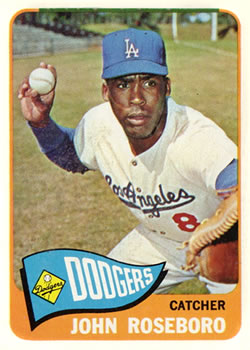

John Roseboro

“It’s too bad,” John Roseboro said, “because a ballplayer would like to be remembered for something better than a bloody brawl, but that’s what everyone always remembers.”1 What everyone remembers is August 22, 1965: the day Juan Marichal bashed Roseboro in the head with a bat.

“It’s too bad,” John Roseboro said, “because a ballplayer would like to be remembered for something better than a bloody brawl, but that’s what everyone always remembers.”1 What everyone remembers is August 22, 1965: the day Juan Marichal bashed Roseboro in the head with a bat.

He was so quiet, he was nicknamed “Gabby.” Roseboro was the invisible man behind the mask for four Los Angeles Dodgers pennant winners, a four-time all-star catcher. “With him out there,” Sandy Koufax said, “I felt like I was never alone.”2 After his playing career, he became so gabby in a tell-all book that he killed his hopes of becoming a big-league manager.

Let him tell you about himself:

The kind of guy John Roseboro was, he was a boy who took a long time to grow up, a sucker who had a great time on the field, but never could have a good time off the field, who made a lot of money on the field but blew it all off the field. … He was a boy playing a game for almost twenty years and those were the best years of his life.3

Let the great sportswriter Jim Murray tell you about him:

John was about as flamboyant as Calvin Coolidge. John was the kind of guy whose shirt and socks matched. He hardly ever spoke above a whisper. He never came to camp in a pink Cadillac. No one linked his name with any movie stars. He hated parties. Heck, he couldn’t even dance.4

He was born on May 13, 1933, in Ashland, Ohio, a small town between Cleveland and Columbus where the Roseboros were one of only a few African American families. His birth certificate reads “John Junior Roseboro,” but it probably should be John Roseboro Jr. John Sr. was a chauffeur and auto mechanic who married Cecil Geraldine Lowery when she was 15. She took in laundry and then worked at the J.C. Penney department store. John Jr. was the first of two sons; his brother Jim played halfback for Ohio State in the 1955 Rose Bowl.

The boys grew up in a small world with little obvious prejudice. John’s friends were almost all white. He remembered the solidarity of his white baseball teammates when they walked out of a restaurant that refused to serve him.

He became a catcher in high school because nobody else wanted the job. He preferred football even after he broke a leg his freshman year. He recovered to become a speedy first-string halfback and won a scholarship to Central State College in Wilberforce, Ohio.

After playing freshman football, Roseboro was ineligible for baseball because of poor grades. Brooklyn scout Hugh Alexander spotted him working out with the Central State team, liked his smooth left-handed swing and his strong 5-foot-11, 190-pound frame, and invited him for a tryout when the Dodgers were in Cincinnati. His hosts for the weekend, Roy Campanella and Don Newcombe, treated him to a room-service steak. “This is the way I want to live,” the starstruck 19-year-old thought.5 He signed for a $5,000 bonus in the spring of 1952. In later years he regretted not finishing college.6

Roseboro broke a finger on his throwing hand in his first professional season at Class-D Sheboygan, Wisconsin, and played the outfield while he was recovering. He moved up to Class C the next year as a center fielder until he was drafted into the army in mid-1953. When he returned after two years in the service, the Dodgers told him he was a catcher again. Club officials explained that they were looking for a successor to the 34-year-old Campanella.

Soon after he came home, his brother introduced him to Geraldine Fraime, an Ohio State student who became the shy young man’s first real girlfriend. “I don’t remember proposing,” he wrote later, “but maybe I did.”7 When the Dodgers promoted him to Triple-A Montreal in 1956, John and Geraldine married during the season.

Brooklyn called Roseboro up in June 1957, shortly after his 24th birthday, because the club needed an emergency first baseman to replace the injured Gil Hodges. Roseboro, who had played first only a few times in the minors, appeared in his first four big-league games at the position.

