in a commercial course, Rosenthal worked as a clerk in a business that sponsored one of the hot amateur teams in the best baseball league. By the time he was 20, he was starting to get some coverage in the local papers for his feats on the ball field, both as a hitter and left-handed pitcher for one of the leading teams. A full page of the St. Paul paper’s sports section was devoted to the box scores, standings, averages, and write-ups of the big games. One selection showed Rosenthal hitting .447, leading his team, and contributing several mound victories.

Bob Connery, the general manager of the St. Paul Saints, kept a keen eye out for local talent and noticed how much ground Rosenthal could cover in the outfield, as well as his throwing arm and line-drive bat. Rosenthal was invited to the Saints’ spring-training camp in 1933, along with other local amateur stars Angelo Giuliani, Les Munns, Gene Trow, and Gene Corbett. All but Trow would eventually play in the big leagues.

By this time Rosenthal had matured into a 180-pound six-footer, very fleet and with defensive skills that put him ahead of all the outfielders on the Saints. The hitting could come later, thought Connery, who signed Rosenthal and persuaded manager Emmett McCann to put him in center field as often as possible. A bit old for a novice pro ballplayer at 23, Rosenthal fit into an outfield of Ben Paschal, a member of the 1927 New York Yankees Murderer’s Row team, Jesse Hill, and Rip Radcliff and did well for a sandlot star, hitting .294 in 74 games. The St. Paul fans absolutely loved him. Here was one of their own, right off the local ball fields, showing up the established pros with his fancy fielding and timely hitting. His boyhood nickname of “Bud” was now replaced with the more endearing “Rosie” by the fans and picked up by the papers. It was all new and wonderful to Rosenthal, who fortunately had the maturity to handle it.

One time though, Rosenthal recalled, he was a bit disappointed with his write- up in the paper. Columbus was in town with its powerhouse team and Paul Dean, hard-throwing younger brother of Dizzy, was pitching. In the middle innings of a 1-1 game Rosenthal hit his first professional home run over the left-center field wall of Lexington Park onto the roof of the Coliseum Ballroom that bordered Lexington Avenue. It proved the margin of victory in a one-run game. But the headline over the next day’s write-up said, “Munns Outpitches Dean, Saints Win 2-1,” with no mention of his home run except in the box score.

In 1934, Rosenthal’s second year with the Saints, a new manager, Bob Coleman, attempted to alter his batting to produce more power. The result was a .253 batting average with 94 strikeouts. Seldom in his career did his walk total fall below strikeouts, and at the end of a dismal season for both Rosenthal and the Saints, the hitting experiment and the manager were shelved. The following year Rosenthal bounced back with a .302 batting average, 35 doubles, 13 home runs, and 90 walks, which was second in the American Association. He also set a league record for outfield putouts that lasted for many years.

The 1936 season saw big events gathering on Rosenthal’s horizon. He entered the year with the Saints as one of the most promising young players in the league. Four weeks into the season he was hitting in the .390 range, and was just edged out of the American Association lead in the batting race on May 15th. Speaking of age, it should be noted here that somewhere between the time he came up with the Saints and when he was touted as a highly regarded major-league prospect, he lost two years in age. The 1934 Saints roster lists Rosenthal as having a birth year of 1912, instead of the correct 1910 date. This error was carried all the way through his career, and through the early Macmillan encyclopedias, until about 1987. Therefore, he was 26 (not 24 as everyone thought) on June 4, 1936, when it was announced that the Chicago White Sox had purchased Rosenthal from the St. Paul Saints, where he was hitting .331 after 65 games.

Most of Rosenthal’s major-league service, four full seasons and parts of two others, was spent with the White Sox, the team he would be most identified with. He arrived as a much-touted rookie, saw lost opportunities his second and third years though nagging injuries that cost him a starting job, had some sizzling batting streaks and even longer dismal slumps at the plate, and above all, was very highly rated as an outfielder. He joined a capable third-place team, usually winning from 81 to 86 games a year, which was anchored by future Hall of Famers Luke Appling and Ted Lyons with the peppery Jimmy Dykes as player-manager. Former Saints teammates Monte Stratton and Rip Radcliff were there, and later Johnny Rigney and Hank Steinbacher came up from the Saints.

