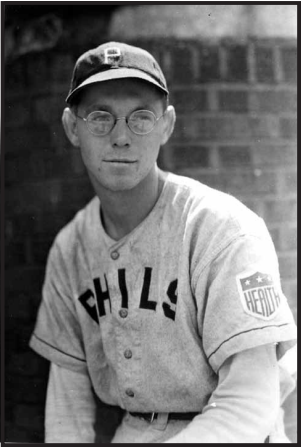

Hilly Flitcraft

For some ballplayers, World War II presented opportunities that probably would not have existed if a large number of players had not been lost to the war effort. For those who had already established themselves as professionals, the war called for a sacrifice beyond those made by others who served: Even those who were fortunate enough to return from service faced the risk of injury or eroded skills that cost them their careers. Hilly Flitcraft experienced both sides of that coin, gaining an opportunity at the start of the war, then paying a price later because of an injury resulting from his work in a vital war industry.

Hildreth Milton Flitcraft, known as Hilly, was born on August 21, 1923, in Woodstown, New Jersey, a rural community across the Delaware River from Wilmington, Delaware, and just southeast of Philadelphia. His parents, Hildreth Milton (who generally went by his middle name) and Edna Crispin Flitcraft, were Quakers who operated a large dairy farm and creamery serving the Delaware Valley. In addition to Hilly, their family consisted of four other boys and a girl.

Hilly showed an interest in baseball from a young age. His great-uncle, a semipro ballplayer, gave him a ball and glove when he was 5. As a young teenager, Hilly used them to emulate his idol, Cleveland Indians pitcher Bob Feller, who was known for having honed his skills throwing a ball through a hole in a barn. Flitcraft later told an interviewer: “On the dairy farm where I was raised, we had a milk house with a cinder block wall. I practiced throwing at specific cinder blocks with various pitches.”1 By the age of 13, he was playing ball with adults in the college-level Salem County League.

Flitcraft attended the local schools in Woodstown, emerging as a multi-sport athlete in high school. In addition to baseball, he earned varsity letters in football, basketball, and track (pole vault). He earned local honors in football and basketball and All-South Jersey honors in baseball. He pitched and played first base and the outfield. All the while he continued to work on the farm, often getting up at 4 A.M. to deliver milk before school, and then completing another run after classes and sports were complete.

After graduating from high school in 1940, Hilly enrolled at the New Jersey Agricultural College, part of Rutgers University. As a 17-year-old he played on the freshman baseball team. The next year he made the varsity squad. But with upperclassmen occupying most of the pitching rotation and outfield spots, Hilly’s playing time was limited to a handful of games. In April 1942 he got a start in center field behind senior Jim Perkins against Manhattan College. Perkins shut down Manhattan, allowing no hits and only one walk. Although he didn’t get a hit, Flitcraft contributed to one of Rutgers’ two runs: With runners on second and third, he hit sharply to the Manhattan shortstop, who could not handle the ball cleanly, allowing a run to score. In another game, Flitcraft’s defensive play made him a hero. Trailing Lafayette 3-0, the Scarlet Knights fought back with four runs in the eighth inning. In the bottom of the ninth, a Lafayette hitter drove a ball deep to Flitcraft’s position in right. He sprinted out and snagged the fly in the web of his glove, saving the game by preventing a likely home run.

In the summer Flitcraft returned to play in the Salem County League. Also on the team was his former high-school baseball coach, Woody Litwhiler, who noticed Hilly’s increased speed and improved curveball. Woody’s brother, Danny Litwhiler, played with the Philadelphia Phillies.2 After seeing Flitcraft play, Danny arranged for him to try out with the Phillies. The audition initially led to the Phillies inviting the bespectacled lefty to work out with the major-league club for a couple of weeks and pitch batting practice during a swing through the West, which at the time meant Chicago, St. Louis, Pittsburgh, and Cincinnati. Flitcraft also pitched for the Phillies in two exhibitions. The first, against the Phillies’ Class-B team in Wilmington (Inter-State League), was not very successful – he was replaced in the fourth inning after yielding two runs on six hits. He showed improvement in the second game, scattering four hits and pitching five shutout innings against Harrisburg (also of the Inter-State League). After the road trip, the Phillies signed Flitcraft to a two-year contract for $250 per month. The contract also allowed him to continue his studies at Rutgers and rejoin the Phillies when the school year ended in early May.

