Dave DeBusschere

His induction into the Basketball Hall of Fame in 1983, not to mention his inclusion in 1996 on the list of the 50 greatest players in National Basketball Association history, is clear evidence that Dave DeBusschere did not err in choosing basketball over baseball in 1964. At the same time, the 1963 decision by the White Sox to protect DeBusschere over Denny McLain early in what would prove to be DeBusschere’s short baseball career, is a topic for debates about what might have been for the hard-throwing right-hander. That is because DeBusschere’s performances in three years of professional baseball offered tantalizing glimpses of pitching talent that clearly had major-league potential. In the end, the Detroit native left baseball observers guessing as he took his blue-collar work ethic to the hardwood, where his consistent all-star-quality performances made him a central cog on two New York Knicks NBA championship teams.

His induction into the Basketball Hall of Fame in 1983, not to mention his inclusion in 1996 on the list of the 50 greatest players in National Basketball Association history, is clear evidence that Dave DeBusschere did not err in choosing basketball over baseball in 1964. At the same time, the 1963 decision by the White Sox to protect DeBusschere over Denny McLain early in what would prove to be DeBusschere’s short baseball career, is a topic for debates about what might have been for the hard-throwing right-hander. That is because DeBusschere’s performances in three years of professional baseball offered tantalizing glimpses of pitching talent that clearly had major-league potential. In the end, the Detroit native left baseball observers guessing as he took his blue-collar work ethic to the hardwood, where his consistent all-star-quality performances made him a central cog on two New York Knicks NBA championship teams.

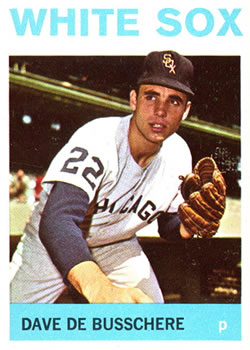

Born on October 16, 1940, in Detroit, DeBusschere became a hometown schoolboy legend, leading both the basketball and baseball teams at Austin Catholic High School to championships. Only three years after the basketball team was formed, he led it to a state title. The championship game featured a legendary match-up with another future NBA all-star, Chet Walker. DeBusschere also pitched the baseball team to the city title. Beyond the school yard the tall right-hander pitched a local team to a national junior baseball crown. Highly recruited by major colleges, he opted to stay home and attend the University of Detroit. There, DeBusschere led the hoop squad to its first postseason appearances, the National Invitational Tournament in his sophomore and junior years (1960 and 1961), and a berth in the 1962 NCAA tourney in his senior year. In the process DeBusschere earned numerous accolades that included All-American recognition as a sophomore, junior, and senior. On the diamond DeBusschere earned All-American honors as a pitcher, leading the Titans baseball squad to three NCAA appearances. He was sought after by both major-league baseball and the NBA, but the hometown Tigers were unwilling to allow him to also play pro basketball (he had been drafted by the Detroit Pistons) and he signed with the Chicago White Sox, getting a $75,000 signing bonus.

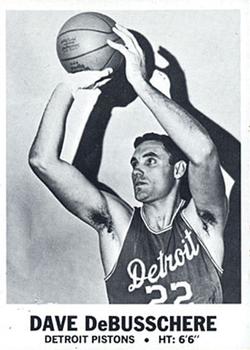

DeBusschere’s professional careers got off to fast starts in 1962. Pitching for the Single-A Savannah/Lynchburg White Sox in the South Atlantic League (the team changed home cities in August because of racial unrest), the 21-year-old right-hander compiled a 10-1 record. Starting 14 games and completing seven, DeBusschere had an earned-run average of 2.49 and struck out 93 in 94 innings. That performance earned him a call-up by the White Sox. In total, he pitched 18 innings in 12 games with no decisions and an ERA of 2.00 with the big league club. From there he went to the NBA, where as a forward he averaged 12.7 points and 8.7 rebounds per game for a Pistons team that made the NBA playoffs. There DeBusschere really shined, averaging 20.0 points and 15.8 rebounds though the Pistons were eliminated by the St. Louis Hawks in the first round. The versatile 6-foot-6 forward’s impressive play earned him a spot on the NBA all-rookie team.

Barely missing a beat, DeBusschere returned to baseball in 1963, and pitched the entire year with the White Sox, finishing 3-4 with a 3.09 ERA. DeBusschere’s second year (1963-64) with the Pistons was far less successful as injuries limited him to only 15 games. The Pistons also struggled, finishing 23-59 and missing the playoffs. In 1964 he was assigned to the White Sox’ Triple-A club in Indianapolis. where he won 15 games and lost eight, tying for third in the league in wins and posting an ERA of 3.93. The hard-throwing right-hander seemed to be coming into his own, validating the 1963 scouting report that called him “big and strong with fireball and better than average curve,” and adding, “Once he gets control he will be a real good pitcher. An all-sports star with lots of poise.” Not surprisingly, by this time both the White Sox and the Pistons were putting increasing pressure on DeBusschere to drop one sport and concentrate on the other, with each believing that his considerable potential would never be reached as long as his focus was split.

