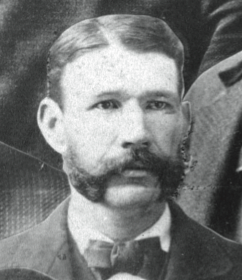

Hugh Daily

A rookie at the age of 34, he beat the Chicago White Stockings 10 consecutive times in the heart of their dynasty, struck out 483 batters in a single-season, and earned the reputation as one of the first power pitchers in the history of baseball. Hugh Ignatius “One-Arm” Daily did all that with the greatest handicap a baseball player could have: an uncontrollable temper. Daily’s horrific, cuss-laden in-game outbursts towards the opposition, umpires, fans, and teammates reduced what should have been a superstar major league career to six short years of bitter memories, embarrassments, and burned bridges. No team ever re-signed him for a second season.

A rookie at the age of 34, he beat the Chicago White Stockings 10 consecutive times in the heart of their dynasty, struck out 483 batters in a single-season, and earned the reputation as one of the first power pitchers in the history of baseball. Hugh Ignatius “One-Arm” Daily did all that with the greatest handicap a baseball player could have: an uncontrollable temper. Daily’s horrific, cuss-laden in-game outbursts towards the opposition, umpires, fans, and teammates reduced what should have been a superstar major league career to six short years of bitter memories, embarrassments, and burned bridges. No team ever re-signed him for a second season.

Of course, this was not the handicap Daily was known for. Around 1861, it was said, the 13-year-old Irish immigrant was shot through the left wrist with a loaded musket in backstage horseplay at Baltimore’s Front Street Theater, a Union armory during the Civil War. “One Arm” Daily was in fact one-handed, a condition serious enough to have kept the 25-year-old off Baltimore National Association franchises in 1872 and 1873. Relegated to 10 years of sandlot and semi-pro play, Daily made a name for himself in Baltimore by 1875. The family resided at 1300 Valley Street from the 1870’s if not earlier. Parents Thomas and Rose brought Hugh, brother Thomas, and sisters Bridget and Rose from Ireland around 1851. Father Thomas, a common laborer, escaped the potato famine and worked this tough life well into his seventies.

Daily saw action each year on a variety of teams playing second base, right field, or pitching. When no team was available, he organized his own team – often called the Acmes – and captained it batting lead off. A typical year for Daily saw play into November. In the second half of 1876 Daily went 20-3 for the Baltimore Quickstep and loaned himself to the Philadelphia Arctic for an occasional start. In the Spring of 1877, four Quicksteps – “the champion team of the South” – traveled North with veteran Charlie Sweasy and joined the roster of a rebuilt independent team in Providence, Rhode Island. Among these Quicksteps was Daily.

For a small city team scratched together by the donations and subscriptions of about 200 citizens, Providence’s year was terrific. They finished with a 33-35 overall Record that included a win hosting champion Chicago and two hosting Boston and impressed enough to earn a 1878 National League spot. But Daily shared in none of the spoils. In 12 season-opening starts he won four of 10, beating only the lowliest opponents: Brown University, Holy Cross, and two traveling teenager teams from Boston. Against nationally rated opponents Daily was winless and wild. On June 6th, losing 0-4 in three innings to Syracuse’s Harry McCormick, Daily was yanked and switched places with the right fielder. He robbed Pete Hotaling of a triple with a backpedaling one-handed stab, but would be given only one more chance to impress. Two weeks later Daily got that chance against Boston’s “Our Boys” teenagers. He didn’t get past the third inning and was unceremoniously released.

The experience brought to the forefront the Daily dilemma. Daily was in that last generation of pitchers who could only be “relieved” by switching positions with someone else on the team, usually the right fielder. Free substitutions from the bench or bullpen would not come until 1890. Yanking Daily from a poor start meant putting a gloveless, one-handed, fielding liability somewhere on defense. For example, on June 15, 1887, Daily pitched a nine-inning complete- game loss after giving up nine runs in the first inning. Managers resisted relieving Daily throughout his career no matter how hard he was being hit. As a result, Daily holds the national league record for percentage of career starts completed (96%).

By adapting to his one-handedness early, Daily honed his fielding skill to a remarkable degree using a unique style. He played with a protective leather “stud” strapped to his left stump and trapped most throws and grounders against it. A certain area of the harness – which he referred to as “the hollow” – could stop hard hit balls pain free. For pop ups and flies he preferred to use a stab of his good right hand, a low percentage, strategy that failed pitifully if the ball had any spin.

After being released by Providence, Daily spent the early part of the summer pitching in Washington for the young Astoria team and led them to a surprising victory over the older and more professional Washington Nationals. He also gave the first on-field demonstration of a curve ball that citizens of Washington had ever seen. “High arm pitching” – release point still below the hip – was in full swing and umpires could do little to check the fan-approved fad. With each passing year Daily’s arm was creeping up.

One month later he was back in Baltimore, organizing teenagers into his very own “Amri” team. After his catcher, 19-year-old Pennsylvanian Charlie Delphy, drowned taking a swim in Baltimore’s inner harbor, the “Amris” vanished and Daily pitched and played middle infield for the “Baltimores”. Then he appeared with the “Marylands” and the “Excelsiors” in October. Switching teams for a buck was second nature to Daily and Baseball was booming in Baltimore. The city opened many new ball fields during this time, including a state-of-the-art field in Johnson Square, right across from the Daily residence.

In 1878 it looked like the end for Daily. He pitched with the Baltimore Waverly along with 42-year-old Dickey Pearce, whom he had met in Providence, and little Bobby Mathews, a fellow Baltimorean oft-suspended by the Worcester team. Five years younger and nine inches shorter than Daily, Mathews also seemed washed up after 131 National Association wins. That’s when fate came into play. Perhaps because the theater was the scene of Daily’s childhood accident, it was a theater manager, Ormond Butler, whose actions paved the way for Daily’s return to professional ball. Thinking there would be little difference managing baseball as opposed to the theater, Butler reorganized the independent Washington National franchise, stocked it with the best available talent, and coaxed some of the better teams in the country to travel south for games. On the way, nearly all of these teams played games in Baltimore.

Against Pittsfield, New Bedford, Utica, Syracuse, and others Daily was winless in his first 14 starts before finishing the year with a 5-20 record. That same year East Coast free agents Bill Shettsline, Fergy Malone and Tug Arundel began gravitating to Baltimore. The buzz of activity continued into 1879 as Washington signed more stars and joined the National Association. Daily stayed a workhorse for the Baltimore “Independents” but loaned himself out to Philadelphia teams whenever the chance came up. In Mid-August he lost two 1-0 games to Rochester on consecutive days. On September 23, pitching for the traveling “Philadelphia’s,” Daily had a no-hitter spoiled by Joe Battin. Tension on the Independents in August, because Daily alienated his own teammates with public criticism after they made errors, led to a revolving door of players on the club. On August 19 a new Independent team hit the field “keeping only Daily from the old club,” and Daily found himself with the greatest gift a pitcher could have: a star catcher.

