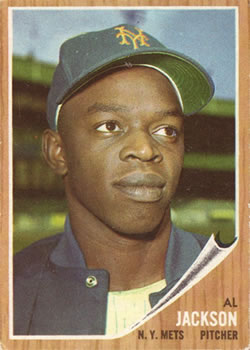

Al Jackson

In George Vecsey’s modestly titled Joy In Mudville: Being a Complete Account of the Unparalleled History of the New York Mets from Their Most Perturbed Beginnings to ’Their Amazing Rise to Glory And Renown, a moment illustrating the time-flies transformation of the Mets franchise from bottom feeders to top dogs in eight short seasons is captured as poignantly as it transpired.

The episode occurred in the jubilant Mets clubhouse on September 24, 1969, in the minutes after the Miracle Mets clinched their first positive title of any kind, the National League Eastern Division championship. Into the champagne-soaked celebratory scrum walked Original Met Hot Rod Kanehl. Kanehl was an icon of the 1962 Mets, a scrappy utility-playing avatar of those most perturbed beginnings—he legendarily accepted manager Casey Stengel’s offer of $50 to get himself hit by a pitch with the bases loaded—and, having involuntarily retired from the majors in 1964, ventured into the clubhouse as no more than a suitably dazzled and slightly grizzled spectator of the team’s amazing rise to glory.

Kanehl, 35, visiting the party alongside fellow long-gone Original Met Craig Anderson, then 31, sought out center fielder Tommie Agee, 27, and introduced himself. After Hot Rod moved on, Agee, according to Vecsey, turned to a friend and asked, “Who is that?”1

Hot Rod Kanehl was a stranger in a strange land that Wednesday night, underscoring the incongruity of an Original Met wandering among the Miracle Mets. Vecsey’s anecdote showed how far the Mets had traveled to shed their family resemblances and how little they were tangibly related to the foibles and foundering of their very first forebears, even if the Original Mets presaged the Miracle Mets by a mere seven years.

All of which makes the presence of a vintage April 1962 New York Met among those who would become October 1969 world champion New York Mets—not as a well-wisher but as a peer—somewhat startling. If you scour the complete roster of those ’69 Mets, one name jumps out as amazin’ly anachronistic: Al Jackson.

It’s not that Jackson was chronologically, even for the era, out of code. The diminutive southpaw reliever—forever “Little Al Jackson” to Mets announcer Bob Murphy—was 33 during the 1969 baseball season. Hoyt Wilhelm, albeit with the aid of a knuckleball, helped pitch the Atlanta Braves toward the same inaugural National League Championship Series as the Mets at age 47. Bob Gibson was born not seven weeks earlier than Jackson and won 20 games for the fourth-place St. Louis Cardinals. Even in an era when management was hesitant to trust the skills of anyone over 30, Jackson’s left arm was not hopelessly dated. But it and he were something out of another age for the 1969 Mets. He was, within the context of the youth and emerging success of that club, in the right place at the wrong time.

It was not an unfamiliar circumstance for Jackson, a man with an uncanny knack for being on teams that reached October around him but never with him square in the middle of the hoopla. He appeared as a Pittsburgh Pirate in 1959 and 1961, but managed to miss 1960, the year of Bill Mazeroski’s World Series heroics. He was in Cincinnati as the gears of the Big Red Machine were tightened for the dynasty that lay ahead but was released one week into Cincy’s 1970 pennant romp. He was a part of the 1967 world champion Cardinals, going 9-4 starting and relieving, but of the 10 pitchers—including four lefties—skipper Red Schoendienst chose to shut down the Boston Red Sox in seven games, none of them was named Al Jackson.

