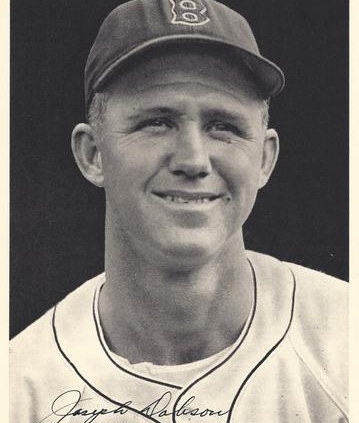

Joe Dobson

In the early years of the 21st century, the name of Joe Dobson, a right-handed pitcher who toiled for 10 years with the Red Sox, rarely crops up in discussions of the better Boston players of the past. Nonetheless, his 106-72 record places him ninth (through 2012) on the Red Sox all-time team list for wins and his .596 winning percentage has him in 13th place among those with 100 or more decisions. Leigh Grossman succinctly summarized his career: “never a great pitcher, but he was good and consistent for a long time.” The only category Dobson ever led his league in was wild pitches, but he was a key component in the pennant-winning year of 1946 and no Red Sox pitcher surpassed him over the following four years when Boston was regularly in contention.

In the early years of the 21st century, the name of Joe Dobson, a right-handed pitcher who toiled for 10 years with the Red Sox, rarely crops up in discussions of the better Boston players of the past. Nonetheless, his 106-72 record places him ninth (through 2012) on the Red Sox all-time team list for wins and his .596 winning percentage has him in 13th place among those with 100 or more decisions. Leigh Grossman succinctly summarized his career: “never a great pitcher, but he was good and consistent for a long time.” The only category Dobson ever led his league in was wild pitches, but he was a key component in the pennant-winning year of 1946 and no Red Sox pitcher surpassed him over the following four years when Boston was regularly in contention.

Dobson was a big pitcher for the day, 6’2” tall, with a playing weight of 200 pounds and a shock of wavy hair that earned him the nicknames “Burrhead” and “Curly.” Joe hailed from Oklahoma, born in the south-central farm town of Durant on January 20, 1917, a little more than nine years after Oklahoma became the country’s 46th state. The youngest of 14 children born to William and Lura Dobson, he moved with his family to Coolidge, Arizona, when Joe was 6 years old. William Dobson was a farmer who turned to carpentry in his later years. Midway between Phoenix and Tucson, it was in Coolidge that Joe was raised and where at age 9 or 10 he lost his left thumb and part of his forefinger in a childhood accident while inexpertly trying to blow up a rock with a dynamite cap a friend had found.

One of Joe’s brothers was a pretty good ballplayer, he recalled. “We’d play catch every day. He’d throw that ball so hard, my hands would hurt.”1 It was during his sophomore year in high school that he began to play baseball. “Before that time I had been content to do all my pitching at prairie dogs and such, just to improve my marksmanship and save money on ammunition.” He was helping his dad with carpentry outside of school when he read in the town newspaper that a Dr. Tremble was organizing a team in Tucson and looking for boys who would like to play baseball. He tried out and was added to the team. The first game he pitched, he beat Tombstone. The ballclub came together well and some of the businessmen put some money behind it, naming the team the Tucson Merchants. When Joe won the first game of a doubleheader during the July 1936 Arizona state tournament in Phoenix, he was approached by a Cleveland Indians scout, Grover Land, who asked Joe if he wanted to play pro ball. Joe’s feelings at the time reflect those of many: “I would have paid him to sign me up.” The Tucson team went on to Wichita for the national semipro tournament and Joe won a couple of games in the semifinals, but they couldn’t win it all. Land, though, landed Dobson and signed him to a contract with New Orleans, an Indians farm club in the Southern Association.

His first year in the Cleveland system was spent in Alabama with the Troy (Alabama) Trojans in the Alabama-Florida League under manager Charles Moss. Troy finished second in the six-team Class D league, while Joe posted a record of 19-12 with a 2.27 ERA, leading the league in complete games with 26. He struck out an even 200 batters, walking only 71. His work earned him a quick promotion all the way to the Class A Southern Association, where he pitched in 1938 for Larry Gilbert and the New Orleans Pelicans. At this elevated level, Dobson was 11-7 (3.29) in 178 innings of work. He made it to the major leagues to stay in 1939, beginning a career that took him right into the 1954 season.

