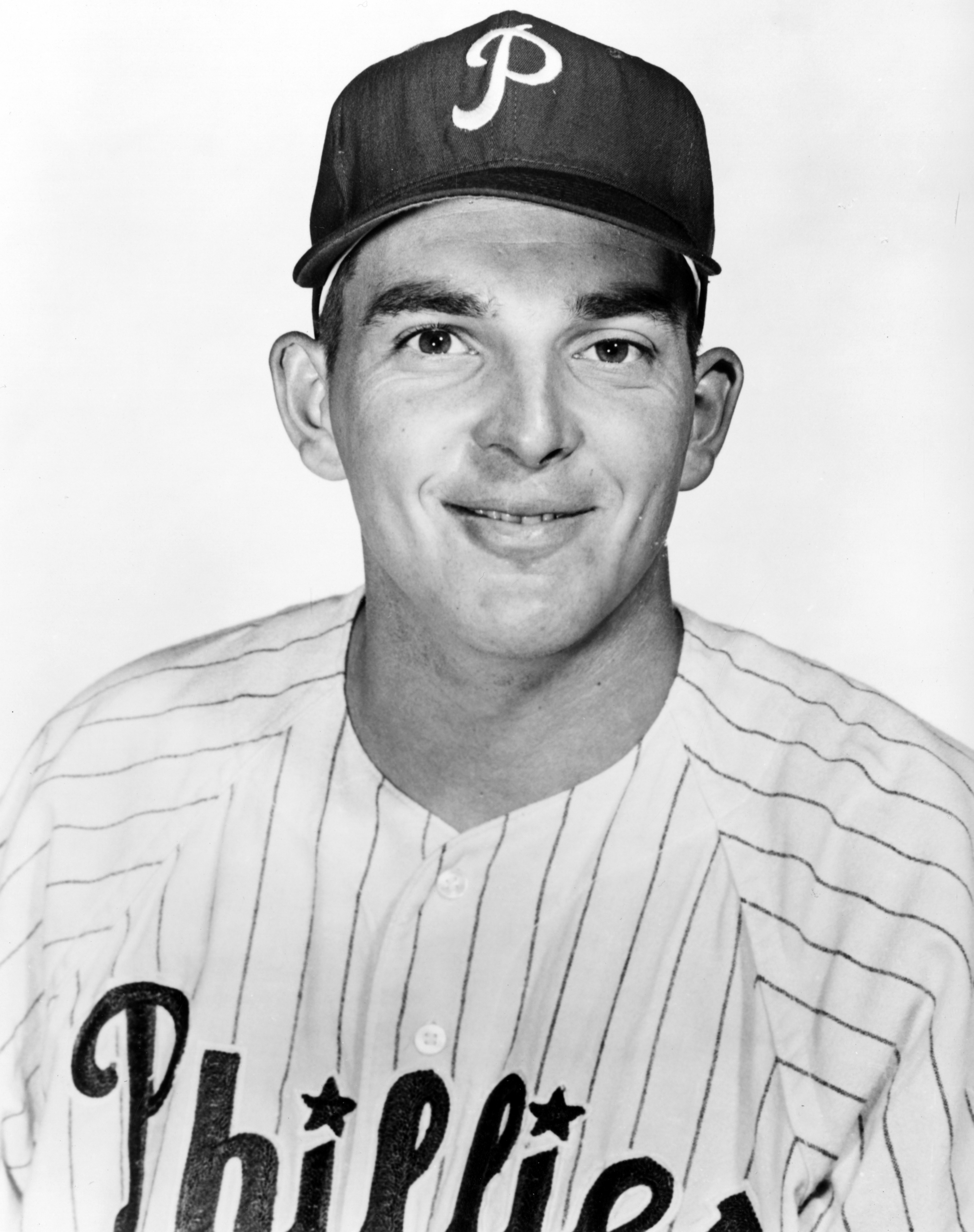

Gary Kroll

Gary Kroll, a hard-throwing right-hander who once pitched 20 consecutive hitless innings in the minors, made his big-league debut for the Philadelphia Phillies on July 26, 1964. Less than two weeks later, the 22-year-old pitcher was gone, traded to the New York Mets for 35-year-old slugger Frank Thomas. Kroll had been regarded as a tremendous prospect because of his size, 6-feet-6 and 220 pounds, and the fact that he’d thrown two no-hitters in the minor leagues and struck out 309 batters in one season. But Kroll never mastered his control and did not last long in the major leagues, pitching for four different organizations in four years.

