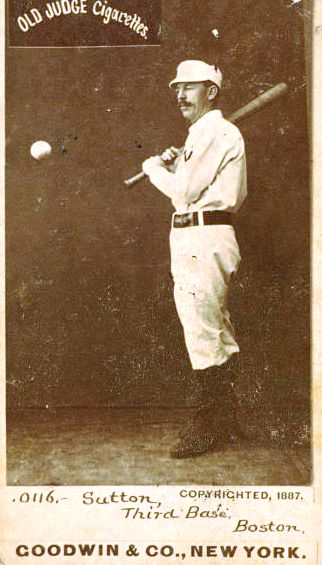

Ezra Sutton

Ezra Sutton matured at the perfect time to join baseball as it morphed from a merely amateur endeavor played by people during the recreational hours to a sport that paid its players, allowing them to pursue their passion as a vocation. Sutton played for teams in the old National Association of Base Ball Players, the National Association and the National League. In fact, he suited up in the first games in both National Association and National League history. The National League itself was formed partly as a result of William Hulbert’s tampering with Sutton and others during the 1875 season.

By the time he was 20 years old, Sutton was being acknowledged as the finest third baseman in the country. He was known for his fearlessness at the position and for having perhaps the strongest arm in the game before an injury reduced its strength to merely average. Many today list him among the elite third sackers of the 19th century.

Sutton enjoyed a robust career for more than 20 years. His retirement did not go as well. After a failed business, he was hit with a debilitating spinal disease characterized by a degeneration of the nervous system. Eventually, he was unable to walk or care for himself. After a horrible accident in which his wife burned to death at the dinner table before his helpless eyes, Sutton was a patient at one care facility after another, which depleted his resources to zero. His plight was only moderately lessened after his old baseball buddies took up responsibility for his care.

Ezra Ballou Sutton was born on September 17, 1849, in Seneca Falls, New York, to Amos T. and Clarinda Sutton. The entire Sutton family, including the parents, were born and raised in New York state. Ezra was the fifth of six children, five brothers and one sister. Amos supported the family as a flour miller. At the time, Seneca Falls was the third-leading flour milling capital of the world, behind only Rochester and Oswego, New York.

By the time Sutton was in his mid- to late teens, he was playing for amateur clubs in and around nearby Rochester. At first Sutton, a right-hander, was a cross-handed batter, like some other players during his era. He changed this approach as pitchers increased their velocity in the early 1870s.

In 1869, at the age of 19, he joined the Alerts of Rochester, an amateur member of the National Association of Base Ball Players. The Forest City club of Cleveland, a professional squad and one of the top western teams, played the Alerts twice in September, once in Rochester and once in Cleveland. Though the Forest Citys soundly defeated the Alerts, they were impressed with Sutton, their opponents’ leadoff hitter and third baseman, and recruited him for the 1870 season. They also enticed second baseman Eugene Kimball to jump the Alerts. Wishing to compete against the top eastern clubs, the Forest Citys revamped their squad for the 1870 season, fielding an entire club of professionals from New York and Pennsylvania.

Despite being only 20 years old, Sutton had already gained a national reputation for his fielding skills. The Buffalo Express called him the “acknowledged third baseman of the country.” The Daily Cleveland Herald seconded that thought on April 25, 1870, noting that he “earned the reputation of being one of the best third basemen in the country.” In 1871 Cleveland joined the National Association, baseball’s first all-professional league. Sutton remained with the club through 1872.

In 1873 Sutton signed with the Philadelphia Athletics. In July and August 1874, he was among a contingent of ballplayers from the Boston and Philadelphia clubs who traveled to England and Ireland to play baseball and cricket. It was baseball’s first overseas tour, an attempt by Harry Wright to interest his native countrymen in his new passion.

On June 26, 1875, Sutton and teammate Cap Anson were recruited by Albert G. Spalding to join the Chicago White Stockings for the 1876 season. Since the agreement was made during the season, it was illegal under National Association rules, as well as a violation of the ballplayers’ contracts. Regardless, Spalding and White Stockings owner William Hulbert forged ahead with their plans. To circumvent punishment for tampering, Hulbert set plans in motion to create a separate league for the 1876 season. The resulting National League remains today as the oldest sports league in the country. Meanwhile, amid pressure from the Philadelphia club and fans, and a promise of a bump in pay, Sutton reneged on his promise to join Chicago, and remained with Philadelphia when the Athletics joined the National League in 1876.

In that fateful 1876 season, Sutton injured his strong and accurate right arm, and his throwing strength was reduced to merely average throughout the rest of his career. He moved to the right side of the infield for the remainder of the season. For the next few years, Sutton split his playing time between third base and shortstop. Throwing problems aside, Sutton was a master of the trapped-ball play by which fielders intentionally dropped pop-ups to trap runners off the bases. (The National League enacted the infield fly rule in 1894 to combat the play.)

Sutton joined the Boston Red Stockings in 1877 for a $1,200 salary, and stayed with the team through 1888. He became one of the most popular players of the era in Boston. The club won the pennant his first two years there. Boston won the pennant again in 1883, Sutton’s first of three straight seasons in which he batted over .300. In 1883 he was among the league leaders in hits, runs, total bases, RBIs, slugging, and on-base percentage. The following year he led the National League in hits and placed third in batting average and fourth in on-base percentage.

