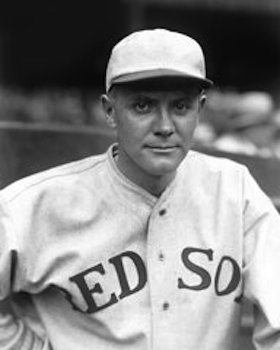

Bennie Tate

“It went about half way up in the right-field stands. It would have been a home run anywhere. … Ruth either hit a knuckleball or a curve. I really don’t know. All I can remember is watching the ball disappear.”1 The batter was Babe Ruth, hitting his 60th home run in 1927. The pitcher was Tom Zachary of the Washington Senators. Washington catcher Bennie Tate recalled the day. “We didn’t think too much about it at the time. We thought he would probably beat 60 later. I would estimate that Babe would hit 15 to 20 more home runs a year with today’s ball. He didn’t hit too many cheap shots. But I remember one year when he was contending for the batting title and the third baseman was playing in; Babe was just trying to punch it into left field past the third baseman and punched it into the left-field stands.”2 Tate may have recalled a more active role in the proceedings than he himself personally had. Muddy Ruel was Zachary’s catcher that day.

“It went about half way up in the right-field stands. It would have been a home run anywhere. … Ruth either hit a knuckleball or a curve. I really don’t know. All I can remember is watching the ball disappear.”1 The batter was Babe Ruth, hitting his 60th home run in 1927. The pitcher was Tom Zachary of the Washington Senators. Washington catcher Bennie Tate recalled the day. “We didn’t think too much about it at the time. We thought he would probably beat 60 later. I would estimate that Babe would hit 15 to 20 more home runs a year with today’s ball. He didn’t hit too many cheap shots. But I remember one year when he was contending for the batting title and the third baseman was playing in; Babe was just trying to punch it into left field past the third baseman and punched it into the left-field stands.”2 Tate may have recalled a more active role in the proceedings than he himself personally had. Muddy Ruel was Zachary’s catcher that day.

Bennie Tate was a catcher, and a smallish one at that (5-foot-8 and 165 pounds), who played in 10 major-league seasons. He hit four home runs of his own, and hit for a .279 career average – very good for a catcher in a time when catchers weren’t looked to for offense. He drove in 172 runs in 566 games, for four teams, most of the time working for the Washington Senators. Small he may have been for a catcher, “but he had plenty of scrap,” read his Sporting News obituary.3 Tate was right-handed but batted left-handed.

His full name was Henry Bennett Young Tate and he was born in Whitwell, Tennessee, on December 3, 1901. He described himself as of Scotch/English ancestry but said that his maternal grandparents were one-quarter Cherokee.4 He attended school for eight years, and that was it.5 Tate’s father Marion Lester Tate was a coal miner and the family had moved to Edgewater, Alabama. Young Benny took a job as a machinist in the mines, and in 1916 – when he was just 15 – also got started playing third base and the outfield, and catching a few games, for the Edgewater town team in the Tennessee Coal and Iron Co. league, playing semipro ball there in 1917.6 The family moved to Ohio, where he worked again in the mines “250 feet down and a mile in.”7 And on they moved to Herrin, Illinois, for more work in the mines.

He was reported to have gotten work with a semipro team out of Missouri and was given a trial with the St. Louis Browns. Tate went to Tulsa and worked as a Browns farmhand in 1920, transferred to Rock Island from there. He dated his own professional career to 1921 with the Rock Island Islanders in the Class-B Three-I League. He caught in just 27 games (Charlie Connolly handled most of the catching duties), but batted in 99 games, hitting .270. He homered two times. Outfielder Al Schweitzer was the only other player on the team to make the majors. Rock Island finished in last place.

In 1922, he was recalled by the Browns and assigned to Mobile but he refused to report and returned to playing semipro ball. After he was released, he signed with Memphis in 1923 and hit .263 in 93 games. Later in the season, his contract was sold to the Washington Senators. Scout Joe Engle was given credit for his signing.8

In 1924, he opened the season with the Washington Senators. It was a good year to be with Washington. Bucky Harris and his team won the American League pennant, beating the Yankees by two games. Walter Johnson’s 23-7 record went a long way toward achieving first place. Tate’s first three appearances – one each in April, May, and June – each resulted in one hitless at-bat. His first start came on July 1 in the second game of the doubleheader against the visiting Red Sox. Right-hander Curly Ogden threw a three-hit shutout. He clearly caught a good game; at the plate, he was 1-for-3, with his first major-league base hit.

Tate drove in his first run during the second game of the July 5 doubleheader against the Yankees. Firpo Marberry was pitching; he took a 7-2 loss. Tate was 2-for-3, with the one RBI on a Texas leaguer behind the shortstop. He appeared in 21 games, with 43 at-bats, drove in seven runs, and hit for a .302 batting average. No less a figure than future Hall of Famer George Sisler (manager of the St. Louis Browns at the time) was impressed by his work and in mid-August said that he “looks like a coming star.”9 His progress, however, was blocked by first-string catcher Muddy Ruel.

