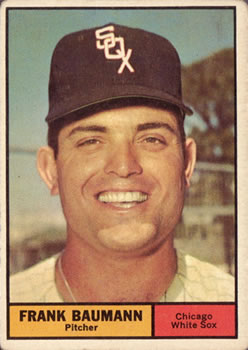

Frank Baumann

One of the premier “bonus babies” of the 1950s, Frank Matt Baumann was born on July 1, 1933, in St. Louis, Missouri. He lived with his parents and younger sister, Rose Ann, on the north side of the city within walking distance of Sportsman’s Park, home field for both the Cardinals and the Browns. Frank’s father, also named Frank, worked as a welder and eventually owned his own business. “Dad was a pretty good semipro pitcher,” said Frank. He received a pro contract when he was about to get married but decided to “stick to regular work.”1

One of the premier “bonus babies” of the 1950s, Frank Matt Baumann was born on July 1, 1933, in St. Louis, Missouri. He lived with his parents and younger sister, Rose Ann, on the north side of the city within walking distance of Sportsman’s Park, home field for both the Cardinals and the Browns. Frank’s father, also named Frank, worked as a welder and eventually owned his own business. “Dad was a pretty good semipro pitcher,” said Frank. He received a pro contract when he was about to get married but decided to “stick to regular work.”1

Beginning at the age of 2, young Frank played catch with his dad in the alley behind their home, throwing on an incline to his dad. The elder Frank insisted his son “throw the ball,” not just spot it into his glove. If he made a wild throw, his dad made him chase the ball down the incline.

Frank played a lot of baseball with other boys from his neighborhood. “We had a bunch of guys that liked to play ball. That’s all we ever did.”2 His first taste of organized baseball came as a member of the Non-Pareils of the St. Louis Khoury League. Frank’s Khoury League coach, Stan Weir, identified his pitching ability and carefully tutored his mechanics. By the time he entered high school, Frank had mastered most of the basics.3

A “big guy” as a freshman, Baumann stood 5-foot-11 and weighed 200 pounds. “When they came to watch me, they’d ask, ‘Who’s that man warming up over there?’”4 He did not pitch often when he started at Central High School, but continued to pitch in Khoury League games. One Sunday, he struck out 17 batters. Vernon Bradburn, Frank’s high-school coach, who also taught world history, read about that game in the newspapers. He confronted his young player when he came to class. “Nice game,” he said. “Seventeen strikeouts in a seven-inning ballgame? Are you kidding?”

Shuffling and stuttering, Frank searched for a reply. “No, well, I just tried to get a little pitching in.” The coach was not pleased. “Turn your uniform in,” he said. Baumann was kicked off the team his freshman year for violating his coach’s policy against playing for another team while on the varsity.5

Frank made the team the next season, 1950, the first year of the Missouri state high school tournament. Coach Bradburn, whom Frank considered one of his greatest mentors, warned him: “Don’t you go playing with anybody else.”6 Before long, Frank set himself apart as “one of country’s outstanding high-school pitchers and a bright big league prospect.”7

Central, labeled a Cinderella team, swept the tournament behind Frank’s pitching in both 1950 and 1951. The next year, Frank picked up the first five tournament wins, and another pitcher won the sixth. Then, in his last high school game, Frank pitched a no-hitter, completing a three-year sweep of the state tournament. He also played outfield and batted .372 in his senior tournament.

These times provided his fondest baseball memories. Later, reporters asked him about his excitement at getting a victory in his first big-league appearance. He replied, “I once pitched a no-hit, no-run game for my high school team in St. Louis. That won the Missouri state championship for us, and it’s the biggest thrill I’ve ever had in baseball.”8 Representatives from reportedly every major-league team watched that championship game. Actual negotiating started as soon as school ended, on Friday, June 13.

