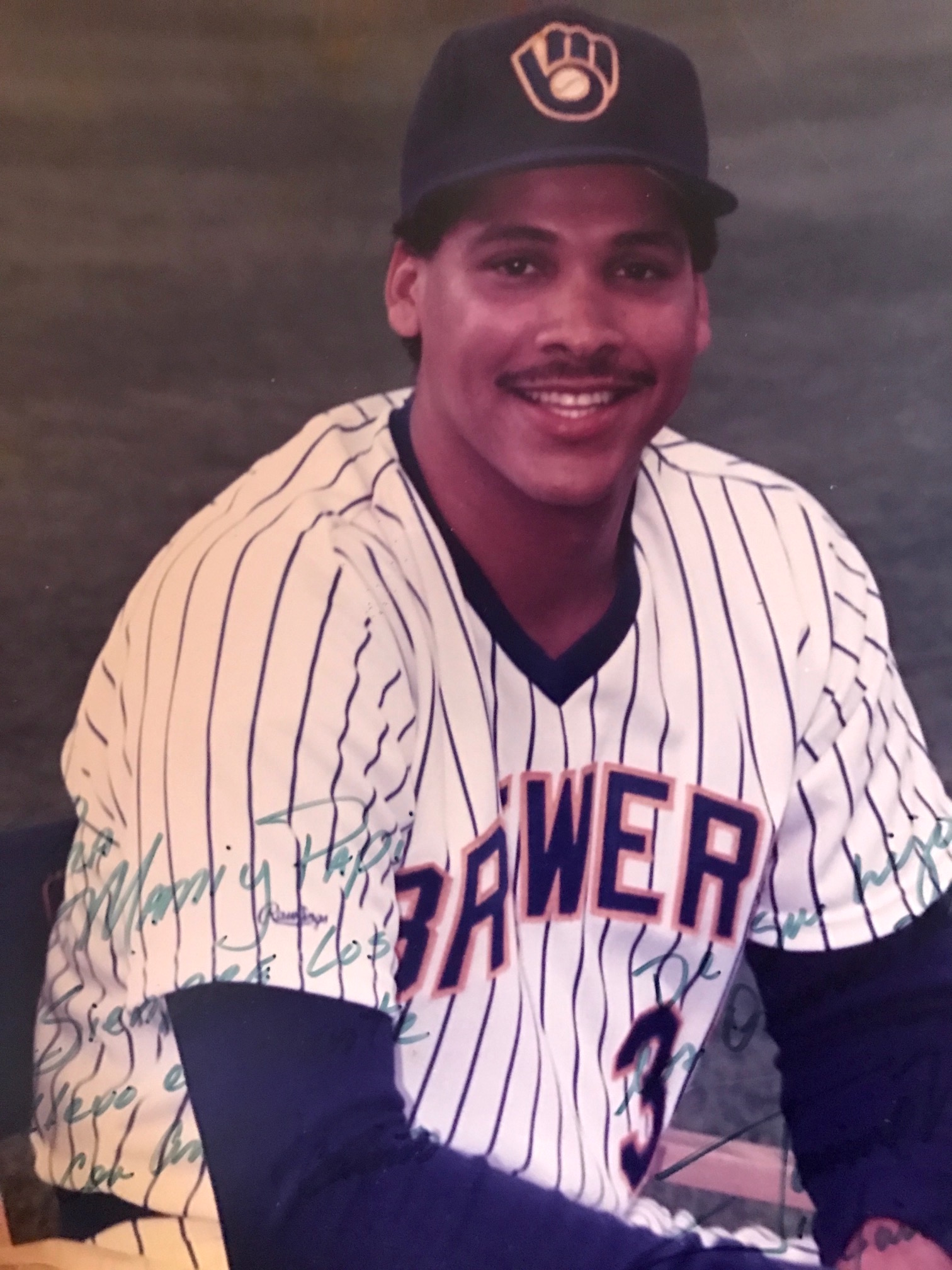

Jaime Navarro

Puerto Rico and baseball. From the legendary Roberto Clemente and Orlando Cepeda to Roberto Alomar, Carlos Beltran, Carlos Delgado, and Pudge Rodriguez, the small island with only 3.5 million inhabitants has left an indelible footprint on the major-league landscape. As of 2016, the Caribbean nation has produced no fewer than 250 big-league players, including at least 65 pitchers. Among those hurlers is right-hander Jaime Navarro, a durable workhorse during his 12-year career (1989-2000) spent primarily with the Milwaukee Brewers, Chicago Cubs, and Chicago White Sox. Upon his retirement, he joined southpaw Juan Pizarro (1957-1974) as the only Puerto Ricans with at least 100 wins and 2,000 innings pitched, forming a select fraternity that has welcomed only one additional member, Javier Vazquez (1998-2011).

