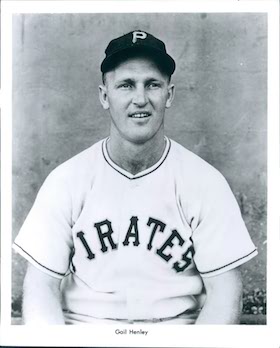

Gail Henley

Tenacity and zeal were hallmarks of Gail Henley’s game, which along with stellar baseball skills fueled a rapid rise to the major leagues and engendered high regard from renowned talent evaluators. That tenacity and zeal also played a part in making his big-league career much shorter than expected.

Tenacity and zeal were hallmarks of Gail Henley’s game, which along with stellar baseball skills fueled a rapid rise to the major leagues and engendered high regard from renowned talent evaluators. That tenacity and zeal also played a part in making his big-league career much shorter than expected.

The native of Wichita, Kansas, developed a desire for baseball at a young age. His hometown did not have organized youth programs, so boys who were anxious to play ball flocked to an area known as Matheson’s Pasture. There, teams were assembled and games were played based upon ability rather than age. For that reason, the young Henley often found himself playing with and against boys who were two and three years older. 1

Henley was born on October 15, 1928, the son of James and Dorothy Henley. His father was a butcher and later ran a market. Gail had two younger sisters. In 1939, when he was 10, Henley’s family moved to Southern California. They settled in Inglewood, 12 miles southwest of downtown Los Angeles. By the time Henley had enrolled at Inglewood High School, his skills had made him one of the finer athletes in the area. Through four years at the school, the blond, athletic teen shone in basketball and football. He was all-CIF (California Interscholastic Federation) as a catcher in baseball, and when the track coaches needed a speedster for their relay team, they recruited Gail Henley.

In the decade after World War II, amateur baseball flourished around Southern California. On Sundays throughout the year, semipro games were played in almost every park from Sherman Oaks in the north to Long Beach in the south. Henley and his buddies, Bill Lillie and Al Wilson, among others, were in demand with coaches and kept busy with a dizzying schedule of games.

It was during the summer between Henley’s junior and senior years of high school that football began to tug at the talented athlete. The Inglewood High football coach, Bob Winslow was casting about for a college coaching job. When he felt certain he was about to be hired at Colgate University, he encouraged Henley to follow him east. Winslow was instead hired to coach ends at the University of Southern California and almost immediately cast a recruiting net for his former standout.

As a high school senior, Henley’s play at quarterback and right halfback helped Inglewood to reach the CIF playoffs. He agreed to attend USC but encountered a hiccup. Administrators determined that he would first have to boost his grades, and coaches steered him to Modesto Junior College. The necessary academic work took only one semester to complete, and in January 1947 Henley enrolled at USC on a football scholarship. What he observed very quickly changed the course of his life.

The USC program was swelling with student athletes just out of the military and back from World War II. Many were six to eight years older and up to 30 pounds heavier than the 17-year-old Henley. In the spring he decided instead to try out for the Trojans baseball team. It was a daunting challenge. More than 100 hopefuls took part. Henley had a triple-digit number pinned to his back. Each day more and more numbers were called, and the players assigned to them were cut. By the end of the tryout, Henley had made the team.

Football did not cease quietly. When the Inglewood product failed to show up for the start of spring football drills, Jeff Cravath, the Trojans’ head coach, stomped onto the baseball diamond to confront Henley. “What the hell are you doing here?” Cravath barked. “You came here to play football!” When Henley replied that he wanted to play baseball, Cravath snapped, “You have your ass on the football field tomorrow, or else!” The next morning after a meeting between Cravath and Sam Berry, the USC baseball coach, an understanding was reached. Henley’s football playing days were over. The decision left his former high-school coach incredulous. “You had it made! You were third team and you hadn’t even put on a uniform yet.”

A year later Henley’s skills helped fuel USC to the national championship. The sophomore outfielder batted over .400 for the season. In only the second year of the College World Series, the Trojans defeated the Yale Bulldogs and their first baseman George Bush to claim the crown. While Henley’s teammates celebrated and traveled back to Southern California, the fleet outfielder was on his way to Minneapolis. He had struck a deal with the New York Giants’ area scout, Dutch Ruether, on a three-year Triple-A contract. Fresh from winning college baseball’s national championship, the 19-year-old was playing at the top level of the minor leagues.

Henley’s stay with the Minneapolis Millers was a short one, however – one week. Without ever getting into a game, he was dispatched to the Giants’ farm club in the Class A Western League, the Sioux City Soos. Almost instantly, the College World Series standout got on the wrong side of his manager, Joe Becker. Henley had been instructed to phone Becker as soon as he arrived at the team’s hotel. He followed those instructions to the letter. The 6:00 A.M. call drew the ire of the Soos’ boss, who was awakened from a restful sleep.

