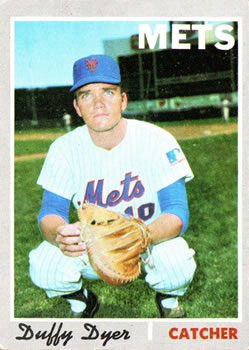

Duffy Dyer

In the sitcom Cheers, guys came in to have a cold one, talk about whatever was going on, and—most emphatically—defend Sam Malone. Malone, played by Ted Danson, was a washed-up pitcher for the Boston Red Sox turned owner and bartender of Cheers. Judging by the stories patrons would tell about his mediocre career, you would have thought he was Walter Johnson. If a stranger walked in off the streets and said anything negative about Malone’s career, the customers would unite to defend him.

In the sitcom Cheers, guys came in to have a cold one, talk about whatever was going on, and—most emphatically—defend Sam Malone. Malone, played by Ted Danson, was a washed-up pitcher for the Boston Red Sox turned owner and bartender of Cheers. Judging by the stories patrons would tell about his mediocre career, you would have thought he was Walter Johnson. If a stranger walked in off the streets and said anything negative about Malone’s career, the customers would unite to defend him.

Backin 1969 there was such a place—Donovan’s, an Irish Pub in Woodside-Jackson Heights area of Queens. This was Duffy Dyer country. Duffy was a light-hitting, good-fielding catcher who played with the New York Mets for half of his major-league career. He became a fan favorite on Opening Day of the 1969 season by belting a pinch-hit, three-run homer. Donovan’s became the home for Dyer fans to gather.

“We haven’t had a fight in here in a long, long time,” the bartender at Donovan’s said. “But if somebody puts the knock on Duffy in here, look out.”1

Don Robert Dyer, nicknamed Duffy, was born in Dayton, Ohio, August 15, 1945. His family was of Irish-English-Dutch stock. There was an old radio show called Duffy’s Tavern and the family would sit around and listen to it every week. Duffy’s mom was quite pregnant and laughing very hard at a joke on Duffy’s Tavern. Suddenly, she fainted. When she came to, she was in the recovery room of the maternity ward, and still in the twilight zone.

“How’s Duffy?” said Mrs. Dyer faintly.

“Oh, he’s doing just fine,” said one of the nurses, who was, of course, accustomed to such mutterings. The nurses started calling the infant boy “Duffy,” and so did Mrs. Dyer.2

His father, William E. Dyer, moved the family to Arizona and Duffy blossomed as one of the state’s top ballplayers. He played baseball, basketball, and football at Cortez High School in Phoenix. He helped lead his team to the state Class-AA championship in his senior year in 1963. He was named to All-City and All-State teams. He also received honorable mention on the All-Arizona prep football team at quarterback. It was then on to Arizona State to play for the Sun Devils.

The 1965 season was one to remember for Dyer and his Arizona State teammates. It was also the start of a continuous trek for the Sun Devils to the NCAA tournament. Dyer batted .325, four home runs, 38 RBIs, and 15 stolen bases in leading the Arizona State to the Western Athletic Conference championship. Also on that team were Rick Monday, Sal Bando, and a freshman not yet eligible to play on the varsity named Reggie Jackson.

Arizona State won the NCAA District Seven in two games over Colorado State and Dyer was named to the All-Conference team. The Sun Devils steamrolled to their first NCAA title in 1965, beating Ohio State in the championship game, 2-1. In the first three games of the College World Series, the Sun Devils won by a combined score of 36-8. Dyer went 3-for-6 with a two-run homer in their 13-3 rout of St. Louis. He played mostly in the outfield and it wasn’t until 1966 that he became full-time catcher.

At the end of season he was drafted by the Milwaukee Braves, but Dyer decided to stay in school and play in a summer league called the Basin League. The Basin League was established in 1953 with seven teams from South Dakota (Mitchell, Watertown, Winner, Chamberlain, Yankton, Huron, and Pierre), and one from Nebraska (Valentine). It was a league using former professional players with a mix of amateurs. The name “Basin” came from the geographical fact that a number of teams were situated in cities along the Missouri River Basin. It was a league where players could retain their amateur status yet scouts would still come to have a look. In later years when the Basin League became just a summer college league, it was touted as the finest in America. Dyer played for the Valentine Hearts in the summer of 1965, before returning for his junior season at Arizona State. He batted .237 in 50 games for Valentine.

In 1966 at ASU, he hit .326 with 10 triples and batted in 32 runs. He was named to the All-Conference First Team and The Sporting News College All-American Second Team. He tied for second on the all-time Sun Devils consecutive hits list with eight. He would later be inducted into the ASU Hall of Fame.

