Danny Gardella

Today’s multimillionaire players probably don’t know Danny Gardella or the impact the wartime New York Giants outfielder had on their high salaries. Gardella’s brief adventure in the Mexican League and his challenge to baseball’s reserve clause was one of the first steps toward modern-day free agency.

Today’s multimillionaire players probably don’t know Danny Gardella or the impact the wartime New York Giants outfielder had on their high salaries. Gardella’s brief adventure in the Mexican League and his challenge to baseball’s reserve clause was one of the first steps toward modern-day free agency.

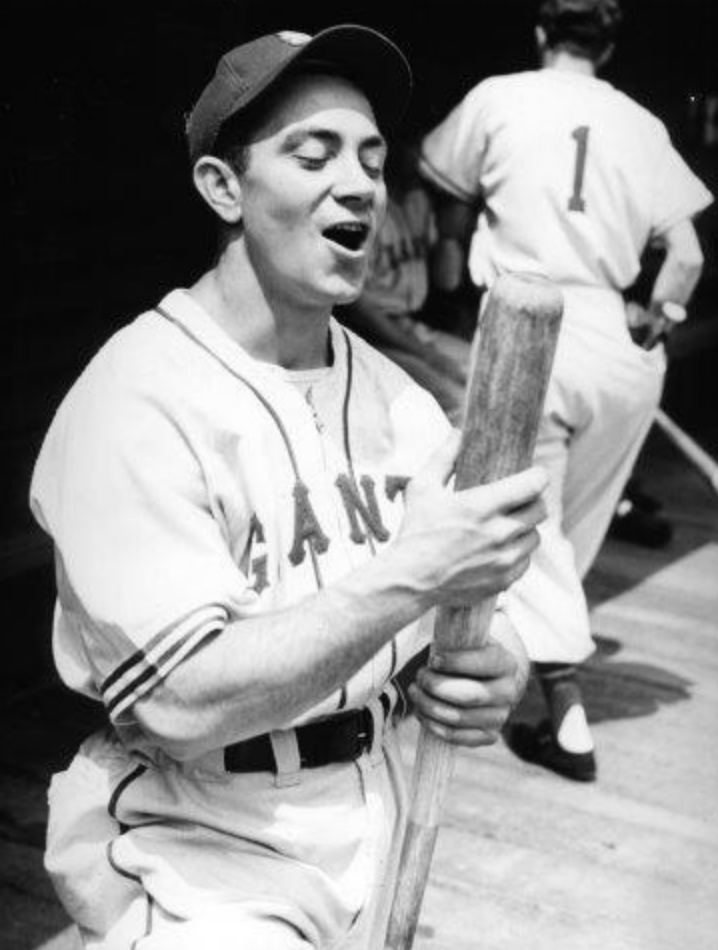

At a “not much taller than a fire hydrant” 5-feet-7 and a heavily-muscled 160 pounds, the left-handed pull hitter played all but one of his 169 major-league games in 1944-45, hitting .267 with 24 home runs and 85 RBIs.[fn] The “fire hydrant” quote comes from Jimmy Powers, “The Powerhouse,” New York Daily News, February 10, 1949.[/fn] Gardella was a singular character in the annals of baseball, one who earned a long list of nicknames: The Ignited Italian; Dauntless/Dangerous/Desperate Danny; the Mighty Midget; the Magnificent Busher; and the Little Philosopher.

Gardella was eccentric, colorful, and articulate, and his teammates never knew what he would do or say next. A voracious reader who often carried poetry anthologies, psychiatry tomes, and novels on road trips, he could quote Plato and philosophize for anyone who would listen. He was a fan favorite wherever he played, and often sang opera in a resonant baritone voice. Physically gifted, Gardella possessed enormous strength and could have been a professional acrobat. He could walk up stairs on his hands, do a triple midair twist while bursting into song, execute one-armed handstands, and do a two-legged split in the shower room. On long train rides, he would sometimes climb into a luggage rack above the seats and strap himself in with his belt for a nap.

