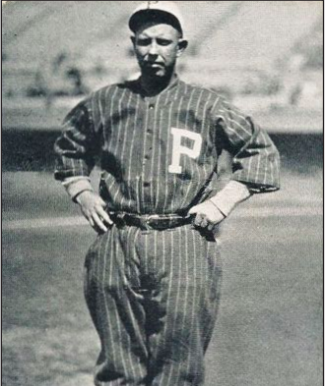

Duke Kenworthy

Before and after his two years in the major leagues, when he was one of the most successful batters for the Federal League’s Kansas City Packers, Bill Kenworthy was both a pitcher and second baseman. He led the Packers in slugging in both 1914 and 1915, and led the team in home runs and RBIs in the first of the two years. In back-to-back seasons in 1909 and 1910, he’d been a 20-game winner.

Before and after his two years in the major leagues, when he was one of the most successful batters for the Federal League’s Kansas City Packers, Bill Kenworthy was both a pitcher and second baseman. He led the Packers in slugging in both 1914 and 1915, and led the team in home runs and RBIs in the first of the two years. In back-to-back seasons in 1909 and 1910, he’d been a 20-game winner.

Kenworthy came from English/Irish background.1 His parents were Ohio farmers – Benjamin Franklin Kenworthy and Jennie (Lowry) Kenworthy. There appears to be something of a tradition of naming Kenworthys after political figures. Benjamin and Jennie named their son William Jennings Kenworthy, after William Jennings Bryan. Appropriately, he was born on the Fourth of July, 1886, on a farm near Hopewell, Ohio, in a Guernsey County community now called Indian Camp.2

Bill Kenworthy was the second of six children in the family at the time of the 1900 census, when the family lived in Knox, Ohio. He attended Hopewell Elementary School and Old Washington High School, Old Washington being another village in Guernsey County about midway between Zanesville and Wheeling, West Virginia. Kenworthy graduated from Muskingum College, with a teacher’s degree.

Kenworthy’s professional baseball career began in 1907, the year he turned 21, with Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania, and then, after that club folded, for the East Liverpool team in the Class-D Pennsylvania-Ohio-Maryland League.3 He’s listed as a pitcher, appearing in 24 games. No statistics are shown for his mound work but he is credited with 15 hits in 65 at-bats, for a .231 batting average. During his first six seasons, he taught grade school during the winter months.4

In 1908, Kenworthy was 17-14 pitching for the Zanesville Infants of the Class-B Central League. He’d been drafted by Toledo and farmed out to Zanesville. He hit .255 and had served as a utilityman playing a number of infield positions.5

Kenworthy’s next two seasons were his best as a pitcher. He was a right-hander, though a switch-hitter, but by no means intimidating in stature as a pitcher. He is listed as being 5-feet-7 and weighing 165 pounds. In fact, after Kenworthy’s passing in 1950, Chuck Dressen said of him, “He’s the first person I ever saw who put shot in the fingers of his glove. His hands were so small he added the weight so his fingers could close around the ball when it hit his palm.”6 His record proved convincing. He was 24-12 for Zanesville in 1909 and 22-17 for them in 1910. At the bat, he was ordinary at best: .246 and .229. Things changed in 1911.

At the close of the 1910 season, the Boston Red Sox drafted Kenworthy out of Zanesville. The Denver Grizzlies really wanted him, though, and in late October Denver manager Jack Hendricks made a trip to Boston and convinced Red Sox owner John I. Taylor that Kenworthy needed another year in the minors; he paid Taylor $1,000 to secure his services for the Grizzlies in 1911.7

Four teams had reportedly been in the bidding at the time of the draft. Clark Griffith of the Reds was said to have approached Denver during the 1911 season to try to get Kenworthy. He was 9-3 for Denver, listed as having pitched in 18 games. He played, in all, in 65 games, batting .315 despite playing at a higher level, in the Class-A Western League. The Denver Post declared him “the best utility man that ever played in the Western league.”8 The newspaper noted that his contract still belonged to Boston, and that he was making more money on his large Ohio farm than he was from baseball. He was enticed back, joining Denver for spring training in Hot Springs, Arkansas, and for a “little utility man” wielded a remarkably large baseball bat, a 42-inch “war club that he had made from a piece of timber from his farm near Cambridge,” one he had seasoned “behind the kitchen stove” all winter.9