The Baumann family and their advisers met with Red Sox representatives Denny Galehouse and Glenn Wright, and received a bid in the $50,000 range. Several other teams made offers, ranging as high as $95,000.9 Cardinals owner Fred Saigh reluctantly considered $70,000. “This is entirely new to me; we’ve never talked in such figures before.”10 St. Louis Browns owner Bill Veeck ate cookies and drank coffee in the Baumann kitchen. “I intended to sign Baumann and pitch him the next day so I could get about half of my money back before the check bounced,” Veeck joked.11

Frank remembered the day the Yankees offered him a workout: “It was a rainy day, and I was supposed to throw batting practice. Bill Dickey put his arm around me and said, ‘Let’s go down to the bullpen. I want to see what you got, kid.’ I threw about 10 or 15 minutes. Walking back [Dickey] put his arm around me and said, ‘Kid, I would love to catch you in a ballgame.’ And I replied, ‘I would love to pitch to you, babe.’”12

Getting a little anxious the following Thursday, Frank told his dad, “C’mon, let’s get some contracts signed. I want to play ball and we’ve wasted almost a week already.”13 The Red Sox had a day game that day, ending their series in St. Louis. Manager Lou Boudreau wanted to start Baumann in the game. But Frank’s advisers wanted to finish negotiating with other clubs.14

The advisers consulted Frank and his dad, taking into consideration not only the money, but also Frank’s interest in the teams. “Dad told me that happiness was more important than a little more money.” About 8 p.m. on June 19, he signed with the Red Sox for a total of $86,000. Relieved that the deal was done, Frank said, “Now let’s go out and get me some hamburgers – three of them. I’m hungry.”15

Baumann’s bonus, the highest price ever paid for the signature of a free agent at that time, came amortized over five years, in an attempt to maximize tax benefits. At Frank’s request, portions went to Frank’s dad in the first two years. The total was guaranteed, regardless of military service, injury, or death. The signing also marked the first time that outside parties assisted a player and his family with bonus negotiations.16 Frank truly appreciated his parents’ support. “There were times when my folks sacrificed so I could keep on playing baseball. I’ll never forget that, and I promised them the first money I made from baseball would go toward getting them a new house. And I did it.”17

Immediately after signing, Frank reported to the Louisville Colonels, Boston’s Triple-A affiliate. Louisville needed pitchers. The Korean War was on and military service had depleted every team’s roster. He threw an impressive seven innings of shutout baseball in his first start, on June 22, just three days after signing his contract. Reports identified him as a “bonus lefty” and “gold-plated rookie.”18 The “bonus” label followed him throughout his career.

Baumann made a very quick transition from high school to the minor leagues. “Here I was an 18- 19-year-old boy, out of high school, coming down with these men that were 23, 24, 25 years of age. But I enjoyed it, because I was a big guy myself.”19 He finished his first season with a 4-6 record, and then began to shine in 1953. Through mid-July, he led his league in both winning percentage and ERA. He contributed with his bat as well, hitting .353, and was selected an All-Star.

In early May that year, Louisville manager Pinky Higgins received Baumann’s draft notice, ordering him to report June 1. The cagey manager withheld the letter a couple of days, allowing Frank to continue to compete.20 Eventually, Baumann took his Army exam in late July and reported to Camp Chaffee, Arkansas, in October, 1953.

Baumann shined in the military leagues. In early 1954, he pitched two no-hitters, missing a perfect seven-inning game by a hit batsman and an error, striking out 17. While on leave in August, he pitched for the Red Sox in an exhibition at Fenway Park. He finished the season with an earned-run average of 0.51, and 147 strikeouts in 70 innings.

In 1955, Frank reported soreness in his left arm, though not a result of anything related to baseball. At Fort Lewis, outside Tacoma, Washington, a former paratrooper became his unit’s sergeant. “Every other exercise he had was push-ups. I built up my muscles too much. When I went to throw I went into a spasm, and nobody could pick this up.”21 This nagging condition plagued him the rest of his career.

After his discharge, Frank went to Louisville for about three weeks. The Red Sox called him up in July. Boston manager Higgins needed help in the pennant race and wanted to supervise Baumann’s training.22 Not even three weeks out of the Army, Baumann helped the Bosox sweep a doubleheader from the Tigers in his major-league debut on July 31, 1955. He got the win, pitching a strong 5⅔ innings in relief.

