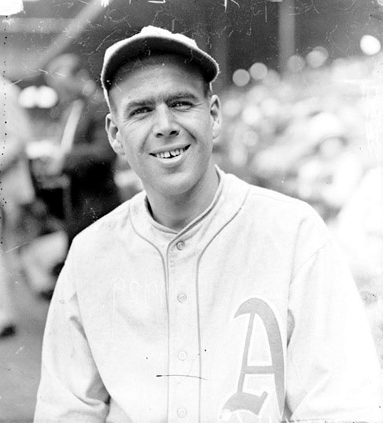

George Earnshaw

George Earnshaw was the right-handed pitching ace of Connie Mack’s last dynasty, but his major-league career started late and ended early.

George Earnshaw was the right-handed pitching ace of Connie Mack’s last dynasty, but his major-league career started late and ended early.

George Livingston Earnshaw was born on February 15, 1900, in New York City, the first of four children of John J. and Maude Earnshaw. One writer described him as “a social register Johnnie” who “knows what to do in case of lobster and artichokes.”1 Whether or not that is true, his family lived in the wealthy community of Upper Montclair, New Jersey, about an hour by train from New York. John Earnshaw is listed in census records as an “advertising agent.”

George attended the prep school at Swarthmore College, a small Quaker-founded school near Philadelphia, and entered the college with the Class of 1923. His Swarthmore connection was the Clothier family of Philadelphia’s landmark Strawbridge & Clothier department store. They were among the college’s leading benefactors and were related to the Earnshaws by marriage. George played tackle on the football team, pitched and played center field in baseball and, at 6-feet-4, was a natural for the basketball team. He joined the Phi Kappa Psi fraternity.

Earnshaw left school without a degree and married a fellow student, Grace Stockton, on June 22, 1922. Her father was the comptroller of the Pennsylvania Railroad.

Another Swarthmore man, pitcher Johnny Ogden, recommended Earnshaw to his boss, Jack Dunn, owner and manager of the International League powerhouse Baltimore Orioles, one step below the majors. Ogden’s younger brother Warren, a pitcher known as Curly, had been Earnshaw’s college teammate.

Earnshaw wanted $600 a month to sign with Baltimore, more than many major leaguers were making. Dunn wouldn’t pay it. Earnshaw called himself the only holdout who never played in a game.

He went to work for an uncle’s barge-transportation company in Newark, New Jersey, and every time the Orioles went there to play the local Bears, Dunn courted the reluctant right-hander. When Earnshaw’s uncle closed the business in 1924, George cast his lot with baseball. He claimed he got his $600 plus Dunn’s promise to pay a full season’s salary even if he was released.

Earnshaw had been pitching in semipro games, but acknowledged that he was rusty when he joined Baltimore. It was August before he rounded into shape. By then the Orioles were running away with their sixth of seven straight International League pennants. Dunn gave the rookie seven starts, and he won them all. He won the fourth game of the Little World Series against the American Association champion, St. Paul.

Jack Dunn had built his dynasty by running an old-school baseball business. Because of his influence, the International was the only minor league that did not participate in the draft, which allowed teams to claim any player in a lower league for a fixed price. Dunn made his living by selling his players to the highest bidder. In 1914, facing bankruptcy after a Federal League team invaded Baltimore, he sent 19-year-old Babe Ruth to the Red Sox for a reported $15,000. In October 1924 Dunn made his biggest deal: Connie Mack of the Philadelphia Athletics paid $100,600 for pitcher Lefty Grove. It was said to be the largest price tag ever for a ballplayer, $600 more than the Yankees had paid Boston for Ruth. Grove had won 108 games in five seasons with the Orioles and averaged 250 strikeouts a year.

With Grove gone, Earnshaw became one of the Orioles’ aces. He won 29 games in 1925 and 22 in 1926. Dunn reportedly turned down a $100,000 offer from Washington for the pitcher. Earnshaw faded to a 17-18 record in 1927, with a 3.77 ERA, and threatened to quit unless Dunn sent him to the majors. He got off to a horrible start in 1928, posting a 6.15 ERA before Dunn sold him to the Athletics in June. “The reported sale price was $80,000,” Earnshaw said later. “How much of that was stage money I never learned.”2

Earnshaw was 28 years old when he joined Philadelphia, where Connie Mack was building his own dynasty. After losing the 1914 World Series, Mack had dismantled his club rather than match the high salaries being offered by the outlaw Federal League, and the Athletics finished last for the next seven seasons. In the 1920s Mack began spending money and collecting new stars: outfielder Al Simmons, catcher Mickey Cochrane, infielder Jimmie Foxx, Grove, and a strong supporting cast. Earnshaw’s teammates on the 1928 A’s included those future Hall of Famers and three others who were now has-beens – Ty Cobb, Tris Speaker, and Eddie Collins – hired by Mack to boost attendance while he waited for his new crop to blossom. The blend of old and new won 98 games and finished second, 2½ games behind the Yankees.

