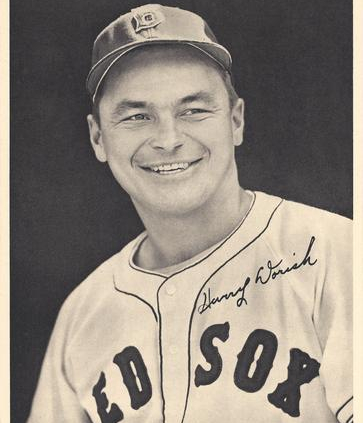

Fritz Dorish

The small mining community of Swoyersville, Pennsylvania, located near Wilkes-Barre, was home to only 5,000 or so inhabitants but gave five ballplayers to the major leagues: Adam Comorosky, Dick Mulligan, Packy Rogers, Steve Shemo, and Harry Dorish. The town also contributed professional athletes in other major-league sports as well. Dorish himself also played football and basketball at Swoyersville High School, and graduated in 1941.

The small mining community of Swoyersville, Pennsylvania, located near Wilkes-Barre, was home to only 5,000 or so inhabitants but gave five ballplayers to the major leagues: Adam Comorosky, Dick Mulligan, Packy Rogers, Steve Shemo, and Harry Dorish. The town also contributed professional athletes in other major-league sports as well. Dorish himself also played football and basketball at Swoyersville High School, and graduated in 1941.

Harry Dorish was not born as Harold, and never had a middle name, but often went by the nickname Fritz. He was born on July 13, 1921, the fourth of five children born to Hritz and Anna Dorish. His oldest brother, John, was a semipro baseball player who reportedly played every position but catcher. With Anna and William preceding him, and sister Mary following, the family was complete. Hritz was a coal miner, whose parents had come from Austria. He died young, of a heart attack in the early 1940s, before seeing his son make the major leagues. William himself was reportedly a good infielder but upon Hritz’s death he had to work hard to help support the family.

Hritz’s wife, Anna, was Czechoslovakian, her family having also come to America in the late 19th century. She worked in a factory for a while, processing silk, but only for a few years before devoting her life to raising the children. Swoyersville was a community built around the coal mining done at the Harry E. Colliery and many of the workers came from Central Europe, as a look at Census data from 1920 makes clear.

In part for this reason, we cannot be 100 percent sure what Harry’s given name truly was. It was not Harold, but was it Hritz or was it Harry? Interviews with his sister Mary Urban, his widow, Eleanor, and his daughter, Barbara Jo German, add the information that his baptismal name was Gregory. The family spoke Slavic languages — perhaps a combination of Russian and Ukrainian. Harry himself completed a questionnaire for the Hall of Fame and cited his parentage as “Russian.” Harry’s wife, Eleanor Uter, was of Lithuanian ancestry, raised in neighboring Luzerne, and knew Harry from high school days. Due to the language barrier, she was unable to talk with Harry’s mother.

Harry was 5’ 11” and 197 pounds. He was often described in the press as “a chunky right-hander” and at times as “pudgy” or as “powerfully built.” He was quiet — one account termed him “reticent” and another “retiring rather than aggressive by nature, at least off the playing field.” After throwing back-to-back no-hitters in high school, striking out 16 against Plains and 18 against Jenkins Township, he quickly got the attention of Red Sox scout Joe Reardon, who signed Dorish as soon as he graduated. Dorish reported to Class C Canton in the Middle Atlantic League, where he appeared in 21 games (7-6, 3.23 ERA) and saw some action in the playoffs against Akron. Dorish pitched for the Scranton Miners (Eastern League) in 1942, his second year in pro ball, and “Schoolboy Fritz” posted a very promising 12-8 record, with a 2.07 earned run average. The Sporting News remarked on his “perfect control” in a 2-0 July shutout of Williamsport. By January 1943, he’d been added to the Double-A roster of the Louisville Colonels, but also added to the wartime National Defense Service roster — one of 17 Louisville players so registered. Harry had volunteered for the Army and was assigned as a cook at Camp Shelby, Mississippi.

Camp Shelby was an active camp during World War II and served as home for both the famous Japanese American 442nd Regimental Combat Team and a number of Women’s Army Corps (WAC) units. It also housed a large convalescent hospital and had a prisoner-of-war camp which contained captured members of Germany’s Afrika Corps.

