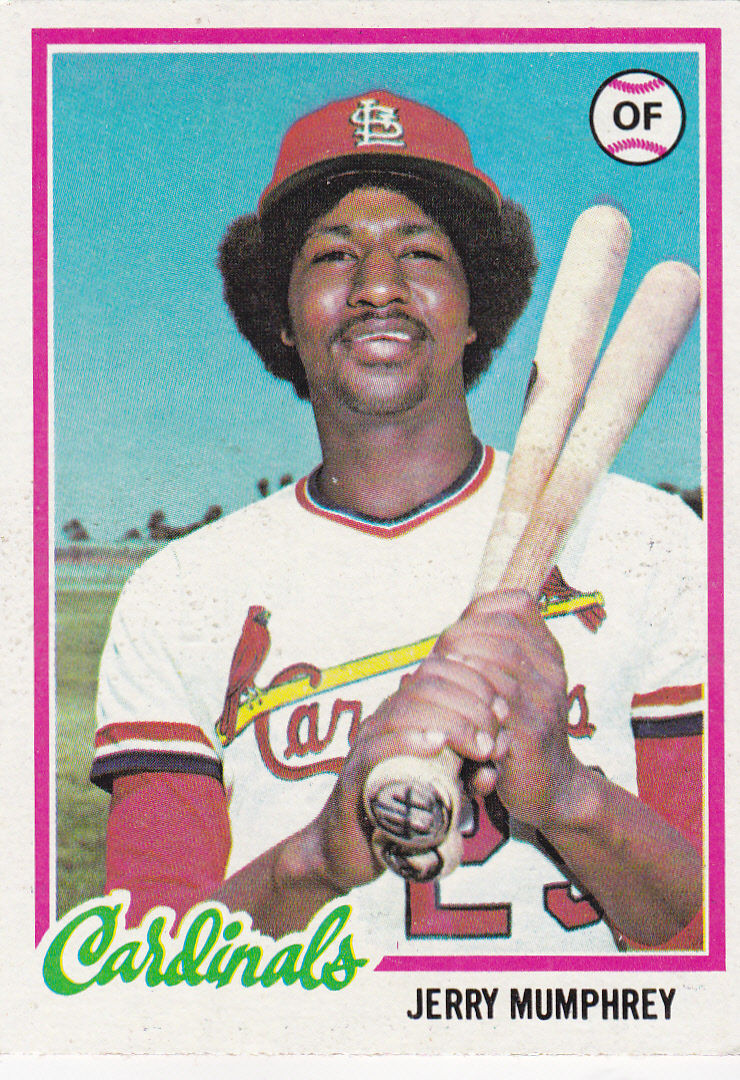

Jerry Mumphrey

“There is a lot of talk in the Cardinal clubhouse of togetherness … ’a family affair.’ Indeed, after each Cardinal victory, there blares a rendition of “We Are Family,” recorded by Sister Sledge … on the recommendation from reserve outfielder Jerry Mumphrey.”1 — The Sporting News

Unknown to many, Jerry Mumphrey’s name emerged to debunk a treasured association of the championship Pittsburgh Pirates as the sole team linked to the popular hit song of 1979. But Mumphrey’s career consisted of more than the disparaging of revered associations. Small-ball fans of any era would certainly appreciate the exploits of this fleet-footed athlete capable of tormenting an opponent in the following manner: “[Jerry] Mumphrey walked, stole second, moved to third on an infield out and scored on [a] sacrifice fly.”2 The ability to manufacture runs with explosive speed is testament to Mumphrey’s value during a 15-year major-league career (in spite of his unfairly derided defense), a value glimpsed when the switch-hitter was tabbed as one of the “names to remember … [in] whom the [St. Louis] Cardinals have high hopes.”3