Frank got his first big-league start on August 11 in Yankee Stadium, but was knocked out in the second inning. Afterward he complained of tightness in his arm while he was warming up. Higgins dismissed the incident as simply a part of “late spring training.”23 The arm trouble persisted, and Frank returned home for some rest, cutting his season short. During the offseason, Frank worked on both his conditioning and his weight. When he left the Army, he weighed 236. By rookie camp the next February, he had trimmed 40 pounds.24

Despite his efforts, Baumann continued to experience arm problems in 1956. He missed part of a road trip, and then was optioned to Albany. Early in July, he picked up his family and headed home again to nurse his sore arm. The ailment threatened to end his career. Medical advisers told him to retire for the year and rest.25 In late September, Baumann pitched batting practice for the Cardinals, where he received assistance from trainer Bob Baumann (no relation).26 Frank said, “I threw normally and without pain. I’m not worried about it anymore.”27

Nonetheless, in spring training of 1957, Boston sent Baumann to Deland, Florida, to train with the Oklahoma City ballclub. He saw a doctor, who found something on the x-ray. Frank returned for a cortisone shot. “One week later, I was throwing. I called that doctor back and thanked him like crazy because he saved my career. I thought I was done.”28

That June Baumann pitched no-hit ball for Oklahoma City for 9⅔ innings, winning in 11 innings, allowing only one hit. He later experienced more arm trouble, and again returned home. Frank tossed a rubber ball underhand to his wife in his backyard, and one day everything miraculously seemed right.29 He won 10 games in the Texas League before rejoining Boston late in the season.

Baumann beat the Yankees in the final game of the 1957 season, and Higgins was impressed. “It’s the first time that Baumann looked something like the kid we first had in Louisville back in 1953. We can sure use him on the Red Sox. We didn’t have a single dependable left-handed pitcher all season.”30 Even general manager Joe Cronin gave Baumann a plug. “It looks as if Baumann has found himself. Everyone is looking for a pitcher to beat the Yankees, and Frank has now won several games from them.”31

Filled with confidence and high hopes, Frank spent this offseason building large industrial boilers in St. Louis. Though he worked hard through cold weather, he thought he would strengthen his bid for a turnaround with strenuous manual labor.32

Early in the 1958 season, Baumann pitched a complete 12-inning win against the Indians and Hoyt Wilhelm. It was Wilhelm’s first start, after 363 relief appearances, and it was Frank’s first major-league complete game. But despite the good start, 1958 became another disappointing season, and Baumann finished with Memphis. To date, Frank had won only seven games in major-league ball, and no more than two in any of his four seasons.

Disappointed with his showing so far, Baumann turned some heads with two victories early in 1959, equaling his highest season total. On May 10, he pitched a complete-game win over Hal “Skinny” Brown and the Orioles, using his bat as well. In the seventh inning, with the score tied 1-1, Brown loaded the bases to get to the bottom of the Boston lineup. Baumann was heading to the plate when “Ted Williams grabbed me by the seat of my pants and pulled me back. He said, ‘Move up in the front of the batting box. But don’t let [catcher] Gus Triandos catch you doing it, because they’ll throw you a fastball.’

“So I kept messing up the ground as I go. I go a little closer, a little closer. I finally got up to the front of the box. He threw a knuckleball, and I hit a line drive with the bases loaded. The center fielder came in, but the ball was hit so hard it skipped over his head. I hit a triple and scored them all. I saluted Ted and said, ‘God, thank you, Ted!’ And he smiled from ear to ear.”33

Baumann completed the 1959 season, his first full season with Boston, with mediocre totals. In just 95⅔ innings, he hardly overwhelmed hitters, averaging just one strikeout every two innings and five walks per nine innings. His six wins brought his total to 13 in five seasons. Showing little sign of a breakthrough, he found himself on the trading block.

Always pursuing a pennant, Boston owner Tom Yawkey tossed a lot of money into the “bonus pot,” leading the major leagues in spending in the early 1950s. Sportswriter Hy Hurwitz suggested that the investment, “to be blunt, has been a large failure to date.”34 The long line of disappointments included, in addition to Baumann, catchers Jerry Zimmerman, Haywood Sullivan, and Jim Pagliaroni, infielders Billy Consolo and Ted Lepcio, and outfielders Marty Keough and Gene Stephens.