Earnshaw contributed a 7-7 record and better-than-average 3.81 ERA in 22 starts, but walked 100 batters in 158 innings. As he remembered it, he was so wild he never got past the seventh inning in his early outings. He credited catcher Cochrane’s tough-love pep talk for turning his season around. He won his first game in his seventh appearance, a 5-0 three-hitter over Boston, and later pitched another three-hit shutout against the St. Louis Browns.

Poor control would always be Earnshaw’s biggest weakness; he led the American League in walks in 1929 and 1930. At 6-feet-4 and more than 200 pounds, he was a power pitcher who answered to the nickname Moose. He finished second to Grove among the league’s strikeout leaders each year from 1929 through 1931. In addition to his fastball, Johnny Ogden said, Earnshaw had “the best fast curveball I ever saw.”3 In one interview Earnshaw is quoted as saying he threw the curve up to 25 percent of the time; in another interview he said he pitched some games without using it at all. He also featured a changeup that Cochrane called “a kind of half screwball that is quite slow.”4 That sounds like the circle change used by Pedro Martinez and Greg Maddux. Like Grove and many other contemporary pitchers, Earnshaw essayed an elaborate windup with a high leg kick. F.C. Lane, longtime editor of Baseball Magazine, wrote, “Earnshaw lunges forward like an animated catapult.”5

In 1929 Mack’s Athletics began a three-year run as the majors’ dominant team, winning more than 100 games each season. Those seasons saw the height of the offensive explosion that followed the coming of Babe Ruth and clean baseballs. Mack had the hard-hitting Foxx, Simmons, and Cochrane in the middle of his lineup, but Philadelphia won primarily behind a superb pitching staff led by Grove, Earnshaw, and veteran left-hander Rube Walberg. The A’s allowed the fewest runs in the league in 1929 and 1931 and were second-stingiest in 1930.

The 1929 club blew away the competition, taking over first place for good on May 13 and polishing off the Yankees with a three-game sweep over the Labor Day weekend. Philadelphia finished 18 games ahead of second-place New York.

In his first full season, Earnshaw led the league with 24 victories and held opposing batters to a .241 average, the lowest of any pitcher in a league where all batters hit .284. His 3.29 ERA was fourth behind Grove’s 2.81, and his 149 strikeouts were second to Grove’s 170. Grove won 20 games and Walberg added 18.

In the World’s Series, as it was then called, the Athletics faced the Chicago Cubs, whose powerful lineup was predominantly right-handed. Playing the platoon percentage, Mack decided not to start his two lefties, Grove and Walberg. Acting on what can only be described as a wild hunch, he chose a washed-up 35-year-old junkballer, Howard Ehmke, to start Game One. Ehmke had pitched only 11 times during the season, but Mack had sent him to scout the Cubs for two weeks before the Series. He struck out 13, a Series record that stood for more than 20 years, and beat Chicago, 3-1. Ehmke never won another big-league game.

Earnshaw started the second game and struck out seven Cubs in the first 4? innings, but gave up three runs in the fifth. Grove came on to protect a 6-3 lead and held Chicago scoreless the rest of the way, striking out six – the second straight game in which 13 Cubs had fanned. Under American League rules, Earnshaw was declared the winning pitcher since he completed four innings; National League rules required the starter to pitch five innings to qualify. (The five-inning requirement is the rule in both leagues today.)

After just one day off for travel to Philadelphia, Earnshaw went back to the mound in Game Three. This time he lost 3-1, but the two winning runs were unearned. Columnist Westbrook Pegler wrote that the Athletics third baseman, “stout Mr. [Jimmy] Dykes,” committed the crucial error when “his billowy middle obstructed his movements.”6

Game Four was another of the most memorable in Series history. The Athletics, trailing 8-0, scored 10 runs in the seventh inning to win, with Grove picking up the save. Philadelphia staged another comeback in the fifth and final game when outfielder Mule Haas homered in the ninth for a 3-2 victory and Mack’s first championship in 16 years.