Tate appeared in three World Series games (Games Three, Five, and Seven) and holds an unusual statistic – he had one plate appearance in each game, and each time drew a base on balls. With the N.L. champion New York Giants holding a 3-0 lead in Game Three, the Senators scored one run on a sacrifice fly in the top of the fourth, then reloaded the bases. The pitcher, Marberry, was due up. Senators manager Bucky Harris had Tate pinch-hit for Marberry. He walked and drove in a run. In Game Five, he pinch hit in the top of the ninth, and walked, but was left stranded on the bases. The final game, Game Seven, saw him pinch hit in the bottom of the eighth. The score was 3-1 Giants. Tate walked again, this time loading the bases. A pinch runner replaced him at first base. Harris singled and drove in two, tying the game. The game went into extra innings, and Washington won it in the bottom of the 12th.

Tate had begun 1924 marrying Mattie Pauline Russell in January. The couple had two children, George and Marilyn.

Tate played for the Senators again in 1925, and was again their third catcher, though he was used less frequently in 1925 (16 games). He drove in seven runs again, and he was 13-for-27, hitting for a .481 batting average. The team played in the World Series, but he was not called upon. Already in mid-1925, the Washington Post‘s Frank H. Young observed that Tate “cannot be expected to improve any while sitting close up on the bench. He has lots of natural ability and has hit fairly well on the few occasions he has been allowed to show his stuff.”10

Beginning in 1926, Tate become the second-string catcher and so saw much more duty. He appeared in 59 games. He hit .268, drove in 12 runs, and walked 15 times while striking out only once. One of those RBIs won a game, though. On August 11, his hit in the bottom of the 11th beat the Yankees. He received as presents “a gold wristwatch, an overcoat, $20 in gold,” and what were described as “other trifles.”11 The year after that – 1927 – Tate played in 61 games and hit for a .313 average, with 24 RBIs.

Ruel experienced a lame arm during spring training in 1928. He was still seen as the superior catcher with a “slight edge over Tate in handling pitchers and is a little steadier in the pinches, due to his greater experience.”12 Tate played most of April and May, but Ruel was out-hitting Tate .305 to .231 at the end of May. On July 1, Frank Young wrote a column describing Tate as discouraged that he was continually passed over in favor of other catchers, that he was always the bridesmaid and never the bride. Young suggested that manager Bucky Harris “does not rate the little receiver as ‘smart’ in baseball.” Clearly, Young said, Tate proved he was good as a hitter, but he couldn’t get the experience he needed behind the plate and was always waiting for a tomorrow that never came.13 He hit .246 for the season.

Tate’s 1929 season saw him rebound at bat, appearing in more than half the games and hitting .294. He drove in a career-high 30 runs.

In 1930, Tate was traded to the Chicago White Sox (with pitcher Garland Braxton) for first-baseman Art Shires. Tate was, in Shirley Povich’s estimation, “a reserve catcher long recognized as capable of holding down a regular berth on several major league clubs not as well fortified in backstop talent as the Nats.”14 The White Sox saw the lefty Braxton as the main feature of the trade; the Chicago Tribune‘s Edward Burns called Tate “a good catcher.” 15

The year 1931 saw him as the main man behind the plate for the White Sox. He played in 89 games, more than in any other year, and he would have played in more but for a bad day on September 5. In a game against the visiting Detroit Tigers, two White Sox players suffered broken bones. Right-fielder Carl Reynolds broke his ankle and Tate broke the middle finger on his right hand. Tate was only out three weeks, though, returning on the 26th with a 3-for-5 game that helped boost his final average to .267. He drove in 22.

Frank Grube and Bennie Tate were expected to be the catchers for the White Sox in 1932. He only played four games for Chicago. On the 29th, he was traded to the Boston Red Sox (with Smead Jolley) in exchange for catcher Charlie Berry and outfielder Jack Rothrock. At essentially the same time, Johnny Watwood went to Chicago for the $7,500 waiver price. The Red Sox were reluctant to let Berry go, but believed they’d be adding to their offense overall. Tate became Boston’s primary catcher and appeared in 81 games, batting .245. He drove in 26 runs, and hit two home runs in the one season, half his career production (he’d homered once in 1926 and once in 1927). Again, as in 1926, an 11th-inning base hit won a game, this time against the Indians on August 28.

In December, it was already known that the Sox were seeking someone else. The Boston Herald‘s Burt Whitman wrote, “Tate is a veteran and has his best days back of him.”16 Tate was only 30 years old.