After watching from the bench for a couple of weeks after his arrival, Rosenthal made his major-league debut on June 20, 1936, as a pinch-hitter. He doubled to the left-center field wall in Comiskey Park off Harry Kelley of the Philadelphia Athletics in the ninth inning and scored the only Sox run two batters later in a 2-1 loss. The next day Rosenthal was inserted in the starting lineup in center field and immediately began one of those batting tears, getting 14 hits in his first 29 at-bats, sewing up the starting job for rest of the 1936 season. He finished the year with a respectable .281 batting average with 59 walks in 85 games and with his speed was a good candidate for leadoff or second hitter.

Rosenthal began the 1937 season as the White Sox’s starting center fielder, batting leadoff or second, but he had trouble getting started hitting. Just as his hitting picked up, he injured muscles in his leg rounding first in a game on May 11. It was two months before he could play again and then only on a limited basis for the rest of the season. Rosenthal tied Goose Goslin of the Detroit Tigers for the league lead in pinch hits with nine. The following season proved just as frustrating, with another leg injury unrelated to the first, which sidelined him for nearly the whole season. He hit .289 and .286 in these two years, with barely 100 plate appearances each season.

In between those seasons, Rosenthal married 22-year-old Ruth Eder of Duluth, Minnesota, in November 1937. Their only child, Janet Ruth, was born in 1940.

A healthy Larry Rosenthal returned to the White Sox in 1939 but found it tough to break into a .300-hitting outfield. His friend Mike Kreevich had taken over the center-field spot and hit .324. Rosenthal was put in for the slumping Rip Radcliff and then for Gee Walker as Walker’s hitting tailed off. Rosenthal was a vast improvement defensively over whomever he replaced, and the entire pitching staff wanted to see both Rosenthal and Kreevich out there. Here is where some politics came into play as Rosenthal indicated that the pitchers and coach Billy Webb were in his corner, while another coach, Muddy Ruel, was an antagonist. Rosenthal and Ruel never got along well, and the two coaches were always trying to get the ear of manager Jimmy Dykes about playing Rosenthal in the field, one for, the other against.

Playing in 107 games, Rosenthal turned in some healthy numbers considering he played just two-thirds of the time: 21 doubles, 5 triples, 10 home runs, and 51 RBIs. His batting average slipped to .265, but his fielding average of .990 was third in the league for outfielders playing 80 or more games. One of his home runs in 1939 came off Cleveland’s Bob Feller, inside the park at Comiskey Park. “As soon as I hit it, I thought I had a good chance for four bases,” Rosenthal said about the hit, which bounced off the brick wall in center field 440 feet away.

The 1940 season was Rosenthal’s best for batting average, .301 in 107 games, and throwing in his 64 walks gave him a very good on-base average of .432, better than New York’s Joe DiMaggio, who came in at .425 although he led the league in batting average.

Rosenthal had played in only a handful of games in 1941 when he was sold by the White Sox to Cleveland, where he saw more limited service, mostly as a late-inning defensive replacement. One highlight of this season was the game in which the Indians stopped DiMaggio’s 56-game hitting streak. Rosenthal entered the game as a pinch-hitter and cut the Yankees’ lead to 4-3 by driving in two runs with a triple, although the Yankees hung on to win the game.

With a twinkle in his eye, Rosenthal related the following story, which occurred shortly after the White Sox had sold him to the Indians: “Ted Williams came up to me before a game and said ‘You probably don’t have any more loyalty to the White Sox after they let you go. Tell me what they discussed about pitching to me.’” One can only imagine Williams filing this information away in his head along with all the rest he picked up.

The 1942 season brought significant changes for Rosenthal, as well as all of the other ballplayers, with everyone affected by World War II. In the early part of the war, all draft-eligible men were considered likely to be called into military service, and even though Rosenthal was married with a dependant child born before 1941, it seemed he might be drafted. His draft status, though, went from 1-A to 4-F after a physical exam later in the war showed arthritis in his legs. He would then become a desirable wartime commodity in baseball, someone who wouldn’t be drafted.

Rosenthal spent spring training with the Indians, and on the train heading north he was told that he had been traded to Kansas City of the American Association, so it was back to the minor leagues after changing trains at an interim stop. It didn’t exactly come as a surprise to Rosenthal since Lou Boudreau, the Indians’ new manager, hadn’t spoken to him at all in spring training. Kansas City was a Yankees farm team, and Rosenthal joined many other farm hands who would, like him, also see service with the parent organization during the war years. Early in the season Rosenthal collided with teammate Harry Craft, resulting in yet another injury for him, and upon returning a batting slump kept him from contributing as much as he might have to the pennant-winning Blues. The Yankees still found Rosenthal of value for the following year, as George Weiss assigned Rosenthal to the Newark Bears of the International League, another Yankees farm team, in 1943.