Like Daily, Tom Deasley was from Ireland and had a temper. With back and forth swearing the two started a love-hate relationship that would see them win games for four different franchises. Deasley’s athleticism allowed Daily to push the envelope for pitch speed. Daily was no longer described as a pitcher but a thrower, a description which implied he would not have been allowed to pitch in the National League where pitches released from “over the hip” were prohibited.

Late in 1879, Baltimore attracted a former National League manager to take the reins of the club. “Hustling” Horace Phillips was a fast talker who had previously managed the Troy Nationals. For 1880, Phillips entered Baltimore into the National Association, along with Albany and Washington, and set about to make Baltimore top ranked. He brought a distinctive Troy flavor to the club with outfielder Jake Evans and first baseman Dan Brouthers. Lou Say, Lew Dickerson, Bill Smiley, and John Richmond were among others who brought along National League or National Association experience.

Phillips billed Daily as the star and flooded Baltimore with flyers that featured a woodcut of “America’s only one-armed pitcher.” But Daily continued his old ways, cursing out his new teammates after they made errors. He was effective using a “regular overhand throw which could not be allowed in a league game.” He beat Providence and their ace Monte Ward 5-1 three days before their National League opener. On May 10, Baltimore opened their National Association season hosting Albany at Newington Park before a packed house including many ladies. Baltimore made errors – 23 in all – behind the seething Daily, but entering the bottom of the ninth still clung to an ugly 16-11 lead. It got uglier. A final wave of misplays inthe last frame allowed six runs to score for a loss, 16-17. During this collapse Daily let loose a booming fusillade of cuss-laden epithets that stunned the fans into a shocked silence. Team directors assembled an emergency meeting and suspended Daily one month: ostensibly for “crookedness”; in reality for cursing.

For the duration of Daily’s suspension, Baltimore signed big Morrie Critchley who had a 17-game winning streak for Albany the previous year. But Critchley’s arm was shot. When Daily returned, Baltimore had sunk to third place in the three-team league, seven players signed a petition to oust the one-armer, and Phillips had quit: angry at the meddling Baltimore directors. Back in the pitcher’s box Daily was dispirited. Surrounded by players who despised him, he could win but three of 10 starts despite a 1.11 ERA. He also lost to the Yale University nine. Daily’s future, once again, looked bleak.

While Daily was losing Phillips hustled himself into the management of the moribund Rochester “Hop Bitter” franchise. He revamped the lineup and entered the team as a fourth member of the National Association. On June 9th the “Hop Bitters” debuted with an eclectic lineup of available talent which included infielders Levi Meyerle and Steve Brady, and utility men Jackie Hayes and Bill McGunnigle. Most impressive was Phillips’s decision to go with a two-man pitching rotation – a strategy made popular that year by the Chicago White Stockings. Within 24 hours Phillips signed pitchers Stump Wiedman off the campus of the University of Rochester and veteran left-hander Bobby Mitchell off a Cincinnati semi-pro team. Phillips also signed their catchers: Tommy Kearns and Buck Ewing: two unknown, baby-faced, 20-year-olds.

When Rochester played at Baltimore on June 25 Phillips had revenge on his mind. He made deals with four of his old Baltimore players to jump ship and sign with the “Hop Bitters”. Before the National Association could rule against Rochester on Monday, Baltimore ownership immediately “threw up the sponge” and disbanded the team. Dan Brouthers, Billy Hawes, John Richmond, and Aaron Clapp became Rochester property. Two weeks later Mitchell was released for being wild, and Daily and Deasley joined the club.

In eight weeks with Baltimore, Daily went 7-16 in 23 starts with 189 innings pitched. He allowed 180 hits, 45 walks, and struck out 70. In championship games his record was 3-6. He had a shining 2.04 ERA overall, but his total runs per game allowed, including runs scored on errors, was 6.61, about two and one-half runs higher than would be expected. Poor grounds keeping or having a weak fielding team could explain such a difference. Daily seemed to be improving with each start.

In eight weeks with Rochester, alternating with Wiedman, Daily’s numbers got even better. In 17 starts he logged 145 innings with 110 hits, 28 walks, and 40 strikeouts. His ERA dropped to 1.09, and his total runs-allowed was a more reasonable 3.66. His record was 7-8. The problem wasn’t Daily’s team anymore, it was his league. Three weeks after Baltimore disbanded, Albany did the same. Rochester and Washington, the only two teams left in the Association, played each other 15 times by Labor Day to diminishing fan interest. Both managers, Phillips and Washington’s Jim Gifford, quit their teams. In July a three game series was moved to Springfield, Massachusetts, and in August they moved their “pennant race” exclusively to Brooklyn. A six game round-robin tournament between Rochester, Washington, and a new Brooklyn team was won by Rochester, August 24, and they were awarded a set of silverware.

Washington was the superior team, and Daily matched up nine times against their ace, George Derby. Daily won five straight games in Brooklyn, but any harmony between Daily and Deasley became strained when Deasley broke Daily’s sawed-off toothpick bat beating back a rowdy fan. Phillips used Buck Ewing to catch Daily in spots before Troy stole Ewing and Brouthers, August 25. Forced to play together, Daily and Deasley’s animosity erupted in Washington, September 1st. Holding a 1-0 lead in the top of the eighth inning, Daily gave up an opposite field single to weak hitting Jack Lynch, which set up first and third and nobody out. Deasley fired the ball back

to Daily, hard.

“Arch ’em Tom! Arch ’em!” Daily yelled, “They crack against me stump and give me a twitch!”

But Deasley continued returning the ball hard and Daily motioned for his catcher to jog out to the pitcher’s box. As Deasley leaned into Daily for a whisper, Daily swung his stump around cracking Deasley square on the jaw. Deasley dropped his fielding gloves and stormed toward the clubhouse in center field, where playing manager Billy Hawes calmed him down. Play resumed, but two quick Deasley passed balls allowedboth runners to score, and the game was lost.

Two days later the Rochester team traveled north toward an uncertain end-of-season exhibition home stand. At Jersey City the train was met by a short, fast-talking, man in a derby hat named Jimmy Mutrie. The ex-utility player had spent most of August folding cardboard in a Manhattan box factory. He had managed the failed Brockton, Massachusetts team earlier in the year. He told them about an idea he had for a new New York team which would go onto the Union grounds to challenge Billy Barnie’s new Brooklyn squad and National League teams in October when the NL schedule ended. Five Rochester players got off the train.