There were also men in baseball at that time who were not enamored with college players. “The mustard was all over me,” admitted Henley, who explained that he felt his tales of college ball and College World Series success grated on his manager. A slow start certainly didn’t do anything to improve things. “The first nine games I went oh-for-five. I struck out my first three times. They didn’t have a good selection of bats, and I was swinging a 35-inch, 35-ounce Babe Ruth model that I was not comfortable with,” Henley said.

When Henley joined the club the Soos sat in fifth place. A late-season hot streak, however, pushed the club into the playoffs. In the Western League title series, Sioux City lost the first two games to Lincoln. In game three, it was Henley who swung the momentum. He doubled and later tripled to help the Soos to a 6-4 win. The next night Henley socked two triples and drove in a run with a sacrifice fly to highlight an 11-10 Sioux City victory. The Soos won the next two games to claim the pennant. In 64 games with the club Henley hit .295 and belted 7 home runs. At a hotel celebration after the title winner, Becker sidled up to his young rookie. With a drink in hand he said, “I think you’ve got a chance to be a good ballplayer, but I still don’t like you.”

Henley’s first professional spring training was spent with the New York Giants, where his skills and hustle caught the eye of Leo Durocher. Henley so impressed his boss that the Giants skipper weighed taking the right-field job away from veteran Willard Marshall in favor of the 20-year-old rookie. When sportswriters asked if Henley would make the ballclub, Leo barked, “Absolutely! You can count on it.”2 Joe King of the New York World Telegram wrote that Henley was “the phenom who did everything asked of him, and who was nominated to run Marshall off the field.”3

During the final days of spring training, Giants owner Horace Stoneham flew to New Orleans, where his ballclub was playing an exhibition game. Notoriously loyal to veterans to a fault, Stoneham overruled Durocher’s wishes. A tearful Gail Henley was pared from the roster.

Solid minor-league seasons in 1949, ’50, and ’51, in which he twice hit over .300, brought Henley back onto the Giants’ radar in the spring of 1952. This time the team was facing a looming crisis. Its star center fielder, Willie Mays, had been drafted into the Army. He was scheduled to leave for induction in May and would be away for two years. Leo Durocher fretted over whom to play in Mays’s absence. Henley made a strong case for the job during spring training. Among his highlights were a four-hit exhibition game against the Chicago Cubs and a double coming off the bench against Cleveland. When New York sportswriters pinned the nickname “The Blond Belter” on Henley, it gave every indication that he was about to make the team. Durocher boldly proclaimed, “Henley might be the guy. I’ve always liked what I’ve seen of him.”4 As the Giants wrapped up spring training with a series of exhibition games in the South, Henley got considerable playing time. He subbed in right field and started a few games in center. When spring training concluded, the rookie had made the big-league club and headed north for opening day.

The aura and excitement of a rookie’s first Opening Day was drowned for Gail Henley by bad weather. Rain washed out the season opener with Philadelphia. As the players changed out of their uniforms, Leo Durocher summoned Henley to the manager’s office. He had been pondering options for a center-field replacement and felt Henley would be better prepared for the task with regular at-bats in the minor leagues rather than sitting on the bench in New York. “We’d like you to go out and play center field,” Durocher explained. “You can pick any farm club you want, and we’ll bring you back once Willie is going to leave.”

The choice came down to Minneapolis or Tulsa. Henley was wary of going to Minneapolis. Bad blood existed between Dutch Ruether, the scout who had signed the young outfielder, and Minneapolis general manager Rosy Ryan. Ruether warned that Ryan might take it out on Henley. The Giants’ prospect decided to go instead to Tulsa.

While the skies cleared 24 hours later, the results dampened Henley’s prospects with Durocher’s Giants. New York had made a deal to get Bob Elliott from Milwaukee. As Henley was heading for Tulsa, Elliott hit two home runs against the Phillies, and just like that Durocher’s ideas for center field changed.

After a sluggish start to the season, Henley went on a hitting tear with Tulsa. By May 19 he had built a 15-game hitting streak. His .301 batting average put him among the league leaders. Eight days later, however, when Mays left the Giants and was inducted into the Army, Henley was not recalled as promised. The Giants decided to go with a center-field rotation of Bob Elliott, Bobby Thomson, and Hank Thompson instead.5

Despite the disappointment, Henley forged on. In August he built another impressive streak, hitting safely in 16 consecutive games before a collision with the outfield fence left him with a shoulder injury. Henley’s injury had an unintended consequence. It made him a better hitter. “Back then, you played,” he reminisced. “I could barely lift my arm. When I had to throw, I was practically throwing underhand.” Henley endured intense pain when he swung a bat and altered his swing to compensate. The change saw him consistently hit the ball to the opposite field. “I’d been a dead pull hitter to that point,” he said. He adopted the hitting style and flourished.