Jaime Navarro had baseball in his blood. He was born on March 27, 1967, in Bayamon, in Puerto Rico’s northern coastal valley, to Julio Navarro and Ana Cintron de Navarro. “Whiplash,” as Jaime’s father was known, was a right-handed side-arm pitcher who played six seasons (1962-1966, 1970) in the big leagues in a professional career that spanned four decades. According to Ana Navarro, Julio was strict with their son and instilled in him an intense work ethic.1 The young Jaime experienced firsthand the sacrifices his father made as a professional ballplayer that required him to spend a great amount of time away from the family. “It’s a hard life,” the elder Navarro would say. Jaime seemingly grew up at baseball parks. His mother recalled an episode when he sold candy at a game in Mexico, where his father had played, but ended up giving the candy to all of his friends and owed the vendor money. On another occasion, Jaime was dressed nicely at a game when his father’s teammates encouraged him to run the bases, yelling, “Here comes Jaimito! Slide, Jaimito, slide,” which he, of course, did.

Jaime was always on the move as a kid, perhaps even hyper. He eventually channeled that energy into baseball. Always big for his age, Jaime played any position he could — catcher, first base, and outfield — before finally moving to the mound where he could display his strong right arm. “I learned a lot from being around people like (Henry) Aaron, (Willie) Mays, and (Orlando) Cepeda,” said Navarro. “But especially Jose Morales.”2 Jose was Jaime’s godfather. Julio Navarro and Morales were both born on St. Croix in the US Virgin Islands, where they also learned to play baseball. They were close friends and, according to Jaime’s mother, Ana, enjoyed speaking the local patois together.

After a stellar baseball career at Luis Pales Matos High School in Bayamon, Navarro accepted a scholarship to attend Miami-Dade Community College (Wolfson, downtown campus). He played for coach Steve Hertz, who had an accomplished record of churning out prospects, many of whom enjoyed success in the big leagues, like Mickey Rivers, Warren Cromartie, and Bucky Dent. Soon after donning the Sharks uniform for the fall season in 1986, Navarro drew interest from scouts. Over the next two years, Steve Souchock and Bo Osborne of the Major League Scouting Bureau charted Navarro’s development in reports made available to all big-league clubs. They described him as having a good, loose arm and average to above-average velocity on his fastball with the potential to develop into a sinker-slider type hurler.3 Navarro was selected twice by the Baltimore Orioles, in the second round of both the 1986 January and June (secondary phase) drafts, but chose not to sign because the Orioles did not offer the kind of bonus the Navarro family felt was warranted.4 On the recommendation of team scout Julio Blanco-Herrera, the Milwaukee Brewers chose Navarro in the third round of the 1987 amateur draft. No longer eligible to play JC baseball, Navarro signed. According to Ana Navarro, Felix “Felle” Delgado, a longtime player from Puerto Rico and then a Brewers scout, helped in the signing process. “Give him the money,” she recalls Delgado saying. “He’s good. He’s worth it.”5

Navarro blew through Milwaukee’s farm system with the force of a hurricane hitting his homeland. He struck out 95 batters in 85⅔ innings with the Helena (Montana) Brewers in the Pioneer League (Rookie) in 1987. The following season he went 15-5 with the Single-A Stockton Ports, runners-up for the California League championship. Despite having only 39 professional starts under his belt, Navarro participated in the Brewers spring training in Chandler, Arizona, in 1989, as a nonroster invitee. Ranked as the club’s second-best prospect (after slugger Gary Sheffield), Navarro needed to keep his suitcase packed. He went from the Cactus League to the Texas League, where he overpowered Double-A opposition in 11 starts (5-2, 2.47 ERA, 78 strikeouts in 76⅔ innings) as a member of the El Paso Diablos, and then had a brief, three-start pit stop with the Denver Zephyrs of the Triple-A American Association.