Dobson was hardly a sensation in Cleveland, though. Things started well enough when he was called in to relieve on April 26 after Johnny Broaca had given up four runs to the White Sox in the third inning. Joe gave up three hits and no runs in five innings of work. Manager Ossie Vitt gave him a start four days later in Detroit. He pitched five innings in that game, too, but that didn’t go as well: Dobson was tagged for nine runs on 13 hits and lost the 14-1 ballgame. Joe appeared in 35 games, but largely in relief. He had just two more starts, one in June and one in August, and in those, too, the opposition scored into double digits, but the June loss was fully attributable to reliever Johnny Humphries. Dobson threw 78 innings and wound up with a 2-3 record and a 5.88 earned run average.

He pitched an even 100 innings in 1940, and showed some improvement. He ended the season 3-7, appearing in 40 games and recording an ERA of 4.95. The first game he started and won came against the Red Sox on July 21 at Fenway Park. He threw a complete-game, 2-0 shutout, allowing seven hits and walking three, inducing batters to hit into three double plays. Dobson’s work that day made an impression on Boston manager Joe Cronin. A few outings earned him recognition in the press, such as a one-hit, 5 1/3-inning stint on September 1 termed “brilliant relief pitching” by the Associated Press. Even though Vitt used him often, he felt overlooked. He realized he was, as he put it to Boston sports scribe Johnny Drohan, “just a ball player named Joe …. I couldn’t have been any more forgotten had I been a brother to King Tut. I did get in a few ball games but only after all the other pitchers on the bench had been knocked out of there.”2

A December 12 trade reported at the time as a three-cornered deal brought the pitcher named Joe to Boston. The Red Sox sent Doc Cramer to the Senators for Gee Walker, then traded Jim Bagby, Gene Desautels, and Walker to Cleveland and got Dobson, Odell Hale, and Frankie Pytlak. Dobson was happy to land in Boston. “Joe Cronin probably appreciated me more than the entire Cleveland organization,” he told Drohan.

With Bob Feller, Mel Harder, Johnny Allen, and Al Milnar in the rotation, it had been hard to break in as a starter with the Indians, but Dobson had a shot with the 1941 Red Sox as Lefty Grove’s career wound down, joining a Boston team with Dick Newsome, Mickey Harris, and Charlie Wagner among the other starters. Dobson showed “hustle and determination and stuff” in spring training in Sarasota.3 Ed Rumill of the Christian Science Monitor predicted early in spring training that “he may turn out to be one of the surprises of the…campaign.”4 For the 1941 season, Newsome won 19, and Wagner and Dobson were second with a dozen wins apiece. After losing his first start to the Tigers, Joe didn’t last long in his next start, on May 23, but the Yankee Stadium game ended in a 9-9 tie due to darkness. Six days later, he started and won a game against Philadelphia. It had taken him a while to get established, but he became a regular in the rotation and at one point reeled off a string of seven straight victories — something always sure to impress. That winter he could look back at a 12-5 season, with an improved 4.49 ERA, and know that he’d helped the Red Sox to a second-place finish.

Joe credited Frankie Pytlak and Jimmie Foxx with helping turn him around. Joe was 5-5 in mid-August and still struggling with his location when Pytlak told him one day, “Relax, don’t try to throw so hard and try to pick your spots around the plate.” On another occasion, Foxx said, “Take it easy, Joe. Let up a little. You don’t have to strike out every hitter.”5 Nothing special by way of advice, perhaps, but coming from Foxx and coming in a time when coaches rarely gave much real instruction to pitchers, it may have made the difference. Equally important may have been Ted Williams, who had hurt his foot and wanted to take some extra batting practice to help him come back. He asked Joe to throw to him and in the one-on-one pitching repeatedly to a .400 hitter, Joe may have become better able to harness his pitches and develop his control.6 Author Peter Golenbock added: “They would pretend it was a real game, and Dobson would throw his best. By the time he returned to the Boston lineup as an everyday performer, Williams’ batting skills were honed and sharp.”7 Entering 1942, Newsome, Wagner, and Dobson were the three starters on whom the Sox built their hopes. Joe won 11, lost 9, and cut more than a full run off his ERA, bringing it down to 3.30.

