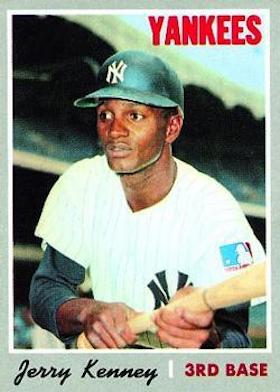

Jerry Kenney

Like many New York Yankees from their late 1960s and early 1970s nadir, Jerry Kenney suffered from the curse of expectations that media and fans had for the once dominant franchise. Winning 29 pennants and 20 World Series in 44 years, from 1921 to 1964 inclusive, was proof to many fans that winning was an entitlement. However, the team swiftly declined with three straight losing-record seasons from 1965 through 1967 and was barely above .500 in 1968. This set the stage for 1969, when Kenney would begin his first full season in the major leagues with a particular burden of expectations that would turn quickly to mockery.

Like many New York Yankees from their late 1960s and early 1970s nadir, Jerry Kenney suffered from the curse of expectations that media and fans had for the once dominant franchise. Winning 29 pennants and 20 World Series in 44 years, from 1921 to 1964 inclusive, was proof to many fans that winning was an entitlement. However, the team swiftly declined with three straight losing-record seasons from 1965 through 1967 and was barely above .500 in 1968. This set the stage for 1969, when Kenney would begin his first full season in the major leagues with a particular burden of expectations that would turn quickly to mockery.

Born on June 30, 1945, in St. Louis, Kenney spent the majority of his youth in Beloit, a Wisconsin town northwest of Chicago. Growing up there, his primary sport was basketball, winning All-State honors in his senior year of high school.1 However, Kenney chose to pursue the opportunities of professional baseball. Signed by the Yankees as an amateur free agent before the 1964 season, Kenney advanced steadily through the minors as a shortstop with a skill set based on contact hitting, speed, and fielding that was undercut by minimal power. After a successful cup of coffee with the Yankees at the end of 1967, an OPS+ of 146 in 20 games, team expectations were for Kenney to open camp the next year as the presumptive starter at shortstop.2 During that offseason, Kenney was rated as the Yankees’ “best player in the minor leagues,” meaning the team was all the more dismayed to learn in November that he would have to serve two years in the Navy to meet his service obligations during the Vietnam War.3 However, in November of 1968, just as the team was denying reports of Mickey Mantle’s retirement, it was announced that Kenney was being released early from military service.4 These simultaneous press releases were a first coincidental link between Jerry Kenney and Mickey Mantle.

Attempts to directly link Kenney with Mantle, and the accompanying legacy of DiMaggio and Combs, would begin early in 1969. Commencing in January within The Sporting News, “In any discussion of the 1969 Yankees, the most prominent names are Bobby Murcer and Jerry Kenney.”5 By February, it was public knowledge that the Yankees were preparing to move Kenney from shortstop to the outfield.6 Manager Ralph Houk praised Kenney and Murcer as the “fastest runners the Yankees ever had.”7 To this point in time, the public perception operated on the assumption that Kenney was simply joining a team with Mantle on it, rather than replacing him.

On March 1 Mickey Mantle officially announced his retirement. Mantle’s delay since the end of the prior season was in accordance with the wishes of both Marvin Miller,8 executive director of the players’ union, and the Yankees.9 The hype of Kenney, who had not played a regular season game in the major or minor leagues since 1967, intensified. George Vecsey of the New York Times proposed that the presence of Kenney among the “fine young prospects” on the Yankees lessened the need for Mantle in the lineup.10 Within a couple of days, an Associated Press article began making the rounds of the nation’s sports pages. The author, Mike Rathet, emphasized the connection between Kenney and the departing Mantle, noting that both transitioned from shortstop to center field upon entering the majors. As newspaper editors around the country varyingly titled the article, the suggestions became blatant. The least leading, without a titular reference to Mantle, was the relatively simple take of the Beacon (New York) Evening News: “Jerry Kenney Gets Chance for Yanks Center Field Job.”11 “Jerry Kenney Groomed for Mantle’s Job” was how the article encouragingly ran in Oswego, New York.12 The upstate New York Leader-Herald ran the article under the title of “Yanks to Give Kenney Short at Retired Mantle’s Outfield Job.”13 In Nashua, New Hampshire, the title suggested the sanction of experts with “Jerry Kenney Seen as Mantle’s Replacement.”14 Finally, the Gettysburg (Pennsylvania) Times opted for the blunt “Jerry Kenney to Replace Mantle in Center Field.”15 The connection between Mantle and Kenney was manifest. Although Mantle primarily played first base in his final seasons, the article titles indicate that the popular conceptualization of Mantle was still as the center fielder he had been in his prime.