About two years after starting his professional career, Navarro was called up by the Brewers on June 19 to stabilize an injury-riddled staff, which had finished second in the AL in team ERA a year before. Starters Juan Nieves and Bill Wegman were on the DL; two other starters, Chris Bosio and Bryan Clutterbuck, were playing with injuries. On June 20, 1989, Navarro debuted, tossing 6⅔ innings, yielding two runs (one earned) in a no-decision against Kansas City. “I thought the kid threw great,” said pitching coach Chuck Hartenstein. “He threw a couple of pitches 94 [mph]. I saw some bats that were slow getting to it.”6 He was noted for his heater, but Navarro’s arsenal also included a slider, a slight change, and a forkball. A hard thrower, he primarily pitched to contact throughout his career, and relied on location and movement for success. Five days after his debut, Navarro notched his first victory by scattering nine hits over 7⅓ innings and striking out a season-high seven batters against the Chicago White Sox. “Talent-wise,” said All-Star closer Dan Plesac, “he’s the best I’ve seen come up.”7 Earning a permanent spot in the rotation with his consistency, Navarro concluded the campaign with an impressive 3.12 ERA (ranking second behind Bosio’s 2.95) in 109⅔ innings for the fourth-place club. Navarro (7-8) drew praise from team brass for his maturity, composure on the mound, and his inquisitive attitude. “He’s a very polished young man,” gushed Hartenstein, who like skipper Tom Trebelhorn was unsurprised by the 22-year-old’s success. “He handles himself very well from the mental part of the game.”8

While the Brewers got off to an unexpected hot start in 1990, occupying first place in the AL East as late as June 3, Navarro stumbled out of the gate. After 10 mostly ineffective outings, none of which went longer than six innings, his ERA was 6.65, resulting in a demotion to Denver. “His stuff is still good,” said veteran backstop Charlie O’Brien about Navarro’s sophomore slump. “He’s just missing the spot. He’s throwing too many pitches to hit.”9 Navarro ironed out some kinks in six starts with Zephyrs and was recalled earlier than expected to shore up a staff once again decimated by injuries. After posting a stellar 1.59 ERA in 22⅔ innings in nine relief appearances in July, Navarro rejoined the starting rotation. “[Pitching coach Larry Haney] told me to work like I was in the bullpen,” he said. “Just come after everybody, and think about getting people 1-2-3, one inning at a time.”10 After a few rough outings, Navarro tossed consecutive complete-game victories to beat New York and Toronto on the road at the end of August. He concluded the season on a high note by going the distance to beat the Yankees, picking up his fifth victory in his final seven decisions.

Navarro arrived at the Brewers spring training in 1991 buoyed by his success in the Puerto Rican Winter League. For the fourth consecutive season, he pitched for Santurce, a club located in the capital city of San Juan. He logged in excess of 100 innings for the Crabbers, leading the tradition-rich club to its first title in 18 years. The Brewers, who faded after their hot start the year before and finished in sixth place, counted on Navarro to emerge as a bona-fide starter, yet took a cautious approach. “We might have expected too much from him. It was a combination of many things,” said Haney of Navarro’s struggles. “But more than anything, it was a young pitcher, who wasn’t controlling his emotions. He was trying to be better than he was.”11 Navarro once again had a rocky April (6.27 ERA after four starts), then was whacked in the thigh by a screaming liner off the bat of Minnesota’s Kent Hrbek in his next start, and suffered a deep bruise. Navarro’s desire to pitch through pain impressed his coaches and teammates. “He wants the ball,” said Haney. “A lot of pitchers would have missed some starts with that injury.”12 On May 24 Navarro needed just 96 pitches to toss the first of eight career shutouts, a masterful four-hitter with no walks to beat Cleveland 1-0. Five starts later he twirled another four-hitter, defeating Seattle, 4-0, also at County Stadium. “This is my year,” said Navarro jubilantly after the game. “I’ve been working hard and my arm is still strong.”13 No one doubted Navarro, who emerged as the unequivocal ace of the staff. He surged beginning July 28, going 8-4 with five complete games in his last 14 starts, and holding opponents to an impressive .239 batting average. In addition to his 15-12 slate and 3.92 ERA, Navarro ranked ninth in the AL in innings pitched (234), seventh in starts (34), and third in complete games with a career-best 10.