Kenworthy had another excellent season in 1912. Judging from newspaper reports, he never knew for sure what position he was going to play from one day to the next but was game for anything. On August 18 it was reported that he had been sold to the Washington Senators for an amount though to be $3,000.10 He finished out the season for Denver, serving as the catcher in the final game of the season so he could leave for Washington having played at least once at every position.11

Kenworthy’s major-league debut was with the Senators at Washington’s Griffith Stadium on August 28, 1912. He played left field, batting sixth in the order, and was 1-for-4, his first major-league hit being a single off St. Louis Browns pitcher Jack Powell. The Browns won, 3-2. The next day the New York Yankees were in Washington and Kenworthy collected two singles and his first RBI off Ray Fisher; Washington won, 2-1. New York scored its lone run in the fourth. In the bottom of the seventh, Frank LaPorte doubled, took third on a wild pitch, and then easily scored when Kenworthy tied the game with a single to center field. Kenworthy stole second and scored the go-ahead run when George McBride also singled to center.

Kenworthy collected one or more hits in every one of his first six games, coming up short in his seventh game, when he was a pinch-hitter with just one fruitless at-bat.

At the end of his first brief foray into big-league baseball, Kenworthy was 9-for-38 (.237) with two RBIs. He had played left field in six games, right field in three, and during another game he had played both third base and right field.

The major-league season then over, Kenworthy was said to have reported back to Denver in time to play for the Grizzlies in the playoffs against the American Association champion Minneapolis Millers.12 Denver won the postseason series. Whether Kenworthy participated, we have not yet been able to determine.

At the end of November, Griffith “announced … that he cannot use Bill Kenworthy and says he will probably turn him back to Denver.”13 In December Washington sold his contract to Sacramento. The Washington Evening Star’s J. Ed Grillo was somewhat blistering in his appraisal of Kenworthy: “The dropping of this player does not come as a surprise to local patrons of the game. It was evident from the first day that he appeared in a Washington uniform that Kenworthy was never intended for a major league club.”14 Denver manager Hendricks, Grillo added, had touted Kenworthy as the next Ty Cobb.

There was already a minor controversy regarding Kenworthy that went to the National Commission to be resolved in January 1913. He claimed that in being released from Denver to Washington his salary had been increased 25 percent. He was looking to have the increase applied when he was released back to Denver. The commission disagreed, but he was awarded his fare from Des Moines to Denver.15

Kenworthy played for Sacramento in the Pacific Coast League in 1913, and had a very good year. He appeared in 177 games (the PCL had a very long schedule) and hit for a .297 batting average with 185 base hits.

In June news stories appeared that said that he was coming into a large inheritance. Apparently his “uncle Joshua Kenworthy, late of London … was burned to death in a hotel in Connecticut.”16 The Sacramento Bee (and other newspapers) reported the size of Joshua Kenworthy’s estate as $50 million. After division among the heirs, Bill Kenworthy was due to receive $1 million.17 In 2018 dollars, his share would be worth more than $25 million. It wasn’t going to get in the way of playing baseball, though, he said: “If I quit playing baseball, it will be because I have been benched. I like the game too well and the fun beating the other fellows has kind of got a barnacle hold on me.” The paper dubbed him “His Lordship,” a moniker the Los Angeles Times picked up in a September subhead: “‘His Lordship’ Helps Wolves to Two Wins.”18

Sporting Life reported that Joshua Kenworthy himself had inherited $30 million and by the time of his death, which happened while he was touring the United States, his fortune had increased to $50 million.19 It is unclear whether Bill Kenworthy ever received his share of the purported inheritance. (See below.)

On January 10, 1914, Kenworthy announced that he had received an offer to play in the Federal League – a three-year contract – and said, “I can get more money in three years in the Coast League than in five at my present salary.”20 He said he had notified manager Harry Wolverton of the offer and would not sign with the Federal League until he heard from him. Wolverton replied, “If he isn’t satisfied with the contract we offered him he can jump to the Federals or do anything else he wants.”21 On February 14 it was reported that Kenworthy had signed with the Kansas City Packers for a reported $2,000 bonus.22

By 1914 Kenworthy was often being called “Duke.” He played in almost every game – 146 of 151 – and hit for a .317 batting average, playing second base and leading the team in runs batted in with 91. His 15 homers were more than double anyone else on the team and just one behind Dutch Zwilling’s 16 for the league lead. He had two five-RBI days, but his biggest game was the first game of a June 13 doubleheader against the visiting Brooklyn Tip-Tops, when he drove in six runs in a 10-7 win with a two-run homer in the third inning and a go-ahead grand slam in the bottom of the eighth.