On November 3, the Chicago White Sox announced that they had traded for Baumann, in exchange for Ron Jackson, another bonus baby. Jackson had an unsatisfying spring, and appeared in only 10 more regular-season games. Hurwitz termed the trade “one of the sourest deals in Boston history,” as well as a major reason Boston ousted both general manager Bucky Harris and manager Billy Jurges early the next season.35 Veteran writer Joe Cashman added, “the White Sox even got the better hitter in the deal.”36

Frank harbored no bitterness and moved on with a positive mind. “I guess you can’t really blame them for giving up on me, but I wasn’t about to give up on myself.37

Veeck, now owner of the White Sox, rejoiced, “I’ve got you at last.”38 Baumann now teamed with pitching coach Ray Berres, who had helped Bob Shaw improve after a disappointing 1958.39 “The best coaching I got was from Ray Berres, a very dear friend of mine,” Baumann said. “When I got to spring training, he saw what I was doing wrong.”40

Frank came out strong in 1960, with several outstanding relief appearances followed by back-to-back shutouts in June. He continued moving between starting and relieving, and by midseason, Frank had bettered his victory total from the year before and led the league with an ERA of 2.06.

“I learned more with Chicago in four days than I did during my five years in Boston,” said Baumann.41 “I was dipping my shoulder, and I was throwing across my body.”42

Frank finished his remarkable 1960 season with a 2.67 ERA, the best in the majors. He claimed 13 wins and three saves. “I set a goal of 15 wins for myself, and maybe they’ll let me figure I hit it with the saves.”43 The 13 victories matched his total in all his years with Boston. Baumann proved he could successfully pitch out of tough situations, getting a total of 33 double plays behind him, five in one game.

Clearly disappointed at not repeating as AL champs in 1960, Veeck said, “I was positive we’d win it easily, and we blew it. One major factor, he said, was not being able to use Baumann more as a starter, because they had such erratic bullpen help.44

In the opening game of the 1961 season, Frank posted a win in relief, with three shutout innings. Lopez used Baumann because he did not want to lose the opening game, especially with President Kennedy in the house. “Baumann simply is too good a pitcher to be confined to just 100 or 150 innings a year,’ Lopez said. “This season I will use him in relief only in case of great emergency, where I feel that only a left-hander can do the job.”45

The success of the previous season did not follow Baumann very far in 1961. He mixed roles again between starting and relieving in almost exactly the same proportions as before, but with very different results. By midseason, Baumann’s ERA had ballooned over 6.00, the worst on the staff. Lopez was disappointed, saying, “His work this year is absolutely unbelievable. He’s dropping his shoulder and is coming close to side-arm, and his sinking fastball isn’t sinking.”

Baumann ended the year with a monstrous 5.61 ERA. Just one season after leading the majors in ERA, he tied for the most earned runs allowed in the league. He also allowed twice as many home runs (22) and benefited from far fewer double plays (18).

Yet the season had high points. While the country focused on the home run race between Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris, Baumann also found himself in the four-bagger record book. On July 13 at Comiskey Park, Frank and his catcher, Sherm Lollar, hit back-to-back home runs, just the third time in American League history that batterymates went deep back-to-back.46 Baumann hit his only other big-league home run 16 days earlier that year, on June 27.

Then on July 25, Baumann entered the history of the Mantle-Maris race, allowing them back-to-back swats in Yankee Stadium. “One hit the foul pole of the right-field line [296 feet in 1961], and one hit the foul pole of the left-field line [301 feet in 1961]. In any other ballpark they’d been caught or foul balls.” Baumann remembered.47 These were the only home runs Baumann allowed the famous pair in 1961.

The 1962 season brought a lighter workload for the 28-year-old southpaw, and some better results as he added a curveball. “The hitters know I have a few more pitches, so they can’t lay back for the fastball any more,” he said.48 He finished with 10 starts and 30 relief appearances for a 3.38 ERA in 119⅔ innings. He won seven, lost six, and accrued four saves.