More original articles followed. According to the Cleveland Plain Dealer, the Yankees’ problem that year was in finding who could fill the hole left by the departing Mantle: “They hope the someone could be Kenney.”16 The Reading (Pennsylvania) Eagle reminded its readers of the obvious parallel between Mantle’s shift to first base two years prior and Kenney’s move to center field.17 Two and a half weeks before the season, Kenney’s name was among the other Yankee youngsters as having been given a “shot in center field, the old stamping ground of Mantle and DiMaggio” and, more specifically, the opportunity to “someday be as known as Mantle.”18 For a player who had missed the entirety of the previous season, and had only a month in the major leagues before that, articles like these would form the basis of public knowledge regarding Kenney.

For the Yankees, center field was the position of glory for Hall of Famers Mantle, Joe DiMaggio, and Earle Combs, a lineage that stretched back to 1924. Moreover, Kenney would be the first to play center field after Mantle’s retirement. Far from being the only Yankees player burdened with high expectations, Jerry Kenney was one in a series of attempts by the team and its media at presenting new players as connections to the team’s prior success. Among Yankees prospects from the 1960s, and apart from Kenney, Ron Blomberg,19 Bobby Murcer,20 Joe Pactwa,21 Joe Pepitone,22 Roger Repoz,23 Bill Robinson,24 Tom Tresh,25 Steve Whitaker,26 and Roy White,27 all were posited as heirs to Mantle. When then-manager Bill Virdon moved him from center to right field in 1974, Bobby Murcer maintained his anger over the seeming demotion for years.28 Though the lineage of Hall of Famers at the position ended with Mantle, there are continued efforts by the press to propose more modern links to this aspect of Yankees history. As Johnny Damon in 2005,29 Brett Gardner in 2008,30 and Curtis Granderson in 201231 experienced, the passage of decades did not preclude attempts to associate players with their forebears on the team.

In his early returns, Kenney did not disappoint. A strong training-camp performance won him a share, with pitcher Bill Burbach, of the James P. Dawson award, given to the best performance by a Yankee rookie in his first major-league spring training.32 On Opening Day, Kenney continued his strong spring training by hitting a homer and double to lead the Yankees to a win in Washington with President Nixon in attendance.33 Just a few days after that, Kenney was noted as part of “possibly the best young outfield in the majors.”34 This moment, early in the 1969 season, would constitute the peak for Kenney in New York.

Kenney’s hot start would not continue. A last highlight before the oncoming realization of his limitations came on May 3. The thousands of children on hand for the annual free-cap day cheered as Kenney made a leaping catch in deep center to steal an opposing base hit. The New York Times noted the rare sight of a Yankee center fielder performing acrobatics in the field –given the latter-day “weak legged” Mantle and the inability of his replacements before Kenney.35 Despite Kenney’s defensive highlight, the Yankees lost. Further, Kenney had only one hit, which was yet sufficient to raise his season batting average to an anemic .206. The comparison between the fielding prowess of a young Kenney versus that of the aged and injured Mantle would be the final instance of the two sharing a context.

For the Yankees’ May 13 game against the expansion Seattle Pilots, manager Ralph Houk shifted his defensive alignment, swapping Kenney to third base and Bobby Murcer to center field. Though he was hitting well at the time, Murcer was disastrous at third, having already committed 14 fielding errors in only 32 games played. In contrast, Kenney fielded his position competently but hit worse than expected. Notably lacking in Kenney’s performance was any semblance of power. He slugged only .311 for the season, well below that year’s American League .369 average or the .398 that even a diminished Mantle managed the season prior. Also contributing to Houk’s willingness to reassign positions on the team was the fact that the Yankees were in the midst of losing five straight games and 14 of their last 16. Despite the shift in alignment, the team’s trajectory did not alter as the Yankees fell to the Pilots again.36 At this point, the Yankees were 12-21 and 9½ games back of the division-leading, and eventual American League pennant winner Baltimore Orioles. Notably, the inaugural Pilots had one more win than the Yankees despite three fewer opportunities.