Kansas City finished in sixth place in the eight-team Federal League, 20 games behind Indianapolis.

In 1915 the Packers showed better, in fourth place but only 5½ games behind the Chicago Whales in a race where the top five teams all finished no more than six games from first. Kenworthy played second base again, but was used more sparingly, appearing in 122 games, while seeing his homers drop from 15 to 3 and his RBIs drop from 91 to 52. He had two four-RBI games, on June 15 and September 8. His batting average was .298 – first on the team. He was third in runs batted in. With the Federal League broken up, Kenworthy stands today as the franchise leader in several categories but that was not a distinction of great worth.

Under the terms of the February 1916 settlement with Organized Baseball, which effectively terminated the Federal League, the F.L. owners remained liable for any contracts they had signed, but were permitted to sell them.23

There was a year to run on Kenworthy’s three-year contract, though the league itself had folded. After the settlement, he met with Harry Wolverton, then the manager of the San Francisco Seals. Wolverton said he already had a second baseman, and noted that Kenworthy was still under contract for all of 1916 “which is rather prohibitive so far as the Pacific Coast League is concerned.”24 Wolverton’s meeting was not unfriendly, but the San Francisco Chronicle labeled Kenworthy as “Jumper Bill” in its subhead.

On March 3 Kenworthy signed a deal with manager Rowdy Elliott of the Oakland Oaks.25 He thus returned to the Pacific Coast League and spent almost the entire rest of his career there (the next nine seasons), beginning with the Oaks in 1916. Oakland apparently gave him a two-year deal “at a fancy figure” and, the Kansas City Star reported, “He’ll captain the team, too. Kenworthy is very popular on the coast.”26

Oakland played 208 regular-season games in 1916 and Kenworthy played in 200 of them, leading the PCL with a .314 batting average. The team finished in last place, a staggering 56 games out of first. In the Rule 5 draft on September 15, he was selected by the St. Louis Browns.

In 1917 Kenworthy returned to the major leagues for a final time, although only briefly. He appeared in five games for the Browns, the first as a pinch-hitter on April 15 and then four games at second base, the last two being in a doubleheader against the visiting White Sox on May 8. In 10 at-bats, he had one base hit, a single in the second game of the doubleheader. That was his last hit in the big leagues.

On May 13 manager Frank Chance of the Los Angeles Angels announced that he had purchased Kenworthy’s contract from St. Louis.27 The “Duke” played 142 games for the Angels, batting .302 (he had only one home run all year, matching his 1916 total). He pitched in one game and was 1-0.

In mid-August Kenworthy received his draft notice from the US Army and was asked to present himself for a physical. A growth over one of his eyes resulted in a temporary exemption from military service. He was to undergo care from an oculist and then report again in March 1918.28 He assisted the war effort by working at a shipyard in Oakland, “his patriotism having gained supremacy over his sporting blood.”29

Back with the Angels in 1919, “Lord Kenworthy” played third base at the beginning of the season, but then switched to second for most of the season. He was among the league leaders in sacrifice hits for most of the year, but perhaps lost something in terms of hitting. In late August, he was out of the lineup, batting just .218. The Sacramento Bee reported on September 12 that he had been released by the Angels that week. Three days later, Kenworthy was playing shortstop for Seattle. Season-end stats in the Seattle Daily Times show him batting a combined .227 for the Angels and the Seattle Purple Sox, having appeared in 146 games. He hit three home runs. After the PCL season, he played independent ball for the Sperry Flour Company in Stockton, California. He had not yet received any inheritance, and he kept playing baseball. Even during 1918, he had played ball for the shipyard team. In December he apparently had an eye operation. Money was tied to his name; the Seattle newspapers often called him “Kopecks” Kenworthy.30

Seattle became the Rainiers in 1920 and Kenworthy remained with the team for the next two years. He played under manager Clyde “Buzzy” Wares in 1920 (they had known each other since Zanesville) and enjoyed a full year of play at second base, clearly back in good form, playing in 180 games and hitting for a .313 average.

