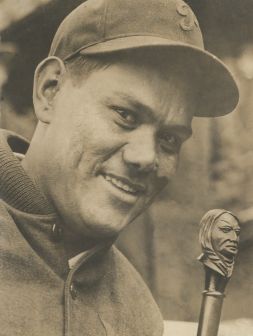

Euel Moore

There have been more than 100 major-leaguers of at least partial Native American descent. Just one was a member of the Chickasaw Nation: Euel Moore (1908-1989). Many folks around Tishomingo, Oklahoma — the tribal capital, where Moore lived much of his life — knew that he pitched for the Philadelphia Phillies and New York Giants in the mid-1930s. Yet plenty of friends and neighbors who knew “Monk” as a state game ranger had no idea of his baseball past.

There have been more than 100 major-leaguers of at least partial Native American descent. Just one was a member of the Chickasaw Nation: Euel Moore (1908-1989). Many folks around Tishomingo, Oklahoma — the tribal capital, where Moore lived much of his life — knew that he pitched for the Philadelphia Phillies and New York Giants in the mid-1930s. Yet plenty of friends and neighbors who knew “Monk” as a state game ranger had no idea of his baseball past.

Take Bill Anoatubby. Now the six-term governor of the Chickasaws, he had just been elected lieutenant governor for the first time in 1979. He had known Monk Moore for years, but was surprised during a visit to Moore’s home to see his team photos hanging on the wall. There was the Wichita Falls Class A team Monk had played with in 1929 and a framed letter accompanying his 1930 contract stipulating $175 a month, noting a $25 raise. Another picture showed the Phillies at spring training in Winter Haven, Florida, in 1935. Monk was a starter in the team’s pitching rotation. He had posted several strong performances during the ’34 season, and at age 27 should have been in his pitching prime. But arm problems stemming from mismanagement ruined his career.

Euel Walton Moore was born near Reagan, Oklahoma (just north of Tishomingo) on May 27, 1908. He was one of nine children born to Charley Harley Moore, a full-blooded Chickasaw, and his wife Daisy Pearl Barger, who was non-Indian. Mr. Moore was a farmer and trader, just eking by, as were most of his friends and neighbors. He spoke Chickasaw, but like many tribal members in the 1920s, thought that speaking it would be an impediment to his children. The kids went to school for a few years, but were needed to work on the farm. Euel completed the eighth grade, nicknamed himself “Monk”, and headed into a life of hard work for little or no gain. He could look at his parents and see himself in 20 years.

Had Moore been born a few generations earlier, he might well have been a great player in the game of Chickasaw stickball. With his large muscular build, athleticism and intensely competitive nature, he would have been a force to be reckoned with. As it was, he arrived as the Chickasaw Nation was dissolving and non-Indians and their culture had come to dominate the local society.

The family moved to Walters, about 115 miles west in Cotton County, OK. There Monk first pitched for pay at age 19. As The Sporting News reported when Moore made the Phillies roster in 1934, he played semi-pro ball for a year or so. Then in 1928, he joined an independent city league in Wichita Falls, just across the Red River in Texas. A local scout recognized the raw talent and signed him to play for the Abilene Aces in the Class D West Texas League in 1929. Moore was 9-3 when he broke his pitching arm on July 20 sliding into second base. Although he pitched no more that season, he battled back and won a spot with Wichita Falls in the Texas League.

The article continues, “he was dropped by Wichita Falls before the 1930 season opened. Later that year Euel joined Muskogee and in 1931 bobbed up with San Antonio.”1 With the seventh-place Indians, he had a 9-12 record and a 4.05 ERA. The highlight of his season was a no-hitter against the last-place Galveston Buccaneers on June 5.

Among other opponents that year, Moore faced Dizzy Dean and Joe “Ducky” Medwick — the stars of the 1934 Cardinals “Gashouse Gang” were then farmhands in Houston. Family lore has it that Monk and Dean once squared off in a 13-inning duel before the future Hall of Famer prevailed. “Diz told me later that he didn’t care who won just so the game would end,” Moore said. If ever that matchup took place, it would have been in this season or possibly an exhibition game. They faced each other as starters once in the National League regular season (on May 11, 1935), but it wasn’t close.

Monk moved to Galveston in July 1932 when San Antonio could not pay all of its players’ salaries. He won 3 and lost 8. But he established himself as a workhorse with the Buccaneers in 1933. He was 17-15, but six of his losses were by one run, and he pitched many no-decision games as he posted a 2.67 ERA. Although it is not known how many innings Moore pitched that season, it must have been around 300 because starting pitchers then were expected to finish games.