Things came to a head in November 1964. Seeking — so some believed — to get DeBusschere to commit fully to basketball, or maybe just seeking a spark for the Pistons, team owner Fred Zollner named him player-coach. Still, DeBusschere continued his baseball career. In the spring of 1964, baseball-healthy and ready for a promotion, he was instead sent back to Triple-A Indianapolis. DeBusschere had another strong year, again winning 15 games and though he lost 12, he lowered his ERA to 3.65.

But in view of his assumption of additional basketball responsibilities DeBusschere finally decided to leave baseball behind in September 1965. A looming NBA preseason led him to turn down another late-season call-up by the White Sox, making the 1965 season with Indianapolis his last in professional baseball.

While his accomplishments in the NBA validated his choice, DeBusschere’s brief baseball career still left open the question of what might have been if he had stayed in baseball. His major-league record of 3-4 with an ERA of 2.90 in 36 games and 102 1/3 innings pitched does not offer any definitive evidence, but his performance at all levels certainly indicated that he had promise. No less telling is that in 1963, when a ruling by Commissioner Ford Frick prevented the Sox from optioning bonus player DeBusschere to the minors, a move that would have allowed them to keep a young Denny McLain on the roster, they instead protected DeBusschere, believing that while control remained an issue, his curve and fastball made him a better, or at least more developed, prospect than McLain, who had yet to develop the curve that would later help him win 31 games in 1968 and Cy Young Awards in 1968 and 1969.

And yet it is hard to second guess DeBusschere’s decision given his subsequent basketball career. The effort to serve as player-coach proved an ill-fated experiment that was abandoned late in the 1966-67 season when he was replaced by Donnie Butcher. While DeBusschere finished with a coaching record of 79-143 and no playoff appearances, once he was able to turn his full attention back to his own play he quickly established himself as one of the NBA’s premier forwards. Still, while his own stature and reputation only increased, the remaining years in Detroit were frustrating as the team struggled, making the playoffs only in the 1967-68 season. Fortunately for DeBusschere, on December 18, 1968, he was given a new lease on life when the Pistons traded him to the New York Knicks for guard Butch Komives and center Walt Bellamy. Long coveted by Knicks management, which greatly appreciated his hard-nosed defense and heady play, DeBusschere proved to be the final piece in a puzzle that built what was arguably one of the finest pure teams in NBA history. His arrival in New York allowed Willis Reed to return to center, while DeBusschere was paired with Bill Bradley at the forwards. With the guard spots manned by Dick Barnett and Walt Frazier, the Knicks, coached by defensive guru Red Holtzman, played a game characterized by moving without the ball and hitting the open man. That offensive approach coupled with tenacious defense and tough rebounding made the Knicks a major force in the NBA that was emerging in the aftermath of Celtics great Bill Russell’s retirement.

And yet it is hard to second guess DeBusschere’s decision given his subsequent basketball career. The effort to serve as player-coach proved an ill-fated experiment that was abandoned late in the 1966-67 season when he was replaced by Donnie Butcher. While DeBusschere finished with a coaching record of 79-143 and no playoff appearances, once he was able to turn his full attention back to his own play he quickly established himself as one of the NBA’s premier forwards. Still, while his own stature and reputation only increased, the remaining years in Detroit were frustrating as the team struggled, making the playoffs only in the 1967-68 season. Fortunately for DeBusschere, on December 18, 1968, he was given a new lease on life when the Pistons traded him to the New York Knicks for guard Butch Komives and center Walt Bellamy. Long coveted by Knicks management, which greatly appreciated his hard-nosed defense and heady play, DeBusschere proved to be the final piece in a puzzle that built what was arguably one of the finest pure teams in NBA history. His arrival in New York allowed Willis Reed to return to center, while DeBusschere was paired with Bill Bradley at the forwards. With the guard spots manned by Dick Barnett and Walt Frazier, the Knicks, coached by defensive guru Red Holtzman, played a game characterized by moving without the ball and hitting the open man. That offensive approach coupled with tenacious defense and tough rebounding made the Knicks a major force in the NBA that was emerging in the aftermath of Celtics great Bill Russell’s retirement.

While the Celtics were able to defeat the Knicks in the Eastern Conference finals en route to their final championship of the Russell era, the 1969-70 season was a different story. With all the pieces in place from the beginning of the season, the Knicks started fast, winning 23 of their first 24 games, including what was then a league record 18 consecutive victories. With DeBusschere setting the tone on defense, while also averaging 14.6 points and 10 rebounds per game, the Knicks completed the regular season with a record of 60-22 and eliminated the Milwaukee Bucks to win the Eastern Conference championship. In a seven game playoff series that is remembered as much for the injured Willis Reed’s heroic final-game appearance as for anything else, DeBusschere’s all-around play and his inspired defensive effort on Wilt Chamberlain in the crucial fifth game were central to the New York victory. DeBusschere later offered an insightful look at that special season in his book The Open Man: A Championship Diary of the N.Y. Knicks, published in 1970.