Wares and Kenworthy were friends and partners in a billiards business (a poolroom) in Hanford, California. Seattle offered Wares a significant raise from the year before, but Wares demanded $7,500, a sum at the time said to be greater than even some major-league managers got. He wouldn’t budge, but recommended Kenworthy to Seattle’s president, W.H. Klepper, who had come to Hanford to sign Wares. Kenworthy accepted the job for $5,600, a figure that Klepper released “to know that the club has not been stingy.” It was a salary said to be as large as any in the PCL, and larger than most. As part of the deal, Kenworthy moved to Seattle.31 In some previous offseasons, he had taught school but now he meant to devote his attention to the Rainiers.32

The Rainiers were in contention in both 1920 and 1921, finishing 5½ games out of first place in 1920 and 3½ games out in 1921. Kenworthy assigned himself to play second base again. He performed well on the field, but not without overcoming an injury during spring training at Pomona and extending himself. A 1921 midseason appraisal by the Seattle Daily Times: “Show us a better hitter, in the pinch or otherwise, than the old Iron Duke and we’ll buy. But the Duke has played many games on sheer nerve alone. He has been hurt this year than ever before and the day when Father Time beckons him to the bench naturally is drawn that much closer.”33 By season’s end he had appeared in 172 games and hit for a .343 average, a very successful year.

It was in 1921 that the local papers consistently referred to Kenworthy as the Duke, the Iron Duke, or the Duke of Kenworthy. The ballclub was increasingly referred to as the “Indians” in the Daily Times. As the season closed, he thanked the fans, and the ballclub’s directors for their support, letting it be known he was seeking a two-year contract to cover 1922 and 1923.34

The Seattle paper said he was getting better with age, and that there was “no better hustler, no quicker thinker, no better ballplayer in the minor leagues.”35

The same story declared that Kenworthy was “probably the best fixed ball player financially in the Pacific Coast League. He does not have to play baseball from a financial necessity. … He has made some investments which have been profitable.”36

As for the inheritance, it had still not arrived (and perhaps never did). The story was complex. There had been the British uncle who had perished in the hotel fire, a fire that may have been as much as 15 years earlier than originally understood. The American Kenworthys had not known there was a connection to any fortune and when the British government published a notice asking for heirs to come forward, none did. The $50 million was thus “escheated to the crown.” Fifteen million was used to build the Kenworthy Canal in Sheffield County. One of Bill Kenworthy’s American uncles was an attorney and in 1921 it was said he had brought a case in the English courts where it continued to be tangled up.37

J.R. Boldt, the majority stockholder, was slated to become president of the Seattle club on October 18. W.H. Klepper took an opportunity that presented itself and moved to purchase the Portland Beavers ballclub in 1921. Kenworthy left Seattle without having signed the two-year contract he was seeking.38 Word was that he wanted to join Klepper in Portland, and was seeking a substantial raise if he was to stay in Seattle. He said there was a clause in his contract that released him from any obligation to Seattle if he could not come to terms.39 On October 25 Klepper announced that Kenworthy would manage Portland.40

The announcement was premature. “Manager Deal in Air” was the headline in the November 6 Oregonian. Rumors began to circulate that the new skipper for the Beavers might be Bill Rodgers or Joe Devine. It was a bizarre situation that saw Kenworthy deny in early December that he had even been approached by Portland. He did, however, appeal to the national board of arbitration asking for his release from Seattle, citing the letter he had from Seattle that seemed to give him his freedom should he not come to agreement with the club. The board denied his appeal.41

Boldt was tired of waiting and on December 8 named Walter McCredie as manager of Seattle for 1922. This was not a surprise in and of itself, since for weeks it had been thought that McCredie might leave Portland for Seattle, and that Kenworthy would assume the post at Portland. On December 20 it was announced that Kenworthy had married, the “Duchess” being Arnette or “Nettie,” a longtime sweetheart from Oakland. Friends expressed surprise, having understood he was a confirmed bachelor. Kenworthy said he would like nothing more than to play for Seattle in 1922, that the city was his favorite city, but he also noted that he had tried to buy his way out of any obligation to the ballclub. Klepper said he’d given up thinking of Kenworthy as manager.42 Needless to say, it was all pretty confusing.