Gary Kroll, a hard-throwing right-hander who once pitched 20 consecutive hitless innings in the minors, made his big-league debut for the Philadelphia Phillies on July 26, 1964. Less than two weeks later, the 22-year-old pitcher was gone, traded to the New York Mets for 35-year-old slugger Frank Thomas. Kroll had been regarded as a tremendous prospect because of his size, 6-feet-6 and 220 pounds, and the fact that he’d thrown two no-hitters in the minor leagues and struck out 309 batters in one season. But Kroll never mastered his control and did not last long in the major leagues, pitching for four different organizations in four years.

Gary Melvin Kroll was born on July 8, 1941, and raised in Culver City, California, in the Los Angeles metropolitan area. His mother, Billie, was a homemaker, and his stepfather, Howard, had a variety of jobs including security guard and automobile service manager. Gary did not play organized baseball growing up but played in pickup games in vacant lots. He graduated from Reseda High School in 1959.

“When the Phillies signed me I’d never pitched. I worked out at a park in Los Angeles, and a scout named Dan Regan said, ‘Hey do you want to sign?’ I said, ‘Sure.’ He said he would sign me as a pitcher. I said I’d never pitched before, so they sent me to the Instructional League to see what I could do. If I couldn’t do any good, they’d send me back home,” Kroll recalled.1 He signed on June 5, 1959, for a $1,000 bonus.2

The Phillies sent the 17-year-old Kroll to Johnson City, Tennessee, of the Class D Appalachian League. His five victories of Johnson City included a 9-0 no-hitter against Lynchburg on August 3.3

The following season Kroll was assigned to the Bakersfield Bears in the Class C California League. On May 20 he pitched another no-hitter, 1-0 over Visalia, striking out 11.4 He led the staff in starts with 34 and wins with 17 (12 losses), and compiled a 2.91 ERA. The hard-throwing right-hander had 309 strikeouts, the second most in the history of the California League. In one stretch, Kroll pitched 20 consecutive hitless innings.5

Kroll pitched for three teams in 1961, Bakersfield, Des Moines of the Class B Three-I League, and Double-A Chattanooga (Southern Association) He struggled in 1961 (5-19 with the three teams) and experienced his first injury, bone spurs suffered in Bakersfield. But he recovered sufficiently to pitch in winter ball in Puerto Rico.

In 1962 Kroll was 12-2 with 154 strikeouts for Williamsport of the Eastern League, then pitched briefly for two Triple-A teams, Dallas-Fort Worth of the American Association and Buffalo of the Eastern League. Again he was injured, this time a cracked rib, which eventually healed.

In 1963 and 1964 Kroll had identical records of 11-7 for the Triple-A Arkansas (Little Rock) Travelers. “One time I hurled a two-hitter, in Toronto,” he remembered. “The Maple Leaf batter who collected both hits was Sparky Anderson,” the future Hall of Fame manager, Kroll recalled. He said Frank Lucchesi, the Arkansas skipper, was his favorite manager.

Pitching well for Arkansas, Kroll was called up to the Phillies in July 1964. OnJuly 26 at Connie Mack Stadium in the first game of a doubleheader, the Phillies were losing to St. Louis, 4-0, when Kroll was summoned from the bullpen to start the fourth inning. Kroll walked Julian Javier and gave up a double to Tim McCarver. Gordon Richardson struck out but Curt Flood singled to center to score Javier. Kroll gave up a walk and a single in the fifth but retired the side without a run being scored. The Cardinals won, 6-1. “I wasn’t nervous in my debut because I faced most of the Cardinals in the minors, such as Flood, Brock, and McCarver. (But) I was not good in that game,” Kroll said.

On August 2, in another 6-1 defeat, Kroll pitched a perfect ninth inning against the Los Angeles Dodgers. It was his final Phillies appearance. On the 7th he became a Met. The Phillies took advantage of his youth and potential to pry loose Thomas, a power hitter whom they had coveted for years. Kroll was sent to the Mets along with minor-league infielder Wayne Graham for Thomas. At the time, the Phillies held a 1½-game lead over San Francisco. Right-handed power was a weakness for the Phillies, and Thomas was to be the key man in the run for the pennant.6

“Mauch’s theory was to give up whatever they had [to obtain] Frank Thomas, a professional hitter he coveted,” Kroll said. “The organization knew they had an excellent chance to win the pennant. I had no remorse because I grew up with those players. I thought the ’64 club had something special. … They had pros such as Callison, Allen, Bunning, and Rojas. I was disappointed to see them fall short. The Cardinals had more talent, especially with Bob Gibson and Steve Carlton. Cincinnati was excellent also. On the contrary, with the Mets, it was a collection of different people.”

