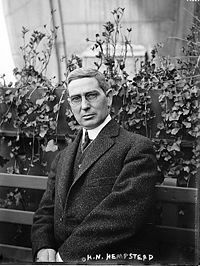

Harry Hempstead

For most of the first 30 years of the club’s existence, the New York Giants were commanded by men of stature in baseball’s executive ranks, team owner-presidents John B. Day (1883-1892), Andrew Freedman (1895-1902), and John T. Brush (1902-1912). Although possessed of dissimilar temperaments and character, the genial Day, the tempestuous Freedman, and the taciturn but iron-willed Brush were all driven men, powerful personalities who helped to shape, for both good and ill, much of the early history of the National League. While these three were exercising their influence, the New York Giants rose in prominence as well, in time assuming the mantle of baseball’s premier franchise. But upon Brush’s death in late 1912, control of the Giants passed to an entirely different kind of helmsman, the cordial but colorless Harry N. Hempstead, executor of the Brush estate.

For most of the first 30 years of the club’s existence, the New York Giants were commanded by men of stature in baseball’s executive ranks, team owner-presidents John B. Day (1883-1892), Andrew Freedman (1895-1902), and John T. Brush (1902-1912). Although possessed of dissimilar temperaments and character, the genial Day, the tempestuous Freedman, and the taciturn but iron-willed Brush were all driven men, powerful personalities who helped to shape, for both good and ill, much of the early history of the National League. While these three were exercising their influence, the New York Giants rose in prominence as well, in time assuming the mantle of baseball’s premier franchise. But upon Brush’s death in late 1912, control of the Giants passed to an entirely different kind of helmsman, the cordial but colorless Harry N. Hempstead, executor of the Brush estate.

Hempstead was a clothing store executive, not a baseball man. His connection to the Giants derived from marriage to Brush’s elder daughter, Eleanor. Although Hempstead had long held nominal positions on the Giants’ corporate board of directors, he had spent most of the preceding decade managing the Brush retail operation in Indianapolis. When he was thrust into the club presidency in December 1912, Hempstead’s primary concern would not be NL pennant races, a matter that he prudently left to authoritarian Giants field manager John McGraw. Rather, it was protecting the financial security of the Brush family women. For the six years that he was club boss, Hempstead maintained a low public profile, presenting a bland but pleasant façade to the sporting press while making little effort to exert influence in league executive councils. During that period Hempstead was privately unsettled by established baseball’s conflict with the upstart Federal League and by the truncation of the 1918 baseball season, an early-September finish being dictated by the demands of American participation in the World War. In January 1919 he divested the Brush family of such concerns, selling a controlling interest in the Giants franchise to Manhattan stock trader Charles A. Stoneham. Hempstead then receded into the background, leaving to Stoneham the enjoyment of the four National League pennants (1921-1922-1923-1924) that lay just on the club’s horizon.

Still, Hempstead’s tenure had not been without its own satisfactions. McGraw had brought home pennants in 1913 and 1917, although the Giants lost the World Series both years. Such defeats notwithstanding, the New York Giants remained major-league baseball’s most prestigious franchise, the top fan attraction in the country’s largest sports market. Perhaps more important to Harry Hempstead, the family’s interest in the club had retained its value, with gate receipts and other Giants revenues being fortified by the expensive rental of the Polo Grounds to the New York Yankees, the Giants’ then downtrodden American League competitor. The 1919 sale of the Giants yielded a healthy profit on investment, leaving Brush family members set for life. By his lights, therefore, Harry Hempstead had faithfully discharged his primary responsibility as overseer of the New York Giants.

Franchise caretaker Harry Newton Hempstead was born in Philadelphia on June 25, 1868, the youngest of six children born to Orlando Gordon Hempstead (1822-1901) and his wife, the former Eliza Tyler (1825-1893).1 O.G. Hempstead, originally from Connecticut, made a handsome living as the head of a customs brokerage firm2 and his children were raised in comfortable circumstances. Although without much experience as a baseball executive when he assumed the presidency of the Giants, Harry was no stranger to the game itself. As a schoolboy he had played on an undefeated high-school team. Upon graduation, Hempstead entered Lafayette College, a top-flight liberal arts/engineering institution in Easton, Pennsylvania. There he leavened a rigorous course of study with extracurricular activities, including playing outfield for the class nine.3 But for the most part, Harry focused on academics, first as an engineering major, thereafter concentrating on chemistry. He graduated with a bachelor of science degree in chemistry in 1891, but not before reputedly blowing a hole in a Lafayette laboratory wall by misadventure with a chemical formula.4