The Knicks failed to retain their title the following season. Although they finished first in the Atlantic Conference with a 52-30 regular-season record, they lost the conference finals to the Baltimore Bullets in seven games. DeBusschere had another stellar season, being selected for the All-Star Game and the league’s all-defensive team while averaging 15.6 points per game. In 1971-72 they finished second in the Atlantic Conference and returned to the championship round, but were defeated by the Los Angeles Lakers, who won their first championship since moving to the West Coast from Minneapolis. DeBusschere again earned a spot in the NBA’s All-Star Game as well as on the league’s all-defensive team, on which he was becoming a fixture. Averaging 15.4 points and 11.3 rebounds per game, he continued to be a model of excellence and consistency.

Not satisfied with their close call in 1972, the Knicks opened the 1972-73 season intent on winning another world championship. With essentially the same team as the 1970 championship squad but with the additions of Earl Monroe, who replaced the retired Dick Barnett, and former Cincinnati Royals All-Star Jerry Lucas, who added depth at both center and forward, the team posted a 57-25 regular-season record before dispatching the Baltimore Bullets and the revived Boston Celtics to win the Eastern Conference crown. The finals were almost anticlimactic as the Knicks rolled over the Lakers in five games to win their second NBA title.

The 1973-74 season proved to be DeBusschere’s last; he decided to retire at the end of the campaign. Although the Knicks remained one of the league’s premier franchises, finishing second in the Atlantic Division before losing to the Celtics in the Eastern Conference finals, a physically weary DeBusschere decided to retire while still the embodiment of tough defense and team play. After 12 years he was still one of the league’s premier defenders, being selected again for the All-Star Game and being named to the all-defensive team. However, the grind that had begun right out of college with the double duty of baseball and basketball had worn him down and he elected to leave the game behind while still playing at a level he could be proud of, and before the core of the teams that had given New York two championships dispersed. DeBusschere went out on a high note, averaging 18.1 points per game, the second highest of his career, and 10.7 rebounds per game.

For his NBA career the Detroit native averaged 16.1 points and 11.0 rebounds per game. He had played in eight NBA All-Star Games and was a critical cog in the Knicks’ only two NBA championship teams. Further honors came in the years after his retirement. In 1983, along with roommate and teammate Bill Bradley, he became a member of the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame. In 1996 the NBA, celebrating its 50th anniversary, selected him as one of the league’s 50 greatest players.

At first DeBusschere was able to spend more time with his family, — his wife, Geri, and their three children, Peter, Michelle, and Dennis – in Garden City, New York, on Long Island, where the family had lived during his years with the Knicks. But he quickly stepped back into the basketball ranks. Not surprisingly, after his earlier coaching stint with the Pistons, he expressed no interest in that role, but he ran the New York Nets of the new American Basketball Association as general manager in 1974-1975, and in May 1975 he became commissioner of the ABA. He played an important role in bringing about the league’s merger with the NBA after the 1975-76 season. Lingering resentment of DeBusschere’s involvement with the ABA was thought to have delayed the retirement of his number by the Knicks until 1981. After that DeBusschere “came home” in 1982, becoming director of basketball operations for the Knicks, a job he held until 1986. In that position, after winning the first draft lottery, he chose Georgetown star Patrick Ewing, who would anchor Knicks teams for the next decade as they sought to bring home a championship trophy to add to the ones won by the teams on which DeBusschere had played such a critical role. DeBusschere also spent time as vice president for corporate development at Williamson, Pickett and Gross, a New York real-estate firm.

The man whose dedication to team play and tenacious defense always said as much about his heart as it did about his considerable athleticism was the victim of a heart attack. He collapsed on the street in New York City and died on May 14, 2003. He was 62 years old.

Last revised: April 10, 2022 (zp)

Sources

——. “1960s Rookie Scouting Reports on Former Players,” Baseball Digest, July 2000.

Addy, Steve (updated by Jeffrey F. Karzen). The Detroit Pistons: More than Four Decades of

Motor City Memories. Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing LLC, 2002.

DeBusschere, Dave (Paul D. Zimmerman and Dick Schaap, eds.). The Open Man: A Championship Diary of the N.Y. Knicks. New York: Random House, 1970.

Goldstein, Richard. “Dave DeBusschere, 62, Forward on Knicks’ Championship Teams Dies.”

New York Times, May 15, 2003.

Full Name

David Albert DeBusschere

Born

October 16, 1940 at Detroit, MI (USA)

Died

May 14, 2003 at New York, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.