With World War II under way, players were starting to leave for military service. Hot rookie shortstop Johnny Pesky was gone, and Williams and Dom DiMaggio were in the service by 1943 as well. Dobson had a 3-A deferment with a wife (Marguerite Weiss) and young child in the family. He’d spent the winter working construction in his wife’s hometown of Nashville. The work kept him in shape and he had another good season on the mound (3.12 ERA), though the team’s having lost so many players contributed to a disappointing 7-11 record. The 1943 season started poorly, but after a tonsillectomy in midseason, Dobson came on strong and won six of his eleven decisions after the All-Star break. One, near the end of the season, came on September 24, his last decision of the year. It was a near-perfect game against Cleveland that would have been the first in over 20 years. Leading off the seventh inning, Lou Boudreau singled into short right field — the only Indian to reach base in the first nine innings. Dobson took the scoreless game through 10 innings, and the Sox won it 1-0 in the bottom of the 10th on back-to-back doubles by Tom McBride and Tony Lupien. Dobson’s final start wound up a 3-3 tie against the visiting St. Louis Browns.

Dobson was also a good defensive player. It was only in that final September 29 tie game, the last appearance in his fifth season in major-league ball, that he made the first error of his career, in his only chance of the game. The old American League record had reportedly been Ted Lyons with 88 games. Joe set the new record: 156 games and 153 chances. In 1946, Claude Passeau concluded a stretch of 275 chances without an error, in 145 games. When the “kinky-haired” Dobson had joined the Red Sox, he already had 40 chances in 75 games under his belt but he showed up in spring training with a new glove that Sox pitching coach Frank Shellenback thought was the biggest glove he’d ever seen for a pitcher, looking at first glance like a first baseman’s glove. Dobson had had it custom-designed for him, since he lacked his left thumb and part of his forefinger. The Monitor’s Rumill suggested he could distract batters a bit by waving it as he delivered the pitch.8

As a batter, Joe wasn’t much. He finished 1943 with his second sub-.100 mark, batting just .096. He’d hit one of his two career homers back in 1941 (the other came in 1948) and had only nine career RBIs after his first five years. The first home run came on June 2 during a quite uncharacteristic 3-for-4 day against Bobo Newsom and Bud Thomas; Dobson threw a four-hitter, all singles, for a 9-1 win.

As soon as the 1943 season ended, Joe took up defense work at the Bethlehem-Hingham shipyard in Hingham, Massachusetts. Christopher Williams reports that the shipyard “at its peak, when Dobson was employed there, could produce a destroyer escort ship in 25 days, 16 at a time.”9 He was inducted into the Army on December 22 in Boston, and reported to Fort Devens, Massachusetts, on January 12, 1944. He was the 17th ballplayer the Red Sox had lost to the armed services in World War II.

After early basic training, Dobson was transferred to Camp Wheeler, near Macon, Georgia, where he spent the balance of the war. He pitched in 1944 and 1945 for the Camp Wheeler Spokes, and managed the team as well. He later said, “I must have pitched at least 24 games and I lost only three. We had some good games, too. Among members of my club were Cecil Travis, former Senator; Johnny Frye, who tried out at first with St. Louis; Ken Jungels, who was up with Cleveland. We also had some double-A players in our league.” Dobson’s fellow Spokes also included Bobby Bragan of the Dodgers and Johnny Logan, not yet a major leaguer. Though most of Camp Wheeler shipped out to Europe late in 1944, Dobson was one of the more fortunate ones and remained on the base.

In June 1945, Dobson and other players at Camp Wheeler helped conduct a training camp in Macon, Georgia, for young local ballplayers. The team traveled some, playing other bases as far away as California. Cincinnati shortstop Eddie Miller wrote of a game there, “We beat Joe, but he struck out 14 and looked great.”10

Dobson twice in early 1945 took detours to Fenway Park. While traveling to Washington D.C. on detail, Sergeant Dobson parlayed a three-day pass into a visit, where he challenged Red Sox secretary Phil Troy: “Ask me some names of gun parts. I know lots of guns and I know how to pull ’em apart. I can assemble ’em, too, without havin’ any parts left, big or little.”11 Dobson was discharged on February 15, 1946, without having seen overseas duty, but just in time to join the Red Sox for spring training. He was one of the last to arrive, but the pitching during the war had kept him in good shape and he was ready to contribute a very good year to a very good Red Sox team.