Dorish advanced within the ranks, attached to a Medical Corps unit sent to the South Pacific, but also got in a fair amount of baseball. A 1944 news story datelined — as many were — “Somewhere in the Pacific,” reported that Sgt. Dorish held a record of 20-3 while stationed and pitching on an undisclosed island. He’d won one game in good part by striking out 24 batters. He was mustered out of the service in January 1946, just in time to make spring training.

As a wartime article made clear, Harry was remembered by The Sporting News as a “hurler with unusual speed.”1 Pitching for the Colonels (of the Louisville variety), Dorish hadn’t lost his touch, and was 11-4 (3.14) at year’s end. Louisville won the American Association pennant and Harry won a couple of the championship games, even driving in a couple of runs in one to help his own cause. By October, he was officially added to the roster of the Boston Red Sox. The Sox were looking forward to 1947, after falling just short of winning the 1946 World Series, and felt they had a trio of new pitching prospects who could bear fruit: Harry from Louisville and both Mel Parnell and Tommy Fine from Scranton. The Boston Post’s Jack Malaney described Dorish in early April as “outstanding among all the rookies Manager Joe Cronin looked over.” He noted that Harry had gotten off to a slow start at Louisville, only reaching full stride by midsummer. “When he got going, there wasn’t any stopping him. He was especially brilliant in the playoffs and Junior World’s Series…Harry has plenty of stuff, but no special fancy stuff, and he specialized on control.”2 His 4-1 record in playoff action secured him an invitation to spring training.

Dorish was so “retiring…by nature” that he had joined the Red Sox train on the way to spring training as it passed through Philadelphia and no one knew he was aboard the train until the following morning. His main pitches were what the Christian Science Monitor called a “heavy fast ball which comes in on a right-handed batter, a sharp breaking curve, a deceptive slider and a baffling sinker.”3 Tex Hughson raved about Harry at the end of March, “Dorish throws that fast sinker ball, an effective pitch at Fenway Park, where the hitters try to lift everything against the high wall in left field.” Dorish was tagged as a starter coming out of spring training, and the Sox were picked to repeat for the pennant, Dorish and Parnell joined forces to blank the Braves on three hits in a preseason City Series game.

Dorish’s big league debut came on April 15, 1947, when he picked up a win on Opening Day. Tex Hughson started and was perfect through the first five innings, mowing down 15 Washington Senators at Fenway Park, but surrendered single runs in the sixth and seventh, and two more in the eighth. The Red Sox still had a two-run lead when Dorish was called on in relief. The bases were full and there were two outs. He got the final out in the eighth, but only after seeing a “tainted hit” — a wind-blown fly — fall in behind Eddie Pellagrini, Johnny Pesky, and Ted Williams behind third base. It went for a double and scored the runs that tied it for Washington. The Red Sox scored a go-ahead run in the bottom of the eighth; Harry pitched a scoreless ninth — two grounders and a strikeout — and got the win. After the game, manager Joe Cronin said, “Didn’t Harry Dorish step in there and do a nice job? He had all the coolness and poise of a veteran.”4

Just four days later, Dorish won his second game, again in relief of Hughson. He let in one run in the eighth, in part due to his own throwing error, but Philadelphia’s 2-0 lead was erased by a ninth-inning Ted Williams home run and the Red Sox won the game in the 10th on Dom DiMaggio’s two-out bases-loaded single. Harry had held the A’s hitless in both the ninth and 10th innings. After a third win in relief, Cronin gave him his first start on May 16 and he shut out the Browns for six innings before giving up a three-run homer. He held on to win the 12-7 game against the Browns. But he lost his share of games, too. Dorish appeared in 41 games for the Red Sox in 1947, starting nine of them and finishing 12 (two complete games) and posting a record of 7-8. His 4.70 ERA was one of the highest on the staff, but he ate up 136 innings and impressed enough to be invited back under new manager Joe McCarthy in 1948.

It was but for a brief stay, however, as Harry spent most of the season with the Birmingham Barons. Designated for the bullpen from the get-go, he was 0-1 for Boston in nine appearances, used only infrequently. In mid-July he was sent down to Birmingham when Mike Palm was elevated to the big-league club. Dorish was 9-4 for the Barons in 99 innings of work with a 3.45 ERA in the Southern Association. The team won the Shaughnessy playoff, upsetting pennant winner Nashville in part due to the slugging of Walt Dropo and the 9-0 shutout Dorish threw in the fifth and deciding game. In the Dixie Series that pitted the Southern Association winner against the Texas League winner, Dorish lost the opener but Birmingham beat the Fort Worth Cats 5-3 in the fourth game of the five-game series.