Navarro proved that he was no one-year-wonder by winning a career-high 17 games in 1992. For the second straight campaign he was locked in after the All-Star break, posting a 1.25 ERA and limiting opposition to a paltry .182 batting average in his first eight starts during the most impressive stretch of his career. It started with what sportswriter Tom Haudricourt of the Milwaukee Sentinel called a “string of dominating performances.”14 After limiting the White Sox to just one hit over eight innings in the Brewers’ eventual 4-3 win in 11 innings on July 17, Navarro hurled his first and only two-hitter five days later to beat Texas 4-1 at County Stadium; the only Rangers run was unearned. Then came the best game of his career: a three-hit shutout, requiring just 85 pitches, with no walks against Cleveland. “You can’t throw the ball any better,” said teammate Kevin Seitzer.15 “When he’s on,” said Cleveland’s Paul Sorrento, “he’s one of the best in the league.”16 Navarro’s success was not lost on skipper Phil Garner, whose club surged in September (winning 22 of 28 games at one point) to engage Toronto in a fierce battle for the division crown. “He just overpowering people,” said the feisty pilot, in his first of eight years guiding the team, after Navarro shut out Baltimore on five hits on September 12. Navarro (17-11, 3.33 ERA), Wegman (13-14, 3.20), and Bosio (16-6) were the first trio of Brewers pitchers since 1979 to log at least 200 innings each, and anchored a staff that led the AL in team ERA (3.43) for the first time in franchise history.

Navarro’s emergence as one of the most durable starters in the AL was followed by a startling, rapid decline, eventually resulting in his banishment to the bullpen and departure from the club. Always a husky player, the 6-foot-4 Navarro arrived at Brewers spring training in 1993 weighing upward of 250 pounds, well over his listed playing weight of 215. Out of shape, he developed back pain and struggled in 1993 as the Brewers dropped from 92 wins to 69 and landed in the cellar. “[Navarro] wandered aimlessly for much of the season” opined beat writer Tom Haudricourt, reflecting on the pitcher’s 11-12 record and abysmal 5.33 ERA (second highest in the AL) in 214⅓ innings.17 Navarro started 34 games for the third consecutive season, but was liable to unravel early in the game; seven starts lasted less than five innings.

As bad as 1993 was, the next year was worse. “[Navarro’s] a key guy,” said pitching coach Don Rowe, expecting a bounce-back campaign from the big right-hander. “We need a good year out of Jaime.”18 But when the hurler once again arrived in camp overweight, and developed a sore arm, Garner was livid, demoting him to fifth starter. “We can’t afford to have the entire rotation messed up because Jaime’s not ready,” said Garner, once known as Scrap Iron as a player. “It’s not fair to the other pitchers.”19 Navarro made just eight starts (with a 7.74 ERA) before Garner banished him to the bullpen for the remainder of the season. “Jaime’s been blessed with a great arm,” said the skipper, “and has shown he can bounce back.”20 Going from staff ace to mop-up artist was hard on the 27-year-old, who feuded with Garner and reporters. After the players’ strike interrupted the season on August 12, and ultimately forced the cancellation of the rest of the season and the playoffs, no one expected Navarro to be back with the club whenever, and if ever, a new season began. At 4-9 with a hard-to-fathom 6.62 ERA in 89⅔ innings, Navarro’s transformation from an integral component of the Brewers’ future to outcast was complete.

Eligible for salary arbitration, Navarro was not tendered a contract offer by Milwaukee, and was declared a free agent on April 7, 1995. Two days later he signed a three-year pact with the Chicago Cubs with the option of terminating the deal after two years. “We’re hoping to catch lightning in a bottle,” said Cubs GM Ed Lynch.21 The North Siders didn’t have much to lose. They were coming off a last-place finish in the NL East in 1994; only one starter had won more than 10 games in any season in his career, and that was 35-year-old Mike Morgan, who was coming off a horrendous campaign (2-10, 6.69 ERA). A slimmed-down Navarro made a good initial impression on skipper Jim Riggleman when he arrived at the Cubs’ camp in Mesa, Arizona, weighing 225. “Maybe it was the weight,” responded Navarro when queried about his two-year struggle on the mound. “I guess because I wasn’t pitching well they’ve got to blame it on something.”22 Navarro made a big splash in his Cubs debut, on April 29 at Wrigley Field by scattering five hits and two runs (one earned) over seven innings against Montreal to notch his first win in the NL. The only Cubs starter with a winning lifetime record, Navarro won his first four starts and first five decisions, making Lynch look like a genius. “He’s the kind of guy, from what he’s done in the past, who can step forward and show the way,” boasted Lynch.23 Navarro quickly emerged as the ace on a young, unproven staff. “The key to me is being consistent,” he said after holding Philadelphia to two hits in 8⅓ innings in a victory on July 8. “I just wanted to put it in there where they could hit it and get some outs.”24 Those words reflected the rejuvenated pitcher’s approach all season long. He tossed at least six innings in 25 of his 29 starts; only once did he fail to go at least five. In helping the Cubs to just their fourth winning season (73-71) in 23 years, Navarro ranked fifth in the NL in wins (14) and innings (200⅓) while posting a career-low 3.28 ERA.