Fresh out of his Army baseball uniform and into a Red Sox one again, Joe made his first start in an intrasquad game on March 5 and he set down the nine batters he faced, striking out three. For the season, Dobson started 24 games, and relieved in eight more. Just before the June 8 start in Detroit, Joe learned that his father had died in Arizona. His brother told Joe on the phone that their father would have wanted Joe to pitch, so he beat the Tigers that day — taking his record up to 7-1 — and then left for the funeral. By season’s end, Ferriss, Hughson, and Harris all had more wins but Joe had posted a very strong 13-7 record with a 3.24 ERA, doing his part to bring the team into its first World Series in 28 years, against the St. Louis Cardinals. During the Series itself, he threw one inning of hitless relief in the Game Two loss, righted the Red Sox ship with a complete-game, four-hit, 6-3 win in Game Five (all three runs unearned), and threw 2 2/3 innings of hitless relief in the middle of Game Seven. They were the only World Series games in which he appeared, and he couldn’t have acquitted himself much better.

After it was all over, Joe traveled from St. Louis back to Boston, where his wife had a thyroid operation, and then to Arizona, where he and his brother started work building a new home. It was Joe’s wife who took credit for his win in Game Five. With ongoing shortages from the war years, she said, it was the first steak she’d been able to buy in Boston all year, and she said that it helped her husband. Joe agreed it helped, but said that the real secret weapon was his “atom ball” — which he said was “the pitch I used whenever I got into trouble. It was usually a down-breaking curve that exploded like ‘Operation Crossroads.’”12 He was delayed returning home, when their car broke down in Pittsfield and it was two weeks before it was sufficiently repaired to make the journey. Steaks and auto parts still seemed hard to come by as the nation rebuilt its domestic economy.

The Red Sox looked ready to repeat in 1947, and Dobson was now seen as one of the Big Four. He’d shaken the reputation of a “dazzling spring box operative who faded in early summer.”13 As it transpired, Dobson turned out to be the only starter on the Red Sox that year who didn’t seem to come down with a dead arm. Hughson, Ferriss, and Harris all had one problem or another during the course of the season, one that failed to fulfill its promise almost from the get-go. Joe had what might have been his best year — though one could make a good case for 1952. He won a career-high 18 games as part of an 18-8, 2.95 season. By midsummer, newspapers were calling him “Cronin’s ace” and one of the few pitchers who had a shot at 20 wins that year. He had another near-no-hitter on September 17 on a blooper of a seventh-inning single to right off the broken bat of Walt Judnich; he settled for a one-hit, 4-0 shutout of the Browns.

Thanks mainly to additional struggles from its pitchers in 1948, the Red Sox were in seventh place at the end of May. A month later, Dobson had nine wins and was named to the All-Star team (he didn’t play), but on July 31 — with 13 wins under his belt — he was hit in the hand by one of Bob Feller’s pitches. He didn’t miss a start, nor did he when another Indians pitcher — Satchel Paige — hit him on August 24, but he didn’t win a game in four straight starts. When it came to the last scheduled game of the year, and the Sox needed a win over the Yankees to have a shot at the pennant, manager Joe McCarthy gave Joe the start. He kept the game close enough, and Earl Johnson and Dave Ferriss finished it. The Sox won, and found themselves in a tie with Cleveland, necessitating a single-game playoff tiebreaker that the Indians won. There would be no World Series for the Red Sox in 1948. “Curly Joe” — as John Drohan called him — had another offseason job in the Boston area, as agent for a “brewing concern.” He’d begun to make his home in Needham, Massachusetts.

All Boston needed was to win one more game to take the pennant in 1949. Joe got off to a lackluster start but he began to come around and won 14 games by year’s end. One more would have been nice. The Sox entered Yankee Stadium to play the final two games on the schedule. All Boston had to do was win either game and the pennant was theirs. Mel Parnell started the Saturday game and had a 4-0 lead, but gave up two runs in the fourth and two in the fifth. Dobson pitched four innings in relief, but lost the game on Johnny Lindell’s solo home run in the bottom of the eighth. The Sox lost the next game, too. Dobson finished 14-12, his ERA having climbed to 3.85.

Joe finally got a no-hitter late in 1949 — very late — it was a postseason exhibition game with the Mickey Harris All-Stars, and he shared the win with Warren Spahn, the two having split the duties to beat the Hartford Chiefs, 7-0.