The New York Mets drafted him with their first pick in the June 1966 secondary phase of the free agent draft. Signed by Bob Scheffing and Dee Fondy, Dyer was sent to Williamsport of the Eastern League. There in 22 games he hit a sparse .173 with only two extra-base hits. He was then moved down to Greenville in the Western Carolinas League. He was able to get back on track a little, hitting .246 in 19 games.

Dyer was back at Williamsport in 1967, playing in 106 games. He still was having a hard time adjusting to the league, batting only .194. On June 22, 1967, he “almost” hit his first home run as a pro. With the bases loaded he hit a pitch by York’s Rupe Toppin over the left-field wall, but the runner on first base held up until the ball cleared the fence and Dyer passed him and was called out. As a result he got credit for a single, but did get three RBIs in Williamsport’s 4-2 victory.

He moved on to Jacksonville of the International league for the 1968 season. There he found his power with 16 home runs and 43 RBIs for the season. His batting average was still just .230, but his defense and his power earned him a spot in the International League All-Star Game. He was called up to New York with three weeks left in the season. He played in just one game, starting and catching Dick Selma in a 4-3 loss to the Phillies. Dyer was l-for-3 with a single off Chris Short.

While, of course, 1969 was a very special season for the Mets and for Dyer, the rookie almost didn’t get a chance to be a member of that world championship team. On March 29, 1969, a report in The Sporting News claimed that Paul Richards, vice president of the Braves sought a package of pitcher Nolan Ryan, infielder Bob Heise, first baseman Ed Kranepool, and either catcher J.C. Martin or Duffy Dyer, for Joe Torre and Bob Aspromonte.3 Instead Richards traded Torre to the Cardinals. Dyer made the Mets out of spring training as the third-string catcher to Jerry Grote (Martin was the backup).

“Dyer proved himself a good defensive catcher at Jacksonville last year and capable of hitting home runs,” Mets manager Gil Hodges said. “Found him to be a good steady receiver in intersquad and exhibition games, and decided to keep him.”3

Dyer had a flair for the dramatic right from the start. On Opening Day he got a call from Hodges to come out of the bullpen and pinch hit in the bottom of the ninth with the Mets trailing Montreal, 11-7.

“I remember distinctly that my knees were shaking while I was at bat. As soon as I hit the ball I knew it was a home run but I started sprinting to first and I was still sprinting halfway to second. Then I realized the ball was gone and I slowed down, and when I touched second base I remember saying to myself, My God, I hit a home run in the major leagues.”4

His pinch-hit single on May 30 gave the Mets a 4-3 win over the Giants. He was optioned to Tidewater on July 3 because the minor league club was out of catchers. He compiled a .313 average with five homers and 26 RBIs in 35 games for Tidewater. A little more than a month later he was back in the fold in New York and providing late-game heroics again. In the first game of a doubleheader on August 17, he hit a three-run homer off San Diego’s Joe Niekro to spark a 3-2 win.

In the World Series he only had one pinch-hitting opportunity and grounded out to shortstop Mark Belanger. Dyer ended the year hitting .257 with three homers and 12 RBIs in 29 games for the ’69 Mets, but he got a world championship ring as a rookie. It turned out to be his only one in 14 seasons in the majors.

He remained behind Jerry Grote in New York, but the durable, hardy, and aggressive Dyer gave the Mets assurance at that vital position when Grote needed a rest or was injured. After J.C. Martin was traded in spring training in 1970, Dyer moved up to second string and wound up getting into 59 games, hitting .209 with two homers. In 1971 he again played in 59 games and hit a little higher at .231. Perhaps his best game that year happened on May 29, when he hit two doubles and a triple while calling signals for the young Nolan Ryan in a 2-1 victory over San Diego. Ryan fanned 16 Padres as the Mets swept a doubleheader.

The 1972 season was arguably Dyer’s best as a pro. Grote’s continuing health problems allowed Dyer to take full advantage of his opportunity. He played in a career-high 94 games—starting 91 behind the plate—and also reaching career bests with eight homers and 36 RBIs. He led the National League catchers with 12 double plays and threw out the majority of runners that tried to steal (40 of 79). He won National League Player of the Week June 12-18 and was playing so well that even after Grote came back, manager Yogi Berra decided to stay with Dyer. His improvement with the bat can be traced back to his fall session in Florida with the former home run champ and Mets broadcaster Ralph Kiner.

“I’d like to think I helped him,” said Kiner modestly, “but he’s the guy doing the job.”5

Dyer began the season on fire and after a four-hit game on May 17, he was hitting at .533. He batted .300 until the final week of June.