In 1963, his sore arm sidelined him again for most of July and August. He worked now mostly as a left-handed relief specialist. His only start of the season, his last as a major leaguer, came in September. He pitched only 50⅓ innings but kept his ERA low at 3.04.

The next season signaled the beginning of the end. By late August 1964, Baumann had an ERA double that of most of the Chisox pitchers. Each of the others was under 3.50, but Frank had a 6.14 ERA. He ended the season with only 32 innings, all in relief, pitching more than two innings in a game only three times. Though only 31 years old, Frank had pitched fewer than 83 innings over the last two years.

Baumann made history again in a seemingly insignificant trade in December 1964, when he was sent to the Chicago Cubs for veteran catcher Jimmy Schaffer; according to the December 2 Chicago Tribune, it was “believed to be the first Chicago crosstown deal in history.” Jerome Holtzman, writing in December 12 Sporting News, agreed it was the first player-for-player trade between the two ballclubs.

The new season was a short one for Baumann. By mid-May he had only four appearances and a 7.36 ERA. On May 22, Frank found himself back in the minors, playing for Salt Lake City, where he pitched just 11 games. His professional career had come to an end.

Like most ballplayers, Frank had nicknames. During his bonus baby days, Red Sox owner Yawkey called him Beau, which fit the proper way to say his name: BOE-mun.49 Later with the White Sox, his teammates referred to him as Bouncy Ball because of his large head. The coaches developed hand signs for different bullpen pitchers to begin to warm up. For Frank, they pretended to dribble a basketball.50

Frank loved to bowl in the offseasons, sometimes with professional bowlers Don Carter and Dick Weber. He entered the Major League Baseball Bowling Championship in 1964, in Tampa, along with ballplayers Jim Bunning, Curt Simmons, Roy Sievers, Jim Gentile, Harmon Killebrew, and Bobby Wine. Many have debated the correlation between pitching and bowling skills, but the issue hardly applies to Baumann. He pitched and batted as a southpaw, but he did most other activities, including bowling, with his right hand.51

After he left the majors, Frank stayed around baseball in St. Louis. He loved throwing batting practice to the Cardinals, which he did for several years, until coach George Kissell pulled him aside.

“Frank, I have to let you go,” said Kissell.

“Why? I haven’t done anything wrong, have I?” asked a surprised Baumann.

“No, no! Those guys don’t want to hit off you. You throw too good!” said the coach, laughing.52

Going all the way back to his playing days in high school, Frank’s coaches never used pitch counts. He remembered several times that he pitched on consecutive days. His advice for pitchers: “Balance and mechanics are very important. A lot of kids hurt their arm now because they come through real fast, and put that leg out stiff. That only lets their arms throw. They’re not using their upper body to throw the ball at all. That’s why they’re hurting their arms.”53

Baumann held several different jobs after professional baseball. He spent more than 15 years with Paramount Liquor and another 15 years with Crown Linen. He also worked for a sporting goods company in the St Louis area and for a discount grocer in Belleville, Illinois.

Frank married Carol Rakers of St. Louis in 1954 and started his family that included four sons (Scott, Ricky, Frankie, and Ted), 10 grandchildren, and, in November 2007, a great-grandson.

He said he still got baseball cards in the mail and enjoyed signing them and sending them back. “I enjoyed baseball very, very much. If I had it all to do over again, I’d be happy to do it. The only thing I regret is that I never got to pitch in the big leagues with the stuff I signed with because I hurt my arm in the Army.”54

Frank Baumann died on December 13, 2020 at Missouri Baptist Medical Center in St. Louis and is interred at the Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery.

Last revised: January 11, 2021

Notes

1 Ed O’Neil, “Baumann New Blueblood of A.L. Hurlers,” The Sporting News, December 21, 1960.

2 Frank Baumann, interview, February 25, 2008.

3 Robert E. Hannon, “Baseball Bonus Baby,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 8, 1952.

4 Baumann.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 Hannon.

8 “No-Hit School Title Contest Biggest Thrill for Baumann,” The Sporting News, August 10, 1955.