Jerry Kenney’s trial in center field was concluded; he would play the vast majority of the rest of his Yankee tenure at third base and not another inning in the outfield after 1969. There would be no more articles in the papers mentioning Kenney and Mantle together. It was only 116 days since the first hyping Sporting News article, 74 days since Mantle retired, and 72 days since the first article directly describing Kenney as a replacement for Mantle and link to the Yankee legacy of center fielders. To be fair, Kenney situation was not advantageous. His release from military service was in December of 1968. Thus, Kenney went 18 months without playing in a regular-season game – October 1, 1967, to April 7, 1969.37 Kenney was also required, after his extended absence from the diamond, to switch positions. Asked in 1969 about his performance in center field, he replied, “I don’t know if I did well as an outfielder because I never had done it before.”38 Kenney began the 1969 regular season with few favors granted.

After the 1969 season, the Yankees still held some hope for Kenney as a useful major leaguer. Manager Ralph Houk would praise the younger Yankees, “particularly impressed by the improvement and promise shown by such relatively new players” like Kenney.39 However, the tenor that post-hype coverage would take for Kenney was revealed by his absence among those Leonard Koppett of the New York Times titled as the Yankees’ “Stars in the Making.”40 Then Kenney’s performance plummeted in 1970 to a dismal .193/.284/.282 line. That batting average set a still-standing team record for hitting futility over as many games as Kenney played.41 In another season lowlight, Kenney would go hitless over eight at-bats in an 18-inning loss to the Washington Senators on April 22, tying a team record for failure at the plate in a single game.42 A change in batting style helped Kenney to rebound at the plate after that year,43 but his playing time began to dwindle – from a peak in 1970 of 140 games played to 120 in 1971, and only 50 in 1972. In the Yankees’ final game of 1972, Kenney was one of the “mess of mediocrity” to take the field in the last Yankees game before George Steinbrenner bought the team in early 1973.44

On November 27, 1972, the Yankees traded Charley Spikes, John Ellis, Rusty Torres, and Jerry Kenney to the Cleveland Indians for Graig Nettles and Jerry Moses. Primarily, the trade was centered on the Yankees’ acquisition of Nettles, who would be a five-time All-Star and two-time Gold Glove winner in New York.45 Reaction in Cleveland was mostly negative with Kenney separately described as a “journeyman”46 and a “throw-in.”47 Hal Lebovitz, in an article headlined “Four Guys Named Who?” noted fan disapproval of the trade running at 82 percent.48 Though not in response to fans’ initial disapproval, Kenney’s stint with the Indians would be a short one.

Having not been offered a salary increase by the Indians, as was customary for traded players, Kenney refused to sign and planned to play the 1973 season without a contract. His intent after the season was to sue for free agency – a challenge to baseball’s reserve clause that allowed teams, from their perspective, to retain the rights to players indefinitely.49 As with every other attempt before Dave McNally and Andy Messersmith’s successful pursuit of free agency after the 1975 season, this particular ploy was defeated by the teams. On May 4, after appearing in only five games with the Indians, Kenney was placed on waivers. Publicly, the Indians maintained that the timing was due to an impending deadline that, if passed, would have guaranteed Kenney’s salary for the entire season. Russell Schneider of the Plain Dealer, in his coverage of Kenney’s professional passing, acknowledged that the intention to test the reserve clause was “another motive in the Indians’ desire to release Kenney at this time.”50

With that release, Kenney’s major-league career was over at age 27 – only 465 big-league games played for a possible Mickey Mantle replacement. For comparison, Mantle, with a history of lingering injuries, played 2,401 games in his career. Kenney would find himself back with the Yankees organization later that summer, though only with their Triple-A Syracuse affiliate. “I know I can play in the majors,” said Kenney before 1974’s spring training.51 However, once in camp he was simply “retread Jerry Kenney” among other more promising players.52 Kenney would play out the entirety of the 1974 and 1975 seasons in Syracuse with his final release coming in 1976 when he was, due to his more expensive veteran status, released to make room for future major leaguer Mickey Klutts.53 Kenney’s career ended in the way most professional baseball careers end – not in the major leagues before a battery of cameras and an announcement to be carried in the newspapers, but with a personal decision aided by the realities of dwindling opportunities and team indifference.