Dyer almost caught his first no-hitter in the opening game of a July 4 doubleheader against San Diego. Tom Seaver was pitching and had one out in the ninth when Leron Lee broke his bat on a low inside pitch and looped into center field. Duffy was more upset by the hit than Seaver. He picked up Lee’s bat after the hit and threw it aside in disgust. Later in the dugout, he angrily ripped off his catching gear and threw it around.

“I was all psyched up for a no-hitter,” the usually quiet receiver admitted. “I wouldn’t have been so mad if he hit a home run. But it was the right pitch and Tom threw it in the right spot.”6

Yogi explained it all very simply why Dyer, who labored in Grote’s shadow for three years was playing instead of Grote. “He worked hard to improve himself and he did,” Berra declared. “And he gives us more of a threat with the long ball.”7

Dyer’s offseason hobby was somewhat unusual for a ballplayer. He made flower arrangements at a show called “Artistry in Flowers” at the Mall at Roosevelt Field. In a demonstration, Dyer created a little bouquet of white and red carnations. Dyer first became entranced with bouquets as a boy in Phoenix. “I used to watch florists and marvel at how they put together such intricate designs,” he explained.8

Over the next two years he went back to his role as the second-string catcher behind Grote, who was finally healthy and had won his job back. Dyer was almost traded, as there was interest from the California Angels with his former coach at Arizona State, Bobby Winkles, as the manager in Anaheim. Over those two years (1973-74), Duffy only hit one homer and barely kept his average above the .200 mark.

Still, Dyer made key contributions. The biggest came on the night of September 20, 1973. The Mets, who had been in last place a month earlier, found themselves 1½ games behind the Pirates at Shea Stadium, but they were down to their last out. Dyer’s pinch-hit double off lefty Ramon Hernandez tied the game in the ninth inning. The eventual NL champion Mets went on to win in 13 innings thanks to a wild ricochet in what became known as the “Ball on the “Wall Game.” That was, however, Dyer’s last at-bat of the year and he finished with his lowest batting average as a Met at .185.

After hitting .211 in 63 games the following year, he was traded to the Pirates for outfielder Gene Clines on October 22, 1974. Dyer served as the primary backup for Manny Sanguillen, but in spring training he found himself playing some games at first and third base along with his catching duties. Pirates manager Danny Murtaugh had plans for Dyer.

“I’m looking for Dyer to give Sanguillen some relief behind the plate,” Murtaugh said. “Manny was in 151 games last year and I think it would be better for him and the team if he got some more time off. I’ve seen enough of Dyer to think he can hit better than he did last year.”9

Ex-Met Dyer came back to haunt his former teammates with a game-winning homer off Bob Apodaca leading off the 15th inning on August 3. The doubleheader sweep, with Dyer playing in both games, helped the Pirates retain their lead in the NL East. He walked with the bases loaded to bring in a run in his only postseason appearance that fall, as the Bucs were swept by the Reds in the NLCS.

Over the 1975 and ’76 seasons, Dyer served as more than adequate in his backup role. The highlight of the 1976 season was catching a no-hitter by John Candelaria. “He didn’t have his real good velocity,” said Dyer, “but his fastball was moving well. The big thing was that he was keeping the ball down. He’s usually a highball pitcher. But tonight he kept it down.” Dyer’s got almost as much a kick out of the no-hitter as Candelaria. “You always dream of catching a no-hitter,” he said. “This is one of my biggest thrills.”10

The trade of Sanguillen to the A’s for manager Chuck Tanner would open the door for Dyer to claim the starting spot in 1977. Tanner praised Duffy’s handling of the pitchers. “He is a good example of a player who shouldn’t be judged by statistics. He is a plus man on any club.”4 Coming out of spring training, Tanner was stressing defense and gave the starting job to Dyer over Ed Ott.

Dyer had his second-best season hitting the ball. In 270 at-bats, he hit 11 doubles, three homers, and 19 RBIs to go with a .241 average. Dyer was like a coach on the field and was frequently asked for his thoughts when it came to the pitchers. Dyer had a knack of being able to tell when a pitcher was losing his stuff. In one game, Dyer told Tanner that left-hander Terry Forster had outstanding stuff. Forster appeared to be a stopgap reliever, brought in to face a few left-handed hitters against the Mets. When it came time for Mike Vail, Dave Kingman, and Joe Torre, all righty hitters, Tanner figured to go with a right-handed ace reliever, Rich Gossage. He stuck with Forster, who struck out Vail and Kingman and nailed Torre on a soft comebacker.