The Cubs were fully aware that Navarro wore his emotions on his sleeve when they signed him. Like many pitchers, he had a tendency to sulk when pulled from a game, and overstepped boundaries when he occasionally criticized players for errors. But no one was prepared for what one commentator called a “shameful incident” involving Navarro on May 14, 1996, at Houston’s Astrodome.25 Tension in the clubhouse was already high when neither the Cubs nor Navarro replicated their hot start from the previous season. Navarro won just two of his first eight starts and seemed to be pressing. “He was slow and methodical last year,” said pitching coach Fergie Jenkins. “This year he’s more herky-jerky.”26 When Riggleman yanked Navarro in the seventh inning against Houston, after he surrendered 10 hits and six runs, the pitcher went ballistic, confronting his skipper and catcher Scott Servais on the mound. The heated, profanity-laden tirade continued in the dugout. Though Navarro issued a scripted public apology, the damage had been done. “When a pitcher of Navarro’s caliber is allowed to leave the way the Brewers let him go,” said Riggleman in an excoriating tone to the press, “there must be reasons, and some of them are becoming apparent.”27 The episode had a profound impact on the way members of the Chicago media perceived Navarro for remainder of his career in Chicago (including three years with the White Sox). Longtime Tribune writer Bob Verdi was unapologetic in his response to Navarro’s outburst. “[M]anagement should send a message and cut its losses before it’s too late,” he suggested. “[His] tantrums violate everything this rebuilding plan is supposed to represent.”28 Surprisingly, Navarro wasn’t suspended, and turned into what the Tribune’s Mike Kiley called a “dynamic presence” for the underachieving fourth-place Cubs (76-86) by fashioning an eight-game winning streak from July 26 to September 8.29 While Riggleman offered a backhanded compliment (“Jaime’s never really composed on the mound. There are a lot of competitors who need to have a little nastiness in them”), sportswriters (and probably teammates) wondered when the increasingly erratic Navarro’s next meltdown would be.30 Despite the self-created distractions, Navarro was a dependable workhorse, posting another stellar season (15-12, 3.92 ERA in 236⅔ innings, fourth most in the NL) which made his antics easier to tolerate for management. Even Servais, with whom he feuded all season, recognized the hurler’s “stuff.” “With Jaime, you go with his strengths and don’t worry about the batter,” he said. “There’s not many guys in the league you can do that with.”31

In the offseason, Navarro exercised his free-agent option and on December 11 signed a reported four-year, $20 million contact with the Chicago White Sox, considerably better than the Cubs three-year, $14 million offer.32 “[Navarro] led the team in hissy fits, dugout confrontations and stubbornness,” opined Tribune sportswriter Gene Wojciechowski. “[He] is just enough pain that nobody felt bad when he switched leagues.”33 Unfortunately for Navarro, the wrath of the Chicago sports reporters followed him to the South Side of town.

In retrospect, Navarro’s tenure with the White Sox was an unmitigated disaster. He posted a cumulative 25-43 record with an atrocious 6.06 ERA in 542 innings in three seasons in what is often considered among the worst free-agent signings in major-league history. Navarro is also cited as one of the reasons the White Sox implemented an informal policy of not offering free-agent pitchers contracts for more than three years (still practiced as of 2016). Navarro verbally sparred with teammates, ownership and management, and sportswriters, who, in turn vilified him in the papers. Though the pitcher might have deserved bad press, some comments about his weight or commitment to baseball bordered on racism.

