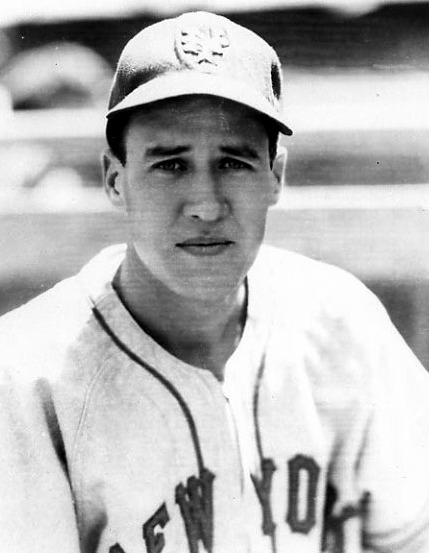

Buddy Blattner

Boxing and college football were regular fixtures on network television by 1953, but baseball was confined to local TV, with only the All-Star Game and World Series seen nationwide. While every team except Pittsburgh televised some games, the minor leagues were screaming that those telecasts were killing their attendance, and Congress was threatening legislation to limit them. Major league baseball had no television policy, leaving each team to decide how to deal with growing new medium.

Boxing and college football were regular fixtures on network television by 1953, but baseball was confined to local TV, with only the All-Star Game and World Series seen nationwide. While every team except Pittsburgh televised some games, the minor leagues were screaming that those telecasts were killing their attendance, and Congress was threatening legislation to limit them. Major league baseball had no television policy, leaving each team to decide how to deal with growing new medium.

In 1953 ABC-TV began the Game of the Week with the outrageous former Cardinals pitching star Dizzy Dean announcing alongside a little-known ex-infielder, Buddy Blattner. No recordings exist, but the first voice heard on baseball’s first weekly network television series was probably Blattner’s.

Buddy Blattner parlayed a short major-league career into a 26-year run as a broadcaster. His work as Dean’s “podner” on the Game of the Week was the highlight, but the partnership ended when he thought Dean stabbed him in the back. Blattner called play-by-play for four teams, showcasing “a sunshiny voice and his Rotarian of the Year personality.”1

No one-trick pony, Blattner was a popular NBA basketball broadcaster in his hometown, St. Louis, and founded a children’s charity that endured after his death.

Before baseball he was a two-time world table tennis champion in his teens. After baseball he won a national seniors tennis championship (without the table) in his 80s.

Robert Garnett Blattner Jr. was born in St. Louis on February 8, 1920, to the former Ethel Diercks and Bob Blattner, a salesman and fitness instructor at the YMCA. His father started calling him Bud when he was a toddler.

As he told it, the 12-year-old Bud practiced table tennis in a pool hall, laying boards over the pool tables. He graduated to a club managed by his father, where $1.25 a month bought unlimited playing time. He broke out at a tournament in Chicago when he was 15, defeating the defending national champion, Sol Schiff. Using what a writer called “hopping sidespin/topspin” shots, Blattner advanced to the finals before he was beaten.

At 16 Blattner and Jimmy McClure of Indianapolis, a former US singles champion, joined the American table tennis team that traveled to Prague in 1936. Blattner and McClure won the world doubles championship from the Czechs, overcoming partisan Czech fans who crowded around the tables. The pair was feted with a ticker-tape parade in New York when they got home. The American duo repeated the next year, beating the Austrian team on its home turf (table?) in Baden on Bud’s 17th birthday.

That same year Bud teamed with the world number-one women’s player, Ruth Hughes Aarons, the glamourous 18-year-old daughter of a Broadway producer, to win the US and English national championships in mixed doubles.2 Bud and another partner, Dolores Kuenz of St. Louis, lost in the world finals the following year. His younger sister, Marjory, was also a nationally ranked player. He was elected to the US Table Tennis Association Hall of Fame in 1979.

Young Blattner was a prodigy at regular tennis, too. Although he didn’t take up the game until his teens, he won the Missouri high school singles championship three times and twice won the Midwest Junior Davis Cup title.

Critics derided table tennis as a “sissy” game, but it requires hand-eye coordination and quick reflexes, the same tools needed to hit a baseball. Blattner lettered in baseball as well as tennis and basketball at Beaumont High. He went to Rogers Hornsby’s Baseball College in Hot Springs, Arkansas, where aspiring players paid $50 for six weeks of instruction by big leaguers.

The Cardinals’ general manager, Branch Rickey, signed Blattner out of a tryout camp in July 1938. “Judas Priest, son, you have the greatest coordination of any young man I’ve ever seen,” Rickey told him.3 He played eight games for the Double-A Columbus farm club, then returned home to finish high school and compete in table tennis tournaments during the winter. With his seventh-place ranking among American players, it’s a safe bet that he is the only professional baseball player to be nationally ranked at table tennis.