Rosenthal elected not to report to Newark until given better assurances and a contract inducement, so he missed a lot of spring training. As a result, he was hitting .240 until July 1, but he suddenly caught fire to hit .340 for the rest of the season and help the Bears to a second-place finish and a berth in the playoffs. His great finish gave him a .272 average with 11 home runs, and his 78 RBIs were second on the team only to Ed Levy’s 81. He also walked 98 times, third in the league.

Rosenthal was to go with Newark in 1944 for spring training but he elected not to report, deciding instead to sit home until he heard one way or the other from the Yankees. He had a defense-related job, working in security for the military facility at the St. Paul airport.

The strategy worked. He was told to report to the Yankees’ training camp at Atlantic City, New Jersey, and he ended up making the team. Larry Rosenthal was now a Yankee. However, the abbreviated stay in training camp (he reported fewer than 10 days before the regular season opened) gave him little chance to develop his batting eye. Never a spring hitter, he started the season in a slump. With a .198 batting average in 101 at-bats in June, Rosenthal was reassigned by the Yankees to Newark. For the second time in fewer than three months, Rosenthal refused to report to Newark, giving the Yankees little choice but to sell him to the first taker. The Philadelphia Athletics purchased his contract, and the holdout strategy worked again as Rosenthal was able to stay in the majors.

The A’s, managed by venerable Connie Mack, was a team primarily comprised of youngsters and 4-F players, along with veterans Dick Siebert, Bobo Newsom, and player-coach Al Simmons, who often invited Rosenthal as his after-hours companion on the town. Rosenthal was suffering the effects of an outfield collision with Johnny Lindell, which had occurred early in his stay with New York, so he was able to get into only 32 games with the A’s, mostly as a pinch-hitter or late-inning substitute in the outfield.

The Yankees were going for their fourth straight pennant and were in a three-way race with the Detroit Tigers and St. Louis Browns going into the last month of the season, with a different team in first place almost every day. In late August, Philadelphia hosted the Browns and won two of three games, with Rosenthal hitting a ninth-inning pinch-hit double off Bob Muncrief for a one-run victory in one of the games.

A few weeks later, the Athletics traveled to New York and took the opener of a three-game series against the Yankees. The stage was set for a Sunday doubleheader, and 55,000 people crowded into Yankee Stadium on a beautiful day with Rosenthal occupying his usual place on the bench. In the first game the Yankees’ Ernie Bonham baffled the young A’s hitters with his sinker ball and had a 4-3 lead entering the ninth inning. Rosenthal had noticed something in Bonham’s delivery, that he was tipping off his pitches. Rosenthal brought it to the attention of Al Simmons, who confirmed it. However, the kids on the A’s were too inexperienced to take advantage of it. The first A’s batter in the ninth singled, and as fate would have it, Connie Mack looked down the bench to Rosenthal, and called him over. Rosenthal recalled, “Mr. Mack said to me ‘Now Mr. Roosevelt, we don’t want these Yankees winning any more pennants, so I want you to go up there and hit a home run.’” Mack sometimes did a whimsical play on players’ last names, so Rosenthal became Roosevelt, and Dick Fowler was Mr. Flowers, etc. Mack had Rosenthal hit for George Kell, and Rosenthal selected one of Bonham’s fastballs and lined it into the right-field stands. The two-run homer gave Philadelphia a 5-4 win, and the A’s took the second game, as well.

The sweep of the Yankees in that series was highlighted by the Rosenthal home run and was the death knell of the Yankees’ pennant hopes for 1944. The delicious irony of a cast-off delivering a fatal blow was not lost on the field personnel, as Yankees coach Art Fletcher later told Rosenthal, “[Yankees manager] Joe McCarthy complained that of all the guys to beat us, it had to be you.” Fletcher also indicated that McCarthy disappeared into his hotel room with a bottle of scotch for a prolonged time. Sportswriters had a field day with it, as Dan Daniel mentioned it at least twice in his syndicated column, and Shirley Povich did, as well.

Rosenthal was given a chance in the Philadelphia A’s outfield in 1945, but by this time many players were returning from service, and his low draft status was no longer a factor in being on a big-league roster. He was sold to Milwaukee in the American Association, where he batted .303 in 74 games. In December 1945 Rosenthal became property of the team where he had started, the St. Paul Saints, which was by then a Brooklyn Dodgers farm team. He hit a solid .278 in 135 games for the Saints in 1946, and the following season, which was split between the Saints and Indianapolis, Rosenthal had a banner year, hitting .320.