Daily, Deasley, Kennedy, Brady, and Hawes, joined Oscar Walker, Joe Farrell, Tom Esterbrook, and veteran Candy Nelson on a New York team dubbed the “Metropolitans.” Bobby Mathews, back from California, was originally slated to be the team’s pitcher, with Hugh Daily the regular shortstop. But Mathews spent time unsuccessfully negotiating a contract with Troy and passed on the New York offer. On Wednesday, September 15, Jim Mutrie’s vision of a strong New York team, backed by the dollars of John B. Day, took the field with Hugh Daily the starting pitcher. They beat Billy Barnie’s Brooklyn squad 12-0.

New York rolled to a 9-1 record, outscoring opponents 92-25. Barnie, conceding New York territory to the Mets, quickly moved his Brooklyn team to Jersey City. Fans, who had not seen a New York team with a national reputation since 1876, swamped Brooklyn’s Union grounds in Williamsburg and ferried it to Henderson Street in Jersey City to cheer them on. On September 20, the Mets played Barnie’s team on Hoboken’s Elysian Fields and Daily tagged Tip O’Neill – the future slugger — for an eighth-inning home run. Mutrie wanted a city field to call his own. Barnie recommended a parcel of land at Fifth Avenue and 110th Street used exclusively by the New York Polo Club, at that time away in Rhode Island competing for a national championship.

On Wednesday, September 29, 1880, the Metropolitans hosted the Washington National Association team at the hastily converted Polo Grounds, the first professional baseball game ever played on Manhattan Island. Hugh Daily spun a six-inning four hitter over Jack Lynch winning 8-3 in front of 2,500 baseball-mad citizens. Daily’s single in the fifth inning snapped the tie and became the game-winning hit. Behind Daily, New York swept three packed games in three days while bleacher construction moved along at a fever pitch.

On October 1st, the National League schedule ended and just as Mutrie and Barnie had predicted, all the major league teams wanted to play post-season, exhibitions in New York. New York won five of 16 games and a carnival atmosphere dominated. When Daily’s arm got tired, opposition NL pitchers loaned themselves to the Mets including Curry Foley from Boston and John Ward from Providence. Big money games continued until October 23, but they did so without Daily. On October 11, in the middle of New York’s big splash, Daily walked off the mound in the second inning of a game against Troy, boarded a train for Baltimore, and was lost for the year. A fan had insulted him. The real reason might have been a week-long city fair in hometown Baltimore celebrating that city’s 250th birthday.

All told Daily finished 1880 with a 24-29 record, 53 complete games, 460 innings, And a 1.29 ERA. He gave up 395 hits, 85 walks, and struck out 170. Despite the increasing level of competition, Daily got better by the month. When New York opened the 1881 season with a practice game against Manhattan College; Daily was in the box.

The record profit for any baseball team in a single season was set by the 1881 New York Metropolitans who, it was estimated, cleared $30,000. As an independent professional team, New York was able to schedule only the opponents they wanted to play. Most of the Mets games were at home, and the sale of alcohol was permitted on the grounds, adding to the profit potential. For days when no National League opponent could be scheduled, the Mets created their own league: the Eastern Championship Association from which teams came and went. Variously, it was a five or seven team “league” that acted as a clearing house for the pool of players unsigned by the dissolution of the National Association. Albany and Paterson fielded teams. John Kelly, who made a name for himself as a playing manager for Manchester in 1878, formed a second New York team. A third New York team, the Quickstep, debuted June 14 and lasted nine games.

The Mets were the darlings of New York and the one-armed Hugh Daily was the star attraction. The record for games played in a single season – 138 by Harry Wright’s 1877 Boston Nationals – was shattered by the Mets who played 150 games. Daily started nearly half. In 73 starts he went 35-35 with 68 complete games and a whopping 614 innings. He allowed 564 hits, walked 95, and struck out 346. His ERA was a spectacular 1.57. Without pitching restriction he threw as hard as he could from any angle he wanted and visiting National League hurlers followed suit. Daily’s

new weapon was the strikeout.

Hugh’s first career 10-strikeout game – against a strong opponent – came April 23 against Providence when he beat Monte Ward 5-4. On May 9 he had a no-hitter against the Philadelphia Athletics broken up by Jud Birchall in the ninth inning. The next day he had another no-hitter going against them after four innings but switched to right field when the score became too lopsided. His season high for strikeouts was 16, on August 6, also against the Athletics, a team that would go on to join the American Association the following year. Thirty-five of his starts were against National League teams against whom he logged 280 innings with an ERA of 2.54. He beat each NL opponent at least once and was especially effective against Buffalo and Worcester. His overall record against NL teams was 10-23. It was reported that Daily was one of the best pitchers at holding base runners on. He had one of the shortest motions of the era with a planted back foot – other pitchers took steps – and he used to lie flat on the ground when his catcher threw to second base.

Daily had his troubles and missed about 10 starts due to sickness. With a third inning 8-1 lead over the Detroit Nationals, June 3, Daily got soaked and sick as a rainstorm canceled the game and confined him to his bed for three weeks. He also had to learn to pitch to a new catcher: Jerry Dorgan. On October 7 of the previous year Harry Wright snatched up Deasley for Boston. On April 4, 1881, a throw by Dorgan on a stolen base attempt nailed the prostrate Daily right in the ribs. Trapping balls with his bare hand against his stump, Daily was effective catching grounders and flies. Little pop ups with spin were a huge problem. In the 11th inning of one Boston game, April 30, Daily jumped in front of first baseman Dude Esterbrook and botched a Jack Burdock pop up with an attempted back hand stab. Burdock later scored and the game was lost.

Daily covered his stump with leather and secured it with straps. He leaned in to each batter menacingly: cussing in his Irish accent, rolling the ball along his stump. Prickly muttonchops concealed his lips and small, beady, dead eyes came out atop his slender six-foot-two frame. He used a momentum building double motion – like a windmill – the second arm swing becoming the pitch which coincided with a quick stride to the plate without taking steps. When “back foot planted” became a pitching requirement for good in 1886, Daily was one of the few pitchers who didn’t need to adapt. At any moment, even after he started his delivery, he could whip a throw to a base to catch a baserunner. He signaled his own pitches to his catchers but lost to Yale again, on May 11, when he mixed up his own signs. The winning run scored in the ninth inning on

a wild pitch.