After the season Earnshaw’s neighbors in Montclair honored him with a dinner at the exclusive Commonwealth Club. During the winter he closed his insurance office in Buffalo and moved back to Swarthmore with his wife, son, and daughter to open a new agency in the Philadelphia area.

The Athletics claimed the pennant again in 1930. Grove won 28 games and led the league with a 2.54 ERA. Earnshaw added 22 victories and again finished second to Grove in strikeouts, although his ERA ballooned to 4.44.

The 1930 World Series against the St. Louis Cardinals marked the pinnacle of Earnshaw’s career. He pitched 22 consecutive scoreless innings. He won the second game, 6-1, giving up only a second-inning homer to George Watkins, then pitched seven shutout innings in Game Five before he was lifted for a pinch-hitter in a scoreless tie. Grove relieved him and got the victory when Jimmie Foxx delivered on his promise to “bust up the game right now” with a ninth-inning homer.

Earnshaw came back on one day’s rest to win the deciding sixth game, surrendering just a ninth-inning run. In 25 innings he gave up two runs on 13 hits, and struck out 19. An NBC radio microphone, in the Athletics clubhouse for the first broadcast of a victory celebration, picked up Earnshaw’s teammates shouting “Iron Man” when he was introduced. The losing manager, Gabby Street, said, “It was just a case of too much Earnshaw.”7

Hall of Famer Burleigh Grimes, who pitched against Earnshaw in the Series, said years later, “We’d heard about Grove, how hard he could throw. But I’ll tell you, the guy we thought threw the hardest was Earnshaw.”8

The Athletics claimed their third straight pennant in 1931, topping themselves by winning 107 games and finishing 13½ ahead of the second-place Yankees. Grove turned in his greatest season: a 2.06 ERA, less than half the league average, and a 31-4 record, including 16 victories in a row. Earnshaw contributed a 21-7 record and a 3.67 ERA. He again finished second to Grove in strikeouts and held opposing batters to a .288 on-base percentage, trailing only Grove’s .271. On September 5 Earnshaw pitched no-hit ball into the eighth inning before the Boston Red Sox’ Marty McManus grounded a single through shortstop. Earnshaw finished with a one-hitter in an 8-0 win.

In the World Series rematch between Philadelphia and St. Louis, Cardinals rookie center fielder Pepper Martin commanded center stage. Nicknamed the Wild Horse of the Osage for his antic personality and aggressive play, Martin stole five bases and batted .500 as the Cardinals took the title in seven games. Earnshaw pitched well in the second game but lost when Bill Hallahan shut out the A’s, 2-0. He won the Game Four with a two-hit shutout and lost the decisive seventh game, 4-2. Catcher Cochrane was anointed the goat for letting the Wild Horse run wild, but Martin said neither Grove nor Earnshaw knew how to hold baserunners on because they didn’t allow many runners. Martin stole four of his five bases off Earnshaw.

In 1932 Earnshaw’s ERA rocketed up to 4.77 and he gave up a league-leading 28 home runs, but still managed a 19-13 record for the second-place Athletics. On June 3 the Yankees’ Lou Gehrig touched him for home runs in his first three times at bat. As Earnshaw told it, all three blasts cleared Shibe Park’s tall right-field wall. Mack relieved him after the third one, but instead of sending him to the showers the manager made him sit on the bench and watch how reliever Roy Mahaffey pitched to Gehrig. Next time up, Gehrig poled a long home run to left field. “I see,” Earnshaw nodded. “Made him change direction.”9 That quip has been handed down for decades, but the New York Times reported on June 4 that Gehrig’s first two homers off Earnshaw went to left-center. Whatever the direction, Gehrig was the first player in the 20th century to hit four home runs in one game.

After the season, Mack sold three regulars, Al Simmons, Mule Haas, and Jimmy Dykes, to the White Sox for $100,000. He called the deal a financial necessity; the Athletics’ attendance had dropped sharply as the Great Depression took hold, and Mack said he was paying some of the highest salaries in the game.

With at least one-fourth of American workers unemployed, most club owners were feeling the same distress. They responded by cutting salaries. Earnshaw’s paycheck took one of the biggest hits, from a reported $15,000 to $7,500 in 1933. (A few writers did not buy the owners’ whines of poverty. Westbrook Pegler wrote of a “conspiracy” to cut salaries, and financial records later submitted to Congress showed major-league clubs overall had made a profit in 1931, though barely.)