A New York City native, Daniel Lewis Gardella was born on February 26, 1920. His father, Albert, was a mason who specialized in fancy inlaid marble floors for banks. His mother, Henrietta, an immigrant who arrived from Italy in 1912, stayed at home with Danny’s older siblings, Lillian and Alfred, and his younger sister, Rita. The Gardellas lived in the Fordham Road section of the Bronx; Danny attended Paul Hoffman Junior High and Roosevelt High School, and worked as a shipyard roustabout after school.

Danny and his brother Al (who also became a major leaguer) grew up playing with Bronx sandlot and club teams. Both signed contracts with Detroit before the 1938 season and were sent to Beckley, West Virginia, to play in the Class D Mountain State League. The second-place Bengals (61-52) upset pennant-winning Logan in the President’s Cup Playoffs. Danny hit .263 with four home runs in 113 games.

In 1939 Gardella was with the Class D Northeast Arkansas League’s Newport Tigers; his .352 average was fifth in the league after 35 games. Less than two weeks later, he was sent to the Kitty League’s Fulton Tigers, where he hit .227 in 75 contests.

Gardella’s Southern Class D league tour continued in 1940, first with Salem-Roanoke of the Virginia League, a Cleveland affiliate. After hitting .213 in 11 games, he was shipped to last-place Shelby (Tar Heel League), a Washington Senators farm, where he hit .252 with two homers in 37 games and place in the league’s All-Star game. He finished the year at Williamston, North Carolina (Coastal Plain League), where his average improved to .299 in 38 games. Gardella was so popular with local fans that special bleachers were constructed behind him in left field. However, by season’s end, Gardella could see the handwriting on the wall and, encouraged by manager Dixie Parker, decided to quit professional baseball.[fn] Dan Parker, “Young Fella, Gardella, Lifts Giants Out of Cella’,” New York Daily Mirror, June 3, 1944. [/fn] Other managers had previously told him that he would never make good in the game.

Gardella easily found work when he returned to New York. Over the next three years, he was an elevator operator and house detective at the New Yorker Hotel, a railroad yard freight handler, and a shipyard stevedore, and turned his physical-fitness fixation into a position as a trainer and masseuse at Al Roon’s Gym, sometimes helping chorus girls work off extra weight. Gardella had a short amateur boxing career and reached the 1940 Golden Gloves welterweight semifinals with four knockouts.

Gardella continued to play baseball, first for the New Yorker Hotel team in 1941 and then in the semipro Consolidated Shipyard League, where he hammered the ball throughout the summer of 1943. His manager, New York Giants scout Joe Birmingham, a former major-league player and manager, recommended him to Giants manager Mel Ott; Gardella was 4-F due to a punctured eardrum and couldn’t serve in the military. He signed a Giants contract on January 31, 1944. It was an opportunity he would have never received if there weren’t a wartime shortage of capable players.

At spring training in Lakewood, New Jersey, Gardella soon became known for walking the resort town’s streets loudly singing operatic arias in a rich baritone voice. Before an exhibition game on April 6, a number of baseballs were dropped from a Navy blimp from a height of 400 feet; Gardella caught one, which the New York Times called “no mean feat considering the near-freezing temperatures and a biting wind.”[fn] John Drebinger, “Ott’s Team Victor With 12 Hits, 12-3,” New York Times, April 7, 1944, 24[/fn]

Mel Ott kept Gardella on the Giants bench for the season’s first ten games before sending him to Jersey City on May 1. He hit .263 in five games with the Little Giants, driving in eight runs, before Ott brought him back as a replacement for injured outfielder Bruce Sloan. Gardella made his major-league debut on May 14 at Pittsburgh, going 0-for-4 in the first game of a doubleheader as Rip Sewell blanked the Giants, 1-0. He got his first hit, a triple off Nick Strincevich, in the nightcap. According to the Times, “Gardella … found himself up to his elbows in tough chances … in perhaps the most difficult right field pasture in either major loop.”[fn] John Drebinger, “Sewell Halts Giants in Tenth, 1-0; Pirates Also Take 8-2 Nightcap,” New York Times, May 15, 1944, 22.[/fn] He started again on the 16th, and the Times remarked that “Gardella almost flattened himself into eternity against the tricky right field wall in the second in a futile attempt to snare [ Johnny] Barrett’s three-bagger, but the plucky little fellow bounced back to give better than he received before it was over,” smashing a double in the first and an RBI single in the sixth.[fn] John Drebinger, “Weintraub’s Four Hits Lead Giants to Uphill 8-7 Victory Over Pirates,” New York Times, May 16, 1944, 25.[/fn] Back at the hotel after the game, Gardella donned a sports jacket, crashed a high-school prom, acquainted himself with the orchestra, and began to sing “Indian Love Call” to his startled audience before being ejected by the school principal.