The Giants’ prospect turned heads with his fielding as well. Henley set a league record with 27 outfield assists. “John Tabor was the groundskeeper there, and he kept that field like a pool table,” Henley said by way of explanation. While the Giants ignored his performance, the prospect’s play did gain the attention of one of baseball’s best talent evaluators. It would not be long before Branch Rickey would act on it.

For several months during the 1952 season, the Cincinnati Reds had been trying to pry Gus Bell from the Pittsburgh Pirates. Every inquiry was met with a hasty “no” from the Pirates’ general manager, Branch Rickey.6 When the Reds learned that Rickey was fond of Henley, they asked if he would trade Bell for a package of players that included the former USC standout. Rickey jumped at the chance.7 On October 13 Cincinnati swapped Frank Hiller to the Giants for Henley. The next day they traded Henley, Cal Abrams, and Joe Rossi to Pittsburgh for Bell. “I got a letter from Rickey’s scout, Clyde Sukeforth,” Henley remembered. “He said I was the primary player in the trade.” Looking back on the swap six decades later, Henley called it “Rickey’s worst trade.”

Henley’s first spring training with the Pirates was spent in Havana, where Rickey had persuaded the country’s tourism board to cover his team’s expenses. The team was housed at the Club Marianau, where players roomed four to a bungalow. “Breakfast, well the eggs were something else. The milk was powdered milk. It tasted like chalk. I ended up eating crackers and peanut butter with water for breakfast. The best meal was after the game. We played every day, and afterwards we’d get fresh milk and fresh fruit. It was very refreshing.”

Circumstances beyond his control meant Cuba would be the only time that Henley played with the big-league Pirates in 1953. Pittsburgh’s roster was saddled with three bonus players who had to be kept. Rickey had also appeased angry minor-league club owners with the promise that he would not promote prospects from the New Orleans or Hollywood clubs.8 This left Henley with the Pirates Double-A team, New Orleans, playing for Danny Murtaugh. “My favorite manager. He was great to play for.” Henley enjoyed an all-star season with the Pelicans. He threw out two runners at the plate in a May game with Birmingham, then later won that game with a 10th-inning triple. He blasted two home runs and drove in six runs in a July game with Branch Rickey watching. Henley was the second leading vote-getter among outfielders for the league all-star game. His energy and tenacity were felt in a game with Chattanooga, when a hard collision at home plate left the Lookouts’ catcher with a broken collarbone. Henley hit .290 with 82 runs batted in and 12 home runs. It did nothing but brighten Rickey’s enthusiasm and provided the final bit of seasoning Henley needed to succeed in the big leagues.

Twenty-three rookies made major-league debuts on Opening Day of the 1954 season. One of them was Gail Henley. In his first at-bat in the big leagues, Henley pinch-hit in the bottom of the sixth inning and grounded out to shortstop against Philadelphia. In each of the Pirates’ first five games, Fred Haney used his talented Californian in a pinch-hitting or defensive-replacement role. On Monday night, April 19, at the Polo Grounds against his former team, the New York Giants, Henley started in right field. In the top of the first inning the 22-year-old got his first big-league hit, a two-run home run off the Giants’ Jim Hearn.

Haney kept Henley in the starting nine, and he hit safely in each of the next four games. Against Brooklyn on April 25, Henley smashed a first-inning line-drive single to right field that chased Don Newcombe from the game. Two innings later he doubled to left field. In the top of the sixth inning came a play that would alter the course of Henley’s career.

With one out, Carl Furillo represented the go-ahead run on second base for the Dodgers. George Shuba came to the plate. “I moved in a step or two,” Henley recalled. Shuba shot a ball to deep right-center field, and Henley turned in hot pursuit. He extended his arm just as the ball caromed off the brick wall. A split-second later, Henley, running full speed, slammed face-first into a recessed edge of the outfield wall. The violent force of the collision sent him flying onto his back and to the ground. Frank Thomas raced over from center field. He saw blood spurting from Henley’s face “like a geyser.” Henley struggled in and out of consciousness. He tried to get to his feet to track down the ball. Thomas planted a spiked shoe firmly on his teammate’s chest and barked, “Stay down!”9

Henley was helped into the Pirates clubhouse. “Dr. Feingold stitched me up,” he recalled. “Doc Jorgensen, the trainer, was nervous from all the blood. He couldn’t handle the scissors to help Dr. Feingold, so they had one of the coaches, Ed Levy, assist.” It took 10 stitches to close two large gashes, one above his left eye and the other on his nose. He also had a separated wrist.