So it was that the 1969 Mets, remembered for pitchers like Tom Seaver, Jerry Koosman, Nolan Ryan, and Tug McGraw, rendered Al Jackson’s participation in baseball’s miracle of miracles into a footnote. The Mets, needing to clear roster space (Ryan was coming off the disabled list as second baseman Ken Boswell returned from military-reserve duty), sold Jackson to the Reds on June 13. The deal severed the last active link the Mets had to their most humble beginnings, but only for the time being. Four seasons later, the club would reacquire Jackson’s 1962 teammate, Bob L. Miller, to help out in the midst of their comparably unlikely 1973 pennant run. Miller’s final relief appearance, on September 28, 1974, wound up marking the last time an Original Met played as a Met. (Though Ed Kranepool was a ’69 Met—and would stay with the team for another decade—he was a late arriver to the ’62 team, receiving a few token at-bats at the Polo Grounds after being signed out of high school earlier in the year.)

Whatever sentimentality might have lingered over the transaction was ultimately obscured by Jackson’s undistinguished 1969 Mets line: no decisions; 13 earned runs allowed over 11 innings; the team’s record a most unmiraculous 1-8 when Al Jackson took the mound.

Jackson’s final outing as a 1969 Met, on May 22, was straight out of 1962: with the Braves up, 10-0, he replaced Cal Koonce in the bottom of the seventh at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium. With a runner on first when he entered, Jackson surrendered a single, a walk, a sacrifice fly, a fielder’s choice, an RBI single, and a two-run double. When he gave way to Ron Taylor, the Mets trailed, 14-0. The loss lowered the Mets’ record to 18-19, noteworthy in Mets lore because it dropped the Mets below .500 one night after the players claimed to disbelieving reporters that they didn’t consider a break-even mark any kind of milestone, that they had loftier goals in their immediate sights.

The Mets would sag to 18-23 before forever burying the ghosts of 1962 by reeling off 11 consecutive wins. But by then, Al Jackson—1969 ERA of 10.64—was all but bound for Ohio, relegated to the role of observer of a miracle as much as Kanehl and Anderson and any Original Met. (His wallet missed the action as well; by completing ’69 as a third-place Red in the N.L. West, Jackson earned an also-ran World Series share of $203.97, while a full winner’s share with the Mets was worth $18,338.18.)2

The thickest of ironies here is Al Jackson, one of the least consequential Mets of 1969, was perhaps the 1962 Met who soared the highest above his team’s sorry morass. Granted, no individual on a team that accumulated 120 losses could be said to stand completely apart from the muck of historic futility, but Jackson, despite his surroundings, showed honest promise and progress to the fans who populated the Polo Grounds at its end and Shea Stadium at its beginnings.

A cross-section of Jackson’s early Met staff-mates admired his talent and tenacity. Fellow pitcher Clem Labine told Bill Ryczek, in his 2008 book, The Amazin’ Mets: 1962-1969, that Jackson “had the best stuff” of any of the Originals. “He knew what he was doing,” Galen Cisco testified. Put him on a club that could hit, Gary Kroll suggested, and “he’d win 20 games every year.”3

A native of Waco, Texas, born on December 26, 1935 as the lucky 13th of 13 children, Alvin Neill Jackson attended Wiley College in Marshall, Texas, prior to signing with Pittsburgh in 1955. He led the Western League in 1958 with a 2.07 ERA while winning 18 and logging 230 innings in Lincoln, Nebraska, and followed that with a 15-4 season in Columbus. In that 1959 season he also got in eight games and 18 innings with the Pirates. Yet the Bucs bypassed him in their championship year of ’60 and (after only three appearances in ’61) exposed him to the National League expansion draft. Jackson was chosen by the Mets as one of its $75,000 choices and started the third game ever in the franchise’s existence.

It was a loss.

Al Jackson was not alone among Mets pitchers in defeat. The 1962 Mets lost their first nine games, but Jackson would do what he could to turn things around, no matter how much like spitting into the ocean those efforts amounted to. He notched the club’s first shutout, in the opener of a doubleheader against Philadelphia on April 29, thereby forging the Mets’ first-ever winning streak (it pushed them to 3-12). His second shutout, over fellow NL newcomers the Houston Colt .45s, represented the Mets’ first-ever one-hitter, the only Colt safety coming off the bat of Joey Amalfitano in the first (he came within five outs of a no-no at Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field on July 21, 1965, seeing it broken up by Willie Stargell in the eighth and settling for a two-hit, 1-0 win). On those 40-120 freshman Mets, Al Jackson threw a team-leading four shutouts—their only four shutouts in ’62. All of them, strangely enough, were pitched in the first games of doubleheaders. It was enough to earn him recognition on the Topps 1962 All-Rookie team.

