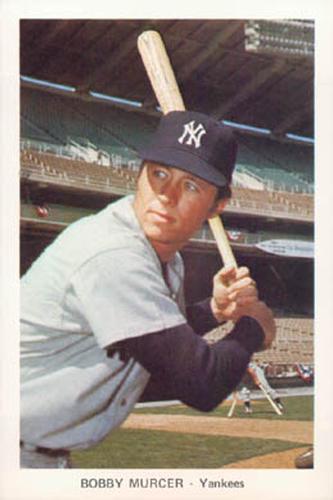

Bobby Murcer

As a boy, he rooted for the New York Yankees. Before he became an adult, he was playing for them. Although he left the club for a time, it never left him, and when he got the chance he did not hesitate to return. For the past twenty-five years, in one way or another, he has continued to be a part of the Yankees. He is a man who said that if he had to choose between election to the Baseball Hall of Fame or being honored with a day at Yankee Stadium, he’d pick the latter.

As a boy, he rooted for the New York Yankees. Before he became an adult, he was playing for them. Although he left the club for a time, it never left him, and when he got the chance he did not hesitate to return. For the past twenty-five years, in one way or another, he has continued to be a part of the Yankees. He is a man who said that if he had to choose between election to the Baseball Hall of Fame or being honored with a day at Yankee Stadium, he’d pick the latter.

Bobby Ray Murcer was born May 20, 1946 in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. He was the second of three children, all boys, born to Robert and Mae Belle Murcer. Robert owned a jewelry store. Bobby loved sports from the time he was a young boy. Although he was small, he was skilled enough to make the football, baseball, and basketball teams as a sophomore at Southeast High School. In his junior year, he made the all-district football team; at 145 pounds he was the second lightest player so honored.(1)

He also helped the Spartans to the conference championship in baseball, going three for three with a triple in the title game. (2) By the time he was a senior, he was probably the best high school athlete in the city, if not in all of Oklahoma. He made All-State in both football and baseball while he was All-City in basketball. Murcer was the leading scorer in the state in football and in the conference in basketball. While he was honored as a halfback, he also starred on the football team as a quarterback, linebacker, and punter. In baseball he mainly played shortstop while also pitching occasionally. He was a good enough running back to earn a football scholarship to the University of Oklahoma.

However, Bobby thought his future lay in baseball. As a sweet-swinging shortstop, he attracted the attention of many major league teams. Although the Dodgers offered him a much larger bonus, Bobby’s favorite team was the New York Yankees. After the team brought him to Kansas City to work out with them for a day, he signed a contract with Yankees’ scout Tom Greenwade for a $10,000 bonus in June 1964. He chose to invest most of it in his father’s store, as well as his girlfriend’s father’s grocery. (3)

The Yankees assigned him to their Johnson City affiliate in the rookie level Appalachian League. Murcer adapted quickly to professional ball, with a .365 batting average to his credit by the beginning of August 1964. Unfortunately, he then suffered a knee injury that ended his season prematurely and led to his first trip to New York, to be checked by the Yankees’ team doctor. This would prove to be his only serious injury, although he suffered from tendonitis in his right shoulder throughout his career. The knee healed in time to allow Murcer to play in the Florida Instructional League in September. His play that first year was impressive enough to earn him recognition on the post-season Appalachian League All-Star team at shortstop and to have the Yankees add him to their 40-man roster to protect him from the first year player draft. He returned to Oklahoma City over the winter and worked in his father’s store, as he would do for several more years.

In 1965, Murcer attended spring training with the Yankees before they optioned him to Greensboro, in the Carolina League. There he continued to thrive (.322, 16 home runs), being voted the league’s Most Valuable player and Topps Player of the Year, and was also on the Topps Class A (East) All-Star team. At the end of the 1965 season, the Yankees recalled him, and he got into eleven games for the club in September. His first Major League hit, in his second game, was a game-winning home run. He also played on Mickey Mantle Day on September 18 at Yankee Stadium. Mantle was his boyhood idol, and he would later describe playing alongside Mantle in that game as the greatest thrill of his career. (4)

The Yankees’ shortstop, Tony Kubek, retired after the 1965 season, and the 19-year-old Murcer was a candidate to replace him. Ralph Houk, Yankees’ general manager, called Murcer “one of the finest young players I’ve ever seen.” (5) Bobby was making fans off the field, too, with his personality. One writer called him “instantly likeable” and predicted he would become one of the most popular Yankees “because his charm is irresistible.” (6) Although the Yankees obtained veteran infielder Ruben Amaro to compete for the shortstop job, Murcer played well enough early in spring training to become the front runner. However, he slumped once it looked like he had the job locked up, and manager Johnny Keane decided to split the position between Murcer and Amaro. That plan had to be scrapped almost as soon as the season started, as Amaro suffered a severe knee injury and was unable to play again until September.