Unknown to many, Jerry Mumphrey’s name emerged to debunk a treasured association of the championship Pittsburgh Pirates as the sole team linked to the popular hit song of 1979. But Mumphrey’s career consisted of more than the disparaging of revered associations. Small-ball fans of any era would certainly appreciate the exploits of this fleet-footed athlete capable of tormenting an opponent in the following manner: “[Jerry] Mumphrey walked, stole second, moved to third on an infield out and scored on [a] sacrifice fly.”2 The ability to manufacture runs with explosive speed is testament to Mumphrey’s value during a 15-year major-league career (in spite of his unfairly derided defense), a value glimpsed when the switch-hitter was tabbed as one of the “names to remember … [in] whom the [St. Louis] Cardinals have high hopes.”3

Jerry Wayne Mumphrey was born on September 9, 1952, in Tyler, Texas, the first of two children born to Roscoe and Evelyn (Wynn) Mumphrey. Tyler’s population nearly tripled in the six decades after Jerry was born, and the east Texas city (which calls itself the “Rose Capital of the World”) has produced a large number of professional athletes – primarily on the gridiron, the most famous being Pro Football Hall of Famer Earl Campbell. Mumphrey’s talents were sighted on the baseball diamonds at Chapel Hill High School in 1971. In his book The Scout: Searching for the Best in Baseball (co-written with Mike Capps), the late Expos recruiter Red Murff – a former major-league pitcher credited with discovering fellow Texan Nolan Ryan – described what the baseball world soon learned:

“Mumphrey would’ve fit Hollywood’s central casting ‘look’ for a major-league baseball prospect. Whippet-lean at six-two and about 175 pounds, he made me double-check my stopwatch the first time he hit the ball and ran to first. … He looked like Halley’s comet streaking down the line. … [L]uckily for me – or so I thought – I never saw another scout.”

Unfortunately for Murff, his windfall was shattered by the subsequent appearance of a San Francisco Giants scout that, with wagging tongues, begot other anxious eyes. In Mumphrey’s last game during his senior year, the stands were occupied with “more scouts than fans and parents!” With such intense interest, it is surprising that Mumphrey was not selected until the fourth round of the 1971 amateur draft until one recognizes its remarkable depth – Hall of Famers Mike Schmidt and George Brett were not chosen until the second round. Significantly, Mumphrey was snatched by the Cardinals after their third-round selection of another speedster, Larry Herndon. For the next four years (until Herndon was traded to the Giants) these youngsters’ minor-league development mirrored each other’s as they advanced from rookie-league play to Triple-A competition.

Mumphrey required little acclimatization to his new Florida surroundings as he hit at a .353 clip in his first ten appearances in the Gulf Coast League. Slowed to six hits in 41 at-bats as the short season closed, he resumed his torrid pace the next year with a combined .314 mark along three stops. Assigned to St. Petersburg in the Class A Florida State League in 1973, he led the circuit in hits and runs scored as he and Herndon produced nearly identical batting lines – Mumphrey .286-5-52 with 28 stolen bases, Herndon .287-3-41 with 41 stolen bases (placing both among the league leaders in base thefts). Mumphrey received his first invitation to the Cardinals’ training camp the following spring accompanied by an encouraging appraisal published in The Sporting News: “Mumphrey and Herndon stood out at St. Petersburg (Florida State) last season. … Mumphrey, ticketed for left field, is not as [proficient] in the field as Herndon, but he hits the ball more sharply.”4 Promising as this assessment was, left field was hardly vacant with Lou Brock only two-thirds along in his Hall of Fame career.

Unsurprisingly, the challenge of unseating Brock was too daunting and Mumphrey, along with Herndon, was assigned to the Double-A Arkansas Travelers. The Texas League was of little challenge to the pair. Excluding home runs (neither possessed much power), the duo placed among the league leaders in nearly every offensive category, particularly (again) stolen bases – Herndon and Mumphrey placing one-two with 50 and 40, respectively (they also placed five-six in hits, this time with Mumphrey in the lead). Jerry’s hits appeared to come in bunches. On June 21 he had four (as did Herndon) including a home run in a 10-2 victory over the Shreveport Captains. A month later he collected six hits in two lopsided wins over the El Paso Diablos. Batting leadoff in the Texas League All Star Game, Jerry scored three runs on three hits in leading his squad to a 10-5 exhibition win over the Texas Rangers.

