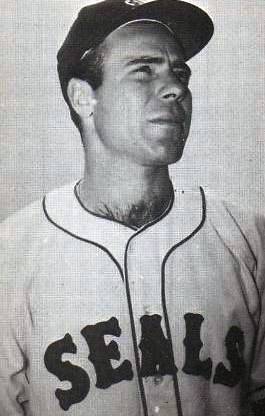

Bob DiPietro

Bob DiPietro’s major-league career was a true cup of coffee – 12 plate appearances in four games at the tail end of the 1951 season, one hit, one walk and a .091 batting average. In three games as an outfielder, he had four putouts, one error, and one assist – but what an assist it was! He threw out Mickey Mantle at home plate at Yankee Stadium.

Bob DiPietro’s major-league career was a true cup of coffee – 12 plate appearances in four games at the tail end of the 1951 season, one hit, one walk and a .091 batting average. In three games as an outfielder, he had four putouts, one error, and one assist – but what an assist it was! He threw out Mickey Mantle at home plate at Yankee Stadium.

DiPietro’s adventures before embarking on his professional career are probably worthy of more mention. They involved “resigning” from the Navy to pave the way for an encounter with Ty Cobb and Babe Ruth.

Robert Louis Paul DiPietro was born on September 1, 1927, in San Francisco, the son of Angelo and Relsa DiPietro. Angelo was an immigrant from Italy who by the time of the 1930 Census owned a barber shop in San Francisco. Relsa was a native Californian whose parents came from New York. Their first-born was a daughter, some eight years older than Bob. DiPietro was a standout pitcher and outfielder and also played football and basketball and boxed at San Francisco’s Abraham Lincoln High School. After graduating from high school in 1945, he enrolled at San Jose State University, and planned to enter the Navy. How he wound up in the Army instead of the Navy is a story in itself.

As he told it in an interview: “I decided I was going into the Navy. I knew that I was going to get drafted. I hadn’t signed up, so I went to see the recruiter. At that time Esquire magazine had an annual game where they picked a team of [high school players from] east and west of the Mississippi River, brought them back to New York and played at the Polo Grounds. I happened to win (a preliminary) game in San Francisco and they selected me. I had a chance to go back to see the recruiter in the Navy, and he said, ‘No, no you can’t take that trip, we have an agreement, you’re going into the Navy.’ I said, ‘Did I sign anything? You still have the papers, but not my signature, I’m out of here.’ I went to the Army guy and I told him my situation, and he said, ‘See me when you come back and we’ll put it all together.’ ”

DiPietro then embarked on a trip across the United States to play in the 1945 Esquire Magazine All American Boys Baseball game. The two managers were Hall of Famers, Babe Ruth and Ty Cobb. All of the players stayed in New York for 10 days, and worked out together in preparation for the game. DiPietro found himself in the unexpected position of captain of the Cobb-managed West team. “He called me in my room, [and told me] I was elected captain of the West team. Nobody knew each other. He called and told me about the election and that he wanted to talk to me about that and how I should carry myself. There were some good ballplayers there. One went to the Giants, he played second base [Davey Williams]. Another was a left-handed pitcher, the one I got a hit off, he went to the Phillies [Curt Simmons].” The East won the game, 5-4.

While reminiscing about the game, DiPietro spoke about being in awe of baseball’s immortals. “… Talk about a dumb kid who was in awe of his surroundings and never got any autographs. … It was interesting because Babe Ruth, who never got confused with the area minister, had on a gray sweatsuit. I can still see him. We were in the Polo Grounds, and during batting practice, he grabbed the bat from one of the players and told the kid, ‘Get the hell out of the batting cage, you aren’t worth a shit as a hitter.’ He said, ‘Carl, groove a few of ’em here, let me show them how to hit.’ Carl Hubbell was pitching! I look back, Cobb, Ruth, Hubbell, and what did I get? Zip! Ruth hit six balls into the stands. It was the damnedest exhibition I’d seen. And he was in a sweatsuit, but he had that great swing. Of course the Polo Grounds, it was very short down both lines, but he hit a good drive into center field. He put on a show; it was great.”

As a member of the West squad, DiPietro tried to get Cobb to open up about his career.

“He wasn’t the friendliest. Both of those guys were disappointments as individuals to me. Cobb did sit in the lobby on a couple of occasions and told us stories of his career and how he and Joe Jackson were tied for the batting championship in the last day of the season, and he knew that Shoeless Joe was a temperamental guy. They would say hello as they changed innings. He said, ‘I decided to get into Joe’s head, and he said, “Hi, Ty,” and I just ignored him. I saw him turn and look at me. Next inning, I did the same. He went 0-for-4, I got three hits and won the title.’ This was the kind of guy he was.” (An interesting story, but untrue. The Tigers and Indians didn’t play each other in the last series of the season; Cobb sat out the last three games to protect his batting average; Cobb and Jackson were never tied; in fact, Cobb led Jackson from the beginning of the season to the end.)