Over the winter of 1884-85, Sutton, John Morrill, Jack Manning, Art Irwin, Arlie Latham and Joe Knight formed a polo team, playing the top clubs in the New England area. In 1886 the 35-year-old Sutton spent a good deal of time in the outfield, as young Billy Nash covered third. Nash became Boston’s starting third baseman, a job he kept through 1895. Sutton was relegated to a utility role. Tired of sitting on the bench, he was agitating for his release by 1887. He did have one of his final hurrahs on August 27, 1887, scoring six times against Pittsburgh in a 28-14 romp.

Sutton played in his final major-league game on June 20, 1888, and was dropped by Boston nine days later after appearing in just 28 games that season. He was claimed by Washington at the end of the month, but then the Senators’ management changed its mind. No other major-league clubs showed interest, so the Red Stockings released Sutton outright. On July 10 he signed with the Rochester club of the International Association (the seven-team league had clubs in Toronto, Hamilton, and London, Ontario, as well as Syracuse, Rochester, Buffalo, and Troy, New York) to remain near his hometown. In 1889 Sutton was named player-manager for Milwaukee in the Western Association. He was released in mid-July. The following May he signed as player-manager again, this time for Hartford in the Atlantic Association. He managed the club to a 22-60 record until it disbanded on August 25. After 1890, Sutton played sporadically with some semipro and amateur teams, playing with a club from Auburn, New York, as late as 1896.

Sutton and his wife, Susan, a New Yorker, were married in 1871. They had three children, one of whom died in childhood. After Sutton was released by Boston in 1888, the family moved permanently to a farm in Palmyra, New York, that they had previously purchased. In 1886 Sutton went into the family business, purchasing a stake in a Palmyra gristmill, a facility that grinds grain into flour, with his brothers. The business failed four years later. After that, he worked an ice route for several years and may have owned a piece of the company. Sporting Life wrote that he was doing well in the business in 1897.

At some point during the 1890s, Sutton began to suffer locomotion troubles. Some references cite a flare-up of the problem in 1890, but that is perhaps unlikely as he was still playing ball six years later. He was suffering from the onset of locomotor ataxia, the inability to control body movements. The symptoms started first in his feet; by the end of the decade, his mobility was severely curtailed. A couple of years later, he was paralyzed in both legs. Incapacitated, he relied on his family for support and daily care.

On November 26, 1905, four days before Thanksgiving, Susie Sutton’s dress caught fire at the dinner table when a lamp exploded. She suffered severe burns as her paralyzed husband could do nothing but watch. She died in the hospital six weeks later.

Unable to care for himself, Sutton was admitted to Homeopathic Hospital, a long-term-care facility, in Rochester on April 3, 1906. A couple of months later, he wrote former teammate Tim Murnane, now a sportswriter for the Boston Globe, appealing for help: “I am at the Homeopathic Hospital in Rochester. I came here April 3 suffering from locomotor ataxia. I cannot go out. My sickness was brought on by overwork. The doctor says I used up all my money trying to get cured. My wife was burned to death last January through the explosion of a lamp.” Sadly, he signed the letter “E.B. Sutton, a ball player in distress.”

Murnane published parts of the letter on June 11. Sutton’s old friends and teammates immediately started to take up a collection. His former manager in Boston, John Morrill, personally took up the cause, collecting funds and overseeing Sutton’s care. In September or October Morrill had Sutton relocated to a state facility in Bridgewater, Massachusetts, near Boston, so he could oversee Sutton’s care and allow him to be closer to his friends and former teammates. The relocation actually took Sutton away from his only family, a daughter and two older brothers living near Rochester.

Morrill continued to spearhead the fundraising effort and see to Sutton’s comfort. Sensing the end was near and not wanting to die in a state institution, Sutton had himself moved to a private hospital in Braintree, Massachusetts, in June 1907. He died there on June 20 at the age of 57. Sutton was buried in the Palmyra Village Cemetery.

Sutton’s plight in his final years illustrated to many in the game a need for a system to help indigent ballplayers. The game had always done so, but through individual efforts on a case-by-case basis via fundraising efforts by fans, ex-teammates or league owners and officials. It wasn’t until the formation of the Association of Professional Ball Players of America in 1924 that an organized effort took hold.

Sources

Ancestry.com

Baseball-reference.com

Boston Globe

Buffalo Express

Chicago Daily Tribune

Daily Cleveland Herald

Daily Inter Ocean, Chicago

Ginsburg, Daniel E. The Fix Is In: A History of Baseball Gambling and Game Fixing Scandals. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2004.

Hartford Courant

Johnson, Lloyd, and Miles Wolff. The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Second Edition. Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, Inc., 1997.

Milwaukee Daily Journal

Morris, Peter. A Game of Inches: The Stories Behind the Innovations That Shaped Baseball, The Game on the Field. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2006.

New York Times

Pittsburgh Post

Sporting Life

St. Louis Globe-Democrat

Syracuse Post-Standard

Trenton Evening Times

Washington Post

Waukesha Journal, Wisconsin

Full Name

Ezra Ballou Sutton

Born

September 17, 1849 at Seneca Falls, NY (USA)

Died

June 20, 1907 at Braintree, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.