The success in Arkansas earned Mumphrey and Herndon a September 1 call-up, and the parallels between the two continued. They each made their debut in pinch-running roles while making but one appearance in the field (naturally on the same day) – Mumphrey replacing Lou Brock in left field in the seventh inning of a 19-4 rout at the hands of the Chicago Cubs. An error by the Cubs second baseman in the bottom of the seventh allowed Mumphrey to reach base in his first at-bat and he came around to score the Cardinals’ fourth tally. A groundout to third in the ninth represented his only other plate appearance. This, together with four pinch-running appearances, represented Mumphrey’s month-long introduction to the majors.

The spring training efforts of 1975 unfolded identically to the preceding year: the same day assignment of Mumphrey and Herndon to the minors, this time to the Triple-A Tulsa Oilers (American Association). The presence of these two speedsters plus another fleet-footed outfielder, Joe Lindsey, caused Oilers manager Ken Boyer to chirp that the team “may have the fastest outfield in baseball [albeit for a very short time – Herndon was traded to the Giants a few days after these words were uttered].”5 Mumphrey’s name again populated many of the statistical leader charts – including a league-pacing 44 stolen bases – that earned a second late-season call-up. He collected his first base hit and RBI in a ninth-inning pinch-hitting role against the Cubs on September 2. Twenty days later he made his first appearance in the starting lineup, playing right field in a 6-4 victory over the Montreal Expos. As the team took stock of its future during the offseason, the observations of Mumphrey by Cardinals management included these: “Switcher with good minor league credentials … Excellent fielder … Very coachable … [and unfortunately] Could be ready to step in as No. 1 spare outfielder.”6 The parent club apparently was not ready to consider the 23-year-old prospect as anything more than a reserve player.

Any hesitation the Cardinals may have had in ushering Mumphrey directly into the starting lineup likely emanated from the team’s offensive makeup. For two consecutive years the team ranked among the National League leaders in batting average, and the outfield trio of Brock, Bake McBride, and Reggie Smith contributed largely with consecutive .300 seasons. What the team lacked was power – last in home runs in 1974 and 1976, little better in between – and the addition of yet another solid contact hitter with great speed and little heft was not management’s preferred direction. Combined with a desire to see their prized prospect receive regular play instead of sitting behind the Brock, McBride, and Smith, they once again assigned Mumphrey to Tulsa. Injury and trade soon changed this.

A 13-for-23 surge propelled Mumphrey to an American Association-leading .338 average in statistics published through May 17, a date when he was already making his fourth appearance in a St. Louis uniform. A May 8 injury to McBride’s left knee landed him on the disabled list (and, in August, the surgeon’s table) and resulted in the recall of Mumphrey. While McBride attempted to play through the injury, another door soon opened for the youngster. Fearful of losing Reggie Smith to free agency at the end of the season, the Cardinals traded him on June 15 to the Los Angeles Dodgers. Thereafter, Mumphrey’s name appeared in the starting lineup in 65 of the club’s remaining 79 games. Making the most of regular play, he cracked his first major-league home run on September 17 against the Expos. He stole 22 bases (second on the club) and scored 51 runs. That winter he was assigned to the Culiacan club in the Mexican League in preparation for the following season.

The 1977 spring camp previewed what Mumphrey faced in his three remaining years with the Cardinals. The team had reacquired Ken Reitz to improve its defense at third base, but to keep Hector Cruz, the former incumbent, in the lineup, he was ticketed for an already congested outfield that also included a newcomer, center fielder Tony Scott, and McBride, healthy again. This trend continued year after year with the addition of, among others, Jerry Morales, George Hendrick, Dane Iorg, and Bernie Carbo. Mumphrey was relegated to part-time play. (His poor performances in the Grapefruit League – .122 in 1977; .152 in 1979 – didn’t help.)