Before appearing in a major-league game, Flitcraft started another exhibition, this one an August tilt against an Army team from Fort Dix, New Jersey. It didn’t start well, with three Fort Dix runs in the first, but Flitcraft shut the Army team down the rest of the way. He also had a hit, leading to the Phillies’ first runs, and started a 1-2-3 double play. The Phillies wound up winning when the deciding run came home on the back end of a double steal.

Flitcraft’s major-league debut came on August 31, 1942, in Cincinnati. With the Phillies riding a six-game losing streak, manager Hans Lobert called on him with the Phillies trailing the Reds 7-1 in the seventh. Lobert wanted the bespectacled southpaw Flitcraft to take on right-handed hitters Frankie Kelleher, Frank McCormick, and Eric Tipton. He struck out McCormick, an eight-time All-Star, and retired the others without allowing a ball out of the infield, the only Phillies hurler that day to work a clean inning.

It might appear unusual from today’s perspective for the Phillies to bring a player with no real professional experience to the majors. However, the Phillies were already short on talent, having finished last in the previous four seasons and five of the previous six. To make things worse, the war hit them harder than most, with 17 players lost to military service before the start of the 1943 season. In that environment, any player with promise was worth a chance.

Flitcraft’s second appearance was not as successful as the first. With the Phillies trailing 10-3, he started the ninth inning against the Boston Braves in the first game of a September 6 doubleheader at Philadelphia’s Shibe Park. He faced five batters and retired only one while yielding two hits, two walks, and a wild pitch. The few Phillies fans in attendance were probably already dispirited before Flitcraft entered the game because of the score and the fact that their team had popped into a triple play earlier in the day. Flitcraft rebounded somewhat in his final appearance of the year, on September 17. With the Phillies trailing the Cubs 6-0, he was brought in in the seventh inning in relief of Andy Lapihuska, another young rookie from South Jersey. This time, Flitcraft went two innings, allowing one run on four hits while recording a strikeout.

While getting his feet wet in the majors, another concern arose for Flitcraft. He had turned 19 that August, making him eligible for the draft, and his family were Quakers who were morally opposed to war. However, the family dairy farm was considered a vital war industry, and working there would earn Flitcraft a draft deferment.3 So, before the start of the 1943 season, Hilly officially retired from baseball and returned to the farm in Woodstown.

In the spring of 1945 Flitcraft took himself off the voluntary-retirement list and went to Wilmington, where the Phillies and their farm teams held a combined spring training because of wartime travel restrictions. When he didn’t make the Phillies roster, Flitcraft asked to be assigned to the Class-B Wilmington Blue Rocks instead of the higher-level team in Utica, New York, so he could be close to home. The Phillies traded his contract to Wilmington for that of third baseman Don Hassenmayer.

Flitcraft recalled the 1945 season as his favorite in pro ball, and it was his most successful. He won his first five starts on his way to a 15-4 record. He was selected for the league’s all-star team, and although he didn’t pitch in the game, he was sent in to pinch-hit. His best game of the year came on a day tinged with personal loss: Before a scheduled start on June 29, Flitcraft was informed that his mother had died. He went out that night and pitched a two-hit shutout in which he fanned seven Lancaster hitters. Then he went back to Woodstown for the funeral. Other times, his teammates’ bats picked him up. In one notable game against Hagerstown, Flitcraft gave up 11 runs in a three-inning stretch. Luckily for him, his side had put up 12 tallies in a single inning earlier in the game, on their way to a 33-13 victory. Flitcraft did his share with the bat, going 3-for-6 with a triple and three RBIs in that game.

Playing so close to home, Flitcraft continued to help out on the dairy farm. One day in May he was changing a tire on a tractor when he injured his back, resulting in a bulging disk. The injury did not at first hamper his performance on the mound. By mid-July, however, doctors advised Flitcraft to take a break from baseball, so he sat out about two weeks. He returned to action, but was later admitted to Cooper Hospital in Camden soon after his all-star appearance in August. Doctors initially decided Flitcraft needed an operation, but it was postponed until after the season. He was back in action a week later, starting the first game of a doubleheader.

Flitcraft finished out the season but was not initially expected to participate in the playoffs. However, when Wilmington’s ace, 22-game-winner, George Estock, was lost for the semifinal series due to jaundice, Flitcraft stepped in to take his place. After sitting out the first game, a Wilmington victory, he got the call to start in Game Two, Hilly held Allentown to three runs over eight innings, matching the offense put up by his teammates. The visitors got to him in the ninth, though, with a five-run rally that sank Wilmington. Allentown also won the next two games, putting Wilmington on the ropes. In the fifth game of the series, Flitcraft hit three batters but struck out eight in a 10-6 win. Then his teammates lost the next game, ending their season.