Al Jackson was not alone among Mets pitchers in defeat. The 1962 Mets lost their first nine games, but Jackson would do what he could to turn things around, no matter how much like spitting into the ocean those efforts amounted to. He notched the club’s first shutout, in the opener of a doubleheader against Philadelphia on April 29, thereby forging the Mets’ first-ever winning streak (it pushed them to 3-12). His second shutout, over fellow NL newcomers the Houston Colt .45s, represented the Mets’ first-ever one-hitter, the only Colt safety coming off the bat of Joey Amalfitano in the first (he came within five outs of a no-no at Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field on July 21, 1965, seeing it broken up by Willie Stargell in the eighth and settling for a two-hit, 1-0 win). On those 40-120 freshman Mets, Al Jackson threw a team-leading four shutouts—their only four shutouts in ’62. All of them, strangely enough, were pitched in the first games of doubleheaders. It was enough to earn him recognition on the Topps 1962 All-Rookie team.

Nevertheless, the most famous game those ’62 Mets played, also a twin bill opener, may tell Al Jackson’s story of being a bit of a bystander to history. It was Sunday, June 17, 1962, Father’s Day against the Cubs at the Polo Grounds. Jackson started and fell behind, 4-0, immediately in a top of the first that was capped by Lou Brock’s two-run homer into the distant center-field bleachers and set up when first baseman Marv Throneberry didn’t execute a rundown. His teammates, in a rare display of timely support for one of its pitchers, came to his rescue… in their unique way.

With one run in and two runners on, Throneberry hit what everybody at the Polo Grounds assumed was a triple. Except “Marvelous Marv” neglected to touch various combinations of first and second bases. Though the two runners scored, Throneberry was ruled out on appeal. Jimmy Breslin in Can’t Anybody Here Play This Game? chiseled what happened next into Mets mythology, reporting that after Charlie Neal homered, Stengel bolted from the dugout to point to each base to make sure every bag was touched.

Little remarked upon in that comedy of errors that exemplified the 1962 Mets was that Al Jackson acquitted himself pretty well the rest of the day, pitching into the ninth and giving up only an Ernie Banks home run in the third and a Brock RBI double in the eighth, and allowing the Mets a chance to come back on the Cubs. (Naturally for Jackson and those beleaguered Mets, Throneberry struck out as the potential winning run with two out in the bottom of the ninth; they lost the nightcap by a run as well.)

With outings like those too often the norm—a norm that included a 3-1 complete-game loss to the Phillies on August 14 in which the lefty went 15 innings, still the longest a Met starter has gone in service to a decision, to absorb his 15th defeat—and a final record that reflected that reality at 8-20 (not even the most losses among Mets starters; Roger Craig suffered 24 L’s), it is little wonder Jackson uttered and Breslin inimitably scribbled the southpaw’s assessment of the 1962 Mets after a particularly frustrating defeat: “Everybody here crazy”4

Seriously speaking, Jackson shone as the best of a fey lot on those first Mets staffs. Nobody struck out more hitters in the Mets’ first four grisly campaigns; nobody posted more victories in a single season than the 13 he put up in ’63 for a 51-111 outfit; he earned Opening Day starts in ’64 and ’65; and the 10 shutouts he spun between 1962 and 1965 are still good for sixth all-time (tied with Ron Darling) on the all-time Mets career list. Al Jackson trails only Seaver, Koosman, Jon Matlack, Dwight Gooden, and David Cone in that category. He remains fifth among Mets pitchers in complete games with 41, behind only Seaver, Koosman, Gooden, and Matlack.