Despite the constant competition, the Cardinals might have often thought of handing Mumphrey a regular starting position. His speed – despite inconsistent play – still placed him among the team leaders in stolen bases in 1977 and ’78. In 1977 he carried a .300 average into September and finished among the league leaders in triples. He was called one of the team’s “most pleasant surprises,”7 though not pleasant enough to prevent the acquisition of Morales that winter. In 1978 Mumphrey batted .298 after July 1. The Sporting News reported in February 1979 that throughout the offseason “there had been considerable pressure to deal Mumphrey. … [He] has been sought by several clubs.”8 Provided he wasn’t traded, Jerry appeared poised to take over right field.

Instead, a.152 average in Florida and a separated shoulder suffered while diving for a fly ball in an exhibition outing combined to produce another platoon scenario. Upset with the lack of play – 339 at-bats, the fewest since his 1975 September call-up – he made numerous requests for a trade. “I’m at the point in my career where I think I should be playing every day,” he said.9 Reports dubbed him the left-field successor to the 40-year-old Brock, but instead Mumphrey was involved in the first of two trades that landed him in San Diego for the 1980 season.

The Cardinals’ need for power was thought to be remedied by the December 7 acquisition of Cleveland’s Bobby Bonds in exchange for Mumphrey and pitcher John Denny. Meanwhile the Indians, seeking to bolster an aging, injury-riddled pitching corps, had long coveted Padres left-hander Bob Owchinko. With right field locked down by the free-agent signing of Jorge Orta, Cleveland swapped Mumphrey to San Diego for Owchinko and an outfield prospect. Uninhibited by platoon or injury, Jerry was granted the opportunity to finally show his mettle.

Despite the presence of slugger Dave Winfield, the Padres’ lack of offensive heft made the Cardinals look like Murderers Row. In 1980 San Diego hoisted a mere 67 home runs – 55 percent of them struck by Winfield and catcher Gene Tenace– and the last-place team was forced to produce runs via the basepaths, a means that played directly into Mumphrey’s strength. A muscle strain in his right leg suffered at the end of spring training initially slowed his progress – six stolen bases entering June – but he soon began averaging a base theft in nearly every other appearance while also striking the ball at a .313 clip. His career-high 52 swipes placed among the league leaders while contributing to a team record 239 steals (through 2013 they were the only NL club to boast three players – Mumphrey, Gene Richards, and Ozzie Smith – with 50 thefts in a single season). From June 3 to August 21 Mumphrey stole 27 bases without being thrown out, another club record. “I knew going to San Diego was a golden opportunity,” he said after the season. “Manager Jerry Coleman had confidence in me. He helped me develop confidence in myself.”10 While establishing career highs in plate appearances (622), at-bats (564), and hits (168), his value was exhibited in yet another manner.

Critics have often pointed to the large number of errors committed by Mumphrey and concluded he was a defensive liability – in both 1980 and 1981 he was the league leader in miscues by an outfielder. But these numbers tell only part of the story. His speed served as more than just an offensive tool; it allowed him to get to balls that a less agile player would not, an indication that the errors were often the result of his aggressiveness in the field. In 1980 he placed among the league leaders in outfield putouts; two years earlier he had placed second in the National League in fielding percentage. For five years beginning in 1976, Mumphrey was also among league leaders for assists as a center fielder. Perhaps the best indication of his value is the manner in which he was assessed by his peers and the press. Scribes asserted that his acquisition “solved the Padres’ defensive problems in center field,”11 that his ability served to “plug a defensive leak that drew constant complaints from San Diego pitchers last season.”12 Coleman was said to be “pleased with … the way Mumphrey has played center field,”13 and reliever Rollie Fingers referred to him as “one of the four or five best outfielders in the National League.”14 Mumphrey’s error totals prevented him from receiving Gold Glove consideration, but he was far from a defensive liability. In the midst of a threatened housecleaning, the Padres center-field post appeared to be safely in Mumphrey’s hands. This prediction did not take into account the arrival of general manager Jack McKeon.