Doctors operated on Flitcraft’s back in December 1945. The following spring, he attended spring training but was still not feeling up to par. A second operation was prescribed; that took place in June and kept him off the field for all of 1946. The second operation was more successful than the first, but Flitcraft’s back bothered him the rest of his life.

The spring of 1947 saw Flitcraft back in spring training. Initially tabbed for the Phillies’ top farm club, in Utica, he was roomed with a rising player from Nebraska named Richie Ashburn. With his back still causing him problems, Flitcraft wound up being sent all the way down to Class-D Carbondale (Pennsylvania). His results were respectable, but he was effectively done for the season by the end of July, because of his back problems. In his best game of the year, he held Bloomingdale (New Jersey) hitless for eight innings before settling for a two-hit win.

After being released by the Phillies, Flitcraft returned to Rutgers for the spring 1948 semester. However, he was offered another chance at baseball. This time, the Philadelphia A’s wanted him to play first base for their Class D entry in Portsmouth, Ohio. In a doubleheader on June 8, he had his best day of the season, going 7-for-8, with five RBIs on two doubles, a home run, and two stolen bases. By August he was batting .327, but he broke a finger, catching it in an opponent’s uniform in a play at first base. He thought his season was over. However, the A’s asked him to fill in at their Class-A team in Lincoln, Nebraska, where first baseman Lou Limmer had suffered a spinal injury. It would be Flitcraft’s last role in professional baseball.

When the season ended, Flitcraft again returned to Rutgers for good, completing his degree in 1950. While there he met Janice Devine, a local girl and student at Douglass, the University’s women’s college. They married in 1950 and had one daughter, Dana.

After graduation Flitcraft spent several years in the insurance business in New Brunswick, New Jersey. In 1956 he became a food marketing agent for the Cooperative Extension Service at Rutgers. There, he helped teach 4-H club members about purchasing and preparing beef and eggs, taught marketing to farmers, and wrote an educational pamphlet on food costs. In 1961 he returned to Woodstown to work in a local insurance agency. He later bought the agency and operated it until his retirement. In 1993 he was inducted into the South Jersey Baseball Hall of Fame.

Flitcraft remained an active supporter of youth sports throughout his life. In New Brunswick he and Janice organized a local swim club. When he returned to Woodstown, he helped organize the local Little League, becoming the league’s first president. He was later instrumental in building the league a new field as a member of the Rotary Club.

Upon his retirement from the insurance business in 1991, Flitcraft moved to Colorado to be closer to his daughter and her family. He died of complications from surgery in a hospital there on April 2, 2003.

Later in life, Flitcraft shared his perspective on his ballplaying days. “At the time, it was just something we did for a few months a year,” he said. “It was almost a nonpaying job. But it was a thrill to be there … getting paid to play baseball.”4 Hopefully there are still former players who can look back on their playing days with such affection and respect for the game.

Sources

The author wishes to gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Mr. Flitcraft’s daughter Dana Flitcraft, who provided invaluable assistance, including copies of her father’s news clippings.

Beyond those sources cited individually, information for this biography was derived from Flitcraft’s player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame’s Giamatti Library, as well as articles in various issues of the following publications:

New York Times

Philadelphia Inquirer

Scranton (Pennsylvania) Times

The Sporting News

The Targum (Rutgers University)

Trenton (New Jersey) Times

Wilmington (Delaware) Journal

Notes

1 Joseph C. DeLuca, Diamond Heroes of South Jersey (Bridgeton Antiquarian League, 2000).

2 Danny Litwhiler’s SABR biography can be found at sabr.org/bioproj/person/b8c36843.

3 For further discussion of professional baseball during the World War II era, see David Finoli, For the Good of the Country: World War II Baseball in the Major and Minor Leagues (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2002).

4 Mark Wilgus, “Flitcraft Inducted Into Hall of Fame,” undated clipping from the Giamatti Library’s player file on Hilly Flitcraft.

Full Name

Hildreth Milton Flitcraft

Born

August 21, 1923 at Woodstown, NJ (USA)

Died

April 2, 2003 at Boulder, CO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.