It seemed, in 1881, that Daily had a twentieth-century fastball and a twentieth-century curve: unfortunately, he had nineteenth-century catchers. Many, if not all, suffered hand injuries catching the one-armer. Only Deasley ever lasted 50 games for him. Often players from the field would volunteer to squat behind the plate for a stretch of games just to give their regular catcher a break. Daily ran through seven catchers in 1881 including John Kelly, loaned to the team for a game, and future big leaguer Jackie Hayes and veteran John Farrow.

Daily’s nasty disposition did not improve. A crotchety figure in nearly every start, he had to be switched to right field against Washington, on May 26, when he lost his composure with the umpire’s calls. The ump was Ormond Butler, the old Washington manager. In late June, Butler reportedly intentionally took a game from Daily just to spite him. But Daily lashed out at more than just umpires. On August 4, Daily lost to Albany when he cut in front of shortstop Lou Say and muffed a ball in the ninth inning. In the clubhouse he threatened to kill the a baseball reporter if the play was harshly reported.

The New York Herald called Daily “The inveterate growler”. For the rest of the year he received cold press in New York and was no longer mentioned as “the famous one-armed pitcher”. He received a rare accolade after a 7-4 win hosting Chicago, October 1, when he was so dominant that Chicago president Bill Hulbert ran on the field mid-game to lecture Cap Anson. “Masterful” the New York Clipper wrote of Daily. But such performances could not save him. As September turned to October New York openly searched for an 1882 pitcher, settling finally on Jack Lynch who owned a bar near the grounds. Daily returned to Baltimore unsigned but he had reason to be hopeful: six American Association teams were to be created from scratch that winter. Alas, all six passed on Daily, even the team from Baltimore.

Once again, it could have been the end for Daily. His talent had never been great enough to offset demeanor both disgraceful and uncouth. Yet once again, the planets lined up and an opportunity presented itself to the one-armed pitcher.

The advent of the two-man pitching “rotation” was a “bottom up” strategy. The teams with the weak armed pitchers were the first to adopt the strategy; the teams with the strongest pitchers were the last to adopt the strategy. Second place Buffalo with Pud Galvin, the strongest pitcher known to baseball, tried to win the 1881 pennant down the stretch by pitching him alone. But after beating Chicago on September 8, and pulling Buffalo to five and one-half games back with 14 to play, Galvin’s arm became useless. He could win but one game of his final eight, and left fielder Blondie Purcell had to pitch the last four games of the year. When Buffalo realized their roster needed a second pitcher, the pool of available talent had evaporated.

Daily, pitching for minor teams, had beaten the Buffalo Nationals three times. Buffalo captain Jim O’Rourke signed him and announced, “I have batted against Daily, and he is the most perplexing pitcher I ever saw. His delivery is rapid and his curves intricate and peculiar.” The only Buffalo victory against Daily came late in 1881, on two seventh-inning runs that scored on shortstop Lou Say’s errors. Buffalo signed Daily, and for the third time in his career Daily joined a team on which Dan Brouthers starred.

Daily’s April exhibition starts were not impressive. In his first two efforts in Pittsburgh he was moved to shortstop mid-game when NL umps disallowed his high release point. He lost his composure, and the Pittsburg Post called him a “baby of the most colicky kind.” Nevertheless, O’Rourke used Daily opening day hosting Chicago in front of 1,500 fans, a number that included several ladies on a dark and drizzly day. With a new catcher named Tom Dolan, Daily walked three in the first inning and each runner scored. But Buffalo slugged back with Daily cracking a well-received rbi single in the third inning for a 6-3 lead and an eventual 7-5 win.

Daily opened the season 8-4, Galvin 2-6. Unfortunately, on June 3 Daily complained of a sore arm. After that O’Rourke could never count on Daily to pitch a given game. In Troy, June 10, Buffalo had to borrow pitcher James Burke from the Attleboro “Meteor” team. Burke would later star with the Boston Unions, but in this debut he was slaughtered, and Buffalo dropped to seventh place. The team was reeling with catcher Jack Rowe and outfielder Hardy Richardson at shortstop and second base, respectively, in a failed O’Rourke experiment to bring more power to the starting lineup. Buffalo was under .500 till August.

On May 15 Dolan begged off Daily duty, and third base veteran Deacon White volunteered to catch the one-armer. In their first two games together they beat the Chicagos 6-2 and 9-4 on a Wednesday and a Thursday, shutting down Chicago’s running game. Jack Rowe started catching Daily in July when Daily stopped the Chicagos again twice in a row, 5-4 and 4-3. Chicago center fielder George Gore used to play the shallowest when Daily batted: right behind second base. In the first July win over Chicago Daily cracked a ninth inning double over his head and scored the winning run. Jim White’s run scoring triple – also in the ninth inning – four days later secured Daily’s fifth straight win against the champions. Weak armed and pitching .500 ball, Daily nearly broke the ring finger of his only hand and mashed other fingers swinging at an inside Wiedman pitch, July 24. Not being able to feed himself, Detroit fans passed the hat and gave him a collection of $65. Daily made four more starts winning only one: a Worcester game, 13-9, two weeks later. That’s when the Buffalo Courier reported that a clique of players were laying down behind Daily to get him released. From then on O’Rourke only used him primarily in exhibition games. He lost to his old New York Mets, on August 22, 9-10, when Candy Nelson scored in the bottom of the ninth on a play in which he had been obviously tagged out by Dolan. He also lost the next day, batted out of position in the first inning at Philadelphia. When Buffalo went north to Providence, Daily went south to Baltimore. The Courier did not mention the clique against Daily when it reported his sore arm in late August: “It is doubtful he will ever play ball again.”

The oldest pitcher in the majors, Daily would easily have been considered the NL’s rookie pitcher of the year if such an award existed. The book on him was that he was a curve ball pitcher – his curve called a “drop” – and that you could hit him early in a game, before he warmed up, or late in a game when his arm got tired. He was a high arm thrower in the days when such a description was offered despairingly. But in this regard he was ahead of his time. Very soon all of baseball would allow such a style. In fact, in 1878 Bobby Mathews copied Daily’s throw, double motion and all, as the two played together in Baltimore. Late in 1882, Pud Galvin did the same in August, and his curve ball exploded using Daily’s “shoulder throw.” Both pitchers benefited from copying Daily’s style.

Swarthy and dirty-looking scowling and menacing, and with a greatness both untested and unproven, Daily was signed by Cleveland the day before Christmas, to alternate in a two man rotation with another Irishman: the big, blonde, horse-gambler Jimmy McCormick who was the winningest pitcher in the National League’s short history. The two would lead Cleveland to a charmed season of a near championship. After shaking hands with Chester Arthur in the White House, the team traveled north in April running up a 14-0 Spring training record along the way. They opened the championship season with an 18-9 record, bumping Chicago from first place, June 11.