Trader Frank Lane from earlier generations appears like an amateur when one examines the Padres after McKeon got his hands on them – he moved 37 players over a six-month span beginning August 1980. Mumphrey joined this large contingent on March 31, 1981, as part of a multiplayer swap with the New York Yankees. Three months earlier the Padres had lost Winfield to free agency when he signed with the Yankees, and San Diego feared a similar departure once Mumphrey became eligible for free agency after the 1981 season (his agent, Tom Reich, claimed the bidding for his client would begin at $800,000). The trade meant that for the first time in the majors, Mumphrey would play for a winning club, and he was ecstatic. New York was similarly pleased to add Jerry’s speed, a necessary component for roaming Yankee Stadium’s spacious center field, and he was soon lauded as the team’s “best center fielder since Mickey Rivers.”15

Probably nobody welcomed the 1981 midseason stoppage less than Jerry Mumphrey. When the season abruptly halted on June 11, the Yankees held first place, due largely to Mumphrey’s .322 pace. The two-month layoff affected Mumphrey little. He finished with his first .300 season (though far fewer stolen bases, 14 – a commodity not necessary with the hard-hitting New York club). Mumphrey’s work for the playoff-bound Yankees earned him a handful of votes as the league’s Most Valuable Player. An injury in mid-September threatened his chances of participating in his first postseason play, but he rebounded sufficiently to take the field October 7 in the strike-expanded playoffs. Mumphrey’s contributions – particularly in the second-tier playoff series against the Oakland A’s where he went 6-for-12 with two runs scored – helped vault the team into the World Series, where they lost to the Dodgers.

The warm feelings generated by the Yankees’ success resulted in a five-year, $3 million contract for Mumphrey in 1982. Those warm feelings turned icy before the end of the season. A 79-83 collapse led owner George Steinbrenner to lash out, spurred by his desire to unload some of the team’s higher salaried players. Mumphrey was one such target. Dismayed by accusations of not being tough enough, not being a team player, the player who had just completed his second consecutive .300 campaign replied: “I guess I’m not controversial enough.”16 As the verbal attacks continued into 1983, Mumphrey was rumored in trades to San Francisco, Chicago, and Atlanta. A slow start batting right-handed against lefties – a career-long issue that was only exacerbated by the Steinbrenner onslaught – resulted in a center-field platoon and an unhappy Mumphrey, a situation that his agent was soon able to remedy.

Mumphrey was not the only unhappily platooned center fielder in Tom Reich’s stable that season. The honeymoon between free-agent signee Omar Moreno and the Houston Astros was short-lived, and Reich was able to step in and construct an August 10, 1983, trade of his unhappy clients. Restored into a starting role with the Astros, the contented Mumphrey was able to show his pleasure with the bat – a .336 average in 143 at-bats that mushroomed into his only All-Star Game appearance the next year. When injuries decimated the Astros in 1984, the 31-year-old Mumphrey, no slugger, was often found in the unfamiliar role of cleanup, where his nine home runs placed second among the team leaders.

The team’s lack of heft caused the Astros to turn to Kevin Bass as their primary center fielder in 1985. Mumphrey, who earned most of his time in right, was forced to share that position with nine others. Slowed by injury, he had fewer than 500 plate appearances. On December 16 he was traded to the Chicago Cubs.

For the next three years Mumphrey was a platoon outfielder and pinch-hitter for the Cubs. In 1987 Mumphrey carved a fine reputation as a pinch-hitter, placing among the league leaders with a .343-2-12 batting line in 41 plate appearances. But from 1986 through 1988 he had fewer than 700 at-bats. On September 30, 1988, he came to the plate in what became his last major-league appearance and grounded out to the Pittsburgh Pirates second baseman. Two months later he was released. A player credited by 25-year-old teammate Shawon Dunston with helping him mature as a hitter turned his back on any possibility of coaching and returned to his east Texas hometown.