Although trained as a chemist, Harry began his working life in the freight transportation business, serving as vice president of the Morris European and American Express Company in New York City. During that time, Hempstead met Eleanor Gordon Brush, a daughter of Indianapolis department store magnate John T. Brush by his late first wife, Margaret Agnes Ewart.5 Although a significant figure in the civic life of his adopted Hoosier hometown, Brush was more widely known as a major-league baseball team owner, having been principal shareholder of the short-lived Indianapolis franchise in the National League until 1890, and thereafter acquiring control of the National League Cincinnati Reds. On October 10, 1894, the course of Harry Hempstead’s life was irrevocably set when he and Eleanor Brush were married. The subsequent birth of sons Gordon Brush Hempstead (1899) and John Brush Hempstead (1904) would make their family complete.

In 1898 the Hempsteads relocated to Meadville, Pennsylvania, where Harry assumed the presidency of the Garfield Chewing Gum Company. Four years later John T. Brush achieved a long-deferred ambition: majority ownership of the New York Giants. Brush, long a minority stockholder in the New York franchise, purchased a controlling interest in the club from Andrew Freedman, once a fierce Brush adversary in NL executive councils but more recently a strategic ally in the league’s frequent internal fracases. Brush had financed acquisition of the Freedman stock by selling his interest in the Cincinnati Reds to a consortium of local buyers headed by yeast manufacturing millionaire and youthful Cincinnati Mayor Julius Fleishmann. The franchise rearrangements were not without consequence for Harry Hempstead. Wishing to focus his attention on operation of the Giants, Brush prevailed upon his son-in-law to move to Indianapolis and assume oversight of the Brush clothing business, including its flagship retail operation, the whimsically named When Store.6 With Harry serving as store manager and doubling as When Clothing Corporation treasurer, Brush was free to plot the course needed to return the long-mediocre Giants to pennant contention.

In November 1902 Hempstead, “a clever young man,” assumed a position on the board of the National Exhibition Company, the Giants’ corporate alter ego.7 He was reappointed to the board five years later.8 But no actual power vested in that body. Rather, Brush, an intensely competitive man, entrusted club fortunes almost entirely to field manager John McGraw, a firebrand whose zeal to win matched that of Brush. McGraw dealt with everything from player contract signings to in-game strategy, leaving Brush to attend to the costs incurred by McGraw maneuvers and to reap the profits when Little Napoleon brought home pennants in 1904 and 1905, plus the World Series crown in the latter season. But time was running out for John T. Brush. Since 1890 he had exhibited the symptoms of locomotor ataxia, a painful wasting disorder that slowly disables the limbs. By the time he acquired the Giants, Brush’s affliction had progressed to the point where he had difficulty walking without the aid of canes. Thereafter, he was often confined to a wheelchair. Still, Brush drove himself, refusing pain medication that might dull the senses while concentrating his waning energies on the operation of the club’s front office. All the while, son-in-law Hempstead dutifully oversaw Brush’s commercial interests in Indianapolis.

Just before the start of the 1911 baseball season, John T. Brush, his health now irreversibly in decline, received a cruel blow. On April 11 a fire destroyed most of Polo Grounds III, the wooden ballpark that had served as Giants home field for the past 20 years. The Giants’ home season was rescued when Frank Farrell, dominant co-owner of the American League rival New York Highlanders, magnanimously placed Hilltop Park at Brush’s disposal. Failing health notwithstanding, the Giants owner was determined to continue on in baseball. But before rebuilding the Polo Grounds, Brush assayed family sentiments, particularly those of the second Mrs. Brush. Only months before Harry Hempstead and Eleanor Brush tied the knot in 1894, John T. had married Elsie Boyd Lombard, a comely young stage actress barely older than Eleanor.9 Their daughter, Natalie Lombard Brush, was born in January 1896 and was still a schoolgirl at the time of the calamitous fire. Face-to-face with his own fast-approaching mortality, Brush had to weigh the six-figure investment that Polo Grounds reconstruction would entail against the financial cushion that his wife and daughter would require after his passing. Happily for major-league baseball, Elsie Brush agreed to the ballpark rebuild. Once he had his wife’s blessing, Brush summoned trusted son-in-law Hempstead, whose college study of engineering would now be put to good use in minding the construction project for the often bedridden John T.10