Since the Yankees didn’t believe Murcer was ready to play full-time for them, they moved third baseman Clete Boyer to shortstop, with Tom Tresh taking Boyer’s spot at third base. After three weeks of mostly sitting on the bench, Murcer was optioned to Toledo of the International League, where he could play every day. He had another good season, playing in the All-Star game and hitting four consecutive home runs in a double header.

At 160 pounds, he wasn’t really considered a slugger, but more a good line drive hitter. Murcer hit out of an extremely closed left-handed stance then, which he later abandoned for a less extreme stance and a slight crouch. He was recalled by the Yankees in September, and got into twenty games with them. He hit poorly in the American League, but the Yankees weren’t worried about his bat. Murcer himself said that once he saw Major League pitching for a few games, he knew he could hit it. His fielding was another story. Although he had shown rapid improvement, raising his fielding average in two years from .775 to .939, his defense was clearly behind his offense. His Triple-A manager, Loren Babe, said that while Bobby had “excellent range and a good arm,” he had problems on balls hit to his right and on charging grounders. Murcer himself felt his errors were a result of “stupid mistakes and relying too much on my arm.” (7)

During the off-season, Bobby married his high-school sweetheart, 18-year-old Diana Kay Rhodes (known as Kay). He would later tell a story that his father told him to pick out any wedding rings in his store. After Bobby chose the most expensive rings in the inventory, his father surprised him by presenting him with a bill. His reasoning was that if Bobby was ready for marriage, he could pay for the ring. (8)

Murcer also attended Central Oklahoma State College, majoring in physical education. He went to Florida a week early in 1967 to take part in a golf tournament, and to get an early start on spring training. He expected to win the Yankees’ shortstop job, but fate threw him a curve. On the day he reported to the Yankees’ camp in Fort Lauderdale, Kay called to tell him that he had received his draft notice from the army. Bobby spent most of the next two years in the military, serving in the radio corps at Fort Huachuca, Arizona. Kay was pregnant when he was drafted, and gave birth in the fall to their daughter Tori Keleighn Murcer.

Bobby had little opportunity to play baseball while in the army, but it did not seem to hurt him. While on leave in 1968, he played seven games in the fall Instructional League and slugged 1.000, before a wrist injury put him on the shelf. He played a couple of those games at third base, and after his discharge from the army, played third for Caguas in the Puerto Rico League. There he continued hitting, driving in eighteen runs in twenty-two games.

While Murcer was in the service, the Yankees regularly discussed moving him to another position. In the spring of 1969 they had him compete for the third base job with incumbent Bobby Cox. Murcer had gained 15 pounds in the military, mostly muscle in his upper body. He won the starting spot with a great spring, and headed into opening day wearing uniform number one, using what had been Mickey Mantle’s locker (Mantle had retired that spring), and hitting third in the Yankees’ lineup.

This would seem to be a lot of pressure to place on a twenty-two-year-old going into his first full Major League season, but if Murcer felt it, he didn’t show that he did. He got off to a great start, hitting 5 homers and driving in 17 runs in the Yankees first nine games. Initially, his fielding was good, too, but after a few weeks, he suffered a jammed right thumb. It didn’t affect his hitting, but he started making throwing errors.

On May 12, in Seattle, Murcer got into a fight with Pilots shortstop Ray Oyler, and both were ejected along with Houk, now the Yankees’ manager. Tom Greenwade, the scout who had signed Murcer, said that Bobby had a bad temper in high school. (9) However, being in the army had matured him, and this was to be the only ejection of his big league career. (10) While they were in the clubhouse, Houk instructed Murcer to practice in right field before the next game and that if he felt comfortable there, it would be his new position. He did and it was.

Murcer continued his hitting, leading the major leagues in RBIs through Memorial Day. However, on that day he hurt his ankle running the bases, and had to sit out a few days. When he returned to the lineup, his timing was off, and he started chasing bad pitches. His hot bat turned ice cold through the next two months. He hit only two home runs with a .200 batting average during the months of June and July. On August 5, in a game he didn’t start, he socked a game-winning three-run homer, and thereafter he refound his stroke. Over August and September, he slugged .530. He also fulfilled Arthur Daley’s prediction, being voted Most Popular Yankee by the Catholic Youth Organization.