After returning to California, DiPietro began his tour of duty in the Army. “I was in right at the end. I stayed Stateside and was in for only 13 months. My father had died, and I got out on a dependency discharge in 1947. The war was over. It was just a matter of mopping up. The scout that signed me for Boston, Charlie Wallgren, he arranged for us baseball players to get on the baseball team. (At) Camp Stoneman in Pittsburg, California, the general in charge of that camp was a baseball fan/nut and had a weak baseball team. He got hold of a few of the guys as we came through. We were supposed to go to Korea, so all of the baseball players came in. I got in line, took my turn, they asked me my name, checked my record, they said, ‘You’re in the medics and on the baseball team.’ There was a fellow by the name of Tommy Brown of the Brooklyn Dodgers who was also on that team. We had a pretty good ballclub. We had 14 days off before we had to report back to camp. We played the team we were going to join, we won 28-0. We were welcomed with open arms by the general. That’s where I spent all of my time. Seven weeks in training and the balance was at Camp Stoneman. I never denied that. I wasn’t interested in being a hero if I didn’t have to go risk my life. If the war had been on, it would have been different, but everyone else was buttoning up. I got back in February of 1947 and I went to spring training.”

And so it began for DiPietro, as he made his start in 1947 with San Jose of the Class C California League, where he batted .312 with 21 homers, primarily as an outfielder, but a little bit at third base. The next year, he made the leap to Class A Scranton (Eastern League). With his advancement in the minor-league system came a new position for DiPietro, second base. DiPietro described how the move to the infield presented itself. “It was discouraging because we saw Ted Williams in left, Dom DiMaggio in center, and our only hope was Clyde Vollmer in right. And Vollmer had a good season too! [Actually, Vollmer didn’t come to Boston until 1950.] They came to me and said look, Bobby Doerr is going to retire next year and we want to send you to Scranton to play second base to replace Doerr. They saw me play second base and that ended that experiment!” (DiPietro’s memory lagged here, too; Doerr didn’t retire until after the 1951 season.) In another interview, DiPietro further reflected on his second-base experiment. At San Francisco in 1956, DiPietro played under the watchful eye of future Hall of Fame second baseman Joe Gordon. He said he might have been a better second baseman if he had had the help of Gordon back in 1948. He discussed his speculation in Brent P. Kelley’s The San Francisco Seals, 1946-1957. “I would have loved to have been able to do that with Joe Gordon ’cause I think he could’ve taught me how to play that position and maybe I could’ve. I don’t know. I never did feel that I could’ve cut it at the major-league level as a second baseman, but I didn’t get hurt in the year that I played there.”

DiPietro spent the 1948, 1949, and 1951 seasons at Scranton. He was with the Double-A Birmingham Barons (Southern Association) in 1950. After posting three consecutive seasons (1949-51) of hitting .300 at the minor-league level, DiPietro was called up for his “cup of coffee” at the end of the 1951 season. He found himself with a front-row seat to a pennant race between the Yankees and the Red Sox, with the Red Sox, under manager Steve O’Neill, five games out of first place with nine games left, six of which were against the Yankees. The Sox lost all nine games and wound up in third place.

DiPietro appeared in four of the nine games and went 1-for-11 with one single and a walk. He clearly recalled his first major-league at-bat. It was against the Yankees on September 23, the first of the nine games. “It was in Fenway Park. I pinch-hit for Dom DiMaggio. The first guy I faced was Vic Raschi, and he walked me. Yogi Berra was catching. I stepped in, a young punk and it was like a who’s who. Raschi was having a great year. The umpire said, ‘Hey Yogi, here’s a goombah of yours, he’s a dago kid, why don’t you tell him what’s coming?’ Yogi said, ‘Oh geez, Al, if I did that, old Vic would kill me. I can’t do that. I ain’t gonna call no curveballs.’ Raschi walked me on four pitches. He was obviously scared to death!”

DiPietro earned his nickname, the Rigatoni Rifle, by throwing out Mickey Mantle at home plate at Yankee Stadium. Jokingly, he said, it was “all downhill after that.”

That series against the Yankees bought DiPietro his place in the Hall of Fame, or his signature at least. “Allie Reynolds pitched his second no-hitter [of the season] against Boston. I’ll never forget that. Ted Williams was the guy he had to get out. He popped him up at home plate. Berra lost the ball in foul territory and Reynolds came running in yelling at Berra and he lost the ball. He had to get Williams out again, he popped him up again over by the Yankees’ dugout and Berra made one hell of a play. As a result of that, they took the pitching rubber and had everyone on that team sign it, including the rookies, as it was the end of the year, so we all marched into the Hall of Fame.”