St. Louis sent Blattner to Class-B Decatur, Illinois, for his first full professional season in 1939. The youngest man on the team at 19, he played shortstop and hit .269. In 1940 he moved up to Sacramento in the Pacific Coast League, at the highest level of the minors. The next year his manager at Sacramento was Pepper Martin, his favorite player as a boy. Converted to second base, Blattner batted .294/.349/.448 with 17 home runs and 100 RBIs in 176 games. In August he and his hometown girlfriend, Barbara Jean Freimuth, eloped to Reno and got married.

Blattner won an invitation to the big league spring training camp in 1942. The first time he wore a Cardinals uniform, he remembered, “I almost broke both legs climbing out of the dugout, stumbling, fumbling and falling all over myself in my zest to play. I recalled the Knothole Gang days and how I worshipped the Cardinals and now I was a member of their fraternity.”4

Not for long. The 6-foot rookie opened the season as a late-inning replacement for his roommate, shortstop Marty Marion, who was often removed for a pinch-hitter. But Blattner went hitless in his first 13 major league at-bats.

Marion was batting .159 in mid-May when manager Billy Southworth benched him. Blattner started four straight games, delivering just one single in 14 at-bats, before Marion got his job back. That was Blattner’s only hit for St. Louis. The Cardinals sent him and his .043 batting average down to Rochester in June. At the end of the season the New York Giants claimed him on waivers.

The Giants would have to wait; Blattner enlisted in the navy in October 1942. He spent the war playing ball at Lambert Field in St. Louis and the Bainbridge Naval Training Center in Maryland, then joined an all-star team of professionals who entertained troops on Pacific islands in 1945. He played primarily with rackets and paddles on that trip in a series of tennis and table tennis matches against Bobby Riggs, a former US amateur and Wimbledon champion. Blattner got his first taste of broadcasting on Guam, reading sports news and interviewing other players over the Marines’ radio station.

Blattner was 26 when he joined the Giants for spring training in 1946. He made the team as a utility infielder, but soon took over second base because of an injury to Mickey Witek. When Witek recovered a month later, Blattner was batting above .300 and Witek shifted to third base.

In August a spinning pop fly split Blattner’s middle finger on his throwing hand. Manager Mel Ott got him a pay raise and pushed him to go back into the lineup, but his batting average nosedived. He finished at .255/.351/.405 in 126 games, showing speed and some power with 18 doubles, six triples and 11 home runs.

It was his only year as an everyday player. Bill Rigney beat him out for the second-base job in 1947, and in early 1948 the Giants sent Blattner down to their Triple-A club at Jersey City. Drafted by the Phillies in the fall, he spent his final season as a utility man.

Blattner’s 272-game major league career was his least successful endeavor, but it set up the rest of his life. Back home in St. Louis after the 1949 season, he created three baseball quiz shows for a local television station and decided that broadcasting was his future. He was hired to call Browns games on radio in 1950. The sorry club couldn’t find a sponsor until midseason, when Blattner began his long association with Falstaff beer.

Browns owner Bill Veeck, always looking for a crowd-pleasing stunt, hatched a scheme in 1951 to put Blattner on the roster, send him onto the field with a walkie-talkie strapped to his back, and have him broadcast a game while playing. The experiment died when the Phillies, who still owned Blattner’s contract even though he was retired, demanded $10,000. Veeck couldn’t afford it.

Blattner’s association with Dizzy Dean began when Dean joined him on the Browns broadcasts in 1952.5 Falstaff also put the two together for some of its national broadcasts on Mutual radio’s Game of the Day. They hit it off, because Blattner evidently was content to ride on Dean’s coattails.

Blattner realized he couldn’t trade on his skimpy resume as a ballplayer. He worked to make himself a polished broadcaster, not just another jock in the booth. He had a vibrant voice and developed an engaging, enthusiastic style. He talked to players, managers, and coaches, and inhaled the sports pages to gather information. “There’s an average interval of 15 seconds between pitches,” he told a writer. “You’ve got to fill some of that dead air. You can’t keep saying over and over that ‘the pitcher gets set on the mound, tugs at his cap, etc.’ “6

When the NBA’s Hawks moved from Milwaukee to St. Louis in 1955, Falstaff assigned Blattner to broadcast their games. Blattner had never called basketball and wasn’t sure what league the Hawks played in. He was not alone; the NBA in its early years was a hand-to-mouth operation.