On defense, Murcer struggled initially after moving to right field (in his first game, he bobbled the only ball hit near him) but he improved enough by late August to start playing center field part time. After September 10, all of his starts were in a center. By the following year, he had learned the position well enough to lead the league in assists with fifteen (the first of four such titles) while only committing three errors.

The Yankees had a somewhat disappointing year in 1969, declining three wins from 1968 to 80, and Murcer’s final numbers (.259, with 26 home runs and 82 RBIs) weren’t what he was hoping for after his hot start, but he had established himself as a regular. He followed that with a busy off-season. For the only time in his career, he spent the winter in the New York City area, except for a few days in Miami serving as a baseball instructor at a country club (which he would return to several times) and an appearance on a World Series review telecast on an Oklahoma City station. He started training to become a stockbroker, but didn’t like it, and instead took a job in the Yankees’ public relations department. Also, Kay gave birth to a son, Bobby Todd Murcer (who goes by Todd.)

Bobby felt confident enough in his position to hold out for three days in the spring of 1970, before signing for an estimated $27,500. (11) This season would be a much better one for the Yankees, as they improved to 93 wins, although they still finished fifteen games behind the Baltimore Orioles. Murcer’s hitting was hot and cold again, though, and his final figures (.251, with 23 home runs and 78 RBIs) were close to what he had produced in 1969, except that he increased his walks from 50 to 87. He was never hotter, though, than he was on June 24, when he tied a Major League record by hitting four consecutive home runs. He did it in a doubleheader against Cleveland, hitting a homer in the ninth inning of game one off Sam McDowell and then three in game two off two Indians’ hurlers.

After the 1970 season ended, Murcer headed home to Oklahoma City, where he bought a part interest in a bookkeeping services business. He also made an appearance on the variety show Hee Haw, along with Mickey Mantle. Mostly what he did, though, was think. He was unsatisfied with his hitting, believing that he should be able to maintain a .300 batting average. To do that, he decided to stop trying to hit home runs, since he was never going to be a big slugger, and hit the ball where it was pitched instead. He also adopted a bat that was one ounce heavier than he had used before. In addition, Mickey Mantle worked with him the next spring to improve his bunting.

His new approach was an immediate success, as he led the Yankees in hits and RBIs in spring training. He said he was pleased with the number of hits he got to left and center fields. His hot hitting continued once the regular season began. After batting fourth the first two months, the Yankees switched him to the third spot to prevent opposing teams from pitching around him. Murcer was intentionally walked ten times in thirty-seven games hitting cleanup. With his new approach, he reduced his strikeouts by more than 40 percent, while walking more often, and he continued to hit for power. By the end of June, he had a .453 on base average and a .579 slugging average. In a poll of his peers, he was chosen for The Sporting News’ mid-year All-Star team. Fan voting for the All-Star game had him fourth among AL outfielders, but an injury to Tony Oliva allowed Murcer to start the game in center.

He cooled off somewhat in the second half, but remained among the league’s leading hitters. In September, he was briefly hospitalized with some small kidney stones, and soon after he returned to action he pulled a muscle and missed another week. These injuries didn’t keep him from putting on a late season charge, and he ended up hitting .331 with 25 home runs and 94 RBI, while leading the league in on base average (.427) and OPS (.969). Despite his hitting, the Yankees struggled around .500 all season, ending with an 82-80 record. Murcer made the post-season TSN All-Star team as the AL’s center fielder and was second in Player of the Year voting. Ted Williams called him the best young player in the league. (12)

After the season ended, he again returned to Oklahoma City, where he now owned a household chemical distribution company, and spent his spare time playing handball and golf, and lifting weights to keep in shape. Despite all the exercise, he reported to 1972 training camp five pounds overweight. Bobby was happy with that; he thought it would keep him from getting tired late in the season. The Yankees weren’t as happy, especially when he struggled in exhibition games. Just as he started to hit, the players went out on strike. Bobby stayed in Florida and continued to work out, but once the season got under way, about a week late, he wasn’t at the top of his game.

In May 1972 he only drove in two runs. He turned things around in June, but by mid-season, his numbers weren’t close to the previous year, though the fans still voted him a starter for the All-Star game. Like Murcer, the Yankees started out the season slowly, but they caught fire at the end of June, and by August they were only two games out of first place. This was the first pennant race of Murcer’s big league career, and he responded as the Yankees hoped he would, scoring and driving in twenty-seven runs in August. The team closed to within a half-game of first on September 12 before collapsing, going 5-12 to finish six and a half games out. Murcer ended up hitting a career-high 33 home runs and 96 RBI, while hitting .292 and leading the league with 102 runs scored. He also won the only Gold Glove of his career, being named one of three outfielders on the Rawlings All-Star Fielding team.