In Chicago on May 17, Gardella was 3-for-4 with three runs, a triple, and two RBIs in a 10-6 win. By the time the Giants concluded their Western swing, Gardella sported a gaudy .375 average in eight games.

Fielding was another story. Gardella had never used sunglasses; during his first attempt, instead of flipping them down, he pulled his cap over his eyes, blinded himself, and almost got beaned. On another occasion, his pants were too loose, so he unbuckled his belt, only to look up and see a fly ball headed his way, which he ran after while holding up his pants with one hand, eventually picking up the ball with the other. He was particularly atrocious in a July 20 doubleheader in New York, misplaying three St. Louis balls into triples. Those he managed to snare kept the crowd on the edge of their seats. One sportswriter observed that “Gardella is the first guy since Babe Herman who provides more entertainment muffing a fly than catching it.”[fn] J.G.T. Spink, “Looping The Loops,” The Sporting News, June 15, 1944, 2.[/fn] On another occasion, The Sporting News wrote, “Gardella caught Litwhiler’s fly, unassisted.”[fn] Ibid. [/fn] Nevertheless, Danny, who had a .957 lifetime fielding percentage, was so popular that a large contingent of fans always hung a “Danny Gardella” banner from the Polo Grounds’ upper left-field balcony, which became known as Gardella Gardens.

Gardella also pulled pranks; a memorable one occurred during a July trip to St. Louis. Danny and Nap Reyes returned to their hotel room; Reyes adjourned to the bathroom to shave. Minutes later, noticing a strange silence, Reyes opened the door and found a note on his dresser: “I’m bored with life. So long. Danny.” The window was wide open and a frantic Reyes was horrified before checking it. There was Danny, hanging by his fingers from the window ledge, grinning as though it were a big joke. According to The Sporting News, “Other Giants, when they learned of the episode, shuddered, for the window was several stories up.”[fn] Oscar Ruhl, “From The Ruhl Book,” The Sporting News, July 13, 1944, 14 [/fn]

After playing on a regular basis through June 4, Gardella was a pinch-hitter or pinch-runner in 19 straight appearances from June 11 to July 9. Then he started in three more games, but on July 24, Gardella was optioned to Jersey City because of his fielding woes. In a brief return to the Giants, he played two games in Philadelphia on September 15 and 16. On September 17, Ott suspended Gardella for the rest of the season for breaking curfew; Gardella told Ott he disapproved of curfews. His season ended with a .250 average, 6 homers, and a .912 fielding percentage in 47 games.

Although the Giants, in the Times’ opinion, viewed Gardella as “something of a problem child” [fn] James P. Dawson, “Medwick, Rucker Sign With Giants,” New York Times, March 6, 1945, 26.[/fn] in 1944, he was back on the team in 1945. He continued to pinch-hit for his first ten appearances but made the case for more playing time on May 24 by smashing a two-run pinch homer in the eighth, securing a 7-6 win at Cincinnati. Other notable performances followed: 3-for-4 with four RBIs in a 7-2 victory over Philadelphia on June 16, another 3-for-4, four-RBI game on the strength of homers in two consecutive innings against Boston on June 20, and another two-homer, four-RBI game in a July 7 win against Cincinnati. Eleven days later, Gardella’s three-run, eighth-inning homer was the difference in a 6-3 victory at Pittsburgh.