In 1948, Harry and Eleanor Uter married. They’d known each other since high school days, but Harry wanted to wait until he’d become established in the game. He came to spring training a little heavy in 1949 and was seen to be in some disfavor as a result. He got a little early-season work, but when Boston had to cut down to the 25-man limit he was optioned to Louisville on May 18. He toiled for the Colonels for a couple of months, recalled on July 24 but not used by McCarthy late in the season. McCarthy was later criticized for utilizing neither Dorish (2.35 ERA) nor Frank Quinn (2.86) but relying on the then less effective veterans Tex Hughson (5.33 ERA) and Earl Johnson (7.48). Harry’s year-end stats showed him with just eight innings pitched and no decisions. With Louisville, he’d been an unimpressive 3-3, 5.10. Only a few weeks into the 1950 season, he was sold to the St. Louis Browns for an undisclosed amount of cash. The Browns were 58-96 that year, and Harry’s 4-9 was in the same range with a poor 6.44 ERA. One of the low points was starting against the Red Sox on June 7, chased after 2 1/3 innings while Boston racked up a 10-0 lead through the first three frames on its way to a 20-4 victory — overshadowed by the next day’s 29-4 slaughter of St. Louis. The high point might have been a move just five days earlier that has Dorish still in the record books: he was the last American League pitcher ever to steal home plate. It came on the front end of a double steal that he worked with Ray Coleman. He hit one of his seven career extra-base hits — all doubles — and drove in a run as well in his complete game, 9-3 win over Washington.

The Browns wanted Harry to develop a curveball, and sold him to Toronto at the end of the season, but the White Sox selected him in the November 1950 Rule V draft. Toronto hadn’t officially announced the sale, since they were waiting for some pictures to be sent from St. Louis, and Chicago GM Frank Lane later admitted that he had overheard Browns owner Bill DeWitt tell Commissioner Happy Chandler that the Browns were releasing Dorish. After a few rounds of drafts, there was no one left on Chicago’s wish list so when it was their time to select, Lane recalled what he’d heard and said, “Dorish of Toronto.” That left it to the Browns to explain how a player apparently still on their roster had been drafted by another major league club [See, among other sources, The Sporting News of October 1, 1952]. White Sox manager Paul Richards was even more pleased during spring training when Harry did well: “He has been retiring the hitters with such ease it looks almost ridiculous,” Richards said. “It’s still early, but he certainly has earned himself a good long look.”5

Harry made the club and was subject to an interesting Richards tactic on May 15 that was told and retold over the years. With Dorish pitching with a one-run lead, and Ted Williams due to lead off the bottom of the ninth, Richards wanted lefty Billy Pierce to pitch to Ted, but he wanted Harry to face the rest of the order. So he beckoned in Pierce, but positioned Harry at third base in place of Minnie Minoso. Ted soon popped up and Dorish took over on the mound again, while Floyd Baker came in to play third. The Red Sox did score one run, but Nellie Fox’s two-run homer for the White Sox broke the tie in the top of the 11th and Harry held on to collect the win.

Richards started Harry four times, but preferred to use him in relief. “Dorish is the kind of pitcher you can’t gauge quickly, but the hitters catch up with his stuff when they have several innings to look him over,” Richards said.6

During the season, Harry and Eleanor tragically lost their seven-month-old daughter, Rozanne, to dysentery at home. Harry had come down with a sore arm a couple of days before and took off a couple of weeks before returning to action. By year’s end, Dorish was 5-6 with a 3.54 earned run average. The couple later had two other children, Gregory, who played well in high school ball but suffered bad knees and today works painting houses, and Barbara Jo, a speech language pathologist at the Delaware School for the Deaf.