It’s little wonder that as the Mets moved into Shea Stadium in 1964, Little Al Jackson stood tallest on a roster that was otherwise easily overlooked. The Sporting News hailed him as the likeliest candidate to become “Shea Stadium’s first 20-game winner,”5 a proposition that seemed that much more realistic on April 19 when Jackson’s 6-0 whitewashing of the Pirates went down as the club’s first win in their new home. “I thought it was heaven,” Jackson said of Shea Stadium in Newsday in 2008, particularly in comparison to the doomed Polo Grounds.6

It was the left-hander’s final start of 1964, however, that remains his signature Mets moment. With the Cardinals trying to take advantage of the Phillies’ epic collapse, St. Louis saw the NL flag as theirs for the taking by dint of the schedule maker’s kindness: the Redbirds’ final three games came at home against the 51-108 Mets. . . and they had ace Bob Gibson going against the perennial cellar dwellers.

But the Mets had Al Jackson going against the first-place Cardinals and on Friday, October 2, Jackson got the best of Gibson, beating the future Hall of Famer, 1-0, when he scattered five hits and clinched the best-ever win total by the franchise to date. One might also argue that beating a team like St. Louis in such a situation might have been the franchise’s best-ever win to date, but that point is moot because the next day they beat the Cardinals again. The Cards, with Gibson coming out of the bullpen on one day’s rest, righted the ship on Sunday by coming from behind to finally defeat the Mets and win their first pennant since 1946.

In 2008, Jackson recalled for Newsday the Cardinals’ reception for him as he walked through their clubhouse on that last Friday night to appear on Harry Caray’s postgame show. “Oh, did they call me a bunch of names. They said, ‘You guys are 59 games out of first place and you’ve got to pitch a game like this?’ Man, did they rip me.”7

The 10th-place Mets actually trailed the first place Cardinals by only 41 games entering play on October 2, but the stakes were too high for statistical niceties in St. Louis.

That was as close as Al Jackson ever came to a pennant race as a New York Met. One year and one day after making the Cardinals sweat, Jackson completed his first term in Flushing. Though the prescient might have seen the seeds of a miraculous future—the home team lineup on October 3, 1965 included 1969 mainstays Ron Swoboda, Bud Harrelson, and Ed Kranepool—to Jackson, it had to look like the same old same old. He lost the first game of a season-ending doubleheader to the Phillies, 3-1, leaving his bottom line for ’65 at 8-20. . . identical to the 8-20 of ’62. His respective ERAs (4.40 in ‘62, 4.34 in ‘65) were eerily similar, too, while the team’s record of 50-112 was their worst since their first. Jackson remains the only Met to ever lose 20 games in a season more than once, but he was certainly not alone in piling up the L’s; in both ’62 and ’65 Jackson wasn’t even the team leader in that category (Roger Craig and Jack Fisher, respectively, each lost 24).

Losing ballgames by the bundle hardly represented the highest hurdle Jackson had to overcome. Growing up African-American in Waco when he did made him realize he wasn’t experiencing an idyllic childhood amid a segregated society. “We lived in a small world, a separate world,” he told Steve Jacobson in the 2007 book, Carrying Jackie’s Torch: The Players Who Integrated Baseball— and America. “We did have a black community you could kind of dwell in. You knew when you were crossing the tracks and where you stayed. You didn’t go to white restaurants, because I tried that and it didn’t work. Looking back makes me angry.”8

Jackson would encounter discrimination throughout his minor league climb and have to put up with the stubborn institutionalized remnants of it in 1962 during the Mets’ first spring in St. Petersburg, Florida, where the team’s headquarters hotel, the Colonial Inn, grudgingly allowed African-American players to stay in its rooms, but not to swim in its pool, eat in its restaurant, or drink in its bar.