In the short term, events played out felicitously. The Osborn Construction Company of Cleveland erected Polo Grounds IV, a commodious concrete and steel structure with an iconic bathtub-shaped playing field, in remarkable time. The Giants were able to resume home games on June 28, 1911, with fans flocking to the new stadium.11 The New York Giants would lead the major leagues in home attendance (675,000) that season, with gate receipts restoring construction-depleted franchise coffers. Even better for Brush’s spirits, the Giants surged in the NL standings, with manager McGraw pulling the strings in masterly fashion. New York posted a league-leading .279 team batting average, stole a major-league record 347 bases, and received the benefit of sterling pitching by the Cooperstown-bound duo of Christy Mathewson (26-13) and Rube Marquard (24-7). In the end the Giants won the pennant handily, finishing 7½ games ahead of the runner-up Chicago Cubs. The only spoiler of the season was the 1911 World Series, lost to the Philadelphia A’s in six games. The 1912 season was a virtual repeat. Pitching aces Mathewson (23-12) and Marquard (26-11) won big, the Giants led the majors in home attendance (638,000), and cruised to another pennant, a full ten games better than the Pittsburgh Pirates. But again, New York hopes for a major-league championship were dashed, with heart-wrenching fielding miscues in the tenth inning of the deciding game providing the World Series-winning margin for the Boston Red Sox. Meanwhile, back in Indianapolis, Harry Hempstead assumed the presidency of the Brush clothing business.

The 1912 National League pennant was John T. Brush’s last hurrah. At a hastily arranged November meeting of the National Exhibition Company board, Harry N. Hempstead was installed as New York Giants vice president and heir apparent to franchise command.12 Shortly thereafter, Brush, attended by a battalion of private nurses, set off on a restorative railway trip to the West Coast. He never made it, dying on board outside Seeburger, Missouri, on November 25, 1912. The dean of National League baseball club owners was 67. Uncertainty followed in the wake of Brush’s death, with rumors rampant that the Giants would be sold by the Brush heirs.13 Harry Hempstead moved swiftly to meet the situation. Days after Brush’s funeral in Indianapolis, Hempstead released a public statement declaring that the family would retain its interest in the New York franchise and that on-field Giants operations would remain in the hands of manager McGraw.14 Shortly thereafter, Hempstead journeyed to New York and was formally installed as president of the New York Giants.

Although well-known in Indianapolis business circles, 44-year-old Harry N. Hempstead was a mystery to baseball fans. The Cincinnati Enquirer informed readers that the incoming Giants boss was “a young man of engaging personality and quiet business temperament … [who had been] a careful and quiet student of the game for many years.”15 His stewardship of the franchise would be aided by the counsel of N. Ashley Lloyd, longtime friend of John T. Brush and his junior partner in the Cincinnati and New York baseball ventures.16 Hempstead and Lloyd would also serve as co-executors of the Brush estate. Apart from nominal bequests, the Brush will left his assets, including a majority stock interest in the New York Giants ballclub, evenly divided among wife Elsie Lombard Brush and daughters Eleanor Brush Hempstead and Natalie Lombard Brush. As Natalie (then age 16) was still a minor, this put Mrs. Brush in effective control of the franchise. Fortunately for baseball, Elsie Brush shared her late husband’s esteem of Harry Hempstead and was content to leave disposition of club affairs to his judgment.

Hempstead repaid the prior kindness of Frank Farrell when the Highlanders lost their lease on Hilltop Park at the end of the 1912 season. For the next ten years, New York’s American League team would call the Polo Grounds home, the club’s rental fee adding an estimated $50,000 annually to the Giants’ balance sheet. Otherwise, Hempstead resolved to maintain the status quo, an intention reflected in the prompt signing of John McGraw to a new $30,000-a-year contract.17 The Giants manager responded by bringing home a third straight National League pennant. But once again, the Giants would fall in the World Series, losing the 1913 fall classic to the Athletics in five games. Soon thereafter, McGraw began to chafe under the new club regime, particularly resenting his diminished influence on franchise direction. During the previous decade he and John T. Brush, kindred spirits and both the product of impoverished upbringing in rural upstate New York, had worked closely together on all aspects of club operation. New club president Hempstead, however, kept McGraw at arm’s length, entrusting his manager with all decisions on player contracts and game strategy, but not seeking McGraw’s input on business and other matters related to franchise welfare – a blow to McGraw’s long-held aspirations to ascend into a front-office post. On matters pertaining to club operation, Hempstead relied upon the counsel of Ashley Lloyd and club secretary John B. Foster.18