On July 15 the Times offered this assessment: “Dauntless Danny right now is going great guns no matter where you play him. … (T)he conviction is growing that … for all his queer antics and occasional mental lapses, [Gardella] has the makings of an excellent ball player. He still runs the bases like an unbridled bronco on the range, but he does possess a powerful throwing arm, fields capably wherever he is played—they have now had him in left, right and first base—and his hitting has been no flash in the pan.” [fn] 0 John Drebinger, “Ott Shifts Line-Up To Bolster Giants,” New York Times, July 15, 1945, 1, 3 [/fn] During a 15-game Western swing from July 12 to 24, Danny hit .317, socked three homers, and knocked in 14 runs.

On May 16 the Giants purchased Al Gardella’s contract from Jersey City; he made his major-league debut the next day, in the first of 14 games he and Danny played together before Al was optioned to Birmingham of the Southern Association on July 7. They were one of nearly 100 sets of brothers who played together in the major leagues.

After a 6-3 win at Cincinnati on July 21, Gardella offered his opinion on the state of the game. “Baseball today … is too stereotyped. Everything is precision play and while the technique improves, the individual dash and verve of players which once made them standouts has disappeared. Take [Van Lingle] Mungo. … [S]ure he is a much smarter pitcher than he was ten years ago. But at the same time he no longer is the colorful guy he was ten years ago when every one came out to see him pitch.”[fn] John Drebinger, “Mungo Of Giants Checks Reds, 6-3,” New York Times, July 22, 1945, 49.[/fn]

Gardella specialized in game-winning homers during the season’s final two months. His two-run clout in the 13th secured a 4-2 win over Philadelphia on August 5. A week later, another two-run shot was the difference in edging Cincinnati, 3-2. On September 22, he broke a 2-2 tie with a walk-off, upper-deck wallop off Boston’s Don Hendrickson.

By season’s end Gardella had played in 121 games and posted a .272 average. His 18 homers were eighth in the National League.His .954 fielding percentage was an improvement from 1944, but his nine errors as an outfielder (fourth in the NL, despite playing only 94 games in the outfield) showed that he was still a liability afield.

Even with players returning from the war, the Giants offered Gardella a $5,000 contract for 1946. He had earned $1,900 in 1944, started 1945 at $2,200, and was boosted to $5,000 in midseason. Unhappy with the offer and believing he deserved a modest raise, Gardella missed the train to the Giants’ Miami training camp in 1946 and paid his own way, arriving in a foul mood. Shortly thereafter, he loudly clashed with Giants traveling secretary Eddie Brannick over a rule requiring a jacket and tie in the team dining room. Admonished by Mel Ott, Danny exited the premises vowing to leave the Giants in favor of playing in Mexico. Then, a few hours later, he was back, announcing that he was ready to sign the original offer. By this time, Ott had heard enough and washed his hands of the matter. Before leaving camp, Gardella told reporters, “You may say for me, that I do not intend to let the Giants enrich themselves at my expense by sending me to a minor-league club. They have treated me shabbily. I have decided to take my gifted talents to Mexico. … I would have accepted this figure had they not started to push me around.”[fn]“A Jolly Good Fellow, Baseball Magazine, February 1946, 29[/fn]

Frustrated, Gardella immediately contacted Jorge Pasquel, a wealthy Mexican customs broker he had met at Roon’s Gym during the winter. Pasquel was surprised that Gardella earned so little playing baseball that he needed winter work. He was in the process of organizing his Mexican League and offered Gardella a contract to play for Veracruz, giving him $5,000 to sign, an $8,000 salary, and an option for two more seasons. Another 21 major-league players followed, including fellow Giants Nap Reyes, Adrian Zabala, Ace Adams, and Sal Maglie. On April 16 the Giants placed Gardella on the ineligible list.

On Opening Day Gardella hit a two-run homer as Veracruz took a 12-5 victory over Mexico City; two losses followed when he lost two drives in the sun. He continued to hit well during the season’s first half, capping it by slugging two home runs in the Mexican League All-Star Game. By late June most American players in Mexico had become disillusioned. Mexican players resented the high salaries received by the Americans, who were dissatisfied with field and living conditions. In late June The Sporting News reported that “Danny Gardella [is] about the only happy player in Mexico.”[fn] “Most US Players Disillusioned in Mexico, The Sporting News, June 26, 1946, 14. [/fn] His play fell off during the second half; Veracruz slumped to the bottom of the standings. Lonesome, Gardella asked his girlfriend, Katherine Bonaventura, to join him from New York; the couple soon married in Mexico City. In 100 games, Gardella hit .275 with 13 home runs and 64 RBIs. A few hours after the final game, Pasquel told him that he would cut salaries for the 1947 season; revenues had failed to meet his projections.