In 1948, Rosenthal’s professional baseball career came to an end after 16 seasons, and he also suffered financial reverses owing to misfortune in investments. All this would pale in comparison to the most devastating of personal tragedies, the death of a spouse late in the year.

Rosenthal began the season with New Orleans in the Southern Association but left the team after playing 39 games, hitting .268 with three home runs. The heat and humidity were hard on his body of 38 years, but there was another problem at home requiring his attention. He had invested considerable savings in breeding pairs of mink with a local fur ranch, which interestingly had a quarter-page ad in the St. Paul Saints’ programs in 1948, touting their fur line for breeders and pelts at $600 a breeding pair. Unfortunately, an infectious strain called the Aleutian virus wiped out almost all of the breeding minks in 1948. Rosenthal had lost all his investment. Manager Nick Cullop of Milwaukee called Rosenthal to help out in the outfield for the rest of the season, and he played 34 games with the Brewers to finish out his professional career.

In October Rosenthal’s wife, Ruth, entered a St. Paul hospital with a sudden onset of an internal organ disease, from which she died after three weeks. She was 32, and, besides Larry, left an eight-year-old daughter, Jan.

Now out of professional baseball, Rosenthal began the second half of his life as a single father and found work driving a truck for Schmidt Brewing Company in St. Paul, where he was employed for several years. In 1949 he was asked to play ball with the Winona Chiefs in the Southern Minnesota League, one of the premier amateur-semiprofessional leagues in the country. Rosenthal was 39, but he still batted .379, good for sixth in the league that season. Rosenthal retired from the Winona team at the age of 40 the following season, but he played some more amateur ball with the West St. Paul team in a city league for a couple of additional years. About this time Rosenthal married his second wife, Patricia, and this marriage ended 20 years later in divorce.

Rosenthal began working at the Mobil Oil Company’s barge terminal in St. Paul, driving trucks from the terminal to Mobil’s customers. He worked there for 20 years, retiring in 1978. Rosenthal worked next for the Commercial State Bank in downtown St. Paul, where one of his duties put him in charge of customer parking. Here Rosenthal found that in addition to the many old baseball fans who not forgotten him, many younger fans now collecting baseball memorabilia also knew of Larry Rosenthal. About this time a retired address directory of major-league players came out, and Rosenthal began getting many more letters from fans than previously, several a week requesting an autograph, signed pictures, and information about him. He had baseball cards printed up with the help of noted sports artist Ken Haag, who was a friend and an avid St. Paul Saints fan going back to when Rosenthal played. There were interviews published in two local St. Paul neighborhood newspapers, and the St. Paul Pioneer Press did a nice article on him in 1981, as well as the Sports Collectors Digest in 1984.

Rosenthal was a guest at the local Society for American Baseball Research chapter meeting in 1985, and he was always acknowledged at the annual Hot Stove League banquets, which he regularly attended, in St. Paul. He was proud of his baseball experience and always found time to talk about the game, his observations, and the many players he both played with and against, some of whom were among the very best to have played the game. Rosenthal died after a four-year illness in 1992 at 81, leaving his daughter Jan, four grandchildren, and four great-grandchildren.

Note

A version of this biography appeared in the book Minnesotans in Baseball, edited by Stew Thornley (Nodin, 2009).

Source

Larry Rosenthal file at National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York.

The Baseball Encyclopedia, Macmillan, 1969, 1976.

Official Baseball Guides: Reach and Spalding 1934-1939, Spalding-Reach 1939-1941, The Sporting News 1942-1949.

Who’s Who in the American Association, F. P. Hutchinson, 1935, 1936, 1947.

The Sporting News, various articles, 1933 to 1948, accessed on line through Paper of Record.

Chicago Tribune, various articles 1936-1940, accessed on line through ProQuest at the St. Paul Public Library.

St. Paul Pioneer Press, various articles 1930 to 1992.

New York Times, September 18, 1944, p. 12.

D. A. Sadoff, Doctor of Veterinary Medicine

Mrs. Janet Miller (subject’s daughter), personal interviews, 1990-1993.

Scrapbook compiled in the 1930s by a friend of Larry Rosenthal.

Numerous interviews with the subject, 1982-1992.

Full Name

Lawrence John Rosenthal

Born

May 21, 1910 at St. Paul, MN (USA)

Died

March 4, 1992 at Woodbury, MN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.