Earnshaw promised to work hard to get his money back, but Mack sent him home from an early-season road trip on the grounds that he was out of shape. On June 3 Mack suspended him for 10 days and fined him $500 “for reporting at the ball park today in no condition to play ball.” The manager added, “I’ve tried to protect Earnshaw for his own sake. Now there’s nothing left for me to do but state facts.”10 New York sportswriter Dan Daniel reported that Earnshaw had been caught sleeping in the bullpen.

By August 17 Earnshaw had won only five games and lost 10 with an ugly 5.97 ERA. Opposing batters hit .311 against him and he struck out fewer than three per nine innings, clear signs that he was no longer overpowering anyone. After he was pounded by the Indians in Cleveland that day, he went home and Mack told him not to come back. Mack bluntly told a United Press writer: “Earnshaw has pleased me at no time this season and I took this action because I did not want to bother with him any more. He didn’t mean anything to us at anytime this season so there was no reason to have him around. To tell the truth I was tired of looking at him and things are more congenial without him. I don’t think he will ever wear an Athletic uniform again.”11 Mack said he would pay the rest of Earnshaw’s salary and would try to trade him.

Mack and the sportswriters may have been tiptoeing around the truth: that Earnshaw was drinking heavily. Later in life he admitted he had an alcohol problem. Years afterward Mack was quoted as saying, “Too bad Earnshaw was a playboy. He liked the night clubs.”12

Connie Mack had bigger trouble than one playboy pitcher. The financial squeeze was severe. Major-league attendance fell 40 percent from 1930 to ’33; the Athletics’ gate dropped nearly 60 percent.

On December 12, 1933, Mack gutted his team. Mickey Cochrane was sold to Detroit for $100,000 and a backup catcher. (As player-manager, he led the Tigers to the next two AL pennants.) Grove, Walberg, and second baseman Max Bishop went to Boston for two undistinguished players and $125,000. Earnshaw and a catcher were sent to the White Sox for catcher Charlie Berry and $20,000. Published accounts said Mack was forced to sell because his bankers had called in loans totaling $250,000, but Mack denied it.

The Athletics did not post a winning record again for 14 years.

Earnshaw joined a Chicago club that had been one of the league’s leading losers since most of its stars were banished in the Black Sox scandal of 1920. The 1934 edition lost 99 games and finished last. Earnshaw’s former Philadelphia teammate Jimmy Dykes became manager in May.

At age 34, Earnshaw rebounded and led the club with a 14-11 record and 4.52 ERA, but again led the league with 28 home runs allowed. He said the White Sox paid him a $500 bonus for every win above 10. He later claimed the team sat him down in the final weeks of the season to save money, but that is not true; he started five games in both August and September.

Earnshaw threatened to retire when the White Sox tried to cut his salary further, but soon signed for 1935, reportedly with the same bonus clause. He was hit hard in his first three starts, and Chicago sold him to Brooklyn in May for the $7,500 waiver price.

Earnshaw won eight games and lost 12 for manager Casey Stengel’s fifth-place Dodgers, with a worse-than-average 4.12 ERA. That summer New York Times columnist John Kieran lampooned what he called Brooklyn’s “Fat Boys’ Club,” including Earnshaw, pitcher Dazzy Vance, and several others, “all of them stout of frame or grand in girth.” Earnshaw shared an apartment with the veteran Vance, who was known to love a good time. Dazzy said, “I do the marketing and cooking. George washes the dishes. We both do the eating, of course.”13 Earnshaw also coached in Vance’s Florida baseball school during several winters.

On April 22, 1936, Earnshaw beat the Boston Braves for his last career shutout. In July, with his ERA above 5.00, Brooklyn sent him to St. Louis in a waiver deal. He pitched primarily in relief for the Cardinals with an ERA over 6.00. The club sold him to its Rochester farm team after the season, but he did not report. His career ended at age 36 with a 127-93 record and a 4.38 ERA, exactly equal to the league average after adjusting for the ballparks where he pitched.