After Kenney left baseball, the brief moments of hope that accompanied the dawn of his career were forgotten so that he could become a label for an underwhelming period of team history. Three years after he last played for the Yankees, Kenney was described, among other Yankees players of the era, as occasioning “derisive belly laughs.”54 The New York Times included the failures of Yankees prospects like Kenney as one of 50 reasons that would enable fans of other teams to understand the “unhappiness that even a Yankee fan must sometimes endure.”55 In 1981 George Vecsey, who reported on the team during and after Kenney’s tenure in New York, would say that he never fell for Yankees president Mike Burke’s attempts to sell Kenney’s abilities to the press.56 The 1989 edition of the Yankees struggled against their expectations and would be called out for bearing a “greater resemblance to the Yankees of the Horace Clarke-Jerry Kenney days than to the Yankees of Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Joe DiMaggio, Mickey Mantle and Reggie Jackson.”57 When he was promoted from radio to television coverage, Michael Kay proved his credibility as a Yankees fan by managing to “stay loyal even through the team’s Jerry Kenney era.”58

Similarly, Kenney would also serve as a benchmark, a touchstone for when other, later Yankees were underperforming against expectations. In 2011 a New York Post article advised Yankees outfielder Curtis Granderson to find a middle ground of performance between Kenney, among other listed failed Yankees center fielders, and Mantle.59 In 2012 Joel Sherman suggested that Yankees catcher Russell Martin was weakening his position in the coming free-agent market due to the “danger of making history, and not the kind any player wants to make”; the particular danger was how close Martin was to surpassing Kenney’s mark for the lowest batting average by a Yankees regular.60 Martin would pull his average up from .173 to .211 by season’s end and therefore avoid the ignominy of hitting as poorly as Kenney.

If he had managed to survive and succeed in center field, Jerry Kenney would have provided another chain in the link of Yankees history that traveled back from Mantle to DiMaggio to Gehrig to Ruth. Though he failed to thrive, he was generally considered a genial, talkative fellow for whom baseball was not the sum total of his existence. Even when cut by the Indians, he acknowledged their motives but claimed to feel no hostility. Similarly, when pressed on the possibility that his career might be over, that no team might be willing to pick him up, Kenney managed to be philosophical – “well, if nobody does, it won’t be the end of my life.”61 After his exit from baseball, he returned to New York to work in the recording industry and eventually retired to Beloit in the late 1980s. Since then, his connections to baseball have consisted of coaching an American Legion team and the occasional appearance at games of the local Beloit Snappers.62 Kenney’s failure, such as it was for a man who worked his way to his profession’s pinnacle for several years, was his inability to meet the labels and expectations prescribed by others.

Last revised: November 1, 2016

Notes

1 “Boys Basketball History, 1963,” Wisconsin Interscholastic Athletic Association, accessed September 18, 2016, wiaawi.org/Portals/0/PDF/Sports/Basketball_Boys/History/1960/1963.pdf.

2 Jim Ogle, “Thunder Gone, Yankees to Say It With Lightning Next Year,” The Sporting News, October 7, 1967: 34.

3 Joseph Durso, “Yanks Seek to Revive Glory of Past: Army Adds to Toll,” New York Times, November 5, 1967.

4 Leonard Koppett, “Bahnsen of Yankees American League’s Rookie of Year,” New York Times, November 20, 1968.

5 Jim Ogle, “Yankees May Shift Kenney to Garden,” The Sporting News, January 18, 1969: 44.

6 George Vecsey, “Yanks Plans Hinge on Mantle’s Play: Houk Eager for Star to Decide on His Status,” New York Times, February 28, 1969: 43.

7 Arthur Daley, “Radical Style Change.” New York Times, March 11, 1969: 55.

8 Miller requested that Mantle delay announcing his retirement so as to be able to include his name among those refusing to sign contracts as part of negotiations between the union and MLB on player pensions. Allen Barra, Mickey and Willie: Mantle and Mays, the Parallel Lives of Baseball’s Golden Age (New York: Crown Archetype, 2013), 362-363.

9 The Yankees preferred that Mantle delay his retirement announcement hoping to maximize season ticket sales. Leavy, The Last Boy (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2010), 281.

10 George Vecsey, “Mantle Retires From Baseball After 18 Years: Hitting Art Gone,” New York Times, March 2, 1969, 289-291.

11 Mike Rathet, “Jerry Kenney Gets Chance for Yanks Center field Post,” Beacon (New York) Evening News, March 3, 1969: 11.

