Joe Cicero

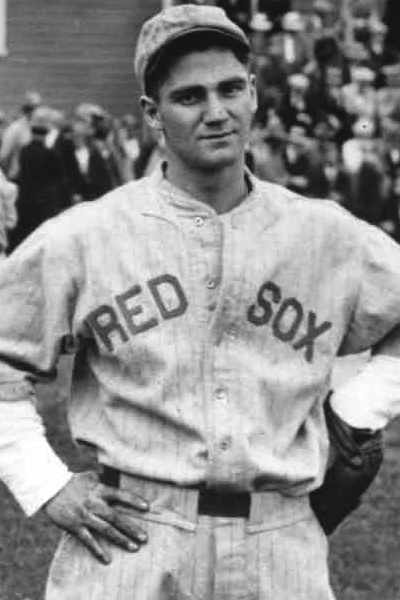

Joe Cicero had everything going for him. The Atlantic City, New Jersey, native led his Holy Spirit High School football team in scoring in each of his first three years at the school (two of which saw the squad undefeated), led the basketball team in scoring in each of his first three years, and led the baseball team in scoring in each of his first three years. Not only that, he was Clark Gable’s cousin – his mother’s sister was Gable’s mother, and Cicero himself was not bad looking himself, to judge from his picture on the baseball-reference.com website.

Joe Cicero had everything going for him. The Atlantic City, New Jersey, native led his Holy Spirit High School football team in scoring in each of his first three years at the school (two of which saw the squad undefeated), led the basketball team in scoring in each of his first three years, and led the baseball team in scoring in each of his first three years. Not only that, he was Clark Gable’s cousin – his mother’s sister was Gable’s mother, and Cicero himself was not bad looking himself, to judge from his picture on the baseball-reference.com website.

It was baseball that kept Joe from graduating from high school. He dropped out near the end of his senior year, six months after turning 17, and accepted an offer to travel to spring training with the Boston Red Sox. And it wasn’t his first time playing for pay. In the summer of 1927, he had played shortstop for a team in Easton, Maryland, in the Eastern Shore League under an assumed name (hoping to preserve his eligibility in school). He somehow acquired the nickname Dody while playing sandlot ball, and so, he told Baseball Hall of Fame historian Lee Allen, he adopted a similar-sounding name: Joe Doughty.[1] You could look it up; “Doughty” appeared in 62 games for the Easton Farmers, hitting .329 with a team-leading 13 home runs. One of the managers of the team was Jiggs Donahue, who had played for the Red Sox in 1923. Chances are that this is what led to the Boston connection.[2]

Cicero, of Italian and German descent, was born on November 18, 1910. He never grew to be a large man. He stood 5-feet-8½ and listed his playing weight as 170 pounds. He was nothing if not self-confident, though, one would imagine – in his Hall of Fame questionnaire, he said he would have played professional football had he not played baseball. He may have been able to back that up. At least as late as 1942, he played some semipro football.

Baseball was Cicero’s main love, though, and he was certainly precocious. A story in the Atlantic City Press after his death said he played for the high-school varsity team when he was in the seventh and eighth grade, winning the team batting title while in the eighth grade.

After Cicero signed and left Holy Spirit High, the Red Sox took him to spring training, where he hit home runs in back-to-back games and raised a number of eyebrows.[3] He stayed with the team until June 1, when the Red Sox sent him to the Salem Witches (New England League), considered to be the first acknowledged farm team the Red Sox ever had. There he appeared in 93 games under manager Stuffy McInnis (and under his own name), batting .285. He was recalled to the Red Sox in September, but saw no action. In the offseason he played professional football for the Atlantic City team. In 1929 he appeared in 151 games for the Pittsfield Hillies (Eastern League), playing both shortstop and outfield and hitting a very impressive .340 for manager Shano Collins, with real home run power — 25 round-trippers, accompanied by 12 triples and 33 doubles. He was fourth in the league in runs batted in and third in home runs. He finished with a bit of a flourish, hitting a perfect 8-for-8 in a September 10 doubleheader against Providence. It surprised no one when the Red Sox gave Joe a look in the big leagues in late September.

Cicero’s major-league debut took place on September 20, 1929; he hit a pinch-hit single in the seventh inning against the visiting Cleveland Indians. The next day he drew another pinch-hit role, and again singled against the Indians, this time in the bottom of the ninth. Cicero came around to score the tying run; Boston won it in 12. Joe’s best day was his 3-for-5 game on September 29 against the Philadelphia Athletics, when he drove in three runs. Altogether he appeared in 10 games, hitting .313.

Joe opened the 1930 season with the Red Sox, but never got on track with his hitting. He appeared in 18 games, the last one on June 24. He was hitting only .167 in 30 at-bats with three extra-base hits. Two days later, the Red Sox released Cicero and pitcher Frank Mulroney to Indianapolis. In 17 games playing for the Indians, Cicero didn’t fare much better (.171), and he moved a level down to Single-A ball playing for the Nashville Volunteers in the Southern Association. Cicero hit .287 at the lower level of play, was retained for 1931, and contributed a .331 average in 45 games. Most of the year, though, he played for the Three-I League’s Bloomington (Illinois) Cubs, hitting a solid .309.