More than 40 years later, Jackson recalled his reaction to how he and his African-American teammates were treated: “I thought, I’ll be damned.”9

In the 1965 offseason, Jackson was granted a professional reprieve from the steady Metropolitan drumbeat of losing when he was traded with Charley Smith to the Cardinals for former NL MVP Ken Boyer. None other than Stan Musial, at the time a Redbird executive, praised Jackson to United Press International as “a good competitor” who “can beat the tough clubs.”10 Come 1967, Jackson was part of a team that glided to a National League championship but, despite going 9-4 as a spot starter, he wasn’t considered enough of an essential ingredient by the Cards to be used in the World Series or retained for their repeat run in ’68. The Sporting News lumped him in among the “dead wood” St. Louis cleared away after winning the fall classic without him.11

Jackson returned to the Mets as player-to-be-named payment for reliever Jack Lamabe the day after the ’67 Series ended; the native Texan told Cardinal history blog RetroSimba in 2012 that he was aware he’d be part of the deal well before his involvement was announced, but “the Mets told the Cardinals they could keep me until the end of the season.”12 Though fellow Original Met Gil Hodges was back in New York to manage the 1968 club, the Polo Grounds reunion in Queens didn’t result in a renaissance for Jackson, who pitched only 25 times (nine starts) for his old teammate and new skipper. His appearance in the Opening Day slugfest against the brand-new Montreal Expos on April 8, 1969, wherein he surrendered an immediate home run to Rusty Staub and allowed two more baserunners who would score, did not augur well for Jackson’s longevity in his encore Mets tenure.

A little more than two weeks after Jackson’s June sale to the Reds, Tom Seaver (en route to becoming Shea Stadium’s first 20-game winner) won the 44th game of his young career and, in doing so, broke Little Al’s franchise mark for most wins. Their Mets circumstances couldn’t have been more different. After beating Pittsburgh on June 29, Seaver’s lifetime mark was 44-28 and his club was in second place, seven games over .500. Al Jackson’s body of yeoman work as a New York Met netted him no better than a record of 43-80, providing the bulk of his career 67-99 won-loss ledger—a very respectable 24-19 when not a Met.

When he was a Met between 1962 and 1965, Al Jackson’s team’s winning percentage was .300. Even Tom Seaver would have had a tough time being terrific with the odds stacked so solidly against him. Seaver eventually took away Jackson’s club loss record as well, though it took him until 1974. (Jerry Koosman holds the record for Mets losses with 137.)

After retiring as a player, Jackson served as pitching coach with the Red Sox (1977-79) and Orioles (1989-91) but otherwise instructed Mets pitchers on an ongoing basis for decades until suffering a stroke in May of 2015. Jackson, who would eventually settle in the Mets’ current spring training home of Port St. Lucie, Florida, did try his hand at managing with Rookie league Kingsport in 1981 (21-49), but found he served the organization best over the long run by working exclusively with pitchers.

“No one,” the Mets’ 2018 media guide declared, “exemplifies the Mets organization more than Al Jackson.”13 The internal reverence for their stalwart southpaw might have been best reflected in the fact that not only was he invited back for the Shea Goodbye ceremonies of 2008, but also the 40th-anniversary celebration of the 1969 Mets at Citi Field in 2009. The latter is noteworthy because no other player who wasn’t around the World Champions during their miraculous postseason was part of those commemorative festivities. (Jackson entered the field in 2008 in a Mets jersey bearing his initial number of 15 but returned in 2009 wearing No. 38, what he wore before he was released in ’69.)

Upon news of the stroke that hospitalized Jackson at age 79, longtime Mets beat reporter Marty Noble, then with MLB.com, called the organization’s exemplar of longevity “as good a man as you could hope to meet in a half-century around the game. By the pitching standards baseball holds so dear, he produced a mostly modest career. But his character, happy demeanor and unsurpassed decency have put him in the pantheon of the exalted and splendid folks who have walked the planet.”14 The concept of Jackson being part of the Mets family never seemed more literal than when one of the two sons he raised with his wife Nadine, Reggie, pitched for three of the Mets’ minor-league affiliates between 1982 and 1984.