12 Mike Rathet, “Jerry Kenney Groomed for Mantle’s Job,” Oswego (New York) Palladium-Times, March 3, 1969: 8.

13 Mike Rathet, “Yanks to Give Kenney Shot at Retired Mantle’s Outfield Job,” Gloversville (New York) Leader-Herald, March 3, 1969: 14.

14 Mike Rathet, “Jerry Kenney Seen as Mantle’s Replacement,” Nashua (New Hampshire) Telegraph, March 3, 1969: 10.

15 Mike Rathet, “Jerry Kenney to Replace Mantle in Center Field,” Gettysburg (Pennsylvania) Times, March 3, 1969: 11.

16 Tom Place, “Yankees Base Hopes on Unknowns,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 9, 1969: 44, 47.

17 Walter L. Johns, “Yanks’ Jerry Kenney.” Reading (Pennsylvania) Eagle, March 13, 1969: 36.

18 John G. Griffin, “Houk, Minus Superstar, Feels Yanks Can Be Flag Contender,” Reading Eagle, March 20, 1969: 40.

19 Blomberg titled a chapter in his autobiography “The Next Mickey Mantle.” Ron Blomberg and Dan Schlossberg, Designated Hebrew: The Ron Blomberg Story (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing LLC, 2006).

20 “Bobby Murcer, once heralded as the Yankees’ next Mickey Mantle, traded teams yesterday with Bobby Bonds, once touted as the Giants’ next Willie Mays.“ Murray Chass, “Move to Coast Club Shocks Outfielder,” New York Times, October 23 1974.

21 Pactwa was seen as the “most likely to succeed Mickey Mantle.” Bus Saidt, “Ralph ‘Good News’ Houk High on Yanks,” Trenton (New Jersey) Evening News, March 23, 1969: 55.

22 “What Houk saw was this: At first base – Joe Pepitone, the often disappointing heir to Mantle’s mantle as the Big Bomber.” Mike Rathet, “Houk Must Manage team Without Mantle’s Bat,” Glens Falls (New York) Post-Star, March 6, 1969: 17.

23 In 1965, after a strong start in the majors, Repoz was asked: “Well, how does it feel to be the next Mickey Mantle?” William J. Ryczek, The Yankees in the Early 1960s (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc, 2008), 210.

24 “But there are many who are betting that … he will rate as the best Yankee rookie since Mickey Mantle in 1951.” Jim Ogle, “Best Since Mantle? Could be Bill Robinson,” The Sporting News, April 15, 1967: 7.

25 “‘There’s a lot of pressure,’ Tresh said, ’when somebody says you’re supposed to be the next Mantle.’” Ryczek, 209.

26 “Whitaker was especially pathetic because he was one in a set of the ‘next Mickey Mantle’ series.“ Peter Kaplan, “Back in the Ballpark,“ Harvard Crimson, October 8, 1976.

27 One article about Roy White in 1970 was titled “Mantle’s Successor Quiet but Superb Craftsman.” Marty Ralbovsky, “Mantle’s Successor Quiet but Superb Craftsman,” Victoria (Texas) Advocate, June 2, 1970: 10.

28 Murray Chass, “On Baseball; To Break a Man’s Heart, Take Center Field Away,” New York Times, March 1 2005.

29 “Johnny Damon had barely arrived in New York when he found himself being anointed the next in the line of succession of great Yankees center fielders, the latest to take on the role that is widely viewed as the most glamorous in sports.“ Murray Chass, “It’s Damon’s Turn at Center of a Yankees Myth,” New York Times, December 27, 2005.

30 “Gardner, who batted .260 in 45 games at Class AAA last season, says he thinks he will get the chance to regularly play one of the most storied positions in baseball history.” Jack Curry, “DiMaggio to Mantle to Williams to … Gardner?” New York Times, March 24, 2008.

31 “(T)he chatter now is whether the 31-year-old can take his game to the next level and join the Yankee tradition of great center fielders.” Jen Slothower, “Curtis Granderson Not Intimidated by Yankees’ Great Tradition of Center Fielders After Raising Game in New York,” New England Sports Network, September 13, 2012.

32 “Kenney, Burbach Split Rookie Award.” The Sporting News, April 19, 1969: 24.