With a new superstition of never speaking on game day before his first at-bat, a quieter Daily reveled in the mix. Fans and management seemed to adore him, and no player rebellion against him was reported. Team treasurer George Howe designed and built a special wire protector for Daily’s stump and Daily became “a favorite with the spectators who are generous in applauding his good work.” Daily refined his delivery with “more showy tricks than anybody who stands in the box.” On the downside, the Cleveland Plain Dealer reported that when Daily pitched “a large sized hole in the Cleveland field was disclosed.” Daily tried hard to make up for this one deficiency. He covered first base on hits to the right side, and waved his fielders to the right and left. He liked his catcher “close behind the bat” for steadiness yet was hurt by being assigned a poor catcher in this regard: Cal Broughton. Broughton was signed specifically for Daily but caught only three games before begging off.

Doc Bushong was the next in a line of terrific catchers for Daily. A practicing dentist, Bushong was an innovative “thinking man’s catcher” who put his hands first. He insisted on one day off between starts and doted on his collection of catching gloves. Most importantly, he gave the signals to Daily, a controversial idea at that time. Bushong was considered the greatest catcher in the history of the game – until Buck Ewing hit his prime. With Bushong, Daily was at his career best. On May 24 Daily beat New York and Mickey Welch 1-0 on a two-hitter. The next day he beat Monte Ward 4-3 in 14 innings, picking Ward off base twice.

He beat Chicago all three times he faced them early in the year. He shut them out 3-0 on June 23, against Larry Corcoran, and struck out 14. Chicago got the leadoff batter on base in each of the first six innings but nobody could steal. “Williamson, the most daring baserunner of them all” the Cleveland Plain Dealer wrote, “was kept rolling on the ground getting back to bases… until his uniform was covered with dirt.” Williamson made it to second base but was picked off with sand filling “half a peck into his shirt bosom.”

Accolades for this game make it the zenith of Daily’s career. “Daily pitching on Saturday,” the Plain Dealer wrote, “was the most effective ever seen here and we question whether it was ever exceeded and if indeed equaled anywhere.” The Chicago Tribune wrote: “No pitcher but Daily could have held such base-runners as are the Chicagos.” Daily beat the White Stockings again on the Fourth of July, to raise his lifetime record against them to 7-0. In his next start two days later Daily’s win streak continued and he won 3-2 over Fred Goldsmith. A controversial call by umpire Bill Burnham went a long way toward stopping a fifth inning offensive spurt by Chicago. Gore stole second base as Bushong’s throw sailed wide pulling Dunlap off the bag towards first base. Dunlap spun around however with the ball in an attempt to touch Gore on the back as he passed. It seemed an obvious missed tag, but Burnham called the out. As the fans hissed, Chicago’s big captain Adrian Anson argued the play insisting that Dunlap himself was ready to admit the missed tag. But Burnham wouldn’t hear it. He turned to the crowd and announced: “Nobody is infallible. I’m liable to mistakes. I’m human.” The governor of Illinois, John Marshall Hamilton, who was scoring the game for himself in the owner’s box, turned to Chicago president Al Spalding and badmouthed the ump.

On July 21, 1883, the Cleveland Nationals were 38-16 and, after holding first place for eight days, were one game ahead of Providence. Hosting New York with two outs in the seventh inning, and losing 0-2, McCormick suddenly walked off the mound holding his elbow. Given the strain of pitching in a pennant race, the two man staff would eventually give way to the three-man staff. But for Cleveland, first place was in Daily’s hand, and virtually Daily’s hand alone, with 44 games remaining.

In a head-to-head series, Providence took possession of first when Charley Radbourn no-hit Cleveland. Then Daily beat Radbourn and the teams traded the top spot five times in five days. With pitching arms straining, both teams went on four game losing streaks opening the door for Boston and Chicago to get back in the race. Finally, Daily walked off the field on August 1, in the sixth inning against Boston complaining of a sore arm. Pitching his third game in three days, Boston wasn’t having it. They claimed Daily was faking the injury and, under the rules, wouldn’t permit a player substitution. Both teams claimed a forfeit win but after the season the league ruled against Cleveland. For the next week the only pitcher Cleveland had was lefty Will Sawyer, a 19 year-old engineering student from Amherst College whose parents wouldn’t let him take road trips with the team. McCormick rushed himself back into action for nine starts in 19 days and then he too was completely done for the year. It was August 25. Cleveland had a two-game lead with 20 to play.

Daily came back in time to face Chicago in a huge five-game series and made his winning streak against them 10 games. He pitched the first and third games of the series winning by 5-4 and 4-3 when Bill Phillips delivered late inning run scoring hits. Before game five Chicago players spent the night in a wild celebration with Cleveland fans in a new high-rise apartment building on Stapleton Street. King Kelly tipped out a top floor window trying to smash Pfeffer’s bad-luck, yellow stove-pipe hat. His life was saved, reportedly, by Gore who grabbed him and pulled him in. Although hung over, Chicago pounded Daily 8-2 the next day to end the win streak.

Daily started six of the next nine road games while Sawyer, apparently with parental permission, and Charlie Cady were ineffective. On September 5, Daily pitched Cleveland back into a first place tie with a neat 6-1 win at Buffalo. Thanks to two rain-outs, Daily went into Philadelphia eight days later with six days of rest. Four teams, Boston, Providence, Chicago, and Cleveland, were now all within two games of each other with about 11 to play. Daily responded with a no-hitter, winning 1-0 when Bill Crowley’s seventh inning single rolled between left fielder Blondie Purcell’s legs. Daily won a four-hitter the next day and a five-hitter three days later in New York. Cleveland was now in second place, two games behind with eight to play.

But that was it. Daily’s arm was gone, and he lost his final three starts of the year with a bitter disposition. Just before Labor Day he had the fight of his career with Fred Dunlap, Jack Glasscock, and rookie Lem Hunter, on the train, with the Police Gazette running a full illustration of the brawl. When Daily complained of being pitched too much, Cleveland management threatened to withhold his salary. Many blamed Daily for losing the pennant.

On the final day of the season George Gore asked Daily to go south and pitch for a team of traveling all-stars he was organizing. Daily signed. He still had to make October exhibition starts for Cleveland and pitched well against American Association teams Louisville and St. Louis. What followed was a two-month vacation with well attended weekend games, mostly in New Orleans. Gore also signed Hick Carpenter, King Kelly, Ned Williamson, and Sam Wise. Wise would run over from the shortstop’s position and catch every return throw from the catcher for Daily.