After being signed by the Cincinnati Reds and spending much of the 1932 season with Peoria (.311), Cicero was “crippled” and voluntarily retired, but was reinstated by Commissioner Kenesaw M. Landis in February 1933.[4] He became part of the Philadelphia Athletics system for a while, playing for Williamsport in 1933 and 1934, before coming back to the Red Sox system with Scranton and then Reading later in ’34. His 42 stolen bases in 1933 set a league record. It might have been a little confusing in 1935, in that Cicero was assigned to four teams that had working agreements with the two Boston organizations (the Red Sox in Syracuse and Elmira and the Boston Braves in Harrisburg and Wilkes-Barre.) Almost all his playing time was for Harrisburg, where he hit .292.

Cicero started 1936 in the Phillies system, playing with Elmira (and leading the league in stolen bases with 30), then back in the Red Sox farm system with Hazleton (New York-Penn), where he opened 1937 before joining the Scranton Miners (Braves). While with Hazleton Cicero hit for the cycle on May 10, in a game in which his team scored 13 runs – but lost to Trenton, 25-13. He was released at the end of the month so the team could get down to the player limit. By then he had played for every team in the Eastern League except for Binghamton. Maybe this all just got too confusing, and he was really going nowhere fast. More likely, he just got a better offer. He played “outlaw ball” in 1938 and 1939, with St. Hyacinthe in Canada’s Provincial League (and played Canadian football later in the year.) In 1940, his third season with St. Hyacinthe, the circuit was reinstated to Organized Baseball. In 1941 Cicero he played a fourth year in Canada, for Quebec City in the Canadian-American League. Joe left baseball in 1942 and 1943, but it wasn’t to join the armed forces fighting in World War II. A problem with his vision rendered him exempt. It probably also ensured that he wasn’t quite the hitter he’d been. Joe also become tired of being shifted from club to club and so he retired from the game. He was married by this time – he’d gotten hitched in May 1931 to the former Helen Mary McDonald — and the couple had two daughters and a son.

Helen figured in an amusing anecdote in 1930. She and Joe knew each other, and she had given him a ring as a gift, which he wore on the little finger of his right hand, even while playing baseball. The Red Sox were playing the Yankees and Babe Ruth noticed the ring. He called out, “Hey, kid! You better not wear that ring in the game. If you ever smashed your finger, the ring would cut you.” Cicero says, “I told him that I knew I was taking a chance, but that it was a lucky ring. ‘Oh, well, if it brings you luck,’ Ruth said, ‘don’t take it off whatever you do.’”[5]

Nonetheless, Cicero kept active in sports, actually playing some semipro football again in 1942 and entering the Army for a year, despite his vision problems. In 1944 the New York Yankees were looking to bolster the war-depleted rosters of their farm system and signed Cicero to play for the Newark Bears at the recommendation of Atlantic City Press sports editor Whitey Gruhler. In his first game with Newark, Cicero had the most memorable day of what was already a long career, even though he was still only 33: He hit two grand slams and a two-run homer in a game on May 4 in Montreal, each one off a different pitcher, driving in 10 runs in a 17-8 Newark victory. That was the big splash; they were the only three homers he hit for Newark, and he drove in only one more run in the other eight games he played (batting .242). He ran into a fence and injured both knees; a back ailment and leg trouble were given as the reasons he “couldn’t recapture a semblance of a hit” after that, and he got his release.[6]

The next season, 1945, was Cicero’s last hurrah in Organized Baseball. The Philadelphia Athletics signed him on Valentine’s Day and took him to spring training, Earle Mack (an A’s coach and owner-manager Connie Mack’s son) murmuring, “If he can stand up at the plate and pinch-hit successfully now and then, he will be worth his salt.”[7] Now wearing eyeglasses, Cicero made the team and appeared in 12 games and batted only .158 – three singles in 19 at-bats. His last game with Philadelphia was on May 30. He was released and signed as a free agent with the Minneapolis Millers. He finished out his career there, batting .283 in 65 games. Then Cicero made a major move – to the Panama Canal Zone. He told Cooperstown historian Lee Allen, “My eyes had bothered me for years and I had put on glasses. I couldn’t hit much anymore. A fellow I’d played with in the minors told me I could get a job playing in Panama, so I came down here, liked the climate, got this civil service job on the canal and have been here ever since.”[8]

Cicero’s job was in security on the Panama Canal locks, and he worked there for three decades, until his retirement in 1976, when he and his wife moved to Clearwater, Florida. Son Joe and daughter Patricia stayed behind in Panama with their own families. Daughter Marie moved to Clearwater with Joe and Helen.

Cicero remained active in baseball while in Panama, playing winter ball in the Canal Zone League until 1952, when he was in his 40s. He worked as a scout for the Brooklyn Dodgers from at least 1952 until 1954. An article in the Pittsburgh Courier mentions him as the Dodgers’ scout for Central America, signing two “Negro Panamanians,” Clyde Parris and Wilfredo Holder (real name Wilfredo Moore).[9] Joe Cicero died at home in Clearwater on March 30, 1983.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Cicero’s player file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the online SABR Encyclopedia, Retrosheet.org, and Baseball-Reference.com, and the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball.

[1] The Sporting News, December 16, 1967

[2] Donahue is listed with Ted Cather as manager of the team in the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball.

[3] Chicago Tribune, March 14, 1928 & New York Times, March 15, 1928

[4] The Sporting News, February 23 and March 16, 1933

[5] The Sporting News, December 16, 1967

[6] The Sporting News, June 1, 1944 and February 22, 1945

[7] The Sporting News, February 22, 1945

[8] The Sporting News, December 16, 1967

[9] Pittsburgh Courier, March 1, 1952

Full Name

Joseph John Cicero

Born

November 18, 1910 at Atlantic City, NJ (USA)

Died

March 30, 1983 at Clearwater, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.