Kroll spent most of his career with the Mets, pitching in 40 games (13 starts) in 1964 and 1965. He was 0-1 for the Mets in 1964 and 6-6 in 1965. He made his first start for the Mets on August 22. He pitched well, striking out eight, but lost, 3-2 to Larry Jackson and the Cubs.

The tenth-place Mets won only 50 games in 1965 and manager Casey Stengel departed in midseason. Stengel was beset but still showed some flashes of humor. In a spring-training game in St. Petersburg, Kroll was being hit hard, and Stengel came out to make a pitching change. “I wanted to stay in the game,” Kroll said. “Casey came out to get me and I said, ‘Casey, I’m not tired!’ His reply was ‘You’re not. But your outfielders are.’ ” Later in spring training, Kroll and Gordon Richardson did combine for a nine-inning no-hitter against the Pittsburgh Pirates in St. Petersburg. 7

“I remember walking the first two batters and Casey came out to talk to me. He said, ‘You’ve got good stuff, just throw strikes.’ ” Kroll retired 18 of the next 19 hitters and Richardson completed the no-hitter.

In his first start of the regular season on April 18 against San Francisco, Kroll was magnificent. In a 7-1 complete-game victory in the second game of a doubleheader that was called after seven innings, he gave up four hits and struck out eight.

On July 25 at Shea Stadium, Kroll faced his former team for the first time. He relieved Galen Cisco for the final three innings of the Mets’ 8-1 victory and got his first big-league save. He yielded 2 hits while striking-out 5. Six days later, at Philadelphia in a 4-3 Mets extra-inning victory, Kroll got the win.

But in the second week of August, Kroll was sent down to Buffalo. “Dick Schaap [a New York-based sportswriter] wrote a funny article about it,” Kroll recalled. “He said that Gary Kroll got sent to Buffalo because he was too good. He had a 6-6 record and it was embarrassing the team. They kept other pitchers and sent me down; it didn’t make sense.” The real reason the Mets sent him down was to work on mechanics. He wasn’t able to stop opponents from running on him. The previous year, Kroll had committed a league-leading four balks.8

On January 6, 1966, the Mets traded Kroll to the Houston Astros for outfielder Johnny Weekly and cash. Kroll saw limited action out of the bullpen. In June he was sent to Oklahoma City of the Pacific Coast League. In nine starts there he was 0-5, giving up 55 hits in 37 innings. He was demoted to Double-A, Amarillo of the Texas League. His manager, Buddy Hancken, “sent his written report to management stating I would not amount to anything. I was annoyed with that because I pitched with bone chips and spurs throughout the season,” Kroll said. (Later he had surgery to remove the bone chips and spurs.) On July 20 Kroll was purchased by Cleveland and was assigned to Reno of the California League. Atseason’s end he had a cup of coffee with the Portland Beavers. The following season, Kroll was spectacular with the Waterbury Indians of the Double-A Eastern League, giving up only 20 hits in 42 innings, striking out 62 batters and posting a scintillating 1.29 ERA.

Kroll began the 1969 season with the Indians, pitching 19 games in long relief, with a 4.13 ERA. He made his last major-league appearance on July 12, relieving Luis Tiant, who was being pummeled in Detroit. Kroll gave up five runs in the second inning, but struck out pitcher Mickey Lolich, the final batter he faced in the majors. The Indians sent him back to Portland.

After the season Kroll played winter ball in Puerto Rico. Lou Klimchock, a Cleveland teammate and now his manager, sent a glowing report to Cleveland management.9 However, the Indians sent him to Hawaii, a California Angels affiliate, in 1970. Manager Chuck Tanner favored the Angels farmhands, and Kroll pitched in only 16 games. In 1971 he pitched for the Tulsa Oilers of the American Association (1-1 in seven games, with one save – preserving a decision for Warren Spahn). That was the end of his career in Organized Baseball.

After he retired from baseball, Kroll stayed in Tulsa and worked in the insurance field. He married his wife, Barbara, after the 1966 season. They raised five children. All of them are like “Pops” – as tall as a doorway. The three boys include Eric, who works with Gary at the insurance agency, Lance, who played basketball in Europe, and Brett, who is 6-feet-6. Daughters are Summer, also 6-feet-6, and described as “being like a tiger,” and Pepper, 6-feet-2, who was an all-state basketball player at Oral Roberts University.