Dorish was often used in long relief. In 1952, he pitched 91 innings in 39 appearances, with just one start. He led the league with 11 saves and had an 8-4 record with a very good 2.47 ERA. He readily credited part of his turnaround to Paul Richards, who taught him the “slip ball” during spring training, a variation of the palm ball. “I never learned as much pitching in my entire career as I have in the two years I have been with the White Sox,” Harry said after the season. “Nobody ever showed me much of anything about the finer points of pitching before. …Coaches on the other clubs might give you a few tips now and then, but they wouldn’t work with you over any extended stretch. Richards is different. He sticks with you. When you’re pitching, he’ll tell you what you’re doing wrong even if you happen to be getting them out.”7 The man General Manager Frank Lane called “our star relief man last season” had been headed back to the minors before he picked up the palm ball. Harry called the pitch “The Thing” and pledged to keep it a secret. His favorite pitch remained the sinker, though. It was the sinker that troubled Ted Williams so much that, during Harry’s first years with the Red Sox, The Kid had refused to bat against Dorish in batting practice.8

Heading into 1953, Paul Richards said he felt that Dorish, Aloma, and Kennedy gave the White Sox the “most reliable bullpen in the league.” But in both 1951 and 1952 Harry “had to carry virtually the entire bullpen load for the early months in both seasons. It unquestionably affected his later effectiveness.”9 Edgar Munzel of the Chicago Sun-Times called him “one of the best in the business.” In 1953, Dorish got in his most work ever, though, and was 10-6 (3.40 ERA) with 145 2/3 innings of work (including six starts), and in 1954, he threw over 100 innings again, this time with a 6-4 mark and a 2.72 ERA. In 1955, though, the White Sox traded him to the Orioles for catcher Les Moss (and apparently included $25,000 in cash as well). Chicago was looking for more in the way of offense, and Harry’s mentor Paul Richards was the GM and field manager in Baltimore. Dorish was 2-0 with a 1.59 ERA at the time of the trade to the last-place O’s. With Baltimore, he shared bullpen duties with George Zuverink and was 3-3 with a 3.15 ERA.

Harry finished his pitching career with the same team he’d begun with: the Red Sox. After 19 2/3 innings in 1956 with Baltimore without a decision, and a couple of months after receiving 12 stitches in his heel after being spiked by Clint Courtney, he was placed on waivers and claimed by the Red Sox on June 25 for the $10,000 waiver price. The Sox needed help in the bullpen and summoned Dorish. Harry didn’t see a great deal of action, and was 0-2 with a 3.57 ERA. Minneapolis GM Rosy Ryan tried to get Dorish from the Red Sox in August, but Harry had to consent and declined to accept the transfer. On October 9, 1956, he was given his unconditional release.

Not ready to give up yet, Dorish signed on with the San Francisco Seals for 1957. Fortuitously, he may have saved a woman’s life during the March 22 earthquake that hit the Bay Area. A Sporting News bit says he was near the team hotel when he saw a woman standing in front of a large plate glass window and “acting instinctively, grabbed her out of harm’s way just as the window fell with a crash to the sidewalk.”10 Just two days later, the Red Sox played an exhibition game against the Seals in San Francisco and eked out a 5-4 win in 10 innings. Harry had started and kept it close. Harry started the regular season nicely with a 3-0 Opening Day shutout in the Seals’ final season and got off to a 3-0 start in wins and losses, but wound up as 9-12 with a 3.32 ERA in the Pacific Coast League. He played for Minneapolis in 1958 (3-3, 2.23) and started 1959 with the Millers, too, but was acquired by Houston — only to be cut loose “to make room for new arrivals.” He appeared in only four games combined, for a total of eight innings with the two clubs. His final decision was a win. It was the end of the road as a professional player. He’d appeared in 323 major league games, with a 45-43 record and a career 3.83 earned run average.

Harry promptly took a scouting position with the Red Sox. When newly-named manager Johnny Pesky appointed Dorish as his pitching coach for the 1963 edition of the Red Sox, Harry had been a regional Sox scout for three years (1960-62), and had helped out Pesky as Seattle’s pitching coach during spring training when Johnny managed the Rainiers (1961-62).

Harry is not credited with any signings as a scout, and it appears that his work was more as a talent evaluator and roving instructor. One of the pitchers Harry helped in the spring of 1961 was Dick Radatz. According to Radatz, Pesky had Harry work with him in an effort to convert Radatz to relief work: “Because of the fact that I was a one-pitch pitcher, and that being the fastball, they taught me how to warm up rather quickly as opposed to maybe taking 15 minutes to come into games on a minute’s notice.”11 Pesky says it was Dorish’s idea that led to the birth of The Monster, who had a great — if brief — run as an overpowering relief specialist. “It was a wonderful suggestion,” Pesky told writer Hy Hurwitz. Radatz told Hurwitz, “Harry is the guy who introduced me to the bullpen.”12

When Sam Mele took over as Twins manager after the 1961 season, he reportedly considered Harry as pitching coach but Harry continued to work for the Red Sox. And when Pesky was named Sox manager after the 1962 season, Harry had his ticket back to the big leagues. Pesky replaced Sal Maglie with Harry as his pitching coach.