The 1973 season started poorly for Murcer. While in Puerto Rico to take part in the American Airlines Golf Classic, as he had the past two years, he tripped over his luggage and broke his right hand. He was in a cast for four weeks, and missed the beginning of spring training. The injury didn’t hurt him in his salary negotiations. Murcer had made an estimated $70,000 in 1972, and now felt he was ready to join the $100,000 class. The Yankees didn’t put up much of a fight, and Murcer became, at 26, the second youngest player to receive a six-figure salary. The only two Yankees before him to earn as much were also center fielders, Joe DiMaggio and Mickey Mantle.

Being in the salary class of DiMaggio and Mantle must have seemed natural to Murcer. He was constantly being compared his two predecessors at his position. Those comparisons generally didn’t bother him; he took them as a compliment. However, he naturally preferred to be recognized for what he had accomplished, and once said of his forerunners, “I just get tired of hearing about them. When a record gets warped, you have to throw it away.” (13) The comparisons to Mantle seemed particularly apt, since both players were from Oklahoma, both were signed by Greenwade, and both had started as shortstops before moving to center field. Murcer didn’t always fare second best in these comparisons, either. In his first four full years, he had hit more home runs than Mantle had. (Another way Murcer exceeded Mantle was on the golf course, where Bobby would consistently beat Mickey.)

His slugging continued in the first half of the 1973 season. After the second three-homer game of his career, July 13 against Kansas City, Murcer was tied for third in the AL with 19 home runs. Then, his power mysteriously vanished. He hit only 25 more homers the rest of the season and the next two. Also, his walks declined to fifty in 1973, down from ninety-one two years earlier.

Overall, Murcer had another good season, hitting .304 with 22 home runs and 95 RBIs, starting in his third straight All-Star game, and making The Sporting News‘ post-season All-Star team. He just missed winning another Gold Glove, finishing fourth among AL outfielders in the voting. The Yankees’ season somewhat paralleled their star centerfielder’s. The club surged in June, and was in first place as late as July 31. However, with Murcer’s power slump, the team could manage only a 20-34 record the last two months.

Murcer had a running feud with Gaylord Perry, the AL Cy Young Award winner in 1972. Perry had held Murcer to 2 hits in 20 at bats that year, mainly (Bobby thought) by throwing a greaseball. Murcer had some fun with Gaylord; he once caught a fly for the last out of an inning and spit on the ball before tossing it to Perry. Another time he sent Perry a gallon of lard. Perry retaliated by having a mutual acquaintance cover his hand with grease before shaking hands with Murcer and saying “Gaylord says hello.” Despite having better success with Perry in 1973 (nine hits in twenty-four at bats), Murcer’s complaints about the greaseball got him into trouble in late June when he commented that neither AL President Joe Cronin nor Commissioner Bowie Kuhn had the guts to stop Perry from throwing the pitch. Kuhn then proved Murcer correct by fining Bobby for telling the truth while doing nothing to stop Perry from throwing his illegal pitch.

1974 would be a year of many changes for Bobby Murcer, who at $120,000 was now the highest-paid player in Yankee history. He became the Yankees’ player representative in mid-May. Ralph Houk, his manager since late 1966, resigned, and Bill Virdon was hired to replace him. Bobby didn’t get along with Virdon, who Murcer felt didn’t treat him with the respect he’d earned as the team’s star player. (14) Virdon’s style was much colder than Houk’s, who constantly puffed up his players.

Yankee Stadium began a two-year renovation, forcing the Yankees to play their home games in Shea Stadium for the 1974 and 1975 seasons. Bobby didn’t find the new arena to his liking; the right field fence was thirty to forty feet deeper than the one at Yankee Stadium, and poor drainage in the outfield left him playing with wet feet much of the time. His power outage of late 1973 continued all season; he didn’t homer at Shea until September 21. Other than homers, though, he hit even worse on the road. He may have been letting his unhappiness affect his play. Certainly he was capable of hitting home runs at Shea; he hit four in ninety-seven at bats as a visiting player there.

Virdon, who had been an excellent defensive center fielder as a player, felt that newcomer Elliot Maddox was a better fielder than Murcer, and on May 28 moved Bobby to right field and installed Maddox as the regular center fielder. The switch seemed to help the Yankees, as Murcer excelled in right field, where he threw out twelve baserunners in his first fifty-two games.