Dobson won 15 games in 1950, the seventh of the eight seasons he was with the Red Sox that he posted double-digit win totals. He was part of a good staff led by Parnell, Ellis Kinder, and Chuck Stobbs, fronting a powerful team that set any number of records on offense, dampened only when Ted Williams broke his elbow during that summer’s All-Star Game. Dobson missed a couple of starts at the end of July, and was sent back to Boston after being hit hard in the side by a Larry Doby line drive. Joe relieved in a dozen games in addition to his 27 starts, but his ERA increased for the third year in a row, to 4.18. He finished the year 15-10, second in wins only to Parnell’s 18, and the Red Sox finished four games out of first place. Dobson was by no means opposed to working out of the pen. He told Ed Rumill he enjoyed the role and thought he could fashion a new career as a relief specialist. In 1950, he hit a career-best .214 at the plate, with nine RBIs also a career high.

On December 10, 1950, almost exactly 10 years after he’d been traded to the Red Sox, Dobson was dealt to the White Sox (with Dick Littlefield and Al Zarilla) for pitchers Bill Wight and Ray Scarborough. “I wasn’t too surprised about the trade,” he said. “When you get to be my age, you figure you have only a couple of years left.” Many thought the Red Sox had gotten a steal with Scarborough and Wight, but neither panned out as well as anticipated.

Training in Pasadena, California, provided one unexpected bonus; a photograph in the March 21, 1951, Sporting News showed Joe strolling arm in arm with Marilyn Monroe with two other White Sox on Marilyn’s other arm in the posed publicity shot. He got his first win on May 11, another one-hitter (a pinch-hit double by Bobby Avila in the eighth), against the Indians. He started well, but hit a rough stretch in June and July, getting knocked out of the box six out of ten times, and didn’t win a game between July 4 and August 6. He also missed considerable time due to what Chicago Tribune writer Ed Burns called “variegated twinges” (a number of minor but still debilitating leg problems) but still appeared in 28 games (21 starts) and put up a 7-6 record with a 3.62 ERA. It was the first time since 1946 that he hadn’t won at least 13 games.

The following year, 1952, might have been Dobson’s best season of all. He showed up early for spring training in El Centro, California, and worked hard. He lost a 1-0 game to Cleveland’s Bob Lemon in his first start, and shut out the Browns with a 5-0 three-hitter in his second. Over his first 34 2/3 innings, he gave up a total of one earned run and one unearned run — including another near no-hitter on May 1 that ran for 7 1/3 innings before any Athletics batter hit safely. He won that one as a two-hit, 3-0 shutout. The string ended with him getting pounded by the Red Sox on May 6. He won his next four, though, including his third shutout of the young season on May 25. At one point boasting a 7-2 mark, Dobson was 9-5 at midseason. The 35-year-old needed a bit of extra rest between starts as the season wore on, though, and was just 7-7 in his last 14 decisions as the White Sox finished in third place with an 81-73 record. Joe finished 14-10, with a very strong 2.51 ERA, ranking fifth in the American League. Some credited manager Paul Richards with having pushed Joe hard to get in better shape before the season got under way. Dobson was also pitching with a salary that had been cut sharply from 1951, but the cuts were restored in full before the season was over.

After the season was over, Joe took a position as the regional sales manager of a tire distributing company based in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, and did a weekly radio sportscast on Tuesday nights on WBRK.

Dobson began to transition a bit in the spring of 1953 when he helped serve as an instructor in spring training. He was considered the third man in the rotation, behind Billy Pierce and Saul Rogovin. It turned out to be a disappointing season, for both Dobson and Rogovin. Joe finished only three of his 15 starts, even though the White Sox won every one of his final four starts. Age was beginning to take its toll. He acknowledged that you reach the point where “everything you do out on the field takes effort to the limit of your endurance.” His second wife, Maxine, a nurse who never followed sports before she and Joe met in 1945, mused out loud, “I’m wondering if those close fitting baseball caps aren’t making our guys partly bald.”14 (Joe had lost his first wife Marguerite to a fatal strep infection.) Between July 11 and August 5, Joe didn’t start at all — put on the shelf. He finished the season 5-5, with a 3.67 ERA.

Finally, after picking up infielder Connie Ryan, Chicago cleared a roster spot by placing Dobson on unconditional waivers on August 29. As a 10-year man, if unclaimed, Joe would be a free agent. He shared his thoughts about finally leaving the game with his best friend among the press, Ed Rumill of Boston’s Christian Science Monitor. “When a pitcher doesn’t have as much stuff as he once had, he’s got to have sharp control to win. But if you don’t pitch often, you lose that control. That’s what happened to me. My arm is as strong as ever.” He was gracious in his remarks and didn’t blame the White Sox at all for believing that Ryan could do more to help the club. “Baseball has been very good to me,” he said.15 He said he was looking forward to spending time at home. His wife was feeling poorly, and he was tired of traveling.