He started the 1934 season for the Baltimore Orioles of the International League; Double-A was then the highest classification. On that cellar-dwelling club, Moore’s record of 8-10, 4.04 was actually quite good — allegedly aided by the old frozen-ball trick! In any case, major league teams were interested in him. Rumors circulated until July, when he was dealt to the Philadelphia Phillies for George Darrow, Irv Jeffries, and cash. The Phillies were a perennial second-division team in the National League; although the offense was not bad, they sorely needed pitching. A sportswriter that season noted that they had their best team in a decade, but in July they were still in seventh place (of eight) in the standings.

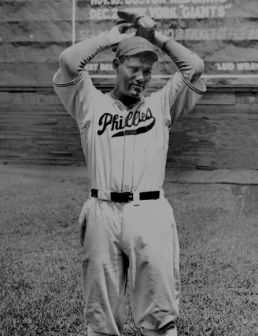

Finally, Moore had realized every ballplayer’s dream: he was a major-leaguer. When he arrived, the team’s publicist described the 6-foot-2, 185-pound hurler as being “built on the lines of an All American guard on one of Pop Warner’s Carlisle teams. He has an arm like a leg, a build of a wrestler. Why, I couldn’t get both hands around his forearm.” Monk made his first major-league start on July 8, 1934 and won, as the Phillies edged the Boston Braves 5 to 3. The newspaper account said he had “hurled like a veteran,” displaying a “great fastball, good curve and fair change of pace.” He allowed ten hits but no walks and “exhibited all the cool craftiness of his race.”

Yes, the sportswriters had noticed that Euel Moore was an Indian and they regularly employed all of the standard clichés of the times. From the beginning of Moore’s pitching career he had been known as “Chief” and in the Philadelphia press he was known to “have on his warpaint” and “tomahawk the visiting team.” One photo in a Baltimore newspaper shows Moore in his uniform wearing a kid’s headdress and holding a hatchet over another ballplayer’s head. The caption read “Moore shows how his ancestors won ball games back in pioneer days.”

Yes, the sportswriters had noticed that Euel Moore was an Indian and they regularly employed all of the standard clichés of the times. From the beginning of Moore’s pitching career he had been known as “Chief” and in the Philadelphia press he was known to “have on his warpaint” and “tomahawk the visiting team.” One photo in a Baltimore newspaper shows Moore in his uniform wearing a kid’s headdress and holding a hatchet over another ballplayer’s head. The caption read “Moore shows how his ancestors won ball games back in pioneer days.”

He was not the first “Chief” to play major league ball, nor even the first to play in Philadelphia, but after a few starts he was being compared to “the immortal Chief Bender,” the excellent Indian hurler for the cross-town Philadelphia A’s. In July he won three more times and lost only once, 2 to 1 to the Chicago Cubs. After one of those victories, Monk complained to teammates about his inability to get a hit. He had been a reliable pinch hitter throughout his career, having batted .324 in Baltimore. The reporter opined that Moore’s hitting woes were “enough to annoy even a wooden Indian, and this Chickasaw is very much alive.”

Although Euel in 1934 was only 26 years old, this was still a little old for a rookie, so he told sportswriters that he was born in 1910, which would have made him only 24.2 By the end of July, the Phillies, behind Moore’s 4-1 start, were showing signs of life. He was now being counted upon by his teammates and the fans. Still, he told a reporter that he was “dead tired” after his first start and was more glad that the game was over than he was to notch his first big-league victory. In his next starts, he was pitching “courageously,” which usually means that his fastball had no pop but he was able to keep enough hitters off-balance with breaking balls and off-speed pitches to win three of four games.

Monk finished with a 5-7 record and 4.05 ERA in 1934. There were other signs that he was arm-weary: just 38 strikeouts in his 122 1/3 innings, which included only three complete games in 16 starts. Like most other pitchers of that era, Euel took pride in completing the job. While finishing the task at hand was and is regarded as a virtue by most of society, pitching was and is an unnatural act — and sooner or later, nearly all arms will break down.

By one account, Moore hurt his pitching arm early in spring training in 1935. He said it happened during an outing in cold weather that was scheduled to be three innings but lasted seven. Manager Jimmie Wilson said it was poor conditioning on the pitcher’s part. The press insinuated that he was not trying hard enough, that he was making too much money, and that this was a “damaging influence.” He was making $850 per month, not a lavish amount, but excellent by Depression-era standards.

When the season started, Moore was hit hard (1-6, 7.81 in 15 games, including eight starts). He was demoted to the Phils’ minor league team in Class A Hazleton, Pennsylvania. Wilson felt that a few victories over minor leaguers would bolster his confidence and show him “there was nothing wrong with his arm.” Euel continued to pitch in pain and ineffectively (4-3, 5.09). But he did not complain much about the pain; if they would not believe him, it was not his way to argue. He would work harder.