Blattner’s play-by-play helped put the team on the map. “He studied the game and talked to the guys about the game,” Hawks center Ed Macauley said. “His delivery was great. His voice was always friendly. He was never screaming. Everyone liked him. He never took cheap shots at anybody.”7 Even while he was on network TV, Blattner was better known in his hometown as the voice of the Hawks.

Television was the hottest issue in baseball in 1953. Minor league teams were begging Congress to restrict major league broadcasts being beamed into their markets. When the majors moved to limit their telecasts, the US Justice Department began investigating whether the leagues were violating antitrust laws. (Of course they were.) The result was a free-for-all: every team for itself.

The catalyst for the Game of the Week was Falstaff, a regional brewery in St. Louis that was trying to build a national brand.8 Falstaff’s account manager at the ad agency Dancer, Fitzgerald & Sample was Edgar J. Scherick, who later created ABC’s Wide World of Sports. The young executive devised a way around the legal and political roadblocks: Black out the broadcasts in all major league cities and in minor league markets when the local team was playing on Saturday afternoons.9

Falstaff agreed to sponsor the games on ABC, which was a poor third in the ratings behind CBS and NBC. ABC negotiated contracts with individual teams; only the White Sox, Indians, and Athletics signed up at first. Several others declined for fear of a congressional backlash. The teams were paid a reported $14,000 each.

As faces of the Game of the Week, Falstaff chose the announcers from its Browns and Mutual broadcasts, Dizzy Dean and Buddy Blattner. The inaugural game, on Memorial Day weekend in 1953, saw the Indians beat the White Sox, 7-2. From Dean’s first appearance on network television, a star was born.

After a sore arm ended his pitching career at age 31, Dean began broadcasting in St. Louis. His unique version of the English language horrified some listeners and captivated others. As Dean described a game, players stood “confidentially” at the plate and “slud” into bases. Many viewers’ vivid memory is Ol’ Diz interrupting his play-by-play to sing “The Wabash Cannonball,” a country song made famous by his friend Roy Acuff.

“He enjoyed being a character,” Blattner said, “and he was smart enough never to get out of character.” Because of the blackout in major league markets, the Game of the Week audience was primarily in the South and West, perfect territory for Dean’s act. He was a Paul Bunyan and a Davy Crockett, a teller of tall tales whose deeds had been just as tall. In the same year the Game of the Week went on the air, Dean was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

“He didn’t just provide the program, he was the program,” Blattner said.10 Diz’s “podner” always maintained that he was happy being “that guy with Dizzy Dean.” Blattner understood that his job was to clean up after Dean, making sure viewers knew what was happening on the field while Diz was riffing.

From just 18 stations at the start, Game of the Week expanded to more than 100 by the end of its second year, producing excellent ratings. The more powerful CBS network took it away from ABC in 1955, expanding the audience further. After NBC horned in on the Saturday afternoon action in 1957, CBS added a Sunday game and NBC followed suit. CBS, with the popular Dean and a stronger lineup of teams, dominated the ratings.

As Dean’s star shined brighter, he threw his considerable weight around. Although the Game of the Week broadcast on only 26 weekends, he took off one of every five. CBS brass cringed when Dean insulted sponsors — especially airlines, because he hated to fly — and plugged shows on other networks. Once he advised viewers that they could watch a better game on NBC. But the ratings stayed high, and everyone knew why.

After the final Sunday game of 1959, the announcers were to go to Milwaukee to call the National League pennant playoffs on ABC. The Braves and Dodgers had finished the regular season in a tie, with the playoff series to start Monday.

Dean and Blattner’s partnership blew up in the next 24 tense hours. Chesterfield cigarettes, a cosponsor of the playoff games, didn’t want Dean because Diz had talked too much about the benefits of stopping smoking. Dean, in a snit, declared that if he couldn’t work the games, Blattner couldn’t, either. Falstaff gave in to the star and withdrew permission for Blattner to appear.

Blattner quit on the spot. “Diz can be charming, but he likes to push people around,” he said. “I made up my mind that he’d only do it once to me.”11 Dean denied what everybody assumed to be true. “I never pushed anyone around but them hitters,” he claimed. “I would never hurt Buddy.”12 The next time the ex-podners met, Diz acted as if nothing had happened between them.

Blattner walked away from a reported $50,000 salary. “I left, quite bluntly, the best job in the country,” he said later, “but it all evened up as the years went by.”13 The Hawks’ owner, Ben Kerner, persuaded Cardinals owner August A. Busch Jr. to add Blattner to his broadcast team in 1960. The Cardinals already had Harry Caray, Joe Garagiola, and Jack Buck in their booth. Buck was the odd man out, banished to a talk show until he rejoined the play-by-play broadcasts a year later.