As the lazy weeks passed, news from the North came about a rich man with a baseball hobby named Henry Lucas. Lucas wanted to resurrect the St. Louis team for the National League. Ignored by that body, Lucas founded the Union Association on December 18, 1883, as a major league and new Union franchises started signing up stars. Daily held out. Cleveland had always announced that it was against the reserve rule; a rule that allowed teams to protect up to five players for the following season. But just before the Union Association meeting, the National League announced in clear language that all players who had signed NL contracts were reserved upon the threat of blacklisting. Cleveland started threatening expulsions to its players.

In January 1884 Daily folded up his Cleveland contract and put it in his pocket. He shopped himself around for more money, earning a curt refusal from St. Louis Union manager Ted Sullivan mid-month. Then, on January 22, Larry Corcoran, who had agreed to pitch for the Chicago Union team, backed out of his deal and returned a one-thousand-dollar advance to Chicago owner Al Henderson. Daily showed Henderson (the same man who funded the Horace Phillips’ 1879 Baltimores) the Cleveland offer. Henderson beat it and Daily went to Chicago signing with the Unions, January 30. The offer was said to be just shy of $3,000 for seven months’ work. But as he signed, John Day, the New York owner Daily had also toiled for, drafted a resolution that permanently blacklisted all who went with the Union.

The Chicago Unions were the flagship team of the Union Association – until St. Louis assembled their juggernaut. A bonafide, railroad funded, Chicago semi-pro squad who played a fifty game schedule in 1883; they were so popular on a national level that Henry Lucas used their team name as the name of the new league. Unfortunately, manager Ed Hengle’s off-season strategy was inertia. Hugh Daily was the only star they signed and Hengle, whose 140 pound little brother played second base, decided to open the season with Daily as the one-man pitching staff.

Daily started the season slowly. He lost Chicago’s opener in St. Louis before six thousand fans but struck out nine in six rain shortened innings and impressed with his stump-arm’s “harness” and one-handed play. Later, he lost the home opener hosting Cincinnati, on shortstop Charlie Briggs’ ninth inning error. He was 3-6 with a 2.58 ERA and two 10-strikeout games pitching nine of the club’s first 13. Then against Washington, on May 14 and May 18, he became the first pitcher in major league history to throw back-to-back one-hitters. Washington’s captain Phil Baker spoiled the first game while pitcher Bill Wise, filling in at third base, spoiled the second. The Chicago Tribune called the May 14 effort a “perfect game.”

The one-hitters began a dominating stretch of games which raised Daily’s record to 14-8. Six of the first seven games in this run were 10-strikeout affairs. On June 1, he beat St. Louis, 5-4, when he walked and scored the winning run himself in the 10th inning. On June 9, he pitched in the first series of major league games ever played west of St. Louis, beating Kansas City, 12-3. Hengle pitched Daily more and more. On Memorial Day, Daily beat Boston 7-1 with 13 strikeouts; he also beat Boston the previous day with 12 strikeouts. In six other games he pitched with one day’s rest or on back-to-back days. His record in those starts: 4-and-2.

The heavy workload soon affected Daily’s performance. He won on June 15, giving up 12 hits, and on June 17 despite giving up 13 hits. Having reached second place for the first time all year, Chicago traveled to meet first place St. Louis, a team with a 31-4 record. On a Friday, and on two days of rest, Daily pitched a six-hitter in the opener with 13 strikeouts. He lost. He said he should have won and asked to pitch the next day. He struck out 13 again but lost to the sluggers in late innings. Despite having little left, he insisted on pitching the Sunday game as well, a third straight game in three days against the “coming” champions. He was pounded. The following series in Baltimore should have been a triumphant homecoming. Proud Baltimoreans came out for Daily only to see the pitcher hammered for 31 runs in three starts. Hengle moved Daily to the outfield in the seventh inning of the Baltimore opener snapping Daily’s streak of 33 consecutive complete games. Daily had another incomplete game against last-place Philadelphia on the Fourth of July, his losing streak seven long, he walked off the field in the fifth inning cursing at the umpire. Chicago’s losing streak was now 11 long. The team slid from second place to fifth place, well below .500, in 18 days. But there would be no rest for Daily. Chicago traveled to Boston and Daily pitched in his regular turn.

On two days’ rest, on the current site of what is now a Turner Fisheries restaurant east of Fenway Park, Hugh Daily spun his third one-hitter of the season: a one-hit, 20-strikeout, no-walk performance for a Bill James game score of 105, the highest ever attained by a major-league pitcher. Daily’s delivery was flirting with an illegal height, and ump Pat Dutton’s repeated warnings of “Watch it, please” echoed in the early part of the game. Daily struck out seven in a row, many on beautiful curves. Finally, with two outs in the fourth inning, Boston had their first baserunner when shortstop Walt Hackett was awarded his base on a pitch released by Daily way over the hip. Boston’s big slugging catcher Ed Crane got the only hit of the game – a triple to left-center – with two outs in the sixth inning. Two other batters reached First on errors.

Unfortunately, the game was logged as a 19-strikeout performance: game score 10-4. With two outs in the bottom of the fifth inning, Krieg dropped a third strike and threw wild to first base allowing Pat Scanlon to reach. The rule book was clear for dropped third strikes whether or not the batter reached base – Daily would get his 20th strikeout. But the rule book was not clear on errors on dropped third strikes. Daily was not awarded an assist or a strikeout and Scanlon reached first on an error. The Boston Morning Journal, among other newspapers, reported the game as a 20-strikeout performance, unofficially breaking the 19-strikeout record set by Charlie Sweeney exactly one month earlier. Daily threw another one-hitter three days later giving him back to back one-hitters twice in the same season.

For the month of July 1884, Hugh Daily logged 94 innings, allowed 50 hits, struck out 108 and walked seven, with a minuscule 1.04 ERA. His record was 5-5. Good news came on July 23 when Chicago induced promising rookie Al Atkinson to jump from the Philadelphia Association club to alternate with Daily as part of a two-man staff. Chicago also signed Gid Gardner of the Baltimore Association. These signings could explain the team’s eviction from the Union Grounds on August 1st for non-payment of rent. A weekend against Cincinnati became two exhibition contests at an unspecified field. Daily’s 1-0 win on that Saturday is often incorrectly counted as his fifth shutout of the year. With the schedule showing Chicago on the road until August 25, Henderson pulled a neat trick. He leased a field in Pittsburgh, rechristened the Chicago club as “Pittsburgh,” and, keeping their maroon uniforms and old gold caps, hosted St. Louis there for five games before hitting the road again.