As they had the two previous years, the Yankees contended for first place. This time, however, they didn’t fade at the end of the season. Murcer did his best to help the team win. On September 20, he tripled off nemesis Gaylord Perry to win the first game of a doubleheader, and the Yankees ended the day tied for first. His first Shea Stadium homer the next day tied the game as the Yankees came back from a seven to two deficit to win. Another round-tripper on the 22nd was the game winner and kept the Yankees one game ahead. If it hadn’t been for a great surge by the Baltimore Orioles, who won 28 of their last 34 games, the Yankees would have won the division title. After the close of play on September 29, with two games remaining, the Yankees were only a half game out of first. However, Murcer tried to break up a fight between backup catchers Rick Dempsey and Bill Sudakis and got a broken finger in the scuffle. He had to sit out the remaining games, which the Yankees split while the red-hot Orioles continued to win, and the Yankees finished two games out. Murcer ended the season hitting .298 with just 10 home runs but 88 RBI.

The biggest change of the year came a few weeks later. Although Murcer had been assured by principal owner George Steinbrenner that he would be a Yankee as long as Steinbrenner owned the club, and was told by team president Gabe Paul a few days earlier that he wouldn’t be traded, Bobby awoke on October 22 to find himself a member of the San Francisco Giants. The Yankees had traded his contract for that of Bobby Bonds, in the first ever exchange of $100,000 players.

The trade devastated Murcer. Since he was a boy, he’d wanted to be a Yankee. He’d achieved that dream, become the star of the team, and now he had to start all over, in a new league, clear across the country. From a pennant contender, he’d been sent to a team with a 72-90 record. His wife said later that he must have felt as though he’d been divorced. (15)

The Murcers found a house in Lafayette, northeast of Oakland, away from the cold winds that plagued Candlestick Park, where the Giants had their home games. Murcer hated playing there, and requested a trade as early as the summer of 1975. He called it the “worst place I’ve ever seen. It’s summertime everywhere around the United States but here . . . I’m just glad I don’t have to pay to get in.” (16) Once he tried keeping his bats in the clubhouse sauna until it was time to hit; the experiment failed when the pine tar on the handle melted. Despite his dislike of the place, Murcer hit well at Candlestick, with a career on base average there of .400. He won the National League Player of the Week award twice in a three-week stretch in late May and early June and was named to his fifth straight All-Star team.

Although he may not have been comfortable on the field, he made himself comfortable in the clubhouse, sitting in the rocking chair that had followed him from New York. Bobby became notorious for his use of a rocking chair. He had five more at home, and would take a nap in one after day games. The one in the clubhouse was rather short because the day after his first Shea homer back in 1974, teammate Sparky Lyle had sawed through the legs. Lyle reset the rocker so that Bobby couldn’t see it had been damaged, and everyone got a good laugh when he fell to the floor. The clubhouse staff was able to repair the chair, and it followed Bobby the rest of his career. The chair fit his easy-going attitude in the clubhouse, but it may have harmed his reputation, as some people thought he was too relaxed while playing, or that he didn’t work hard enough. During his years in San Francisco, there may have been some truth to this since he was so unhappy. Murcer even said that he felt that he was just visiting the National League teams he played on; he’d always be a Yankee in his heart. (17) The fact that the Yankees started winning pennants without him made him feel even worse, especially since the Giants were under .500 in each of his two seasons with the club.

Murcer’s request for a trade was finally honored on February 11, 1977, when he was sent to the Cubs in a multi-player deal that brought Bill Madlock to the Giants. The Cubs didn’t want to pay Madlock up to $200,000 per year over several years, but Murcer was crafty enough to realize that he had the Cubs over a barrel. They couldn’t afford not to sign him after trading Madlock’s contract for his, so Bobby negotiated his first multi-year deal, calling for $1,600,000 over five season. The pact made him the highest paid Cub player in history. He used some of the money to drill for oil and gas in Oklahoma City.

Even better, Murcer’s power stroke, which had returned in June 1976, came with him from San Francisco. With his help, the Cubs, who were 75-87 in 1976, had a great first half and led the league by seven and a half games by June 30. They were in first place for two months until August 6, but faded badly to finish at 81-81. Murcer was among the RBI leaders most of the season, but a poor September left him with disappointing final numbers (27 home runs, 89 RBI and a .265 batting average, all enhanced by playing in hitter-friendly Wrigley Field).

