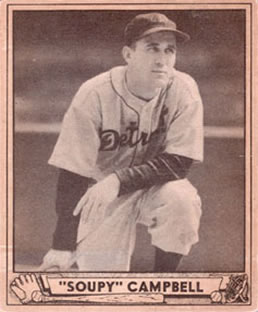

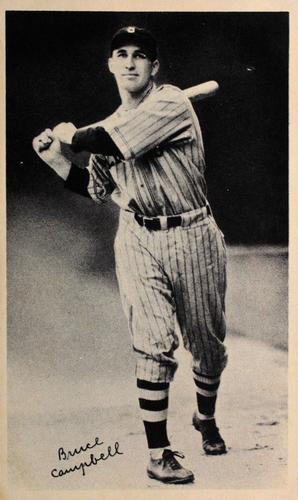

Bruce Campbell

Every team goes through it in every season. Untimely injuries test an athlete’s mettle as well as a club’s depth of personnel. Pitchers are hampered by a torn rotator cuff and sore shoulders, as well as the dreaded elbow maladies that may result in Tommy John surgery. Of course, position players are not immune to the injury bug. Pulled or torn hamstrings, twisted ankles, fractures in various parts of the body, can shelve a player for months or even a year.

Every team goes through it in every season. Untimely injuries test an athlete’s mettle as well as a club’s depth of personnel. Pitchers are hampered by a torn rotator cuff and sore shoulders, as well as the dreaded elbow maladies that may result in Tommy John surgery. Of course, position players are not immune to the injury bug. Pulled or torn hamstrings, twisted ankles, fractures in various parts of the body, can shelve a player for months or even a year.

Despite the severity of these assorted injuries, they are in most cases not life-threatening. The advancement of medicine, as well as the progression of physical therapy, have improved the recovery time of players. But none of that was true in the 1930s when American League outfielder Bruce Campbell was stricken with spinal meningitis, a bacterial infection that can attack the brain and spinal cord. If the symptoms are mis-diagnosed, it can lead to death within 24 hours.

Campbell survived not just one or two, but three attacks of the deadly disease and lived a full and healthy life. And when he enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Force to serve in World War II, he refused an assignment to stay on a base and play baseball. Instead, he transferred to a post as an engineer on B-24 bombers.

Bruce Douglas Campbell was born on October 20, 1909, in Chicago. He was the youngest of three children (sister Elizabeth and brother Russell) of Robert and Margaret (nee Shaffer) Campbell.1 Robert Campbell worked in an industrial paint store.2

Campbell was a three-sport star (football, basketball and baseball) at Lagrange High School. But it was baseball in which he excelled. After he graduated, he hoped to play professional ball, but he had no offers. So he followed his brother Russell (also known as Robert) and took a job running a printing press at Rand-McNally publishers.

While working at Rand-McNally, Campbell kept in shape by playing for the semi-pro Fernwood Boosters. In 1930 a White Sox fan named Michael Mikulas recognized his hitting ability and wrote to the Sox, urging them to sign the hometown talent. The White Sox brought Campbell to Comiskey Park for a tryout. They took a $400 a-month flyer on the green prospect and sent him to Indianapolis, which returned him after only two games. Sent to Bloomington of the Class B Three-I League, he batted .364 in 11 games.

The White Sox recalled Campbell and he made his major-league debut against Washington on September 12, 1930, at Comiskey Park, pinch-hitting for pitcher Garland Braxton in the seventh inning. He slashed an RBI single to right field and later scored on a home run by Carl Reynolds in an 8-7 loss.

In 1931 the White Sox instructed Campbell to report to Omaha of the Class A Western League. They also told Campbell that his salary would be sliced accordingly. To emphasize their point, the White Sox waived a release form in front of his face,

Campbell balked at their offer. Believing he had been released, he began sending telegrams on his own to different teams looking for tryouts. His first stop was Dallas of the Class A Texas League. But after only nine games, he was sent packing. Campbell finally got an opportunity with Little Rock of the Class A Southern Association. “Ray Winder was the general manager of the Little Rock ball club,” said Campbell. “Ray told me, ‘Young fella I know you can hit.’ They were doing so bad they put me in and I was finally able to get going.”3

In a pinch-hitting role, he got a game-winning hit in his first at bat. He was elevated to the starting lineup and played in 79 games, batting .383 in 300 at bats. When the White Sox recalled him in September, Campbell and Winder objected. The Sox claimed they had never released Campbell.4

Commissioner Landis settled the dispute, ruling in Chicago’s favor, returning Campbell to the Sox. He reported and hit two home runs in four games, but his stay in Chicago was brief. Nine games into the 1932 season, Campbell and pitcher Bump Hadley were dealt to the St. Louis Browns for utility player Red Kress on April 27. “It gives us what we need,” said Browns manager Bill Killefer. “A real right fielder and a pitcher who has proven one of the steadiest in the game.”5

Campbell had an inauspicious start with his new team. On April 28 against Detroit at Sportsman’s Park, He took the collar, going 0 for 4 with two strikeouts. In the field, he misplayed two fly balls and allowed one ball to roll through his legs for an error. His debut in a Browns uniform may have been overlooked as St. Louis won, 5-4.