The first notable change that Dorish introduced in Red Sox preparation work was to require the pitchers to run a lot, to keep them stronger and in better shape. Pesky and Dorish agreed on another innovation — which has since been adopted widely: the following day’s starting pitcher would be the one to chart the current day’s game and discuss the results with the catchers and coaches.13 The emphasis on running may have hurt Harry’s longevity with the ballclub. Pesky says that some of the pitchers complained to GM Mike Higgins, who fired Dorish the very day the last game of the 1963 season was rained out. Higgins didn’t do it himself, though. He forced Johnny Pesky to fire his friend. Higgins’ drumbeat to fire Dorish had started about a week before the end, and tore up Johnny, who tried to plead with the GM. Being forced to fire a colleague whose work he admired was, he said, “the only thing I resent in my whole baseball life.”14 Bob Turley was installed in Harry’s stead.

Harry quickly found work scouting for Houston, which he did for three years through 1966. In February 1967, he was named manager of the Jamestown (New York-Penn League) Class A farm club of the Atlanta Braves. In November, Braves VP Paul Richards named Dorish as pitching coach for the Braves beginning with the 1968 campaign, replacing Whit Wyatt. Among the Braves hurlers who credited Harry for important help were Ron Reed, Cecil Upshaw, and Phil Niekro, who praised both Harry and manager Luman Harris: “They changed my motion,” Niekro said. With his altered delivery, Niekro said, he was able to stop aiming his knuckleball and just let it go. “I throw the knuckler harder and with better control.”15

After four years with the Braves, Harry was offered the proverbial role of “another job in the organization” when Lew Burdette was named to take over pitching coach duties in 1972. In this case, the new position was a rather similar one as pitching instructor in the minor league system. Dorish did that for two seasons, then moved to the Cleveland Indians system in the same capacity. He worked for the Indians from 1974 through 1976. No reasons were given for the dismissal of Dorish and two minor league managers at the end of the 1976 season. Lee Stange took his place — but resigned just a month later to become major league pitching coach for the A’s. Harry hooked on with the Pirates in January 1977, replacing Larry Sherry — who’d been elevated to the big league club — as their minor league pitching coach starting in 1977.

In November 1981, Harry joined yet another organization, signed by the Cincinnati Reds as their minor league pitching instructor. He held the position through 1988.

After fully retiring from the game, Harry enjoyed a much quieter life, partly as an avid golfer frequently on the links. He did occasional volunteer work with the Make-A-Wish Foundation, but in later years suffered from a progressive neuro-muscular disease. He never reached the point of becoming wheelchair-bound and died of complications on the last day of the millennium, December 31, 2000.

Note

This biography originally appeared in the book Spahn, Sain, and Teddy Ballgame: Boston’s (almost) Perfect Baseball Summer of 1948, edited by Bill Nowlin and published by Rounder Books in 2008.

Notes

1. The Sporting News, November 18, 1943

2. The Sporting News, April 9, 1947

3. Christian Science Monitor, March 11, 1947

4. Christian Science Monitor, April 16, 1947

5. The Sporting News, March 28, 1951

6. The Sporting News, July 4, 1951

7. The Sporting News, October 1, 1952

8. See, for instance, Bob Holbrook’s column in the July 11, 1956, The Sporting News.

9. Edgar Munzel of the Chicago Sun-Times, writing in The Sporting News, March 4, 1953

10. The Sporting News, April 3, 1957

11. Bill Nowlin, Mr. Red Sox, p. 190 (Rounder Books, 2004)

12. The Sporting News, January 19 and February 16, 1963

13. Mr. Red Sox, p. 205

14. Ibid., p. 221

15. The Sporting News, May 10, 1969

Sources:

Interviews with Eleanor Dorish, Barbara Jo German, Mary Urban, and Leonard Urban, all on October 7, 2007.

Photo Credit

The Topps Company

Full Name

Harry Dorish

Born

July 13, 1921 at Swoyersville, PA (USA)

Died

December 31, 2000 at Wilkes-Barre, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.