Despite his late fade, he was generally well regarded by the fans and the press. Bill Rigney, who managed Giants in 1976, said Murcer “gripes and moans, especially when he’s in a slump,” but he always hustles and has good baseball sense. (18) Writers often referred to him as a real professional, someone who did everything well, even if he didn’t excel in any one area or have the best natural ability. In his first year with the Giants, he set a San Francisco Giants record with twelve sacrifice flies. In 1976, he had pushed a bunt past a charging Cubs third baseman for a double which helped turn a 1-0 deficit into a 2-1 victory. On September 7, 1977, he alertly scored when home was left uncovered during a rundown.

That same 1977 season, he inadvertently became involved in a controversy even while he did a good deed. He spoke to a young, sick fan on the telephone before a game, and then hit two home runs that night. Keith Jackson, announcing the game for ABC-TV, reported that Murcer had promised a boy dying of cancer that he would try to hit a home run for him. However, the boy hadn’t known he was dying until that moment. The child passed away two weeks later.

The next year began auspiciously for Bobby, as he won the American Airlines Golf Classic, teaming with football player Bob Tucker. However, things didn’t go so well on the baseball field, as he slumped the first three months. His hitting picked up in mid-season, as his return to a closed stance propelled him to a .317 batting average for the final three months. His home run power disappeared again, and he hit only nine all season. The Cubs teased their fans once more with a pennant run; they were only two and a half games out of first on August 27, but they again collapsed to finish at 79 and 83. Murcer as usual returned to Oklahoma City for the winter, where he opened a chain of jewelry stores.

In 1979, he came under increasing criticism due to his lackluster play. Many people felt the only reason he was still playing regularly was his large contract. Cubs’ general manager Bob Kennedy had called Murcer’s fielding minor league quality in 1978, and when he missed a couple of routine fly balls in a spring training game, things got worse. In response, his teammates showed their support by voting Murcer team captain. This was an odd position for Murcer, who had always denied an interest in being a team leader, believing he didn’t have the right personality to take on such a responsibility. He tried to do a good job, instituting a “kangaroo court” in the clubhouse, fining players for minor infractions. In May, he was able to get the fans back on his side with a hot streak at bat, but when that ended, trade rumors swirled. Talks with San Diego and Los Angeles came to nothing. Murcer had a no-trade clause in his contract, so his approval was needed before he could be sent to another club. Finally, on the morning of June 26, Kennedy said the Yankees were interested in obtaining him, and wanted to know if Murcer would okay a deal. Bobby quickly said that he would, and a few hours later a trade for a minor league pitcher and a little cash made him a Yankee again. After telling reporters he felt like he was going home and had never been happier, he flew to Toronto and was in the starting lineup that same night.

His improved state of mind didn’t do anything for his hitting, however. He played fairly regularly for the Yankees, but by August 1, his slugging average was only .250. His fielding in center field also left a lot to be desired. There were fears that he was washed up. That day, the Yankees wrapped up a series in Chicago. Bobby stayed at the suburban home he was still renting with his close friends Lou Piniella and Thurman Munson. The next day the Yankees were off, and Munson returned home to Canton, Ohio, where he tragically died when he crashed his new jet plane while practicing takeoffs and landings.

Bobby and Kay flew to Canton, and spent the night comforting Thurman’s widow, Diane, and their children. Four days later, Bobby returned there for the funeral, and delivered one of the eulogies. He and his teammates went back to New York for a game that evening, and although he was tired, Bobby insisted on playing. With the Yankees trailing 4-0 in the seventh, Murcer hit a three-run homer, then came to bat in the ninth with runners on second and third and singled down the left field line for a 5-4 victory. It was his first home run since returning to the Yankees. Bobby put the bat he used in that game aside, and later gave it to Diane Munson. (19) The game seemed to serve as a catalyst for Murcer, who slugged over .500 from that day through the end of the season.

His hot hitting should have put him in a good position with the team heading into the 1980 season. However, he had to compete for playing time with several other left handed hitting outfielders such as Reggie Jackson, Oscar Gamble, and Ruppert Jones, the team’s new center fielder. In the first twenty-six games, he had only ten plate appearances. He spent more time complaining than he did playing. Bobby felt that he could still be a productive player, and feared that his career would come to an end without him having a chance to show what he could do. (20) He went around in such a funk that his teammates took to calling him “Black Cloud.” (His previous nickname, dating back to 1969, was “Lemon,” due to the shape of his head.)