Daily went 4-6 in August primarily because he pitched most of the games against St. Louis, a team that seemed to be improving after their 31-4 start with an eight week stretch of .947 ball. Daily handed St. Louis one of their two losses in that period, an 11-inning 3-2 squeaker before three thousand fans in the Pittsburgh opener. This raised his record for the year to 23-23. In his other five August starts against St. Louis, he was winless. He lost in 11 innings August 17, when veteran Harry Wheeler dropped a fly ball, and he lost in 11 innings two weeks later when Orator Shaffer led of the bottom of that inning with a home run. A fourth extra-inning complete game for the month came August 19, at Cincinnati, when he bested his old Cleveland teammate Jim McCormick. Harry Wheeler made amends for his muff by helping Daily with a game-winning triple.

In all, Daily made 10 starts for “Pittsburgh” as the team played in the east. He won five and lost four, with a complete game tie in Washington, finishing with a neat shutout at Baltimore. Tony Suck had to catch him as Krieg had his hand split by Daily’s speed. But Daily busted up Suck’s hand in the seventh inning of his shutout. The game might have become a forfeit loss until Kid Baldwin, an idle Kansas City player watching the game, offered to jump in to catch the final eight outs. Pittsburgh had only to play Wilmington before heading back west to their tentative home field. But Wilmington disbanded, September 15. The Henderson brothers, owners of both Pittsburgh and Baltimore, had their two teams play an exhibition game, on September 19, for the purposes of picking the best talent for one club. The next day, Pittsburgh was disbanded, and Daily was one of 10 players released. Despite inferior stats, Atkinson was picked to alternate for Baltimore with Bill Sweeney.

Hot-headed Mike Scanlon, a long-time investor in Washington baseball clubs who figured he knew enough to manage, gave Daily two starts to impress and make the Washington squad for their final Western swing. Daily did beat Boston, September 25, relying on curves, but was blown out by Cincinnati 15-0 and Washington dropped him. Because of darkness, Cincinnati’s six-run eighth inning was taken away and the final score is logged today as 9-0. Daily’s monster season was over. He reached 483 strikeouts despite being released with nearly one month to play. He didn’t know it, but at the age of 37, he would win just seven more major league games.

No team knew that, either. As 1885 unfolded, contract offers for Daily poured in -even though he was on the official blacklist per the Day resolution. In mid April Daily was accepted back into organized ball per his payment of $500. He held out for a month and then signed the best offer he could; with the ex-Union now National League St. Louis team the evening of June 2. St. Louis was desperate after opening with an 8-14 record, a far cry from their 1884 dominance. Henry Boyle’s arm was useless and Lucas had given a four start trial to a pitcher he scouted himself in

Prospect Park: Billy Palmer.

Daily joined just in time for the biggest series: in Chicago. The White Stockings unveiled a brand new ballpark, West Side Park, June 6, the current site of the Jackson Academy School. In front of over 10,000 fans, the largest crowd of his career, he walked eight, struck out none, and was losing 9-0 by the sixth inning. Chicago ace John Clarkson took himself out at that point and second baseman Fred Pfeffer pitched the final three innings. The final score was 9-2 with old pal George Gore going 4-for-4 with two home runs. Despite the fact that Daily’s effort could be attributed to a want of practice, he did not take the loss well. “The usual exhibition of temper,” the St. Louis Post Dispatch reported. Daily’s next start came in the final game of that series and was even worse. He walked five and struck out none absorbing a 1-13 loss. The Chicago Tribune reported that Daily was “utterly bewildered at the manner in which he was pounded.”

But the magic wasn’t gone yet. Nine days later Daily made his home debut and started against Detroit. He won a 3-0 one-hitter, scored two of the three runs, and helped the other run score when he faked a steal of second base. He lost to Boston pitching a five-hitter in his next start due to a little umpire controversy. In the second inning, Boston’s Jim Manning, the runner on third, bumped third baseman Ed Caskin trying to catch Daisy Davis’ popup. Ump Stew Decker stunned everybody ruling a “do over,” and Davis batted again, extending a game tilting three run rally. Harshly criticized, Decker resigned as an umpire after the game.

Daily beat Philadelphia twice in the week before the Fourth of July, the second game a gift when first baseman Sid Farrar made a wild throw in late innings. Then the one-armed hurler lost to Providence in the bottom of the ninth when third base coach Jerry Denny ran down the line to home plate, blocking Fatty Briody from tagging the real runner, Arthur Irwin. Ump Charlie Cushman allowed the block claiming, to the disgust of many, that Denny never touched Briody. Daily didn’t come close to winning again. Reports started circulating that the St. Louis players were trying to lose when Daily pitched. That’s when on July 23, at the Polo Grounds, five players made 10 errors behind him for 11 unearned runs. St. Louis lost 15-3, and Lucas released Daily right away.

As Daily’s skill decreased with age, teams tolerated less and less of his divisive vulgarity. In 1886 Mike Scanlon, the manager who cut Daily near the end of 1884, signed him to alternate with Dupee Shaw when pitcher Bob Barr was holding out. Daily’s catcher was Ed Crane, the Boston Union slugger who tripled in his 20-strikeout game. In six complete game starts Daily was wild, vocal, hit hard, and ineffective. Allegations that Daily was a drinker surfaced, and he lost every game he appeared in. Washington absorbed an early season 12-game losing streak and quickly gave in to Barr’s demands, making Daily expendable. In his first loss, hosting Boston before the Washington crowd, he was tagged for four runs in the first inning. King Kelly threw Daily’s little bat to Tim Murnane in the press box as a “pencil.” His last five losses came on the road. Tim Keefe beat him with a four-hit shutout in New York, and Henry Boyle beat him with a four-hitter in St. Louis. Boyle himself got five hits and two home runs off Daily. Cap Anson, of all people, stole a base in the four-run first inning of the Chicago home opener, May 18. Then Daily’s last two starts came on one day of rest each. He lost an 8-10 game in the ninth inning to Chicago, and got blown out in his last game by Detroit during their 19-3 start. Detroit led 9-1 in the fourth inning and the large Saturday crowd contented themselves the last five innings watching a drunk down the left field line pick fights.

In his fall from the ladder of fame Daily hit every rung. He returned to Baltimore, where he pitched for small teams for small dollars before signing with New Castle, Pennsylvania, a club that needed a pitcher for an Ohio road trip. Then his first big offer came from Ted Sullivan, manager of the Milwaukee, Northwest League team. He signed on July 19, and Sullivan immediately advertised Daily as Milwaukee’s new ace. But Daily dilly-dallied and pitched one last game for New Castle in Wooster, Ohio, 10 days later against amateurs while Sullivan threatened expulsion. Daily lost.