Kenworthy appealed the board’s decision to Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis. Klepper said he couldn’t wait any longer, and hired Thomas Turner as Portland manager.43 But things weren’t settled. A February 17 story in the Oregonian had Boldt, Klepper, and Kenworthy all huddling.44 The day before, Kenworthy said he had retired.

On February 18, 1922, Commissioner Landis suspended Kenworthy from baseball, placing him on the “ineligible list for refusing to furnish evidence in respect to a matter under consideration.” Said evidence was the letter he claimed he had that would grant him his release from Seattle. Such a letter, if it existed, could be considered a “secret agreement” which itself would contravene baseball’s prohibition against “considerations outside those quoted in regular contracts.”45 The ruling hurt Seattle, too, which had hoped for the popular and capable Kenworthy to at least play second base. Kenworthy replied that he had been unjustly suspended.46

On March 2 Landis gave Kenworthy permission to train with Portland while his case was under appeal. All agreed that Kenworthy had always been a credit to the game, and various scenarios continued to be discussed to bring matters to some resolution.47 On March 4 he was reportedly traded to Portland for Marty Krug, a deal said to be sanctioned by Landis. And that he would manage Portland.48 He arrived at Pasadena on March 9 to take charge as manager.

The season opened with Kenworthy as manager. But on April 15 PCL President William H. McCarthy said Landis had sent him a telegram ordering that Kenworthy be barred from playing until the case was formally decided. Given that both Seattle and Portland were content with how things had been (they thought) resolved, and subsequent deals made based on that understanding, this seemed inexplicable.49 Landis had required Kenworthy to turn over his telegraphic communications and said he had discovered a telegram from Klepper to Kenworthy back in October urging him to hold out and not sign with Seattle. He was, Landis said, now waiting to hear from Klepper.50

Portland contested Landis’s authority to make such a decision to have Kenworthy reinstated. On May 29 it was announced that Landis had suspended Klepper and Portland VP James R. Brewster, and made Kenworthy property of the Pacific Coast League rather than any given team. Kenworthy was to be suspended until 1924 unless Klepper and Brewster disposed of their ownership interests in the Beavers before them. Portland was also deprived of any interest in Krug. Landis in effect had charged Klepper with inducing Kenworthy to hold out on signing with Seattle until he (Klepper) purchased the Portland ballclub.51

Kenworthy had played in eight games for Portland, batting .364 in limited duty, before his suspension. That remained his record for 1922. He apparently did draw his full salary for the year, the more serious charge being against Klepper.

On December 8, 1922, the American Association’s Columbus (Ohio) Senators announced they had signed the since-freed Kenworthy for 1923, purchasing his contract from Portland. It was, however, a one-year deal, with Kenworthy to return to Portland in 1924, once he was again eligible to play for them.52

In early 1923, Kenworthy asked to be allowed to practice with the Beavers; Landis said no.

Kenworthy went to Columbus. He proved he still had it. He appeared in 131 games, playing second base and batting .305. The team finished in fourth place. In December, Portland “recalled” him, to manage in 1924.

Kenworthy owned some stock in the club, perhaps a considerable share. In July, the Oregonian wrote, “It was largely because of Kenworthy’s stock ownership that he was made manager his season in place of the popular Jimmy Middleton.”53 Middleton had led the Beavers to third place in 1923, their first time in the first division since 1914. The issue was raised because Portland was performing poorly in 1924 and was losing “steadily and nonchalantly.” Gregory said, “Kenworthy, to be frank about it, has lost his grip on the team.”54 The fans had turned on him. There were stories over the next five or six days regarding Kenworthy’s resignation, his denial, and so forth. On July 29 he not only resigned as manager but sold his stock in the club. The stock was said to have been worth $46,250.55

In his final season as a player (and manager), he had appeared in 31 games but hit for just a .221 average.

Kenworthy went into the contracting business in Oakland.

There was still some baseball in his blood, apparently. His name resurfaced in very early 1939 when he was hired by the Oakland Oaks to serve as a spring-training assistant to manager Johnny Vergez. It was an open question whether or not it would work out that he became a coach during the regular season.56 On March 8 in Visalia, he was struck on the right ear by a thrown ball while he was hitting for infield practice. Several stitches were required.57 He did coach third base for the Oaks from 1939 through 1941.