In June baseball Commissioner A.B. “Happy” Chandler had barred any player who jumped to the Mexican League from returning to the major leagues for five years. He cited the reserve clause in the standard player contract, which bound a player to a team for life unless the team traded or released him.

Gardella and Katherine returned to New York after the Mexican League finale. Then he went to Cuba, where he hit .217 and was a reserve first baseman for Cienfuegos in the Cuban Winter League.

Back in New York during the summer of 1947, Gardella played for the Gulf Oilers, a Staten Island semipro team. Before a game with the Cleveland Buckeyes of the Negro American League, Commissioner Chandler sent a telegram to the stadium that was read over the loudspeaker: Any player caught participating in a game with Gardella or any other former Mexican League player would be banned from the major leagues for life. None of the Buckeye players was willing to take the risk and the game was canceled.

Disgusted and humiliated, Gardella hired lawyer Frederic Johnson, who was interested in his case because Gardella was blacklisted for violating the reserve clause rather than a player contract. Johnson and his family had ties to baseball going back to the 1880s and he had once written a United States Law Review article on baseball law. In October Gardella sued Major League Baseball, charging conspiracy to restrain free trade and using the reserve clause to deprive him of his right to make a living. Jumpers Max Lanier, Fred Martin, and Maglie filed suit shortly thereafter.

Banned from playing in the 1947-48 Cuban Winter League, Gardella returned to the island to play for the Cuba club in the Cuban Players League (also called Players Federation League), where he hit .250 and led the four-team circuit with ten homers. At home in New York, he earned a living with various blue-collar jobs, including factory work, truck driving, street sweeping, and working for a moving company.

In 1948 Gardella toured with Max Lanier’s All-Stars, a club that won all of its 80 games; he sang “Danny Boy” and opera pieces at many of the stops. Later in the season, and in 1949, he played for Drummondville (Quebec) of the independent Provincial League and had his best year (.283, 17 homers, 80 RBIs) for the league champion Cubs, whose lineup included such major leaguers as Lanier, Maglie, Vic Power, Tex Shirley,

Roy Zimmerman, and Negro League all-star Quincy Trouppe. Gardella played in the league All-Star game, and in the playoff finals his first-inning grand slam cemented a 7-0 victory over Farnham in a series Drummondville won, five games to four.

Meanwhile, in July 1948, Gardella’s suit had been rejected by a federal judge who cited the 1922 Supreme Court decision that baseball was not subject to laws governing interstate commerce. In February 1949 a federal appeals court overturned the judge’s ruling and ordered a jury trial. The baseball establishment, fearing a negative outcome, launched a war of words. Branch Rickey told a congressional committee that Gardella and others who opposed efforts to strengthen baseball’s antitrust exemption were persons of “avowed Communist tendencies”, and added, “Without the reserve clause,

baseball cannot endure.”[fn] Stephen Miller, “Danny Gardella, 85, N.Y. Giant,” New York Sun, March 10, 2005.[/fn] Many journalists shared this opinion. According to author Ron Briley, “Dan Daniel asserted that abolishing the reserve clause would bring chaos, while Shirley Povich of the Washington Post insisted that players were “delighted with the high salaries paid by MLB and wanted no government interferencewith the game.”[fn] Ron Briley, “Danny Gardella and Baseball’s Reserve Clause: A Working-Class Stiff Blacklisted in Cold War America,” Nine, Fall 2010.[/fn]

Sensing that the owners’ cause was doomed, on June 5, 1949, Chandler allowed the jumpers to return to the major leagues in return for dropping their litigation. Lanier and Martin complied, but Gardella refused. Johnson, Gardella’s lawyer, questioned Chandler in a pretrial deposition on September 19, and got him to concede that baseball earned $750,000 from radio rights and $65,000 from television. After a second day of questioning, a defensive Chandler and other baseball officials approached Johnson and Gardella with a proposed settlement. On October 8 the owners announced that the case had been settled; Gardella dropped his suit in exchange for a cash payment. The amount was not announced, but in November 1951 Gardella said it was $60,000, half of which went to his lawyer. At the time, Gardella was employed as a $36-a-week hospital orderly in Mount Vernon, New York. Upon receipt of the money, he bought a house in Yonkers so his growing family could move out of his father-in-law’s home. He was reinstated to the Giants on November 3, 1949, and released to the St. Louis Cardinals the same day.