In his short time in the major leagues, DiPietro said, he received quite an education playing in Yankee Stadium. The education came from two unlikely sources: Hank Bauer and the Yankees fans. DiPietro described a meeting before a game he had with Bauer once the pennant was wrapped up. “Bauer came up to me, and said, ‘If a ball’s hit down the line and it’s rolling, don’t try to cut it off, because if it gets in this circle – he took me over and pointed to the right-field foul area — it will roll right past you and [you will] look like a damn fool!’ He showed me where to go so that it would come right to me. I said to myself, what a heck of a thing to do! He wasn’t going to hurt the ballclub. The Sox were struggling to stay in third place. I’ll never forget that as a young rookie. The fans were an education for me, too. They knew how much I hit and why I was a bum. They shouted, ‘Hey DiPietro, what are you doing up here? You hit .297, I could hit that much!’ It was great.”

That was the last DiPietro saw of the major leagues. He continued to play until 1959 with Birmingham, San Antonio, Louisville, San Francisco, and San Diego before retiring with Portland at the end of the ’59 season.

At Louisville in 1953, he found himself playing with two All-American quarterbacks, Harry Agganis (Boston University) and Larry Isbell (Baylor). Agganis was a first baseman and Isbell a catcher. “Al Richter was my roomie, one of the two guys I hear from at Christmas. He was one of those guys who was an outstanding shortstop, but hitting was his problem. He had no chance behind Pesky.” There was one open spot in the outfield. “All of us, (Charlie) Maxwell, (Gene) Stephens, were vying for that one spot. They liked Stephens because he looked like Williams, tall and slender.” DiPietro played 78 games in the outfield that season. His batting average plunged to .205. The next season, he moved to hometown San Francisco of the Pacific Coast League, making a salary greater than the major-league minimum of $7,500. He found playing in the PCL more enjoyable than in the American Association. “The conditions were much better,” he said. “There were some awfully good cities in the Coast League. We’d go for a week at a time. When we’d play Hollywood and Los Angeles, we’d stay in the same hotel for two weeks. We flew most of the trips except to Oakland.”

At San Francisco, he said, “It was an interesting mix of ballplayers. You had those who were probably not going back to the majors but had spent time there, and others who did have a chance [to make it]. It was good competition and good baseball. Most of us younger guys felt like we had a shot. I loved it. I know a few players that extended their careers by being in the Coast League because the conditions were so good. There weren’t that many overpowering pitchers in the Coast League. There were those who were crafty. Ewell Blackwell joined us in San Francisco for a while. You could see how tough he was based on his delivery. By the time he joined us, he couldn’t throw that hard. His fastball still moved and sank and he threw the occasional knuckleball. He was able to get by based on his knowledge of how to pitch when he could not blow the ball by the hitters anymore.”

DiPietro his .269 with the Seals in 1954. In ’55, playing in 64 games, he batted an astounding .371. One would think this might have paved the way for a return to the big leagues, and, according to DiPietro, it almost happened, until fate intervened. “From what I had heard, there was a deal that was all put together with Kansas City. One night, I tried to stretch a double into a triple, and I broke my leg. That was the end of my year. That was one of those years you couldn’t do anything wrong. You just had to swing it and it would go in between someone.”

DiPietro was able to play one season of winter ball toward the end of his career, with Maracaibo (Venezuela) in 1957. His roommate was a young Maury Wills, a Dodgers farmhand who had not yet reached the major leagues. “The Dodgers sent him there to learn how to switch-hit. What a difference that made! They labeled him Phantasma. They called him that because he stole everything that wasn’t nailed down! A lot of those Venezuelan pitchers went into very fancy movements and a long delivery process. We said to him, ‘OK, Maury, you’re gonna steal two bases at one time.’ We had a young pitcher who went through all kinds of rigamaroles, and Maury tried it. He got halfway past second base and had to go back.” Wills went on to set a record for stolen bases in a season (which has since been broken), swiping 104 bases in 1962.

When interviewed by Kelley for his book on the Seals, DiPietro said his best experiences in baseball were with San Francisco: “When all is said and done, that’s really the highlight of my baseball career – the years spent with the Seals. I just enjoyed them so much.”

His broken leg robbed DiPietro of much of his speed, necessitating a move to first base for much of the remainder of his career. He averaged .264 for his last four seasons in the PCL, retiring after the 1959 season with Portland. He moved to Yakima, Washington, and worked in TV advertising sales and then opened his own advertising agency in 1967. He ran the agency until he retired in 1999, and turned it over to his oldest son Bob Jr., who was a first-round pick of the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1974 out of Stanford University. The younger DiPietro suffered a career-ending elbow injury and after an unsuccessful surgery, he followed his father’s footsteps into the advertising arena.

Sources:

All sources not cited come from personal interviews with Bob DiPietro on November 2, 2008, and December 3, 2009.

All statistics are courtesy of the database at Baseball-Reference.com.

Kelley, Brent P., The San Francisco Seals, 1946-1957: Interviews With 25 Former Baseballers. (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2002).

Full Name

Robert Louis Paul DiPietro

Born

September 1, 1927 at San Francisco, CA (USA)

Died

September 3, 2012 at Yakima, WA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.