Ron Darling credited Jackson, then pitching coach under Davey Johnson at Triple-A Tidewater, with staying on him relentlessly in 1982 and designing special workouts to prepare the 22-year-old pitcher to make the final step to the major leagues. “I was young and single, living on the beach in Norfolk, Virginia. I was content,” Darling wrote in The Complete Game. “But Al kept on me. He’d say, ‘What do you have to be content about? You haven’t done anything. You haven’t struggled.”’15

Darling said of Jackson’s pitching philosophy, “According to Al, starting the game is a process, but once the game begins there’s no easing into it. It’s full-on, right from the first pitch.”16

Jackson was the bullpen coach for the 1999 Wild Card and 2000 National League champion Mets under Bobby Valentine. Those squads’ left-handed ace, Al Leiter, credited Jackson for lifting his game, an echo, perhaps, of the advice Jackson told Newsday he gave young Seaver and Koosman in 1968 and ’69 when he was a Mets’ elder statesman and they were the league’s unmatched young guns. A self-described “lifer,” Jackson’s wisdom literally reached far and wide during the latter stages of his tenure as a pitching consultant. In 2007, he was part of a delegation of Major League Baseball officials who traveled to West Africa to teach and promote America’s National Pastime and, presumably, answer lingering questions regarding the day Marvelous Marv Throneberry didn’t touch second.

Or first.

Yet few around the game would dispute that as a pitcher, a mentor and a person, “Little Al” covered all the bases where it counted. Mets fans have crowded his “memories” page on Ultimate Mets Database with loving recollections of his career and their experiences meeting him. “As long as I’ve known him,” Jacobson added in Carrying Jackie’s Torch, “Al Jackson has been an infinitely cheerful man, and that goes back to the time of the Original Mets in 1962.”17 Al Jackson died on August 19, 2019 at the age of 83.

SOURCES

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted Baseball-Reference.com, UltimateMets.com, and Goldaper, Sam. “Sports People: Reggie Who?” New York Times, June 14, 1982.

NOTES

1 George Vecsey, Joy in Mudville: Being a Complete Account of the Unparalleled History of the New York Mets from Their Most Perturbed Beginnings to Their Amazing Rise to Glory and Renown (New York: The McCall Publishing Company, 1970), 217.

2 “Pennant Playoffs Sweetened World Series Pot,” The Sporting News, November 29, 1969.

3 Bill Ryczek, The Amazing Mets: 1962-1969 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2008), 18-19.

4 Jimmy Breslin, Can’t Anybody Here Play This Game? (New York: Avon, 1963), 92.

5 Barney Kremenko, “Lefty Jackson No. 1 Pearl in Met Oyster,” The Sporting News, May 2, 1964.

6 Mark Herrmann, “Al Jackson Knows How Bad the Mets Can Be,” Newsday, June 29, 2008.

7 Herrmann.

8 Steve Jacobson, Carrying Jackie’s Torch: The Players Who Integrated Baseball—and America (Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books, 2007), chapter 8 (Kindle edition).

9 Jacobson, chapter 8.

10 Mark Tomasik, “Why Cardinals Traded Ken Boyer to Mets.” RetroSimba.com, October 20, 2015. https://retrosimba.com/2015/10/20/why-cardinals-traded-ken-boyer-to-mets/

11 Neal Russo, “Cards Chop Dead Wood; Protect 2 Young Sluggers,” The Sporting News, November 4, 1967.

12 Mark Tomasik, “An Interview with former Cardinals pitcher Al Jackson.” RetroSimba.com, January 16, 2012. https://retrosimba.com/2012/01/16/an-interview-with-former-cardinals-pitcher-al-jackson/

13 New York Mets Media Guide: 2018, 216.

14 Marty Noble, “Here’s to a Speedy Recovery for Al Jackson,” mlb.com, May 8, 2015. https://www.mlb.com/news/marty-noble-heres-to-speedy-recovery-for-former-mets-pitcher-al-jackson/c-123092634

15 Ron Darling with Daniel Paisner, The Complete Game: Reflections on Baseball, Pitching, and Life on the Mound (New York: Alfred E. Knopf, 2009), 24.

16 Darling with Paisner, 25.

17 Jacobson, Chapter 8 (Kindle edition).

Full Name

Alvin Neill Jackson

Born

December 26, 1935 at Waco, TX (USA)

Died

August 19, 2019 at Port St. Lucie, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.