On August 12, 1935, the New York Giants obtained Moore conditionally from Hazleton. Desperate for relief pitching, they told the Phillies they would take a chance on Monk, but only if his arm seemed in shape. Moore picked up a win but got racked up two or three times among his six brief outings, and he was sent back to Philadelphia on August 29. His totals for the year were 2-6, 7.45.

That fall, he met Gwyndoline Gray, an Irish girl from Connerville, a town just northeast of Reagan. They were married two weeks before Euel had to report to spring training in 1936. The sportswriters noted that his marriage was just the incentive Moore needed “to reform.” One wrote that Moore “is anxious to make a comeback,” and has been “full of enthusiasm. The Chief tossed a few fast ones the other afternoon that made [manager] Wilson smile.” Moore said his arm was not sore and he expected to win between 15 and 20 games.

Euel was quoted as saying that he “cured” his arm problem by pitching to his brother every day during the off-season. One reporter noted, “At first, the flipper gave him intense pain, but he realized that he was ‘on the spot’ — that unless he showed something he was washed up in baseball, so he gritted his teeth and went ahead.” He was probably telling them what they wanted to hear, but the lack of pain was undoubtedly due to a rested arm.

Although Wilson brought Moore along slowly at first, he let Monk talk him into leaving him in for eight innings late in spring training. While his fastball and curve seemed better than ever, his injured arm apparently had not healed completely and the pain recurred. Subsequently, Moore learned that his injury involved the rotator cuff. Surgery to correct the problem was not available until the 1970s.

Years later, Phillies teammate Dick Bartell told another version of the story:

“There was one pitching prospect I thought Wilson didn’t do right by. Euel ‘Chief’ Moore, an Oklahoma Indian, was a young righthander with a straight overhand delivery. Moore had been bought from Baltimore for about $10,000. According to the catcher, Bill Atwood, who was with the Orioles at the time, the Baltimore manager had used the old frozen ball trick to make Moore look like the greatest thing since Mathewson.

“But Wilson told him he couldn’t throw overhand in [the Phillies’ tiny old bandbox] Baker Bowl. He had to throw sidearm.

“Moore protested that he couldn’t do it without hurting his arm. Wilson insisted. It was pitch that way or not at all. So poor Chief Moore threw sidearm and ruined his arm and never had a winning year. Two years later he was through.”3

But in 1936, Moore only knew that he was not getting anybody out (2-3, 6.96 in 20 games) and again letting down his teammates. In late July, the Phillies released him. His final career totals in the majors: 9 wins, 16 losses, and a 5.48 ERA in 61 games.

Back in the minor leagues, Monk had another brief stop with Baltimore (0-1). In 1937, he played first for Dallas (6-10, 5.24), but the Steers released him on June 29.4 He then appeared with Atlanta (6-5, 3.64) and the evidence suggests he then became a player-coach for the New Orleans Pelicans (no statistics). There is an amusing anecdote from that season featuring Moore and hell-raising pitcher Sig Jakucki.

“According to Arthur Daley in the New York Times, Jakucki and Pelicans manager [sic; records show no sign of this] Euel Moore once went to see a wrestling match after a game. The hefty, playful Moore had the reputation of being the strongest man in baseball, and in Jakucki he found a kindred soul. The wrestling match turned out to be slightly on the boring side, so to provide some excitement, Moore ‘picked up the 200-pound Sig,’ Daley wrote, ‘and tossed him into the ring. The startled grapplers thought Jakucki was merely part of the act and that someone had forgotten to tip them off. But the indignant referee took a swing at Jakucki, a sad mistake.’ Jakucki flattened him. ‘Thereupon the two wrestlers pounced on the interloper, also a mistake.’ Moore joined in until the police broke up the free-for-all and carted Jakucki and Moore to the nearest jail.”5

Moore was still affiliated with the Pelicans as of late March 1938, but the statistics show no signs that he pitched for them that year. He saw semi-pro action in 1938-39, including the 1938 national semi-pro tournament in Denver with the Hubbers of Borger, Texas.6 He then quit playing ball. But when he joined the Army in 1943, at age 34, he told a reporter that he had recently been pitching again and his arm “felt quite swell. I expect to play with service teams and when this war is over I’ll be ready to go again.” His army duties included serving with a selected unit of 110 men, mainly former athletes, at Camp Grant, Illinois. Euel and other major-leaguers such as Bama Rowell and Heinie Mueller helped convalescent soldiers in physical rehab.7