He finally got a chance to play regularly against right-handed pitchers in late May, and from then until the end of July he drove in thirty-three runs in 122 at bats. This hot streak was sadly interrupted in June, when his father passed away. Bobby continued to hit fairly well the last two months, but in subsequent years his playing time steadily decreased. After the 1980 season, he went to the Florida Instructional League to learn to play first base, but he would never play there or or any other position in a regular season game the rest of his career. Following that, he traveled to Japan with an American League “All-Star” team. When he returned to the states, he ran a baseball school.

In 1981, it didn’t look like the Yankees would have a spot for Murcer on their team, but an injury to Reggie Jackson at the end of spring training saved his job. Bobby hit a pinch-hit grand slam home run on opening day in the Bronx, and received a huge ovation from the crowd. He stayed with the team the rest of the year, except of course that he went out on strike with the other players for two months. When the 1981 season ended, so did the big five-year contract he had signed with the Cubs.

He went back to Oklahoma, where he served as chairman of the board of an oil company, and waited to see if any team was interested in his services. He wasn’t picked in the free agent re-entry draft, but he had contract talks with Milwaukee, Texas, and a Japanese team. However, Bobby really wasn’t interested in changing teams, and accepted an offer to come to spring training with the Yankees without a contract. Reggie Jackson was gone now, and the team needed some left-handed power. Late in the spring, he was invited to the “Welcome Home Yankees” dinner. Bobby said “I think it’s a good sign that I officially got invited to the dinner, but they haven’t told me yet whether I’ll be sitting on the dais or waiting on tables.” (21) It turned out to be the former, as he signed a three-year, $1,125,000 contract with the Yankees. Some of the money he invested in race horses.

In 1982, Murcer continued to hit well off the bench, but only received 141 at bats, just five in the last two months. The following year, he once again had to worry about a roster spot. The Yankees put him on their AAA Columbus farm team’s roster over the winter, bringing him to spring training as a non-roster player. He quickly won a job by hitting safely in his first seven at bats in exhibition games. However, once the regular season started, he found himself in his familiar spot on the bench, occasionally pinch-hitting.

He found some time that spring to record two country songs, “Skoal Dipping Man” and “Bad Whiskey”, which were written for him by an acquaintance. The record was produced by Phil Ramone, and the Hudson Brothers sang backup. (22) Released by Columbia Records, it had some success, and Bobby even got to sing with Willie Nelson in a concert. However, he didn’t come near to the success enjoyed by his uncle (by marriage) Johnny Bond, a member of the Country Music Hall of Fame. (23)

Soon after the record was released, George Steinbrenner told Bobby that the Yankees needed his roster spot so that they could recall Don Mattingly. Murcer was just 4-22 in limited playing time that season. His playing career was now over. Steinbrenner offered Bobby a spot in the television broadcast booth, and Bobby accepted. He started that night on WPIX. He would continue with the station through the 1984 season. On August 7, 1983, the Yankees honored him with a “Bobby Murcer Day” at Yankee Stadium.

When he was fired from his television job, the Yankees hired him as an assistant vice president for 1985. One of his first responsibilities was supervising new Yankee Rickey Henderson’s injury rehabilitation in Fort Lauderdale after the team went north. While watching Henderson take batting practice, Murcer decided to take some too, and was swinging the bat well enough to contemplate a comeback. The Yankees allowed him to play four games for their Class A Fort Lauderdale affiliate, but a sore shoulder quickly ended any more thoughts of playing. Working in the front office for Steinbrenner didn’t suit Bobby, and the next year he was rehired as a broadcaster, working both on tv and radio.

In 1987, he was only part of the television crew as the season opened, and at the end of May found himself in uniform again, this time serving as a hitting coach for the Yankees. Oddly, since they were over the limit on coaches, during games Bobby had to wear “civilian” clothes and watch the games from the press box. Odder still, he only coached left-handed hitters, with full-time coach Jay Ward continuing to work with the right-handers. This arrangement lasted the rest of the season, and then Bobby returned to broadcasting. Except for 1990, he has been doing that ever since. He even passed up a coaching job with the Seattle Mariners when Lou Piniella managed them because he wanted to stay with the Yankees.

He has also continued his business career. In 1989, he purchased a part-interest in the Oklahoma City 89ers, a Triple-A team, and served as club president for several years. He started a telecommunications company in 1993. Along the way, he has found plenty of time to devote to his favorite recreation, golf, even joining two celebrity golf tours. In 1988, he took up running and entered the New York City Marathon. Although it took him more than five hours, he managed to finish the race. (24) Even with all these other activities, Bobby has been able to donate much of his time and effort to helping others. He headed a campaign to promote eye protection equipment for kids playing baseball. For charity, he has taken part in such activities as conducting the Oklahoma Youth Orchestra and a celebrity rodeo. He started a company to make baseball cards that charities could use to raise funds. Along with Kay, he has hosted parties to introduce the work of local artists to the community.