The next day was an offday. Players, coaches, Haney, and Rickey were slated to take part in the annual Grandstand Mangers Club Luncheon at the Hotel William Penn. Photographers clicked away as Branch Rickey inspected Henley’s heavily bandaged eye and nose. From the dais Rickey praised his young outfielder. “This boy went pell-mell into the wall, not thinking of an injury. It shows the desire of the club. I understand he commented while lying on the ground that he should have made the catch. I’m happy about that.”10

The following day the Pirates embarked on a four-city road trip. Henley stayed behind, which left the team shorthanded. While convalescing, the Pirates outfielder made a fateful nightclub sojourn with a teammate one night. Henley joined Cal Abrams to get out and kick up his heels. “A little Arthur Murray two-stepping,” he laughed. Word somehow got back to Rickey, who was incensed. “Rickey had spies everywhere,” Henley said. “I’m sure Branch got the message a couple of his players were hanging out dancing while the team was out of town. Heck, I wasn’t hard to miss with the big bandage on my eye.”

After being out for 10 days, Henley rejoined the Pirates in Milwaukee for the last two games of the road trip. Haney called upon Henley to pinch-hit for Bob Purkey, and he shot a line-drive single up the middle off Gene Conley to push his batting average to .310. The next night he pinch-hit for George O’Donnell. As he ran toward first base on a groundout to the second baseman, Gail Henley had no idea it would be the last time he would play in a major-league game.

When the Pirates returned home, Henley got a phone call at his apartment from Fred Haney. “We’re sending you to New Orleans. You are to leave right away.” Henley was angry. He demanded to speak to Rickey, but Haney pointed out that it was a Sunday and that Rickey refused to do business on the Sabbath.

The next day one of the Pittsburgh newspapers trumpeted the move as HENLEY FORCED TO WALK THE PLANK. “There’s a saying in baseball. When you’re called up, it takes you six hours to get there. When you’re optioned, it takes you six days,” Henley laughed. It was a saying he lived. Together with Bill Hall, who had also been optioned to New Orleans, the pair drove from Pittsburgh in Henley’s Oldsmobile and took their time doing so. When they arrived in the Crescent City, they found that the team had already left on a road trip. Henley and Hall hurried to the airport and caught a flight to join the Pelicans in Nashville. “When I came out on the field to warm up, I looked up in the stands and there was Branch Rickey,” Henley said. “His arms were crossed and I’d never seen his face so red. He was really pissed off. I just kept walking to the outfield. We never spoke again.”

The incidents left Henley mired deep in Rickey’s doghouse. At the end of the season he was removed from the Pirates’ 40-man roster and not invited to spring training with the major-league club. Henley’s standing with Rickey sent the outfielder’s career on an unexpected journey.

The 1955 season brought one of Rickey’s pet projects to fruition when the Mexican League was made a part of the minor-league system. The Pirates quickly aligned with the Mexico City Tigers to make the club their Double-A farm team. Rickey badly underestimated the level of talent in the Mexican League, however, and the Tigers got off to a terrible start. Their manager, George Genovese, pleaded for help. Rickey offered a list of players that the Pirates were considering for release. Henley was one of four players the manager eagerly asked for. “The club was 5-18 when I got there, and there was talk that George’s job was on the line,” Henley remembered. In his first game with the Tigers, Henley stepped to the plate in the top of the eighth inning with the game tied 5-5 and promptly belted a home run. The triumph started a 14-game win streak.

A long Henley home run on July 3 pushed the Tigers into second place. The tenacity that the hustling Californian brought to the diamond each night almost sparked a riot during a testy game in Veracruz. The opposing shortstop had twice tried to trip Henley on the basepaths. Back in his team’s dugout the angry outfielder told his Spanish-speaking manager to warn the player that if he did it again, “I’m going to nail his ass!” Three innings later with Henley on first base, a groundball was hit to the Veracruz second baseman. When the shortstop came to the bag to take the throw, Henley took him out hard. As the player writhed on the ground, injured and in pain, fans who were angry with Henley showered the field with debris. They screamed insults and made threats. “Grab a bat,” Genovese shouted to his players in anticipation of a confrontation when the game ended. Henley dove into a waiting taxi and hurried out of the ballpark before trouble could start.