While playing, Mumphrey had shown a nose for business, investing with former Yankee Bobby Brown in an Atlantic City company that sold dairy products in ballparks across the country. He also got involved in an engine-repair business in Tyler – aptly named Home Run Small Engine Repair – that kept him busy for many years. In June 2012 Mumphrey celebrated 40 years of marriage to the former Gloria Stine. They had a son Jerron, who inherited some of his father’s athletic skills on the collegiate diamonds, and a daughter, Tamara.

The switch-hitting Mumphrey had far more success batting left-handed than right-handed (.303 vs. .256) in the major leagues. “He had trouble hitting a ball barely through the infield right-handed,” said George Kissell, general manager Bing Devine’s chief deputy with the Cardinals in 1976.17 In his later years Mumphrey appeared to have abandoned switch-hitting and batted right-handed, and the big difference in averages raises the question of how much more productive he might have been as an exclusively left-handed hitter.

A fine hitter regardless, Mumphrey was a beloved teammate and a press favorite for many years. He was described throughout his career as quiet, affable, and unassuming – the latter being most evident when, after being selected to the National League All Star squad in 1984, he said, “It’s a thrill, but there were others on our team who deserved to be chosen.”18 Perhaps Mumphrey’s true mettle shone through when teammates Garry Templeton and Leon Durham struggled with personal issues in 1981 and 1988, respectively and Mumphrey reportedly stood by both these troubled individuals – a strong indication that We Are Family was of great importance to this fine individual.

Author’s Note

The author wishes to thank Lisa Smith-Curtean, a volunteer at the West Waco (Texas) Library and Genealogy Center, for her helpful support researching the 1940 census, and Len Levin for editorial and fact-checking assistance.

Sources

The Sporting News

sabr.org/bioproj/person/c0764912

sabr.org/bioproj/person/29bb796b

US Census Bureau, 1940 Census

Notes

1 “Year of the Cardinals? Birds Pack Real Wallop,” The Sporting News, June 23, 1979, 3.

2 “National League: Games of Saturday, Aug. 14,” The Sporting News, September 4, 1976, 18.

3 “Quick Bake a Tasty Treat on Cardinal Table,” The Sporting News, April 12, 1975, 23.

4 “Cards’ Speed Demons Learning From Brock,” The Sporting News, November 24, 1973, 41.

5 “American Assn.,” The Sporting News, May 10, 1975, 36.

6 “’76 Cards Could Have Home-Grown Look,” The Sporting News, December 20, 1975, 50.

7 “Cardinal Stat Sheet Tells Two Types of Tales,” The Sporting News, December 17, 1977, 54.

8 “’Cards to Be Heard From’ – Bing’s Cheery Farewell,” The Sporting News, February 10, 1979, 38.

9 “Tribe Deals Rapped: Paul Replies,” The Sporting News, December 29, 1979, 33.

10 “Mumphrey to Shoot for More Power,” The Sporting News, January 17, 1981, 35.

11 “Mumphrey Bat Builds a Fire in Padres’ Attack,” The Sporting News, April 12, 1980, 38.

12 “Pitchers Boost Padres to a Flying Start,” The Sporting News, May 3, 1980, 9.

13 “None of Padres Will Rust On Bench, Vows Coleman,” The Sporting News, April 26, 1980, 18.

14 “Jack’s Many Trades Shock Padres,” The Sporting News, April 18, 1981, 29.

15 “Koosman Cites Principle in Bar Bill,” The Sporting News, July 25, 1981, 8.

16 “’Get Tough,’ George Urges Mumphrey,” The Sporting News, December 6, 1982, 50.

17 “Kissell Clicks Heels Over Card Kids,” The Sporting News, October 9, 1976, 17.

18 “Reynolds Is Super As Fill-In for Thon,” The Sporting News, July 23, 1984, 23.

Full Name

Jerry Wayne Mumphrey

Born

September 9, 1952 at Tyler, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.