However, in spite of the rough beginning, it was a breakout year of sorts for Campbell. The left-handed-swinging batsman finished second on the team to Goose Goslin in both home runs (14) and RBIs (85). However, with the good comes the bad: in his first extended play in right field, Campbell committed 22 errors. He also led the AL in strikeouts with 104. The joke around the team about Campbell was that he was capable of winning a ballgame with a tremendous homer and also putting the team in the loss column with his fielding.

St. Louis (63-91) finished in sixth place in the AL standings in 1932. When the Browns got off to a slow start in 1933, Killefer was relieved of his managerial duties and eventually replaced with Rogers Hornsby.

One of Campbell’s best offensive outputs to date occurred on July 1, a slugfest with Philadelphia won by the Browns, 15-14. Campbell went 3 for 4 at the plate, with two triples, five RBIs and three runs. He continued to be a productive hitter for the Browns, leading the team in home runs (16) and RBIs (106) while batting .277. He also cut down on his strikeouts (77). His defense improved somewhat, reducing his errors to 14 while leading the circuit in assists with 18.

The “Rajah,” as Hornsby was commonly referred to, was one of the great hitters in baseball history. “I’ll make a .300 hitter out of him in 1934,” he said. “Bruce goes after too many bad balls now. I’ll cure him of that.”6

Hornsby was correct on one count. Campbell reduced his strikeouts to 64 in 1934. But his power numbers dropped considerably (9 HR, 74 RBIs). The real problem with the Browns was their lack of starting pitching. Jack Knott (10-3) was the only Browns hurler to post a record above .500. But Knott was primarily a reliever and spot starter at best. It all added up to a sixth-place finish for St. Louis (67-85) in the AL standings.

Despite Campbell’s improvement in the batter’s box and in the field, St. Louis dealt him to Cleveland on November 21, 1934, in exchange for infielder Johnny Burnett and pitcher Bob Weiland.

Indians manager Walter Johnson inserted Campbell as his starting right fielder. With Earl Averill in center field and Joe Vosmik in left, the Tribe had quite a triumvirate of outfielders.

Cleveland (46-45-2) was scuffling in the middle of the pack in the AL when they traveled to Detroit for a three-game series on August 2. The first game was postponed on account of rain. Campbell, who was batting .325, was playing poker at the team’s hotel when he complained of headaches. He retired to his room to rest. He felt ill with flu-like symptoms the following day during the first game of a twinbill. “It was a full house that day and the game was tied. All of a sudden I started feeling woozy,” said Campbell. “I started walking towards center fielder Earl Averill, I said, ‘I can’t see too good. If a ball is hit to me, the game’s over.’ He said to see manager Walter Johnson and take myself out of the game.

“Johnson told me to go to the clubhouse. I kept thinking if I could only get back to the hotel. I went to the hotel and fell asleep. I woke up in the hospital with meningitis.”7

When the players returned to the hotel, they found Campbell in a deep sleep. However, he awoke at 4:00 A.M, vomiting. His roommate, Lloyd Brown, made calls to trainer Lefty Weisman and an ambulance arrived to take Campbell to Harper Hospital. There, he was diagnosed with spinal meningitis. A serum that was designed to isolate the meningitis and keep it from spreading was injected into Campbell.

A call was made to his family in Chicago. His mother and brother rushed to Detroit. The team of attending doctors had given him a 50-50 chance of surviving, and were even more alarmed when Campbell did not recognize his family members. Eventually, Campbell responded positively to treatment, as his temperature and pulse stabilized. He was released weeks later from the hospital. Although he was given a clean bill of health, restoration of his baseball career was in doubt. Campbell headed home to Chicago for a long recuperation. He relapsed with another attack in October while he was at home, further complicating and forestalling his comeback to a healthy body, much less baseball.

Part of his recuperation plan was to relocate to a warmer climate. “Earle Mack recommended that I try Fort Myers Beach the year before the last attack [in 1935], and I‘ve been here ever since, first in winter only, of course. But the climate has been wonderful and I’ve never had a hint of any more trouble.”8

Meanwhile, a decision was made in Cleveland to change managers. Johnson, who had been the Tribe’s skipper since 1933, felt that he was being undermined by Willie Kamm and Glenn Myatt. “They were a bad influence upon the ball club,” said Johnson. “Anyway, I let them go and a fresh storm broke out. Kamm took his case to Judge Landis. Why I don’t clearly understand. The newspapers made a big deal of it and even had me out of a job.”9

Indeed, the Indians fired Johnson and replaced him with Steve O’Neill, a former catcher with the Indians (1911-1923). O’Neill guided the Indians to a 36-23 record over the last couple months of the 1935 season. The Tribe (82-71-3) ended up in third place in the AL standings, 12 games behind first-place Detroit.