In his brief big-league career, Kroll had success against some of the game’s biggest stars: Willie Mays, Hank Aaron, Eddie Mathews, and Frank Robinson, struggled against him. Kroll whiffed Ernie Banks five times. “Just to pitch to those guys was a thrill. I was like a fan that they let play,” he said in an interview in 2011.

“I remember warming up at Connie Mack Stadium. I was throwing by the big gate along the right-field fence, where the roll-up garage doors were located so the trucks could come from the outside. [Teammate] Ryne Duren watched me,” remembered Kroll. “When you get good and loose, throw one over the catcher’s head,” Duren suggested. “You’d hit the tent, there would be a clang. That noise would go around the ballpark. The first batter I did it to was Willie Mays. He took three swings and left. He didn’t want to hit against me. Sometimes you have a little edge.” Mays was 3-for-10 lifetime against Kroll.10

But “When people ask me who the toughest hitter I faced was, I tell them the truth; all major-league batters that I faced were tough.”

Pitchers Kroll admired included “soft-tossing southpaw” John Tudor. “He knew how to pitch and would change velocity to fool a batter”; Bruce Sutter, with that devastating splitter; and Tim Lincecum, he looks like a little boy, he’s small – but he just led his team to a World Series championship [in 2010].”

Kroll added: “Most people don’t realize pitching is timing. When I pitched and a batter popped out, I was upset because I didn’t strike him out. I would get upset if I didn’t get 10 to 15 strikeouts, and have a monster game like Nolan Ryan. That is not the way to measure pitching! The pitchers I’ve mentioned knew how to get hitters off-balance. Those guys threw a fastball, but relied on a slower changeup. When a batter waits for the changeup, the smart pitcher will throw a fastball just a little harder. It becomes an illusion to a batter. In the 2010 World Series, the Giants pitchers had live arms, devastating changeups, and could change velocity on the ball. The Texas batters swung at a lot of bad pitches.”

Coaching is important for pitchers, Kroll said. “It’s real important that you have a pitching coach to review your work after each game. Casey Stengel was a national treasure, but, in my opinion, when I was with the Mets their coaching staff was poor,” he opined. “The Mets organization hired a friend of Casey’s, pitching coach Mel Harder. Maybe Mel was an excellent pitcher with Cleveland, but communication was non-existent! I didn’t know how to make adjustments and it was frustrating.

“The last year I pitched [at Tulsa], I played for Warren Spahn, a cerebral pitcher. I really liked him. A lot of players didn’t because he [knew] what a player needed to work on. The criterion he gave players was not meant to be condescending. He explained what a player would encounter, how to adjust, develop, and win at the major-league level. Early in my career, I could have used a Spahn or a Bob Lemon to impart their knowledge of the game and work with [me] on the mental aspects.”

This biography is included in the book “The Year of the Blue Snow: The 1964 Philadelphia Phillies” (SABR, 2013), edited by Mel Marmer and Bill Nowlin. For more information or to purchase the book in e-book or paperback form, click here.

Sources

http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/gl.cgi?id=krollga01&t=p&year=1965

Telephone interview with Gary Kroll, February 6, 2011. Unless otherwise attributed, all quotations from Kroll come from this interview.

Notes

1 William J. Ryczek, The Amazin’ Mets, 1962-1969 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland Publishing, 2007), 120.

2 http://www.thebaseballcube.com/players/K/Gary-Kroll.shtml.

3 Dan O’Neill, The Sporting News, June 1, 1960, 37.

4 O’Neill.

5 Steve Treder, Minor League Workhorses: 1956-1960; January 24, 2006: www.hardballtimes.com/main/…/minor-league-workhorses-1956-1960/.

6 Todd Newville, “The Original! Frank Thomas Was A Versatile Slugger Who Made His Own Niche in Baseball”: http://www.baseballtoddsdugout.com/frankthomas.html.

7 Mark Simon, Inside Pitch Magazine, August 2007: http://www.metsnohitters.com/Review.htm

http://theamazingsheastadiumautographproject.blogspot.com/2009_12_01_archive.html. Posted by Lee Harmon; #53) Gary Kroll; February 1, 2010.

8 Baseball Library, Gary Kroll: http://mbwba.whsites.net/reports/news/html/players/player_9942.html.

9 Russell Schneider, “Klimchock Issues a Glowing Report On Tribe Kiddies,” The Sporting News, February 21, 1970, 40.

10 Telephone interview with Gary Kroll, February, 6, 2011; also Ryczek, 120.

Full Name

Gary Melvin Kroll

Born

July 8, 1941 at Culver City, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.