Earnshaw returned to his Philadelphia insurance business. Swarthmore alumnus Eliot Asinof, the author of Eight Men Out, said Earnshaw sometimes pitched batting practice for the college team in the late ‘30s. He pitched occasionally for the Brooklyn Bushwicks, a strong semipro team. In 1938 he and another retired major leaguer, Waite Hoyt, started a Sunday doubleheader for the Bushwicks against the Negro League Pittsburgh Crawfords before a reported crowd of 15,000. Hoyt held the Crawfords hitless for seven innings, but Earnshaw was torched for six runs.

In July 1941 Earnshaw, 41 years old with three children, joined the Navy. Pearl Harbor was still in the future, but Europe was already at war and Americans were being drafted into military service. Former heavyweight boxing champion Gene Tunney had taken charge of the Navy’s physical training program and was recruiting other prominent athletes. Lieutenant Earnshaw was assigned to the Jacksonville (Florida) Naval Air Station. Tunney, a Marine veteran of World War I, insisted that team sports had no value in military fitness training and railed against the commissioning of “fat football coaches” as training officers.14 Historian Donald W. Rominge, Jr. wrote that the Navy had hired Tunney as a public-relations figurehead and paid little attention to his rants. The admirals got their football and baseball teams.

Earnshaw coached the Jacksonville station’s baseball team to a 35-12 record in 1942 and was one of the coaches of a Navy all-star team that played American League stars in Cleveland in July. But when a fellow Jacksonville officer was assigned to sea duty, Earnshaw volunteered to go with him. Shortly after his 43rd birthday he boarded the new aircraft carrier Yorktown as a gunnery officer.

After the Yorktown took part in the attack on the Japanese base at Truk early in 1944, the commander of the Pacific Fleet, Admiral Chester Nimitz, presented Lieutenant Commander Earnshaw with a commendation that read, “With exceptional ability and judgment and considerable calmness, he directed effective anti-aircraft fire against three fast, low-flying torpedo planes and contributed directly in saving his ship from serious damage.”15 Earnshaw was awarded the Bronze Star for his service aboard the Yorktown.

His son, George Jr., a pitcher at Penn State University, joined the Army and was a jungle warfare instructor in the Philippines. He later became a Baptist minister.

After the war Earnshaw decided to make the Navy his career. “He loved it,” his daughter Barbara West recalled.16 He was assigned to the new carrier Princeton. (A previous Princeton had been sunk in the Pacific in 1944.) Earnshaw left active duty in the summer of 1947 with the rank of commander.

Grace Earnshaw filed for divorce a few months later; the decree was granted in April 1948. The couple had two daughters, Barbara and Elizabeth, as well as their son.

Earnshaw returned to baseball in Philadelphia, but not to the Athletics; evidently he and Mack never reconciled. He scouted for the Phillies and was named the team’s spring training coordinator for 1948. When the general manager, Hall of Fame pitcher Herb Pennock, died in January, Earnshaw was one of three baseball men picked to advise the young club owner, Robert Carpenter, who took on the duties of general manager.

From 1949 through 1951 Earnshaw served as the Phillies’ pitching coach. He complained that young pitchers “are mentally lazy. They pitch one day and are brain-dead for the next three.”17 So he ordered tomorrow’s starter to chart the pitches in today’s game (later a common practice) and required pitchers to study the charts of their previous games. He discouraged them from throwing the slider, then a hot innovation: “The slider is killing off more pitchers than tough competition and high living. It is a shoulder-jerker pitch which very few are able to deliver without ultimate injury.”18

In 1950 the Phillies’ Whiz Kids were driving toward their first pennant in 35 years. Earnshaw was assigned to scout their World Series opponent, the Yankees. Rather than hiding out in the stands as most advance scouts did, he strolled into the Yankee clubhouse and began asking the players how to pitch to them. That didn’t work; New York swept the Series in four games.

After the ’51 season, Earnshaw left baseball and settled on a farm near Hot Springs, Arkansas. Like many other players as far back as Cap Anson, he had visited the resort regularly to shape up for spring training by soaking in the 130-degree waters and hiking the mountain trails, but his new home was a long way from the Social Register. His daughter Barbara believed he wanted to escape the demands of fame.

A Little Rock sportswriter visited Earnshaw that winter at his house on a bluff overlooking Lake Hamilton. “I’ve wanted a place like this for a long time,” Earnshaw told him. “I’ve been going full steam, planting a garden and building a henhouse.”19 He said he planned to spend his time raising chickens, farming, and fishing.