In 1941 and 1942, Kenworthy won the Northern California Senior Golf Championship. He continued his work as a building contractor and remained active in golf tournaments through 1949.

Beginning in 1948, Kenworthy served as freshman baseball coach for St. Mary’s College at Moraga, California.58

On September 21, 1950, he left with three companions on an 18-foot inboard motor boat to do some salmon fishing in Humboldt Bay at Eureka. The four were last seen around 4 P.M. that day but when they did not return, the Coast Guard mounted a search. Kenworthy’s body was found on a beach at 10 P.M. and the boat washed up about half an hour later. The other three were still missing.59

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Kenworthy’s player file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, and Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 His paternal grandfather, William, emigrated from England, dying the year before Bill was born. His paternal grandmother, Mary, was born in Ireland.

2 Some sources list his birth as in Cambridge, Ohio. The specific information regarding the farm birth was provided by his younger brother, Charlie, on a questionnaire submitted to the Hall of Fame in February 1979. Charlie Kenworthy lived in Cambridge, Ohio, at the time. In fact, we cannot be entirely sure even of his birthdate or birth year. Bill Carle, chair of SABR’s Biographical Research Committee, notes that his World War I draft registration card says he was born on July 4, 1887, but his World War II card says July 4, 1886. An Ohio birth index shows James William Kenworthy born on July 3, 1886. We like the “political” connection (William Jennings) and the July 4 date as well. We’ll go with his brother’s seemingly more precise place of birth. We’ll likely never know.

3 “Obituary,” The Sporting News, October 4, 1950: 54.

4 “Duke Kenworthy, Wonder Manager,” Seattle Daily Times, October 9, 1921: 13.

5 “Bears Get ‘Phenom’; Pay $1,000 for a Boston Player,” Rocky Mountain News (Denver), November 19, 1910: 8.

6 Emmons Byrne, “Myriad of Friends Pay Last Respects to Bill (Duke) Kenworthy This Afternoon,” Oakland Tribune, September 25, 1950: 28.

7 Ibid.

8 Kenworthy Will Demand a,Raise,” Denver Post, December 12, 1911: 12.

9 “Grizzlies Lose First Game to Cardinals’ Score 9 to 4,” Denver Post, March 28, 2912: 10.

10 “Bill Kenworthy, Denver’s Great Utility Man, Sold to Washington American League Club,” Denver Post, August 12, 1912: 11. The next day’s Boston Globe reported that Kenworthy had been acquired by the Red Sox. That report proved to be untrue. “To Play With Red Sox,” Boston Globe, August 13, 1912: 13. The Washington Post waited a week but got it right. See “Kenworthy, Denver Star, Bought by Washington,” Washington Post, August 21, 1912: 8.

11 “Griffith Gets a Utility Player,” Duluth (Minnesota) News-Tribune, September 1, 1912: 1.

12 “Hendricks Signs Contract to Lead Grizzles in 1913,” Rocky Mountain News, October 3, 1912: 9.

13 “Kenworthy Coming Back to Grizzlies,” Rocky Mountain News, November 20, 1912: 8.

14 J. Ed Grillo, “Kenworthy Trails Moran to Coast,” Washington Evening Star, December 5, 1921: 12.

15 “Sent Back to Denver by Washington Club, Kenworthy Loses Claim for More Salary,” Washington Post, January 7, 1913: 8. It’s hard to know how Kenworthy was sold to Sacramento in December but it is mentioned in this later story of his having been returned to Denver.

16 “Million-Dollar Player Hasn’t Received Coin, and Will Be in Game,” Star Tribune (Minneapolis), September 2, 1915: 17.

17 “Sire Bill Kenworthy Is Game; Millionaire Won’t Quit Ball,” Sacramento Bee, July 22, 1913: 12.

18 “Seattle Nine Gets Busy,” Los Angeles Times, March 5, 1921: II-12.

19 “Million for a Player,” Sporting Life, September 4, 1915: 9. The same article had run in the August 29 New York Times on page S-3.

20 “Federals After Coast League Men,” Seattle Daily Times, January 10, 1914: 9.

21 “Chicago Giants Will Make Long Journey Into N.W. Country,” Oregon Daily Journal (Portland), January 31, 1914: 7.

22 See “Stovall Carried Off Contracts of Three,” Oregon Daily Journal, February 14, 1914: 6, and “Baseball Sawed Off,” Rocky Mountain News, March 16, 1914: 10.