Although customarily a listener rather than a talker when in the company of other ballclub moguls, Hempstead was quick to sound the alarm about the menace posed to the 1914 season by the Federal League, a nascent rival organization that had inadvertently solicited the Giants club president to invest in its Indianapolis franchise.19 To reduce player receptivity to Federal League inducements, Hempstead persuaded fellow National League owners to concede certain contract-related demands made by the players, a strategy subsequently rewarded by the loyalty of Christy Mathewson and other New York stalwarts when the Feds came calling. The following January, the steely, unsentimental businessman side of Harry Hempstead was put on rare public display. With the financially strapped International League franchise in Jersey City likely to be overwhelmed by the relocation of the reigning Federal League champion Indianapolis club to Newark, baseball powers proposed to save the Jersey City club by moving it to the Bronx. Such a placement, however, required the permission of the New York Giants, which held territorial rights over the venue. But Harry Hempstead would not grant it. In his view, another professional baseball club playing in New York was incompatible with the financial interests of the Brush family. Notwithstanding pointed criticism by American League President Ban Johnson, International League boss Ed Barrow, and The Sporting News, Hempstead would not yield. As a consequence, the Jersey City Skeeters remained in Jersey City.20 Months later, the Federal League received similar treatment. The plan to relocate a Federal League team to Manhattan was thwarted by Hempstead, quietly dispatching his agents to scoop up the East Side building lots that had been designated as the site for the Federal League team’s ballpark.21

The Federal League expired after the 1915 season, but not before exacting, in the opinion of Harry Hempstead, a fearsome toll on the game’s wellbeing, particularly its minor leagues. Citing calculations by NL officials, Hempstead observed that the minors had contracted from 49 leagues in 1913 to 26 entering the 1916 season, while more than 5,000 former players had lost their place in the professional ranks, all of which Hempstead attributed to the havoc caused by the conflict with the outlaw circuit. “The man who thinks wars are good for base ball has never had anything to do with a club in time of war,” he declared.22 Still, Hempstead, “likeable and affable,” was “at the center of one group of good souls” attending a NL/AL/FL/International League peace conference who counseled reconciliation with Federal League backers.23 One such backer was Harry F. Sinclair, a swashbuckling oil tycoon who had owned the Federal League Newark Peppers and wished to remain in the game. In the winter of 1915-1916, Sinclair set his sights on acquisition of the New York Giants, and rumors of a sale soon abounded. When queried on the subject, Hempstead – ever the businessman – revealed that “while he had received no definite offer for the club, he would sell [the Giants] if the offer was alluring [and] that he was open to proposals.”24 But the prospective sale foundered when Sinclair declined to meet the Hempstead asking price of $2 million for the New York club, an amount that Sinclair deemed “beyond all reason.”25 That outcome was agreeable to many Gotham baseball followers, including influential New York Sun sportswriter Joe Vila, who wrote that “if Hempstead remains in control there will be no regret, inasmuch as he is a clean sportsman and thorough gentleman.”26 Thereafter, Hempstead penned a first-person editorial on the rosy prospects presented by the 1916 season, provided there was improved on-field behavior by players and the game was conducted “according to the theories and ideas of the managers.”27

Unlike his late father-in-law, Hempstead was not fixated on baseball. During his tenure as Giants president, he continued oversight of Brush family business operations in Indianapolis, served as a trustee of his alma mater, Lafayette College,28 and enjoyed winter sporting activities in Lake Placid. But operation of the Giants was never far from his mind. The 1917 season brought a second National League pennant to the Hempstead administration, but things had not gone smoothly. Hempstead’s relations with manager McGraw remained distant, and the Giants roster contained types not to the club president’s liking, particularly volatile second baseman Buck Herzog, whom Hempstead suspended late in the season for refusing to accompany the team on a road trip to Boston. And the season finale again proved a disappointment, the Giants losing the 1917 World Series in six games to the Chicago White Sox. Of far more long-term concern to Hempstead was the effect that American entry into the World War might have on major-league baseball. Although the 1917 season had not been seriously affected by the war effort, 1918 would prove a different story. Player ranks were thinned by the call to military service or work in defense industry plants, the regular season was abbreviated, and the fall classic hurriedly completed by September 11. All the while, attendance at Giants games plummeted. The gate for 1918 home games was only 256,618, barely half that of the previous season and more than 400,000 under the attendance in the inaugural 1913 campaign of the Hempstead club presidency. The major leagues as a whole had fared no better in 1918, each circuit losing about a million patrons from the previous year. Drastic measures were needed to restore the game to good health. To that end, Hempstead and Boston Red Sox owner Harry Frazee proposed the installation of former President William Howard Taft as an all-powerful one-man executive-in-charge of major-league baseball.29 But while the Taft proposition and competing remedies were being mulled on the sports pages, major changes in the operation of the New York Giants franchise were afoot behind the scenes.