The Tribe arrived for a three-game series in New York beginning on April 28, 1936. In the last game of the series Campbell singled to center field. “I had singled to center at Yankee Stadium and Joe DiMaggio almost threw me out at first,” said Campbell. “When I finally got there, Lou Gehrig said, ‘What’s the matter, Bruce?’ I told him my legs felt like lead. ‘Gee, that’s tough,’ he said. ‘Do you think you’re getting it again?’ I told him the odds against having a second attack were a thousand to one and they had never heard of a third one.”10

The club headed to Boston. By this time, Campbell was feeling sick and again had flu-like symptoms and headaches. He was hospitalized and a second serum was injected into his spine, administered by Dr. William O’Halloran at St. Elizabeth’s Hospital. O’Halloran, a spinal disease specialist, was grim about Campbell’s prospects. “He’s a very sick boy,” said O’Halloran. 11

The entire Cleveland club was quarantined in Boston. Visitors were barred from the Indians dugout and the team walked from the hotel to the ballpark every day instead of taking public transportation.

Campbell made a speedy recovery and was released from the hospital on May 28. He spent some time recovering at home before reporting to League Park to begin working out with an eye to returning to the Indians. Joining Campbell in his workouts was a high school pitcher from Van Meter, Iowa, named Bob Feller. Scout Cy Slapnicka signed Feller to a contract when he was sixteen years of age, and there would be a hearing before Commissioner Landis on the legality of the signing. But for now, he was puttering around League Park, playing semi-pro baseball until he made his first start on August 23.

Campbell returned to the Indians in mid-June. He had one of his best days on July 2 at Sportsman’s Park. In the first game of a doubleheader against the Browns, he had six hits, tying a then-modern-day record for hits in a game, drove in five runs and scored a run in the Tribe’s 14-5 win. In the nightcap, Campbell singled in his first at bat. He then left the game from exhaustion. Although he played in only 76 games, and totaled 172 at bats, Campbell batted .372 for the fifth-place Indians (80-74-3).

Campbell returned to the Indians in mid-June. He had one of his best days on July 2 at Sportsman’s Park. In the first game of a doubleheader against the Browns, he had six hits, tying a then-modern-day record for hits in a game, drove in five runs and scored a run in the Tribe’s 14-5 win. In the nightcap, Campbell singled in his first at bat. He then left the game from exhaustion. Although he played in only 76 games, and totaled 172 at bats, Campbell batted .372 for the fifth-place Indians (80-74-3).

Campbell was selected as the “Most Courageous Athlete” by the Philadelphia Sports Writers Association for his courageous battle against spinal meningitis in consecutive years.

Over the next three seasons, Campbell was healthy again and for the first time played a full season in right field. Not only was he hitting well, but he cut down on his strikeouts, his walks outnumbering his whiffs. In 1938, Campbell put together a 28-game hitting streak from May 22 to June 22. In the streak, he batted .304 with four home runs and 28 RBIs.

In spite of his production, the Indians traded Campbell to Detroit for outfielder Beau Bell on January 20, 1940. Cleveland was looking for a right-handed bat to face southpaws. Campbell shared right field duties with Pete Fox. “That Campbell is the toughest man in baseball for the Detroit club to get out and I’m really glad to have him on our side,” said Schoolboy Rowe. “I was hunting with him in Arkansas this winter before the deal with Cleveland and I told him I had a good notion to shoot him just so I wouldn’t have to pitch against him again next summer.”12

Campbell was reunited with Averill, who had been dealt to Detroit the previous season. Rudy York was moved from catcher to first base, and Hank Greenberg was moved to left field. Stalwart Charlie Gehringer along with Barney McCosky and Pinky Higgins made for a tough offensive outfit.

Greenberg led the league in home runs (41), doubles (50), RBIs (150), and slugging (.670). McCosky led the league in hits (200) and triples (19). Campbell batted .283 with eight home runs and 44 RBIs. The Tigers were in a fight with Cleveland and New York for most of the season, clinching the flag on the last weekend in Cleveland, edging the Indians by a single game. It set up a date with Cincinnati in the World Series.

In Game One, Campbell had two hits, including a two-run homer, as Detroit won, 7-2. The Tigers took a 3-2 series lead after Bobo Newsom pitched Detroit to an 8-0 victory in Game Five. But the Reds stormed back, winning the final two games at Crosley Field to win the series. Campbell was 9 for 25 to lead all Detroit hitters with a .360 batting average.