In early August with the team in the thick of a pennant race, a crisis struck. The Tigers entered a game with Veracruz with just one catcher. When the lone catcher argued the umpire’s call after the first pitch of the game, he was ejected. Genovese flew into a rage. As the manager railed, Henley raced in from center field. “Skip, Skip,” he cried out, “I can catch! I can catch!” The words instantly brightened the manager’s mood. “I was all-CIF in high school,” Henley explained while he strapped on the gear. He quickly reacquainted himself with the position and went on to team with Jaime Ochoa, the Tigers pitcher, on a no-hitter.

By mid-August Henley was embroiled in a fierce fight for the Mexican League batting title. On the final day of the season, the Tigers won the pennant, while Henley finished third in the batting race, a mere .00004 out of second and .002 behind the leader. “Two more days and I’d have won the damn thing,” he would laugh.

Throughout the season Genovese heaped praise on Henley in every conversation he had with Branch Rickey. “He plays hard for me,” the manager gushed. “He can help you there in Pittsburgh.” Nothing that Genovese said, however, would change Rickey’s position. Henley was in an inescapable doghouse.

Henley spent two more seasons in the Pirates’ farm system before he was sold to Detroit. He played three seasons with the Tigers’ Double-A farm club at Birmingham before the team’s general manager, Eddie Glennon, approached him one day with an idea. “How’d you like to manage,” he asked. Henley jumped at the chance. In 1961, at the age of 31, Gail Henley hung up the bat and glove to begin a new career. For six seasons he managed in the Tigers’ farm system before stepping away from the game to enter the business world. While working in the uniform-supply industry, Henley was asked to coach a team of 14- and 15-year-olds in Temple City, California. It was a challenge he readily took on. After one of his team’s games, the mother of one of the players introduced herself. She was Marge Roundtree, the secretary to the Los Angeles Dodgers’ scouting director, Al Campanis. “You should talk to Al,” the woman suggested. Kenny Meyers, a longtime Dodgers scout, was leaving to join the California Angels. Campanis was looking for a replacement. Henley took copies of reports he had written while managing in the Tigers organization. “Looks like you know what you’re doing,” Campanis remarked. A few days later Campanis called. “We’ve got a job for you,” and with that, Henley was back in professional baseball.

For the next 26 years Henley scouted for the Dodgers. He began by covering a section of Southern California, then saw his territory expand to include Central California and then southern Nevada and Arizona. His responsibilities grew. Over six seasons, once the draft had been executed, the Dodgers asked Henley to manage their short-season rookie-league club. Ultimately he became a cross-checker. In 1994 cuts came to the Dodgers’ scouting department. Seeing the writing on the wall, Gail Henley elected to retire, ending a career in professional baseball that had spanned 62 seasons.

People who were close to Henley during his playing days and saw his talent and the determination he played with found it hard to believe that another chance to play in the big leagues never came his way. “I don’t think it was attitude,” Henley reflected, “because when I crossed the white lines, I played the game like there was no tomorrow. I was very fortunate to be around outstanding people. Their ideas helped me along the way. Any lack of success on my part, however, was my fault.” He hit safely in 9 of his 14 games and batted .300 but said, “I don’t think they ever really saw what talent I had.”

Gail and his wife, Barbara (they were married in 1956), had two sons, William and Daniel, and a daughter, Patricia. William, an outfielder, played one season (1980) in the San Diego Padres farm system. Daniel, an infielder, was the captain of the last University of Southern California team coached by Rod Dedeaux, and was a teammate of Randy Johnson, Jack DelRio, and Mark McGwire. A seventh-round draft choice of the Los Angeles Dodgers in 1986, Daniel spent six seasons in the minors, five in the Dodgers farm system and one with the Chicago White Sox organization. He played at the Triple-A level three of his six seasons.

As of 2016 Gail and Barbara Henley resided in La Verne, California, about 30 miles east of Los Angeles.

Last revised: November 11, 2016

Acknowledgments

The writer gratefully thanks Gail Henley for his time, information, and friendship.

Notes

1 Much of this biography is based on the author’s conversations with Henley between 2009 and 2016 as well as conversations with George Genovese from 2009 to 2015.

2 The Sporting News, April 20, 1949.

3 Ibid.

4 The Sporting News, October 22, 1952.

5 The Sporting News, June 4, 1952.

6 The Sporting News, October 29, 1952.

7 Ibid.

8 Andrew O’Toole, Branch Rickey in Pittsburgh (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2000).

9 Conversation with Frank Thomas.

10 The Sporting News, May 5, 1954.

Full Name

Gail Curtice Henley

Born

October 15, 1928 at Wichita, KS (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.