Coming off a second-place finish in the AL Central in 1996, the White Sox were widely considered the favorite to win the division crown in 1997 with two-time MVP Frank Thomas, Robin Ventura, and free-agent signing Albert Belle in the lineup. But the clubhouse soon evolved into what beat writer Bernie Lincicome described as “an unhappy place … a jealous and jumpy place,” filled with envy, resentment, and indifference.34 When Ventura went down with a broken ankle in spring training and missed the first 99 games, a void in leadership was readily apparent. With the club struggling to play .500 ball, yet just a few games off the division lead, management dumped salaries in high-profile deals that exacerbated tensions. “[W]e weren’t too happy,” said Navarro after starting pitchers Wilson Alvarez and Danny Darwin and closer Roberto Hernandez were sent to San Francisco for six prospects on July 31. “But we just have to go out and play the game. This is our game, not the owner’s game. We represent ourselves. Maybe the owner has given up, but we didn’t.”35 Regrettably for Navarro, his lucrative free-agent deal which bestowed upon him the status of staff ace and the perquisite of the Opening Day starter, and his season-long funk fanned the flames of discontent on the team. On the day the White Sox announced the blockbuster trade of his mound mates to the Giants, Navarro failed to protect a nine-run lead, surrendering 11 hits and 11 runs in 4⅔ innings to the Anaheim Angels in an eventual 14-12 Chicago victory. The White Sox finished in second place with a losing record (80-81) while Navarro’s roller-coaster career took yet another dip. In addition to his 9-14 slate and staff-leading 209⅔ innings, he posted the highest ERA (5.79) and surrendered the most hits per nine innings (11.5) in the majors. Viewed from another angle, his season was not much worse than those of two teammates, James Baldwin (12-15, 5.27) and Doug Drabek (12-11, 5.74). Chicago left Navarro unprotected in the expansion draft, but predictably neither the Arizona Diamondbacks nor the Tampa Bay Devils Rays took the bait.

The situation worsened for Navarro in 1998 as his performance on the field sank to a new low. He tied for the AL lead with 16 losses, won just eight times, and once again led the majors in highest ERA (6.36) and most hits per nine innings (11.6) while the White Sox once again finished in second place despite a losing record in the weak AL Central Division. It was a vicious cycle, indeed nightmare, for Navarro, who must have had skin as thick as a rhinoceros. While sportswriters mercilessly lampooned Navarro in the press for his poor performance and weight (which had ballooned to 250 or more), Navarro added fuel to the intoxicating fire with clubhouse blowups and incendiary remarks. “We’re not a team right now,” said Navarro after a shutout loss to Detroit on May 30. “We stink. Nobody’s pumped up. It’s like a cemetery … a bunch of dead dogs. Our guys are worried about their own stats, not the team.”36 No one could doubt Navarro’s competitive spirit, but his public comments didn’t endear him to fans or teammates. After Boston pounded him for nine hits and eight runs (six earned) in a loss on July 5, Navarro had another meltdown. “To be honest with you, I don’t want to be here. Maybe I should ask for a trade. I’m not helping the team. It’s embarrassing.”37 But Navarro’s contract was an albatross around GM Ron Schueler’s neck.

In stark contrast to Navarro’s generally negative portrayal in the press was the pitcher’s mainly unreported but no less positive contributions to his community. For example, he donated at least $20,000 in 1994 to the baseball program at his alma mater in Miami.38 He was involved in a number of charitable organizations in Milwaukee and Chicago, was a regular speaker at events focusing on the Latino community, and sponsored scholarships for Latino students to attend community college.39 Navarro never forgot his Puerto Rican heritage. He echoed comments, widely perceived as inflammatory at the time, by stars Roberto Alomar Jr. and Rafael Palmeiro that baseball management did not bestow the same recognition and respect upon Latino ballplayers as it did whites or African-Americans, and suggested the need for vocal leadership, “(Latinos) don’t have anybody to follow.”40