Gardella’s hope for a continued major-league career ended abruptly. After one pinch-hitting appearance, the Cardinals sent him to the Texas League’s Houston Buffaloes, where he played in 39 games, batting .211 with two homers; he was placed on Houston’s inactive list on June 15. During Gardella’s stay, team president Allen Russell sometimes recruited him to sing to the fans before games. In August he was picked up by brother Al, manager of Bangor (Pennsylvania) of the North Atlantic League, where he hit .337 in 26 games.

In mid-October, Gardella announced, “No more baseball for me—from now on I’m a singer,”[fn] “Gardella Opens Singing Career Here; Is Through With Baseball, He Says,” Gloversville (New York) Morning Herald, October 14, 1950, 7.[/fn] and signed to tour the vaudeville circuit, singing songs from Broadway shows. He would start in Gloversville, New York. If all went well, he planned make a career of it. It didn’t go well; Gardella later claimed that someone associated with Organized Baseball tried to block his entertainment career.

Gardella signed with Brooklyn’s semipro Bushwicks in April 1951. In mid-May, his brother Al, now manager of Three Rivers (Provincial League), signed him as an outfielder/first baseman. After hitting .178 in 42 games, he was released by new manager Del Bissonette. It was Gardella’s last stop in Organized Baseball. Gardella had a number of occupations during his post-baseball career. After his release by Three Rivers he joined the athletic staff at the Concord Hotel in Kiamesha Lake, New York. In 1952 he was a drill press operator for the Otis Elevator Company. Gardella was reported to be broke after his New York restaurant failed in 1955. After a stint on a construction project, he worked as a warehouseman for Western Electric for more than two decades.

Gardella’s family grew to ten children, three boys and seven girls. Later in life, as baseball’s free-agency era began, he was frequently interviewed by sportswriters about his fight with baseball. “If I didn’t sue, they would have destroyed my spirit,” he told the New York Daily News in 1994. “In some ways, I considered the settlement a sellout, a moral defeat. I think they would have lost if the case went all the way to the Supreme Court. … But my lawyer told me they would delay it for years, and still find a way to keep me out of the game. I loved playing for the Giants. They were my home team. I still feel as though I beat them.”[fn] Jim Callaghan, “Baseball Rebel: Ex-Giant Took On Owners in ’40s,” New York Daily News, September 18, 1994[/fn]

One Mets game per year satisfied Gardella’s need to watch live baseball; his primary sports interest in 1966 was watching pro football on television. During the 1960s he became friends with newspaper columnist Maury Allen; they would often jog ten miles, sometimes stopping to discuss old tales of the game. In May 1975, still focused on physical fitness, Gardella ran in the Yonkers Marathon. Katherine Gardella died on August 30, 2004. Danny followed her six months later, on March 6, 2005, when he died of congestive heart failure at a hospice in Yonkers, New York. He was 85 years old. His ten children and 27 grandchildren survived him. He is buried at Mt. Hope Cemetery, Hastings-on-Hudson, New York. In Maury Allen’s view, “The baseball establishment didn’t make much of a fuss over Gardella when he left us. But remember this. He led the league in laughter in his time. That’s Hall of Fame stuff in my book.” [fn] Maury Allen, “Danny Gardella: Baseball’s King of Laughter,” thecolumnists.com/allen/allen68.html [/fn]

This biography originally appeared in “Van Lingle Mungo: The Man, The Song, The Players” (SABR, 2014), edited by Bill Nowlin.

Full Name

Daniel Lewis Gardella

Born

February 26, 1920 at New York, NY (USA)

Died

March 6, 2005 at Yonkers, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.