Major-league baseball was on the verge of a golden era. The game would enjoy immense popularity in the 1920s, with ballpark attendance skyrocketing and club investors reaping the rewards. But Harry Hempstead did not see this. In January 1919 he saw only hard times ahead, with baseball being no place for the Brush family women and their money. His inclination to sell the ballclub, however, produced a temporary split in family ranks. Elsie Brush trusted Hempstead’s judgment and would do as he advised, while daughter Natalie, although now a young adult, would do what her mother told her. Eleanor Hempstead was another matter. A private woman but fiercely protective of her father’s legacy, Eleanor resisted selling, but outnumbered by her husband, stepmother, and half-sister, ultimately acquiesced.30 On January 14, 1919, Hempstead released a public statement announcing “with many regrets” the sale of the Brush family holdings in the New York Giants. The new club owners were a syndicate headed by Manhattan stock trader Charles A. Stoneham. Giants manager McGraw and New York City Magistrate Francis X. McQuade were small-stake syndicate members and invested as club officers, McGraw becoming vice president and McQuade treasurer, with Stoneham assuming the club presidency. The sale price was generally reported as $1 million.31 Curiously, Hempstead himself retained stock in the club, later going so far as to maintain that he was the third largest shareholder in the new club operation.32

Divested of the responsibility of running the New York Giants, Harry Hempstead remained president of the Brush family clothing business until he retired from that post in 1922. A New York resident for most of the previous decade, Hempstead spent his remaining years in affluent leisure, alternating his time between a Park Avenue apartment in Manhattan and a Westchester County mansion, when not traveling abroad. Hempstead continued active in the affairs of Lafayette College, elected NYC Alumni Association president in 1920, and he served as a member of the college board of trustees until 1936. During these years, Hempstead remained mostly out of public view, except for a brief flirtation with the Giants. Back at franchise headquarters, the Stoneham-McGraw-McQuade management troika had not proved a congenial one, with Stoneham and McGraw even reportedly getting into a fist fight. In October 1922, therefore, credence was extended to published reports that Stoneham was entertaining a buyout offer from Harry Hempstead and former New York Highlanders president Joseph Gordon.33 Believing that they had a first option on Stoneham’s stock in the Giants, McGraw and McQuade raged at the reports and threatened legal action. Evasive nondenials by Stoneham only inflamed the situation, prompting the club president to retreat to Havana until the furor abated.34 In the end, Stoneham would retain his interest in the franchise, serving as Giants president until his death in 1936. By then Hempstead had long since sold his stock in the New York franchise to a former St. Louis Cardinals co-owner named Anderson for a reported $200,000.35

In March 1938 Harry Hempstead suffered a stroke while in his Park Avenue apartment. He lingered for ten days thereafter, dying on March 26 at the age of 69. Following funeral services, he was buried in the Brush family plot at Crown Hill Cemetery in Indianapolis. Survivors included his wife, Eleanor, sons Gordon and John, as well as Elsie Brush and her daughter Natalie Brush Gates. An able but cautious man, Hempstead served the interests of baseball and family diligently, but was risk-averse and lacked the vision required to usher his club into baseball’s oncoming golden age. Compared with others who held the franchise reins, Harry Newton Hempstead left no more than a modest imprint on New York Giants history.

Notes

1 Sources for the biographical details of this profile include the Harry Hempstead file at the Giammati Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York; US Census data (1860-1930), and assorted newspaper paper articles, particularly a sketch of Hempstead by sportswriter Harvey Woodruff, published in the Chicago Tribune, March 1, 1914, and Hempstead obituaries printed in the New York Times, Indianapolis Star, and Indianapolis News, March 27, 1938. Harry’s older siblings were Silas (born 1846), Frederick (1850), Ernest (1851), William (1856), and Minnie (1859).

2 Prior to opening the brokerage firm, O.G. Hempstead was the US collector of customs in Philadelphia.

3 For particulars on Harry Hempstead’s long connection to his alma mater, the writer is indebted to Diane Windham Shaw, director of special collections and college archivist, Lafayette College, Easton, Pennsylvania.