Two causes have been particularly dear to him. He serves as the chairman of the board of the Baseball Assistance Team, which grants money to former players and other baseball figures who are in need. In this capacity, he visits Major League teams during spring training, explaining the mission of the charity and soliciting funds. Bobby has called this work “probably the most important thing I’ve done in my professional life.” (25)

The other important calling he found was been his fight against cancer. In 1989, his older brother DeWayne died of lung cancer at forty-seven, and in 1995 his mother also succumbed to the effects of the disease. Both deaths were related to smoking. Bobby himself started smoking at the age of fourteen, later switching to smokeless tobacco, and appeared in ads for Skoal brand tobacco. To try to keep others from making the same mistakes, Bobby helped push through the Oklahoma legislature the Bobby Murcer Tobacco Addiction Prevention Bill, which increased fines for anyone selling tobacco products to minors.(26) In 1990 he began an annual golf tournament which has raised more than $1,000,000. (27) Much of the proceeds has been given to the American Cancer Society; some have been used to help fund an endowed chair for pediatric cancer research at the University of Oklahoma. For his good works, he received several citizenship awards, and was honored by being inducted into the Oklahoma Sports Hall of Fame. In late 2006, his battle against cancer became even more personal, as he had a malignant tumor removed from his brain. He died on July 12, 2008.

Bobby Murcer led a good life. He realized his childhood dream of playing for the Yankees, and even became one of the top players in the game. His wife noted that he was never single-minded in his pursuit of baseball fame, which suited her. She said, “If Bobby had pursued his career with the vengeance that some of them do … our marriage probably wouldn’t have lasted. I’m happy for the success he had because he got it and still remained a good father and husband.” (28) Even more, in 2003, he became a grandfather, as his daughter gave birth to a girl, Sophie. And he was a good citizen, trying to help others less fortunate than he.

End notes

(1) Daily Oklahoman, December 23, 1962

(2) Daily Oklahoman, April 23, 1963

(3) New York Times, February 25, 1967

(4) CenterStage on YES Network

(5) The Sporting News, February 19, 1966

(6) Arthur Daley, New York Times, March 1, 1966

(7) The Sporting News, July 23, 1966

(8) Sport, July 1975

(9) Gutman, Bill. At Bat! Aaron*Murcer*Bench*Jackson. Grosset & Dunlap, 1973

(10) Doug Pappas, private correspondence

(11) New York Times, February 28, 1970

(12) Washington Post, September 28, 1971

(13) New York Times, July 22, 1973

(14) The Sporting News, March 1,1975

(15) New York Times, August 15, 1982

(16) The Sporting News, July 12, 1975

(17) New York Times, June 27, 1979

(18) Chicago Tribune, February 13, 1977

(19) New York Times, June 23, 1983

(20) New York Times, April 25, 1980

(21) The Sporting News, April 10, 1982

(22) Daily Oklahoman, May 5, 1991

(23) Daily Oklahoman, August 3, 1947

(24) New York Times, November 8, 1988

(25) Madden, Bill, Pride of October, Warner Books, 2003, pp.285-7

(26) Daily Oklahoman, May 6, 1997

(27) Daily Oklahoman, May 19, 1999

(28) New York Times, August 15, 1982

Sources

Bashe, Philip. Dog Days. Random House, 1994

Gutman, Bill. At Bat! Aaron*Murcer*Bench*Jackson. Grosset & Dunlap, 1973.

Madden, Bill. Pride of October. Warner Books, 2003.

Munson, Thurman with Marty Appel. Thurman Munson. Coward, McCann & Geoghegan, Inc., 1978

Spatz, Lyle. New York Yankee Openers. McFarland & Co., Inc., 1997.

Piniella, Lou and Maury Allen. Sweet Lou. G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1986.

The Sporting News, various issues

New York Times, various issues

Washington Post, various issues

Retrosheet

Rocky Mountain News, March 16, 1997

www.mlb.com

San Francisco Chronicle, various issues

Chicago Tribune, various issues

Daily Oklahoman, various issues

Sport, August 1973, July 1975, May 1980

Sports Illustrated, April 28, 1969, July 4, 1977

Interview shown on YES Network

Full Name

Bobby Ray Murcer

Born

May 20, 1946 at Oklahoma City, OK (USA)

Died

July 12, 2008 at Oklahoma City, OK (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.