9 Hugo Autz, “Bosox Corral Bonus Kids on ‘5-Year Plan’ – Inside Story of Baumann Deal Related,” The Sporting News, July 2, 1952.

10 Autz.

11 “Keen Rivalry for Schoolboys Spurs Bidding,” The Sporting News, June 11, 1952, quoting Bill Veeck in a May 30, 1952 television interview.

12 Baumann.

13 “‘I’m Hungry,’ Frank’s First Words After Contract Talk,” The Sporting News, July 2, 1952.

14 “Not Too Raw for Lou,” The Sporting News, July 2, 1952.

15 “‘I’m Hungry.’”

16 Autz.

17 O’Neil.

18 The Sporting News, July 16, 1952.

19 Baumann.

20 The Sporting News, May 20, 1953.

21 Baumann.

22 Bob Holbrook, “Red Sox Reversing Long-Standing Role as Patsies on Road,” The Sporting News, August 3, 1955.

23 Hy Hurwitz, “Red Sox’ Flag Fate Hangs on 16-Game Trip, Mike Admits,” The Sporting News, August 24, 1955.

24 Gordon (Red) Marston, “Baumann Cuts Off Pounds in Bosox Job Bid,” The Sporting News, February 15, 1956.

25 Hy Hurwitz, “Lefty Blocked Bosox’ Climb,” The Sporting News, October 3, 1956.

26 O’Neil.

27 The Sporting News, October 10, 1956.

28 Baumann.

29 Bob Holbrook, “X-Rays of Ankle Brighten Spring Picture for Ted,” The Sporting News March 12, 1958.

30 Hy Hurwitz, “Red Sox Sniff ‘58 Dividend on Baumann,” The Sporting News, October 9, 1957.

31 Hy Hurwitz, “Southpaw-Poor Millionaires Now Hoping to Hit Jackpot with Three,” The Sporting News, November 20, 1957.

32 Bob Holbrook, “Higgins Sizes Big Baumann as Lefty Ace,” The Sporting News, March 5, 1958.

33 Baumann.

34 Hy Hurwitz, “Some Bosox Bonus Talent in Final Test,” The Sporting News, November 26, 1958.

35 Hy Hurwitz, “Hub Howitzer Wertz Ready for Fast Start” The Sporting News, February 8, 1961.

36 Jerome Holtzman, “New Role for Nye,” The Sporting News, May 12, 1973.

37 O’Neil.

38 Ibid.

39 Jerry Holtzman, “Senor Smiles at Big Bear’s Smooth Hill Form,” The Sporting News, March 16, 1960.

40 Baumann.

41 Walter Bingham, “Go Sox! Stop Yanks!” Sports Illustrated, August 1, 1960.

42 “Baumann May Top Pierce as No. 1 Chi Bargain,” The Sporting News, August 31, 1960.

43 O’Neil.

44 Edgar Munzel, “‘Best Club Blew Flag’ Saddened Burrhead Wails,” The Sporting News, October 5, 1960.

45 Edgar Munzel, “Baumann Nabs No. 1 Chisox Rating, Lefty Earns Starter’s Job,” The Sporting News, April 19, 1961.

46 John C. Tattersall, “Successive HRs by Lollar, Baumann Rare for Battery,” The Sporting News, July 26, 1961.

47 Baumann.

48 “Newly-Developed Curve Ball Has Baumann Back on Beam,” The Sporting News, August 25, 1962.

49 “Here’s Right Way to Pronounce that Guy’s Last Name,” The Sporting News, April 8, 1959.

50 Bob Smith, “Chisox Use Sign Language to Summon Relief,” The Sporting News (quoted from Chicago Daily News), September 29, 1962.

51 John J. Archibald, “Bowling Gets Indorsement [sic] of Major League Pitchers,” The Sporting News, March 21, 1964, and Bob Smith, “Big-Time Stars Will Test Tenpin Skills in ‘Showdown” TV Match,” The Sporting News, March 28, 1964.

52 Baumann.

53 Ibid.

54 Ibid.

Full Name

Frank Matt Baumann

Born

July 1, 1933 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

Died

December 13, 2020 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.