4 According to sportswriter Harvey Woodruff in the Chicago Tribune, March 1, 1914.

5 Little is known with certainty about the first Mrs. John T. Brush, including the status of the Brush marriage at the time of her death in June 1888. Whatever the situation, Eleanor Brush resided with her father.

6 In 1875, delays in the opening of his Indianapolis department store prompted Brush, a dour man with an improbable flair for advertising promotions, to post signs around the city that merely read When? Intrigued shoppers flocked to the store when the premises finally opened, inspiring Brush to employ When as the byword for his store and, later, the Brush clothing corporation.

7 A.R. Cratty, Sporting Life, November 2, 1902.

8 Sporting Life, December 23, 1907.

9 The Brush domestic situation was somewhat awkward. Eleanor Brush Hempstead was born on March 18, 1871, which made stepmother Elsie Lombard Brush, born on November 26, 1869, little more than a year older than Eleanor. Half-sister Natalie Lombard Brush was some 25 years Eleanor’s junior.

10 Among other places, accounts of the Polo Grounds reconstruction are provided in Stew Thornley, New York’s Polo Grounds: Land of the Giants (Philadelphia: Temple Univ. Press, 2000), 63-67, and Noel Hynd, The Giants of the Polo Grounds (New York: Doubleday, 1988), 162-163.

11 The new ballpark was officially named Brush Stadium but, like its predecessors, was almost universally called the Polo Grounds.

12 Sporting Life, November 23, 1912.

13 The sale rumors were headlined in Sporting Life, December 7, 1912, and widely reported elsewhere.

14 Los Angeles Times, December 3, 1912; Sporting Life, December 21, 1912.

15 Undated circa December 1912 Cincinnati Enquirer news item preserved in the Harry Hempstead file at the Giammati Research Center.

16 Lloyd served as New York Giants treasurer and was also a minority stockholder in the club.

17 Sporting Life, January 11, 1913.

18 In his 1923 memoir, McGraw was fulsome in his praise of John T. Brush. Harry Hempstead’s name was not mentioned. See John J. McGraw, My Thirty Years in the Game (New York: Boni & Liveright, 1923).

19 An investment prospectus was delivered to Hempstead at his Indianapolis address, prompting the Giants club president to remark, “What do you think of that for gall?” New York Times, January 23, 1914.

20 Sporting Life, February 20, 1915.

21 Sporting Life, August 15, 1915.

22 Sporting Life, January 1, 1916.

23 Sporting Life, January 1, 1916.

24 New York Times, December 17, 1915.

25 New York Times, January 13, 1916; See also The Sporting News, January 20, 1916.

26 The Sporting News, January 20, 1916.

27 “The National Game,” by H.N. Hempstead, President of the NY Giants, distributed by the National Editorial Service and published nationwide. See e.g., Los Angeles Times, May 6, 1916.

28 At the behest of club president Hempstead, New York Giants players were oft-times dispatched to tutor the Leopards nine. An October 1916 exhibition game between the Giants and the Lafayette varsity drew a campus crowd of 1,500, New York winning 9-0. Diane Windham Shaw e-mail to the writer, September 12, 2012.

29 New York Times, November 24, 1918.

30 This family division was only revealed many years later by Natalie Brush. See Rick Johnson, “The Forgotten Architect of Indiana Baseball,” Indianapolis Star Magazine, May 4, 1975, p. 47.

31 Chicago Tribune/New York Times, June 15, 1919. Later, Giants historians raised the franchise purchase price to $1.3 million. See e.g., Tom Schott and Nick Peters, The Giants Encyclopedia (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing, Inc., 1999), 90. Dominant stockholder Stoneham acquired 1,300 shares in the club. McGraw and McQuade bought 70 shares each.

32 New York Times, October 26, 1922. A process of elimination suggests that Ashley Lloyd, Brush’s old friend and junior partner, must have been the stockholder with the second most shares in the Giants franchise, his holdings falling between those of Stoneham and Hempstead.

33 The Hempstead-Gordon overture was first reported in the New York Sun, October 14, 1922, and pursued thereafter by other baseball news outlets. See e.g., New York Times, October 26, 1922, and The Sporting News, November 2, 1922.

34 The Sporting News, November 23, 1922.

35 New York Times, June 13, 1924.

Full Name

Harry Newton Hempstead

Born

June 25, 1868 at Philadelphia, PA (US)

Died

March 26, 1938 at New York, NY (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.