The Red Sox really wanted to get right-hander Walter Brown. He’d been 19-12 for Montreal (2.89 ERA) in 1931 and 12-11 (3.68) in 1932. Outbidding both the Giants and the Phillies, they traded five players to acquire him, sending Tate to the Royals along with John Michaels, Urbane Pickering, and two players to be named later. The Sox retained options on Michaels and Pickering, but Tate was dealt outright.17 Brown never made the majors; Tate hit .335 in 118 games for Montreal in 1933 (before breaking another finger in mid-August) and spent most of the next four seasons there.

There was still time for one more stint in the big leagues. On December 15, 1933, the Chicago Cubs bought rights to his contract. They wanted him as backup to Gabby Hartnett.

He had his eye on other things, though. In mid-January he filed to run for sheriff of Franklin County, Illinois, running on the Democrat ticket. (He had lived for years in West Frankfort, Illinois.) If elected, he said, he would retire from baseball.18 Without researching Franklin County polling results, we can perhaps conclude he came up short. He spent spring training with the Cubs and most of the season with them. He appeared in eight games in May, two in June, and one in July. He wasn’t hitting well at all, only .125, when on August 6, the Cubs brought back Bob O’Farrell (who had first played for them in 1915) and gave Tate his unconditional release.

Tate returned to Montreal, and hit .349 in 25 games. In 1935, he played in 85 games for the Royals (hitting .274) and in 1936 in 82 games (hitting .258).

In the offseasons Tate had done work building the game. He was “supervisor of baseball in the WPA recreational program and has been organizing clubs and leagues throughout Southern Illinois.”19 He took off 1937 from baseball entirely, and devoted himself to this effort.20

Beginning with the 1938 season and for three years, Tate managed the Mayfield club in the Kitty League (Kentucky-Illinois-Tennessee), a Class-D farm club of the St. Louis Browns. As manager, he assigned himself a fair amount of work, playing in 89, 57, and 43 games, batting .317, .298, and .338 respectively. The Mayfield ream finished fourth in the eight-team league in 1938, but finished first in 1939 (though losing out in the second round of the playoffs); they finished fifth, though still with a winning record, in 1940.

During the offseason, he worked as owner of a gas station in Mayfield.21 In 1941, the Browns asked him to manage the Class-B Meridian (Mississippi) Eagles in the Southeastern League. Again, he assigned himself work in 59 games; he hit .257. The team finished in sixth place.

There was a moment of controversy in August, when he was fined $25 by the league president for a “ruckus” and “near riot” following a game with Montgomery, essentially charged with failing to provide sufficient police protection at the Meridian ballpark.22 His last year as player or manager was 1941.

SABR’s Scouts Committee shows that Tate scouted for the Browns in 1950 and 1951. Later in life he became part-owner of Carroll and Tate, a firm dealing in restaurant and bar supplies and equipment, including janitor supplies. From 1962 to 1966, he was treasurer of Franklin County.

Tate had been ill for a couple of years and suffered a heart attack near the end of October, 1973. He died on October 27, at Union Hospital in West Frankfort. He was survived by his wife Pauline, son Charles B. Tate, daughter Marilyn Morgan, brother Cecil, and four grandchildren.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Tate’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, and the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 “Bennie Tate, 70, Recalls Historic Day Behind Bat,” UPI story datelined September 28, 1972. The portion of the quote beginning with “Ruth” comes from The Sporting News, November 17, 1982.

2 “Bennie Tate, 70, Recalls Historic Day Behind Bat.”

3 The Sporting News, November 17, 1982.

4 Bennie Tate player questionnaire, National Baseball Hall of Fame. He spelled his nickname as “Benny,” as did most of the newspapers of the day.

5 Bennie Tate player questionnaire, National Baseball Hall of Fame.

6 Hartford Courant, January 24, 1932: C7.

7 Ibid.

8 Frank H. Young, “The Ivory Hunters of Baseball,” Washington Post, June 2, 1929: SM3.

9 Washington Post, August 18, 1924: S2.

10 Washington Post, June 20, 1925: 14.

11 Richmond Times Dispatch, August 13, 1926: 10.

12 Washington Post, April 4, 1928: 15.

13 Washington Post, July 1, 1928: 19.

14 Washington Post, June 17, 1930: 1.

15 Chicago Tribune, June 17, 1930: 17.

16 Boston Herald, December 10, 1932: 6.

17 Boston Herald, February 23, 1933: 7.

18 State Times Advocate (Baton Rouge), January 15, 1934: 13.

19 Evansville Courier and Press (Evansville, Indiana), June 22, 1937: 15.

20 Evansville Courier and Press (Evansville, Indiana), February 19, 1937: 18.

21 Cleveland Plain Dealer, November 17, 1939: 19. United States Census, 1940.

22 Macon Telegraph, August 8, 1941: 22.

Full Name

Henry Bennett Tate

Born

December 3, 1901 at Whitwell, TN (USA)

Died

October 27, 1973 at West Frankfort, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.