Daily finally reached Milwaukee on July 24, and bested first place Duluth’s young ace, Mark Baldwin, with a three-hitter. Daily made 15 starts in far-off Minnesota and Wisconsin, going 9-6 with a 1.10 ERA. He claimed soreness on a few occasions, once forcing manager Sullivan to pitch a game, August 6, against Eau Claire. Daily beat Baldwin again, September 8, as Milwaukee struggled to get to .500, and then jumped to John Barnes’ St. Paul team. Sullivan wouldn’t expel Daily, saying “Daily’s loss is a gain. He was continually making discord.” Daily did sad work in St. Paul, winning only once, with an ERA of 2.63. After six starts the minor league players refused to take the field behind Daily and he was released. In one loss at Eau Claire, Wisconsin, September 19, fans chanted “Cripple, cripple, cripple!”

Claiming he was “Anxious to redeem himself” and having “entirely discarded the use of stimulants,” Daily begged for a tryout with Billy Barnie’s 1887 Baltimore team. Barnie was well stocked on pitchers, but recommended Daily to Jimmy Williams, manager of the new Cleveland American Association team, while that team was losing in the East. Daily signed on June 13, and lost big in Philly in his debut two days later, giving up 18 runs. He won three out of his next four but lost eight in a row – the last three despite leading in late innings. He was tired, slow, lacked command of the ball, and couldn’t watch the bases. On August 13 he lost his ninth in a row when Cincinnati’s sub Heinie Kappel hit a two-run double in the top of the ninth inning. Kappel had been hit by a pitch to load up the bases, but ump Wes Curry wouldn’t allow it, claiming Kappel intentionally leaned into the pitch.

Daily’s last major league start came on August 21, 1887, in the first Sunday game in Cleveland history. Although team owner Frank Robison pushed a law allowing Sunday baseball through the city council three weeks earlier, puritan civic organizations effectively blocked the game at League Park citing state statutes. At the last minute, Robison selected a well-known site five miles east: the Cedar Avenue Driving Park, currently the football field of Cleveland Heights High School. Daily battled against speedy left-hander Ed Cushman in a rain-shortened eight-inning game, losing 5-7. Daily gave up five unearned runs in the second inning after a 30-minute rain delay.

Daily caught a stiffness pitching in the rain and begged off his next start, August 26. He was day-to-day with “rheumatism” and sent home to Baltimore to recover. When Cleveland arrived in Baltimore on September 1, Daily was given two more chances to pitch but said he couldn’t. Williams released Daily on September 3.

Daily spent the next six years jumping between semi-pro teams and earning about fifty dollars a month. He worked as a nail maker and umpired some games in Western Indiana in 1899. September 7 of that year Daily called a forfeit loss against Danville in a game at Terre Haute when Danville catcher Fred Abbot turned around and punched him. Daily flipped his stop watch to a bystander and popped Abbott with his good hand.

He seems to have lived in Philadelphia and Baltimore after that. In Baltimore, Daily lived with his two unmarried sisters, Hugh working odd jobs and Bridget the head of the household. He’s listed as a night watchman on Maryland census records and last appears in the Baltimore phone book in 1922. The circumstances of the death of Hugh Daily, the one-armed pitcher, remain as mysterious as his origins.

Sources

Baltimore Sun, 1884: 6/24.

Boston Globe, 1882: 7/25, 8/18; 1887: 4/10; 1906: 11/25.

Boston Morning Journal, 1884: 7/8, 10/8; 1886: 5/3, 5/21.

Brooklyn Daily Times, 1880: 8/24.

Brooklyn Eagle, 1887: 8/3.

Buffalo Courier, 1881: 9/23; 1882: 3/6, 3/31, 4/2, 4/16, 4/19, 4/23, 4/29, 5/2, 5/21, 5/24, 5/30, 6/6, 6/13, 7/2, 7/14, 7/16, 7/25, 7/27, 8/2, 8/5, 8/31, 9/1, 10/1.

California Spirit of the Times and Underwriters Journal, 1887: 9/17.

Chicago Inter-Ocean, 1884: 6/20, 7/5.

Chicago Tribune, 1881: 8/14; 1882: 5/16, 5/17; 1899: 9/7; 1906: 4/8.

Cincinnati Enquirer, 1884: 4/26, 4/28, 5/15, 5/19, 6/5, 6/11, 6/26.

Cleveland Plain Dealer, 1882: 5/25; 1883: 4/4, 4/10, 4/27, 5/13, 5/18, 5/24, 5/25, 6/22, 6/24, 7/11, 7/14, 7/21, 7/26, 8/2, 8/20, 8/22, 8/27, 8/28, 9/1, 9/4, 10/23; 1887: 6/12, 6/15, 6/16, 6/17, 6/27, 7/10, 7/15, 8/7, 8/14, 8/19, 8/21.

Kansas City Evening Star, 1884: 6/16.

Los Angeles Times, 1892: 7/18.

Milwaukee Daily Journal, 1886: 7/20, 7/23, 7/25, 7/30, 8/7, 8/9, 9/6; 1892: 7/13.

National Police Gazette, 1906: 5/19.

New Orleans Times Picayune, 1882: 11/9, 11/14, 12/26; 1883: 9/26, 10/1, 10/22, 10/29, 10/31, 11/3.

New York Clipper, 1876: 5/13, 9/18, 9/30, 11/4; 1877: 4/20, 7/29, 8/25, 9/1, 9/8, 10/6, 10/13, 10/20; 1879: 8/30; 1880: 4/17, 4/24, 5/1, 5/22, 7/3, 7/24, 8/28, 9/12, 10/3, 10/10; 1881: 5/12, 8/20, 8/27; 1882: 5/20, 8/5, 8/12, 8/19; 1884: 8/30, 9/27; 1885: 4/25; 1887: 7/13, 9/17.

New York Daily Tribune, 1880: 10/3.

New York Herald, 1880: 10/12; 1881: 4/5, 5/5, 5/16, 8/5, 8/18.

New York Sun, 1881: 6/18, 9/22, 10/2.

New York Times, 1880: 8/13, 8/15, 8/17, 8/18, 8/22, 9/3, 9/16; 1883: 6/15; 1885: 4/19; 1887: 8/22.

Providence Daily Journal, 1877: 6/4.

Rochester Morning Herald, 1880: 6/19.

St. Louis Post Dispatch, 1883: 10/26, 10/30, 11/17, 12/27; 1884: 1/23, 1/29, 1/31, 4/22; 1885: 6/6, 6/8, 7/17, 7/31.

St. Paul-Minneapolis Pioneer Press, 1886: 9/5, 9/14, 9/20, 9/23, 9/28.

St. Paul Post Dispatch, 1886: 9/5.

Full Name

Hugh Ignatius Daily

Born

July 17, 1847 at , (Ireland)

Died

, -- at , ()

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.