The Red Sox offered Joe a last hurrah in 1954, announcing Dobson’s signing of a free agent contract on January 13. “He’s still got some good pitches in his strong right arm,” declared GM Joe Cronin. “We expect him to win some games for us and also help teach and guide some of the young pitchers we’ll have on our staff.” Manager Lou Boudreau added, “I can’t believe that Dobson is all through. He’s always taken good care of himself.” Joe didn’t really have enough left. He got into two games, long enough to record eight outs but gave up five hits and two runs and a walk — and one final strikeout, finishing his career just shy of 1,000 with 992 K’s. The Red Sox released him on May 8, offering him a coaching contract at the same time. He thought it over for a couple of days and agreed, but then resigned a little over seven weeks later, in early July. He’d worked largely as a “special observer” sitting in the stands and taking notes.

Joe decided to end his playing career — though he coached for the White Sox in 1955. By October, he was living in Munsonville, New Hampshire (population 231), and spending 12 hours a day, seven days a week operating Joe Dobson’s Store, a village general store about 10 miles north of Keene. The store also rented cabins and boats, sold gas, and Joe served as the town’s postmaster and head of the volunteer fire department. He termed it a “change of pace.” He truly enjoyed the work, living there with Maxine and an infant daughter, Pam. His 17-year-old son from his first marriage, Joe Junior, was raised elsewhere. It wasn’t easy. “Ballplayers don’t know what hard work really is,” he said. Every day you pitched extra innings, with nobody backing you up in the bullpen.16 Pam recalls baseballs and bats hanging from the store’s ceiling for a little extra decorative flavor.

By 1967, as the Red Sox embarked upon their Impossible Dream season, Joe was the manager and golf pro at the Kearsage Valley Country Club in North Sutton, New Hampshire. The year before, Ted Williams and Dom DiMaggio had earned the club some extra publicity, appearing at a benefit there. Joe had run the course at Laconia before that. He worked at Kearsage for seven years and then in February 1972 moved to Winter Haven, Florida, where he became general manager of the Red Sox complex there and business manager of the Winter Haven Red Sox through 1978.

His wife Maxine passed away in 1976. He later married Dorothy Veness, who survived his passing. After retiring from his work for the Red Sox, Joe and his family moved to his sister’s ranch outside Tombstone where he helped with ranch work, fixing fence posts and looking over a herd of 40-50 cattle. In the late 1980s, he moved to Jacksonville and truly retired. It was in Jacksonville that he died of cancer at the age of 77 on June 23, 1994.

Note

This biography originally appeared in the book Spahn, Sain, and Teddy Ballgame: Boston’s (almost) Perfect Baseball Summer of 1948, edited by Bill Nowlin and published by Rounder Books in 2008.

Notes

1. Lautier, Jack. Fenway Voices, p. 46

2. Boston Traveler, June 4, 1941

3. The Sporting News, March 20, 1941

4. Christian Science Monitor, March 4, 1941

5. Christian Science Monitor, March 4, 1942, and The Sporting News, January 15, 1942

6. Hartford Courant, March 17, 1942

7. Golenbock, Peter. Red Sox Nation, p. 135

8. The “kinky-haired” descriptor is from a 1942 Sporting News story; the glove is detailed in a March 31, 1941, Christian Science Monitor story.

9. E-mail communication from Christopher Williams, January 25, 2008

10. Christian Science Monitor, November 17, 1945

11. E-mail communication from Gary Bedingfield, January 25, 2008

12. The Sporting News, October 16, 1946

13. Stevens, Howell. The Sporting News, February 26, 1947

14. Chicago Tribune, July 28, 1953

15. Christian Science Monitor, August 28, 1953

16. Nason, Jerry. The Sporting News, October 19, 1955

Sources

Interview with Pam Dobson Garcia on February 6, 2008.

Thanks to Gary Bedingfield and Christopher Williams.

Photo Credit

The Topps Company

Full Name

Joseph Gordon Dobson

Born

January 20, 1917 at Durant, OK (USA)

Died

June 23, 1994 at Jacksonville, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.