Dyer was sometimes compared to the old Indians catcher, Jim Hegan, for his defensive ability. In 545 total chances during the 1977 season, Dyer made only two errors. He wound up with a .992 career fielding percentage and made only 30 errors during 14 years in the big leagues. The 1978 season, in which he slumped to .211 in 58 games, was his last for the Pirates. Pittsburgh released him in November. He signed a three-year deal with the Montreal Expos to be the backup to Gary Carter. He served as a quality role player, hitting .243 in just 74 at-bats. He was traded during spring training in 1980 to the Detroit Tigers for future Mets manager Jerry Manuel. This was Dyer’s last stop as a player; 1980 was his last year as a productive backup catcher with four homers and 11 RBIs. He ended his playing career with 30 home runs, 173 RBIs, and a .221 average. This would not be the end of his baseball career. Not by a long shot.

Dyer was back in baseball in 1983 as the bullpen coach for the Chicago Cubs. The following two years he would be the manager of Kenosha of the Midwest League, an affiliate of the Minnesota Twins. His first year the team went 70-68. His club went 79-60 and won the league championship in 1985. Dyer was named Manager of the Year. Then it was onto Double-A El Paso in the Brewers organization and another championship in 1986. El Paso also had its league’s best record, going 85-50. Looking to repeat in 1987, Dyer led his team to a 75-59 record and another playoff appearance. He was also named for the second time in three years Manager of the Year. The Brewers moved him up to manage Triple-A affiliate Denver. They would go 72-69.

The Brewers were very impressed with Dyer’s ability to manage, but decided they wanted him up on the major league club to be the third base coach. He held that position in Milwaukee for the next seven years. He moved over to the Oakland A’s as a coach from 1996 to 1998. Dyer really wanted to manage again and got that opportunity for the Orioles to take over Bluefield in the Rookie League. He experienced his first losing season, going 25-43. The next year his team of mostly first-year players posted a 31-32 record. Dyer was a very hands-on manager and considered by many to be a good teacher.

The independent Bridgeport Bluefish of the Atlantic League hired him for the 2001 and 2002 seasons. He led the Bluefish to a playoff appearance in his second season. After almost three decades, Dyer returned to the Mets as a scout in 2003 and 2004. He went back to the field as manager of the Erie SeaWolves in 2005 and 2006. Dyer was named minor league catching coordinator of the San Diego Padres in 2008. He was hired in 2014 to manage the Kenosha Kingfish of the Northwoods League, a collegiate developmental league. His son, Brian, served as hitting coach for the Wisconsin club.

Besides Brian, Duffy and his wife, Lynn, have three grown children: Cami, Megan, and Kevin. The Dyers reside in Phoenix during the offseason.

Dyer’s managers during his career were some of the best in the game: Gil Hodges, Yogi Berra, Danny Murtaugh, Chuck Tanner, Dick Williams, and Sparky Anderson. He was a player that every club needs: a quality person willing to accept his place on the team and work hard at all times. He was the prototypical bench player and could be counted on for contributions off the bench and when called on to start. So if you ever go into Donovan’s, remember to have a beverage for old Duffy.

Since 2014, Dyer managed the Kenosha Kingfish, a summer collegiate club in the Northwoods League. His son Brian is the team’s hitting coach.

Last revised: July 1, 2021.

SOURCES

New York Daily News. Amazin’ Mets: The Miracle of 69 (Daily News Legends Series). Sports Publishing 1969

The Sporting News, 1966-1982

Sports Collectors Digest, January 23, 1998

www.attheplate.com/wcbl/basin_league

www.northwoodsleague.com/kenosha-kingfish/

Duffy Dyer player file; National Baseball Library (various clippings)

Arizona State Sun Devils Media Guide

NOTES

1 Unidentified newspaper clipping in Duffy Dyer’s Hall of Fame player file.

2 Stanley Cohen, A Magic Summer: The ’69 Mets (San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich Publishers, 1988), 170.

3 Unidentified newspaper clipping in Duffy Dyer’s Hall of Fame player file.

4 Cohen, 170.

5 Unidentified newspaper clipping in Duffy Dyer’s Hall of Fame player file.

6 Unidentified newspaper clipping in Duffy Dyer’s Hall of Fame player file.

7 Unidentified newspaper clipping in Duffy Dyer’s Hall of Fame player file.

8 Unidentified newspaper clipping in Duffy Dyer’s Hall of Fame player file.

9 Unidentified newspaper clipping in Duffy Dyer’s Hall of Fame player file.

10 Unidentified newspaper clipping in Duffy Dyer’s Hall of Fame player file.

Full Name

Don Robert Dyer

Born

August 15, 1945 at Dayton, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.