“This year I’m going to be quieter,” said Navarro as the 1999 season kicked off. The embattled pitcher revealed in an interview with Teddy Greenstein of the Chicago Tribune that he had undergone a change since making amends the previous December with his parents, from whom he had been estranged for at least six years.41 “Anger, Frustration. Feeling isolated,” said Navarro of his emotions the last two years with the White Sox. “Coming to the ballpark all angry. I was like ‘to hell with the world. I don’t care about anybody else.’ I was hurting myself and my job.”42 Despite his promise, not much changed for Navarro. He struggled on the mound, and took out his frustrations on teammates, reporters, and team brass. When Navarro was shelled for seven runs in 2⅓ innings in his first start of the season, second-year manager Jerry Manuel seemed resigned to a long season: “As long as Jaime’s here, he’s going to be a starting pitcher. I really don’t see him helping us in the bullpen.”43 Nonetheless, sportswriters called for Navarro’s banishment to the bullpen all season long. In late August the pitcher defiantly stated, “I’m not going anywhere. They had a chance to trade me and didn’t. Now they’re stuck with me.”44 A week later Navarro was in the bullpen, his fate with club all but sealed.

The Chicago press got its wish when the White Sox traded Navarro (8-13, 6.09 ERA) and right-hander John Snyder to the Milwaukee Brewers for another struggling pitcher, Cal Eldred (2-8, 7.79 ERA), and infielder Jose Valentin on January 12, 2000. After losing all five of his starts (12.54 ERA) with the Brewers, Navarro was released on April 30. He finished the season with a brief stop in the Colorado Rockies minor-league system, and made his final seven big-league appearances with the Cleveland Indians. In 12 seasons, Navarro fashioned a 116-126 record with a 4.72 ERA in 2,055⅓ innings.

Just 33 years old, Navarro was far from ready to hang up his spikes. He played in the Independent Atlantic League in 2001 and 2003, and also had short stints in the St. Louis Cardinals and Cincinnati Reds farm systems. From 2004 to 2006 he hurled for BBC Grosseto in the Italian premier league.

In 2008 Navarro transitioned into coaching. He had a three-year apprenticeship in Seattle’s minor-league organization as a pitching coach before returning to the big leagues from 2011 to 2013 as bullpen coach for the Mariners. The next two years he was the pitching coach for their Triple-A affiliate, the Tacoma Rainiers. In 2016 he served as pitching coach for the Pericos de Puebla in the Triple-A Mexican League.

As of 2016 Navarro spent the offseasons in Orlando, Florida. He has two children, Jaime Jr. and Jaycee Lynn, whose mother, Tamara Weber, he divorced at the end of his playing career.

After a playing career that often consisted of either highs or lows, but rarely a middle ground, and a contentious relationship with the media, Navarro had lost none of his passion for the game. “Be patient,” he once said to describe his coaching style. “Baseball’s not all on the field. We’re all human. I want to pass on what I know so the young pitchers will be better than I was, not make the same mistakes when I was young.”45

Last revised: August 1, 2018

This biography is included in “Puerto Rico and Baseball: 60 Biographies” (SABR, 2017), edited by Bill Nowlin and Edwin Fernández.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com, and The Sporting News archive via Paper of Record.

Notes

1 The author expresses his sincere gratitude to SABR member Rory Costello, who interviewed Ana Cintron de Navarro on June 17, 2016, for this biography. Mrs. Navarro offered insights to Jaime Navarro’s childhood and introduction to baseball.

2 Mike Kiley, “Navarro: A Highly Charged Hurler,” Chicago Tribune, September 11, 1996: 10.

3 Scouting report for Navarro courtesy of Diamond Mines at the Baseball Hall of Fame. https://scouts.baseballhall.org/report?reportid=04719&playerid=navarja01.

4 Information according to Ana Cintron de Navarro. Interview by Rory Costello on June 17, 2016.

5 Ibid.

6 Cliff Christl, “Brewers Stumble Over ‘Little Things,’” Milwaukee Journal, June 21, 1989: 1C.

7 The Sporting News, August 21, 1989: 19.

8 Mike Stephenson, “A Winning Attitude. Brewers Navarro Eager to Learn Himself,” Milwaukee Journal, August 4, 1989: 1C.

9 “Keeping Quiet About Navarro,” Milwaukee Journal, May 14, 1990: C4.