33 George Vecsey, “Yankees Score 8-4 Opening-Day Victory Over Senators Before 45,111 Fans: Attendance Sets Washington Mark,” New York Times, April 8, 1969: 52.

34 Don “Red“ Moul, “’Red’ Writes,” Red Hook (New York) Advertiser, April 24, 1969: 4.

35 George Vecsey, “Orioles’ 3 Homers Top Yanks, 5-4: M’Daniel Beaten,” New York Times, May 4, 1969: 367, 373.

36 Leonard Koppett, “Murcer Shifted to Outfield Post,” New York Times, May 14, 1969: 51.

37 Joseph Durso, “Country Boys Plant Victory Garden,” New York Times, November 24, 1968: 360.

38 Jim Ogle, “Kenney an Acrobat as Yanks’ New Third Sacker,” The Sporting News, April 11, 1970: 32.

39 Michael Strauss, “Yanks’ .500 Hope Goes Down Drain: Season Finale Canceled by Rain – Coaches Retained,” New York Times, October 3, 1969: 54.

40 Leonard Koppett, “Yankees Still Short on Glamour, but They’ve Got Possibilities,” New York Times, March 1, 1970: 183.

41 Joel Sherman, “Martin’s Slump May Cost Him Millions,” New York Post, July 7, 2012.

42 Bill Chuck, “Derek Jeter’s Historically Bad Friday Night,” Gammons Daily, May 5, 2014.

43 Jim Ogle, “Yanks’ White Angry Over Talk of Weak Arm,” The Sporting News, July 3, 1971: 15.

44 Paul White, “Yankees to Face a Different Kind of Change,” USA Today, February 12, 2004.

45 Suspiciously, then Indians general manager Gabe Paul joined the Yankees as part owner in January of 1973 after trading Nettles to his future team. Before being cleared for ownership, Paul would have to discuss the matter with the commissioner, Bowie Kuhn. Kuhn said afterward, “I’m not concerned in the least about any suspicion that people may have.” Joseph Durso, “Gabe Paul Of Indians Joins Yankees as a Part Owner: Midwest Flavor Dominates,” New York Times, January 11, 1973: 45-46.

46 Russell Schneider, “Indians Tout Spikes as Super Star of Future,” The Sporting News, December 16, 1972: 58.

47 Russell Schneider, “Schneider Around,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, November 28, 1972: 38.

48 Hal Lebovitz, “Four Guys Named ‘Who?’” Cleveland Plain Dealer, November 28, 1972: 37.

49 Russell Schneider, “Kenney Says He Will Test Reserve Clause,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 17, 1973.

50 Russell Schneider, “Kenney Is Cut, Duffy Returns,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, May 5, 1973: 97-98.

51 Jim Ogle, “Avoiding Bat Drouth [sic] Munson Goal for ’74,” The Sporting News, November 24, 1973: 40.

52 “Yanks Making Few Swaps This Year,” Greeley (Colorado) Daily Tribune, March 9, 1974: 14.

53 Bob Snyder, “Dedicated Klutts Surprises Chiefs, Yanks With Hitting,” The Sporting News, July 24, 1976: 33.

54 Paul Lomeo, “Yankee Haters to Suffer Again?” Utica (New York) Daily Press, April 8, 1975: 11.

55 Julian Auerbach, “It’s Not Easy Being a Yankees Fan,” New York Times, October 4, 1981.

56 George Vecsey, “Sports of the Times; The Gentleman,” New York Times, November 7, 1981.

57 Murray Chass, “Some of the Reasons Yanks Are So Bad,” New York Times, April 13, 1989.

58 Chris Smith, “The Yankees’ YES Man,” New York Magazine, March 18, 2002.

59 Charles Wenzelberg, “No Flip Flopping for Yankees Granderson,” New York Post, April 2, 2010.

60 Joel Sherman, “Martin’s Slump May Cost Him Millions,” New York Post, July 7, 2012.

61 Russell Schneider, “Kenney Is Cut, Duffy Returns,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, May 5, 1973: 97-98.

62 Jim Franz, “One Man’s Stateline ‘Kings of Cool,’” Beloit Daily News, April 30, 2011, accessed September 18, 2016, beloitdailynews.com/sports/local_sports/one-man-s-stateline-kings-of-cool/article_ae4affd7-f874-5dda-90b5-b9d9120790eb.html.

Full Name

Gerald Tennyson Kenney

Born

June 30, 1945 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.