After losing Greenberg to the military draft in 1941, the Tigers fell to a tie for fourth. Campbell batted .275 and was second on the club to York in homers (15) and RBIs (93).

Campbell was again on the move as he was dealt to Washington on December 12, 1941, for infielder Jimmy Bloodworth and outfielder Doc Cramer. The Senators (62-89) finished in seventh place in 1942, 39 ½ games behind first place New York. Campbell had a decent year at the plate (five HR, 63 RBIs, 278 batting average).

With World War II in full swing, many players joined the armed forces either by enlisting or via the draft. Campbell, enlisted in the United States Army Air Force after the Senators season concluded. He refused a stateside assignment, and instead was an engineer on B-24 bombers. It may appear curious that, given his medical history, Campbell would be accepted for military duty. “I didn’t tell ‘em,” said Campbell when the subject was brought up. 13

Campbell earned the praise of another pilot for his decision to forgo an easy assignment, instead choosing to take a combat position. The following was part of a letter written by an Army Air Corps pilot to Shirley Povich at the Washington Post and printed on July 27, 1948:

“Bruce Campbell, in my book, is some kind of hero. When he joined the Army in 1942, he was Bruce Campbell, the big leaguer; the 10-year man with a lifetime pass to the ball parks, a pretty good batting average and the holder of press clippings….

“…There was another player there, a big leaguer, and they were set to have a big season playing baseball in the Army. Campbell said to hell with it, requested a transfer to a field where he could become an aerial engineer and fly as part of a bombardment crew. His commanding officer, so the story goes, got sore…

“There were three to a ship, and the ship flew three periods a day, seven days a week, and furloughs were few and far between. Bruce Campbell didn’t have to do that. He could have been playing baseball. But he wasn’t. He did the nasty work. The dangerous work, and he had a choice.

“Bruce Campbell was interested in doing something about the war. And playing baseball wasn’t what he had in mind.”14

After Campbell was discharged in 1946, he reported to the Senators. He received a contract that was equal to the one he had signed in 1942, but was released after a few weeks. Campbell contended that the Senators did not give him enough time to get into shape following his extended absence from baseball. He sued the Senators for $9,000, claiming that, under the Selective Service law, he was entitled to a year’s employment at his old job. Washington owner Clark Griffith settled with Campbell for $6,000.

Campbell’s major league career came to an end. In 13 seasons, he batted .290, with 106 home runs and 766 RBIs. In 1,166 games in right field, Campbell fielded his position at a .955 clip.

Following his release from the Senators, Campbell returned to the minor leagues in 1946. He split the season between Buffalo of the AAA International League and Minneapolis of the AAA American Association, batting .270 in 64 games between the two clubs.

Retired from baseball, Campbell took up carpentry. He was now living full-time in Fort Myers. On July 13, 1961, Campbell married the former Adelaide Sweet. Together, they went into the real estate business in Estero Bay, Florida. The Campbells had no children.

Other than his business, Campbell lived out his life in anonymity. He enjoyed classical music and occasionally fishing from his home. Although he had a solid baseball career, he was reluctant to talk about it. He gave only a few interviews over the years.

Campbell contracted cancer and took his own life. On June 18, 1995, he was found dead at his home as the result of a self-inflicted gunshot wound, according to the medical examiner.15 Adelaide had preceded him in death 10 years earlier in December 1985.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Chris Rainey and Norman Macht, and reviewed for accuracy by SABR’s fact-checking team.

Notes

1 Campbell’s obituary mentions that he learned baseball in an Illinois orphanage. I could not find another reference that Campbell may have been adopted.

2 1910 United State Census

3 Joe Workman, “Bruce Campbell played game of hard knocks”, Fort Myers News-Press, January 20, 1991: 23A.

4 Ibid.

5 James M. Gould, “Kress traded for Campbell And Hadley in First Step To Strengthen the Browns”, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 28, 1932: 2B.

6 Henry P. Edwards, American League Service Bureau, December 31, 1933, Player’s Hall of Fame clip file.

7 Workman, 23B.

8 Lee Allen, “Cooperstown Corner”, The Sporting News, May 4, 1968: 6.

9 Scott Longert, No Money, No, Beer, No Pennants: The Cleveland Indians and Baseball During the Great Depression, Ohio University Press, Athens, Ohio, 2016, 243.

10 Workman, 23B.

11 Gordon Cobbledick, “Campbell Fights For Life Again”, Cleveland Plain Dealer, May 2, 1936: 1.

12 Workman, 23B.

13 Allen: 6.

14 Workman, 23B.

15 Joe Workman, “Player’s last inning in life a tragic end”, Fort Myers News-Press, June 21, 1995: B1.

Full Name

Bruce Douglas Campbell

Born

October 20, 1909 at Chicago, IL (USA)

Died

June 17, 1995 at Fort Myers Beach, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.