10 Frank Clines, “Navarro Finishes What He Starts,” Milwaukee Sentinel, August 24, 1990: C1.

11 Tom Haudricourt, “Navarro Looks for Quick Start,” Milwaukee Sentinel, March 1, 1991, Part 2, 3.

12 Tom Haudricourt, “Navarro’s Four-Hitter Halts Tribe,” Milwaukee Sentinel, May 25, 1991, Part 1, 2.

13 Tom Haudricourt, “Navarro Slams Door on Seattle,” Milwaukee Sentinel, June 21, 1991: 1B.

14 Tom Haudricourt, “Navarro Blanks Indians,” Milwaukee Sentinel, July 28, 1992: 1B

15 Ibid.

16 Ibid.

17 Tom Haudricourt, “Navarro Wipes Slate Clean,” Milwaukee Sentinel, September 2, 1993: 1B.

18 Tom Haudricourt, “Vintage Navarro Would Fill the Bill,” Milwaukee Sentinel, March 17, 1994: 1B.

19 Ibid.

20 Tom Haudricourt, “Scanlon Replaces Navarro as Starter,” Milwaukee Sentinel, June 2, 1994: 2B.

21 Joseph A. Reaves, “Navarro Signing Probably Last Major League Move,” Chicago Tribune, April 10, 1995: 2.

22 Joseph A. Reaves, “Lighter Navarro Looks Forward to Brighter Tomorrow as Starter,” Chicago Tribune, April 11, 1995: 5.

23 Joseph A. Reaves, “Quiet New Cub Could Make Noise,” Chicago Tribune, April 24, 1995: 8.

24 Joseph A. Reaves, “Navarro Latest Cub King of the Hill,” Chicago Tribune, July 9, 1995: 3.

25 Bob Verdi, “To His Teammates, Navarro Is Way Behind the Count,” Chicago Tribune, May 29, 196: 1.

26 Gene Wojciechowski, “Navarro Tapes Reveal Flaws,” Chicago Tribune, April 24, 1996: 3.

27 The Sporting News, June 3, 1996: 23.

28 Verdi.

29 Mike Kiley, “Cubs 11, Mets 1. Navarro Stays on Second Half Roll,” Chicago Tribune, August 13, 1996: 3.

30 Mike Kiley, “Navarro: A Highly Charged Hurler,” Chicago Tribune, September 11, 1996: 10.

31 Gene Wojciechowski, “Slimmed-Down Navarro for Home Opener,” Chicago Tribune, March 31, 1996: 8.

32 Mike Kiley, “MacPhail Says Deals Should Be Compared Only to Division Foes,” Chicago Tribune, December 13, 1996: 4.

33 Gene Wojciechowski, “Bargain Pickup Mulholland Earns Respect, Admiration From Cubs,” Chicago Tribune, May 18, 1997: Part 3, 15.

34 Bernie Lincicome, “Indifference, Hangs Heavy Over the Sox,” Chicago Tribune, July 27, 1997: Part 3, 1.

35 The Sporting News, August 25, 1997: 46.

36 Teddy Greenstein, “Tigers 6, White Sox 0. ‘We Stink,’ Says Navarro.” Chicago Tribune, May 31, 1996: 3.

37 Teddy Greenstein,” Red Sox 15, White Sox 14. Eight-Run Inning Can’t Save White Sox in Messy Marathon,” Chicago Tribune, July 6, 1998: 1.

38 The Sporting News, September 12, 1994: 6.

39 Gene Wojciechowski, “Finding Tonic for Scandal as Close as Your Team.” Chicago Tribune, May 25, 1997: Part 3, 15; Fred Mitchell, “Don’t Fix the Bulls Until the Break, Thomas Advises,” Chicago Tribune, June 5, 1997: Part 4, 8.

40 Gene Wojciechowski, “Hand Surgery to Knock Out Magadan at Least a Month,” Chicago Tribune, March 11, 1996: 3.

41 Teddy Greenstein, “Parents Tough Love Lifts Navarro. Sox Pitcher Ends Estrangement, Learns Humility,” Chicago Tribune, May 18, 1999: 8.

42 Ibid.

43 Jimmy Greenfield, “Despite Getting Shelled, Navarro Won’t Be Shelved,” Chicago Tribune, April 11, 1999: 3.

44 Teddy Greenstein, “Navarro: Forget Bullpen. They’re Stuck With Me,” Chicago Tribune, August 31, 1999: 8.

45 Karen Westeen, “Q&A with Tacoma Rainiers Jaime Navarro,” Tacoma Sports Weekly, May 4, 2000.

Full Name

Jaime Navarro Cintron

Born

March 27, 1967 at Bayamon, (P.R.)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.