The war lasted longer than he expected. When he was discharged, all hope of a comeback had vanished. He and wife Gwen moved to Tishomingo. According to Gwen, state Senator Joe Bailey Cobb got Euel a job as a state game ranger, a position he held for 27 years. In February 1950, he had a feature role in a story that made national news. A leopard escaped from the Oklahoma City zoo, and in the resulting furor, “members of the police force, highway patrol, Marine reserves, Civil Air Patrol, and Air National Guard combed 100 square miles by land and by air; some 3,000 Oklahomans took part in the search.”8 The wild chase eventually made Time and Life magazines — and Ranger Moore landed on the front page of the New York Times after he helped capture the wildcat.9

In 1954, Monk and Gwen adopted a baby boy they named Larry. During Larry’s childhood, Euel coached Little League and American Legion ball before retiring to his couch with Gwen to watch ball games on TV on Saturday afternoons. “Euel enjoyed the games but usually didn’t reminisce about his career or comment on modern baseball except to say that money was ruining the game,” Gwen recalls. “It wasn’t Euel’s way to complain or talk about regrets. If he had any, you’d never hear about them. He was a happy person who had some setbacks, just like most folks.”

The couple raised Larry and then, in a parent’s worst nightmare, they buried him after he was killed in a traffic accident in 1984. He was 31.

Moore had inherited diabetes and heart disease from his father’s side of the family. His father had died from a heart attack in his fifties. Euel had his first heart attack in 1970, and two more in 1971 and 1973. By 1978, the angina was so bad that he could scarcely shower or shave despite taking increasing doses of nitroglycerine. Finally, he agreed to heart bypass surgery in 1979. He could have kicked himself that he had not had it sooner because the operation transformed an invalid back into an active man and gave him another ten years of life. While he was convalescing in the hospital, another patient — a young man who knew about Euel’s baseball career — considered it an honor to escort him on the walks ordered by the doctor.

Monk was nominated for induction into the American Indian Athletic Hall of Fame in 1984, but when it was discovered that he lacked a Certificate of Degree of Indian Blood he was ruled ineligible. Since inductions took place only every five years, Moore had to wait. He was notified in December 1988 that he had been elected and was slated for induction in May 1989 — but it was just too far away. Monk Moore’s courageous but beat-up heart gave out on February 12, 1989. He was laid to rest in Tishomingo City Cemetery.

Gwen and several relatives attended the induction ceremony, which was held in Tulsa. Allie Reynolds, who had been inducted in 1972, gave a speech praising Euel. Gwen accepted her husband’s plaque from the leader of his tribe, Governor Bill Anoatubby. The Chickasaw Hall of Fame subsequently enshrined Moore in 1996.

Until her death in 2003, Gwen still occasionally received mail asking for Euel’s autograph or any of his old baseball memorabilia. In today’s market, such items have value — but this man probably would not have approved. Shortly before she died, Gwen donated all of Monk Moore’s clippings, photos and other memorabilia to the Chickasaw Council House Museum in Tishomingo. There, he will never be forgotten.

Acknowledgments

This biography has been adapted (with some further contributions by Rory Costello) from an article originally published in The Journal of Chickasaw History, Vol. 2, No. 2, 1996.

Photos courtesy of the Chickasaw Nation Division of History, Research and Scholarship photo archives.

Sources

Much information for this article was obtained through an interview with Mrs. Gwyndoline Moore and by examining her scrapbook of Monk’s baseball press clippings and articles about him. Unfortunately, many individual sources cannot be cited because the clippings did not include either the name of the newspaper or the date.

Professional Baseball Players Database V6.0

Johnson, Lloyd, and Miles Wolff, eds. The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball. 2nd ed. Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, Inc., 1997.

www.retrosheet.org

www.baseball-reference.com

Notes

1 “Wilson Starts Philadelphia Moore Colony,” The Sporting News, August 2, 1934, p. 3.

2 Bill Dooly, “Indian Euel Moore Makes Hitters Do Tenderfoot Dance,” The Sporting News, December 27, 1934: 3.

3 Dick Bartell with Norman L. Macht, Rowdy Richard (Berkeley, California: North Atlantic Books, 1987).

4 Galveston Daily News, June 30, 1937: 8.

5 John Heidenry & Brett Topel, The Boys Who Were Left Behind (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2006): 37. Arthur Daley, New York Times, October 8, 1944: 58.

6 Big Spring (Texas) Daily Herald, July 25, 1938: 2.

7 Abilene (Texas) Reporter-News, October 26, 1943: 17.

8 Rod Lott, “After escaping zoo in 1950, Leapy the Leopard held city in fear,” Oklahoma Gazette, October 3, 2007.

9 William M. Blair, “Leopard Recaptured After Drugging, Dies,” New York Times, March 1, 1950: 1.

Full Name

Euel Walton Moore

Born

May 27, 1908 at Reagan, OK (USA)

Died

February 12, 1989 at Tishomingo, OK (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.