23 Daniel R. Levitt, The Outlaw League and the Battle That Forged Modern Baseball (Lanham, Maryland: Taylor Trade Publishing, 2012), 249.

24 Harry B. Smith, “Wolverton Chats with Kenworthy, but Makes No Effort to Sign Him,” San Francisco Chronicle, February 21, 1916: 4.

25 “Bill Kenworthy Signs with Oaks to Hold Down Second Base Berth,” San Francisco Chronicle, March 4, 1916: 11.

26 “Kenworthy to the Coast,” Kansas City Star, March 19, 1916: 14A.

27 “Kenworthy Added by Slipping Angels,” Oregonian (Portland), May 14, 1917: 12.

28 “Makeup in Coast League in 1918 Interests Fans,” Salt Lake Telegram, October 30, 1917: 10.

29 “Bill Kenworthy Quits Angels to Build Ships,” San Francisco Chronicle, March 30, 1918: 9.

30 “Seattle to Have Baseball Pennant Contender for Next Year,” Seattle Daily Times, December 21, 1919: 71.

31 “Kenworthy Is Manager,” Seattle Daily Times, November 28, 1920: 34.

32 “Baseball Chatter,” Sacramento Bee, December 7, 1920: 18.

33 “Geary Answers Cry,” Seattle Daily Times, July 12, 1921: 14.

34 “Manager Kenworthy Is Pleased with Support,” Seattle Daily Times, October 2, 1921: 11.

35 “Duke Kenworthy, Wonder Manager.”

36 Ibid.

37 Ibid.

38 “Iron Duke Leaves for South Without Signing,” Seattle Daily Times, October 13, 1921: 17.

39 “President Boldt Says Manager Not Settled,” Seattle Daily Times, October 24, 1921: 12.

40 “Kenworthy Slated to Boss Portland,” Tacoma Daily World, October 26, 1921: 8.

41 “Duke Is Not Free Agent,” Oregonian, December 6, 1921: 13.

42 “Iron Duke Will Play Here Next Year, He Says,” Seattle Daily Times, December 23, 1921: 14.

43 “Thomas L. Turner to Manage Beavers,” Oregonian, January 20, 1922: 14.

44 “Deal to Bring Kenworthy to Portland Seems Likely,” Oregonian, February 17, 1922: 14.

45 “Judge Landis Puts Ban on Kenworthy,” Oregonian, February 19, 1922: 1.

46 “Duke Gives His Version,” Oregonian, February 21, 1922: 13.

47 “Iron Duke to Portland if Seattle Permits,” Seattle Daily Times, March 3, 1922: 19.

48 “Kenworthy Goes to Portland Club,” Rocky Mountain News, March 5, 1922: 10.

49 “Landis Suspends Bill Kenworthy,” Oregonian, April 16, 1922: 1.

50 “Chances Very Slim Duke’ll Play Today,” Oregonian, April 18, 1922: 14.

51 “Magnates Hard Hit,” Bellingham (Washington) Herald, May 29, 1922: 2.

52 “Middleton to Run Local Ball Team,” Oregonian, December 8, 1922: 15.

53 L.H. Gregory, “Kenworthy Runs Beavers Under Iron-Clad Contract,” Oregonian, July 24, 1924: 12.

54 Ibid.

55 L.H. Gregory, “Kenworthy Is Out as Beaver Leader,” Oregonian, July 20, 1924: 12. The article contains a good summary of the difficulties he bore in piloting Portland in 1924.

56 Leo S. Bunner, “Seals Will ‘Woo’ Valley Ball Fans,” San Francisco Chronicle, February 4, 1939: 21.

57 “Kenworthy Hurt,” Oregonian, March 9, 1939: 15.

58 “ ‘Duke’ Kenworthy Funeral Rites Tomorrow,” Oakland Tribune, September 24, 1950: 12. At the time of Kenworthy’s funeral, the other three men remained missing. One was a plastering contactor, one was a motel owner, and one was a tractor salesman.

59 United Press, “Kenworthy Drowned,” Riverside (California) Enterprise, September 23, 1950: 11.

Full Name

William Jennings Kenworthy

Born

July 4, 1886 at Cambridge, OH (USA)

Died

September 21, 1950 at Eureka, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.