After two years with the Cardinals, Blattner moved west in 1962 as the number-one broadcaster for the Los Angeles Angels in their second season as an expansion team. He joined his former weekend competitor Lindsey Nelson on NBC’s telecast of the 1964 All-Star Game and worked the NBC radio broadcast of the 1967 game.

When the majors expanded again for the 1969 season, the new Kansas City Royals hired an Angels executive, Cedric Tallis, as their first general manager. Tallis wanted Blattner as the team’s broadcaster, and Bud jumped at the chance to go home to the Midwest.

To find a second announcer, Blattner waded through 250 applications before he chose 26-year-old Denny Matthews, who had never broadcast professional baseball. Matthews had played varsity ball at Illinois Wesleyan University, and that was a big plus in Blattner’s eyes.

“He was a professor and a father figure,” Matthews said. Blattner assigned his protégé three innings and told him to find his own style: “If you try to be like me, we’ll just have a bad imitation of me.” Blattner counseled, “You have to tell people what happened and tell them why it happened.”14

Blattner chose well. Matthews was honored with the Baseball Hall of Fame’s Ford C. Frick Award for broadcasting in 2007. His current contract will take him through his 50th year as the voice of the Royals in 2018.

After seven seasons in Kansas City, Blattner left broadcasting in 1975. There were reports of a contract dispute, but he was tired of traveling and, at 55, felt disconnected from a new generation of ballplayers. “I always said I hoped I never stayed with this thing too long and became a cranky old man,” he explained. “I was burned out.”15

For his third career, Blattner moved into real estate development. He helped to create the Four Seasons Racquet and Country Club, a resort at Lake of the Woods in central Missouri, and served as its managing director.

He continued his involvement with the Buddy Fund, a children’s charity he founded in St. Louis. It began when the Hawks staged “Buddy Blattner Night” in the announcer’s honor. Instead of gifts, Blattner asked for donations to provide sports equipment for poor children. The Buddy Fund was still in business in 2016, working through organizations such as the Boys and Girls Clubs.

Blattner had given up tennis for most of his adult life, but went back to it while with the Royals when a couple of sportswriters challenged him — to their regret. He sharpened his game in retirement, winning more than 20 city and state Senior Olympics tournaments. In 2001 the 81-year-old Blattner won the National Senior Olympics singles championship in Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

Bud Blattner died at 89 of complications from lung cancer in Chesterfield, Missouri, on September 5, 2009. He was survived by Babs, his wife of 68 years, and daughters Barbara Lynne Young, Deborah Anne Knop, and Donna Jeanne Whitcomb.

Notes

1 Robert Gregory, Diz (New York: Viking, 1992), 381.

2 USA Table Tennis, “Robert ‘Bud’ Blattner.” http://www.teamusa.org/USA-Table-Tennis/History/Hall-of-Fame/Profiles/Robert-Bud-Blattner, accessed April 22, 2016.

3 Rick Hines, “Buddy Blattner, A Champion in Every Sense of the Word,” Sports Collectors Digest, February 22, 1991: 212.

4 Ted Patterson, The Golden Voices of Baseball (Sports Publishing, 2002), 116.

5 Dean had broadcast Browns and Cardinals games earlier. He spent an unhappy 1951 doing pregame and postgame shows for the Yankees.

6 Jerry Kirshenbaum, “And Here to Bring You…” Sports Illustrated, September 13, 1971. http://www.si.com/vault/1971/09/13/612765/and-here-to-bring-you-the-play-by-play, accessed April 24, 2016.

7 Obituary, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 5, 2009. http://genealogybank.com/doc/obituaries/obit/12A9B0D01456D150-12A9B0D01456D150, accessed February 18, 2016.

8 The history of the Game of the Week comes from James R. Walker and Robert V. Bellamy Jr., Center Field Shot: A History of Baseball on Television (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2008), 43-119.

9 Luke Ford, The Producers: Profiles in Frustration (Bloomington, Indiana: iUniverse, 2004), 465.

10 Curt Smith, Voices of the Game (South Bend, Indiana: Diamond Communications, 1987), 145.

11 “Sportscaster Quits Show,” Associated Press-Washington Post, October 21, 1959: B11.

12 “Dean ‘Never Pushed Anyone Around Except Hitters,’” United Press International-Washington Post, October 22, 1959: D5.

13 Smith, 163.

14 Denny Matthews, telephone interview, April 26, 2016.

15 Joe McGuff, “Exiting with Grace Is an Art in Itself,” Kansas City Star, August 24, 1984, in Blattner’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame library, Cooperstown, New York.

Full Name

Robert Garnett Blattner

Born

February 8, 1920 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

Died

September 5, 2009 at Chesterfield, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.