He served on the board of directors of the Hot Springs Bathers in the Class C Cotton States League along with another former pitcher, Paul Dean, Dizzy’s brother. He remarried and said he lost interest in baseball as he got older.

George Earnshaw died in a Little Rock hospital on December 1, 1976. The cause of death was not published. His second wife, Hazel, and the three children from his first marriage survived. He was buried in Hot Springs, but in 1992 his widow had the body exhumed and cremated.

Teammate Jimmie Foxx said Earnshaw had the best stuff of any of the Athletics’ pitchers, “but he was only as good a pitcher as he wanted to be, and many times he didn’t want to be.”20

Sources

The Sporting News is the principal source of information about Earnshaw’s career. Other contemporary sources include the Associated Press, United Press, the New York Times, the Chicago Daily Tribune, the Washington Post, the Los Angeles Times, and the indispensable Retrosheet.

Barbara Earnshaw West, the player’s daughter, shared information about her family in an interview on January 14, 2005.

Information about his connection to Swarthmore and the Clothier family came from Susanna Morikawa, curator, and the collections of Friends Historical Library at Swarthmore College.

Alexander, Charles, Breaking the Slump (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002).

Allen, Lee, “Cooperstown Corner,” The Sporting News, November 16, 1963.

Bennett, John, “Jimmie Foxx,” sabr.bioproj.org.

Frick, Ford, “The Star of the Series,” Baseball, December 1930.

Honig, Donald, “Burleigh Grimes,” in A Donald Honig Reader (New York: Fireside/Simon & Schuster, 1988), 579.

James, Bill, and Rob Neyer, “George Earnshaw,” in The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers (New York: Fireside/Simon & Shuster, 2004).

Kaplan, Jim, Lefty Grove, American Original (Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 2000).

Lane, F.C., “The Ace of the Athletics’ Righthanders,” Baseball Magazine, November 1930.

Lott, Jeffrey, “Ninth Man Out,” Swarthmore College Alumni Bulletin, March 2001.

Rominge, Donald W. Jr., “From Playing Ground to Battleground: The United States Navy V-5 Preflight Program in World War II,” Journal of Sport History, Vol. 12, No. 3 (Winter 1985).

Thorn, John, and Pete Palmer, The Pitcher (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1987).

US Census, Essex County, New Jersey, 1910 and 1920.

US Navy website, princeton.navy.mil.

USS Yorktown Association, ussyorktown.com.

SABR member Fred Worth provided information about Earnshaw’s disinterment and cremation in email messages to the author, 2005.

Williams, Peter, When The Giants Were Giants (Chapel Hill, North Carolina: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 1994).

“The Prizes and Penalties of Speed Pitching,” Baseball Magazine, September 1932.

Notes

1 Westbrook Pegler, “Quite a Chap, This Earnshaw,” Chicago Daily Tribune, September 28, 1929, 20.

2 F.C. Lane, “The Ace of the Athletics’ Righthanders,” Baseball Magazine, November 1930.

3 Lee Allen, “Cooperstown Corner,” The Sporting News, November 16, 1963, 23.

4 Bill James and Rob Neyer, The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers (New York: Fireside/Simon & Shuster, 2004), 192.

5 Lane, “The Ace of the Athletics’ Righthanders.”

6 Washington Post, October 12, 1929, 13.

7 Chicago Daily Tribune, October 9, 1930, 18.

8 Donald Honig, “Burleigh Grimes,” in A Donald Honig Reader (New York: Fireside/Simon & Schuster, 1988), 579.

9 The Sporting News, March 31, 1948, 15.

10 The Sporting News, June 8, 1933, 1.

11 United Press-Washington Post, September 1, 1933, 17.

12 The Sporting News, August 27, 1947, 3.

13 New York Times, July 31, 1935, 13.

14 Donald W. Rominge, Jr., “From Playing Ground to Battleground: The United States Navy V-5 Preflight Program in World War II,” Journal of Sport History, Vol. 12, No. 3 (Winter 1985).

15 The Sporting News, October 12, 1944, 16.

16 Author interview with Barbara Earnshaw West, January 14, 2005.

17 The Sporting News, March 23, 1949, 5.

18 Ibid.

19 The Sporting News, February 27, 1952, 20.

20 The Sporting News, August 30, 1945, 2.

Full Name

George Livingston Earnshaw

Born

February 15, 1900 at New York, NY (USA)

Died

December 1, 1976 at Little Rock, AR (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.