He spent the rest of the season on the bench and in the bullpen as the third-string catcher, but it wasn’t wasted time. Campanella became his roommate and “like a father,” teaching the young man how to act like a big leaguer and taking him and Jeri out on his boat.8 Campy and his backup, Rube Walker, schooled him on “catching philosophy rather than mechanics,” Roseboro said. “I learned how to set hitters up, what they looked for in certain spots. It became like a chess game then, and very exciting to me.”9 He got into only 19 games behind the plate while hitting just .145.

When Campanella’s devastating car wreck in the winter ended his career and left him in a wheelchair, it also changed Roseboro’s life. Dodgers executives, gripped by the upheaval of their move to Los Angeles, didn’t acquire a new catcher. Instead they went with what they had in 1958: the green Roseboro, Rube Walker, who had never been much of a hitter in seven years as Campy’s caddy, and Joe Pignatano, who had played in all of eight big-league games.

Walker started on Opening Day at San Francisco in the first major-league game in California. Roseboro replaced him as a pinch-runner in the seventh and finished up. He got the start in the second road game and in the home opener two days later. Before more than 78,000 fans in the vast Los Angeles Coliseum, his shaky nerves were on display. “He shot that ball back to me and almost hit me in the face,” starting pitcher Carl Erskine remembered. “I said, ‘John, the catcher is not supposed to throw harder than the pitcher.’”10

Within a month, Roseboro won the everyday job, and Walker soon retired to join the coaching staff. The 25-year-old had been a full-time catcher for only two years in the minors and had caught just 138 big-league innings before that season. “I was thrown in and it was sink or swim,” he said.11

“I don’t know how good he’s going to be,” manager Walter Alston observed, “but he has all the raw tools to be great: an arm, speed and power. There are a lot of things about catching that he doesn’t know yet, but if we can afford to go along with him until he does learn, I think he’s going to pay off big for us.”12

Roseboro’s inexperience showed. He was charged with eight errors, mostly on wild throws. The rest of the Dodger catchers only committed one miscue. He caught only 37% of base stealers while the others nailed 65%. When Dodgers pitchers posted the worst ERA in the league and the team sank toward the bottom of the standings, a narrative developed that the pitchers missed Campanella and didn’t trust the new kid. The Coliseum’s ridiculous 251-foot left-field fence doubtless was more responsible for the staff’s failures.

Still, Roseboro made the 1958 All-Star team as a reserve and kept his batting average close to .300 for much of the season. He wound up at .271 with a .788 OPS and 14 homers. The Dodgers finished seventh in the eight-team league, their worst showing since World War II. The Boys of Summer, seven-time pennant winners in Brooklyn, had gotten old. Roseboro was part of the new generation that would create new memories and new triumphs in their new home.

The turnaround began in mid-1959 when General Manager Buzzie Bavasi called up pitchers Roger Craig and Larry Sherry and shortstop Maury Wills. They led a September charge. A three-game sweep of the first-place Giants put the Dodgers on top with a week to go, but the Milwaukee Braves caught them on the final weekend to force a playoff, best two out of three.

In the first playoff game, Roseboro’s sixth-inning homer provided the winning run in the Dodgers’ 3-2 victory. The next day they won another one-run decision, this time in 12 innings, to take the pennant.

Roseboro was the talk of the World Series: Could he stop the Go-Go White Sox, the majors’ leading base stealers? Chicago didn’t test him until Game Three. Jim Landis stole second in the first inning, but Roseboro threw out Jim Rivera in the second. Then he cut down the majors’ No. 1 thief, Luis Aparicio, in the fourth and caught Nellie Fox in the fifth. The Go-Go Sox dared to go only once more in the final three games. They apparently hadn’t known, and had to find out for themselves, that Roseboro had thrown out 60 percent of runners during the regular season.

He got a share of the credit when the Dodgers won the championship in six games, but reliever Larry Sherry was the star, winning two games and saving the two other victories. For Roseboro, the biggest event of 1959 was the birth of his first child, Shelley. He and Jeri later had a second daughter, Stacy, and adopted son Jaime.

For the next two years, the Dodgers continued to get younger, filling the lineup with farm-system products Tommy and Willie Davis, Frank Howard, and Ron Fairly. In 1962 the club moved into its permanent home, Dodger Stadium in Chavez Ravine. It played as one of the most extreme pitcher’s parks in the majors, so Bavasi and manager Alston built their roster around pitching, defense, and speed. “Wills was our offense, Koufax our defense,” Roseboro wrote.13

Koufax had help. Don Drysdale won the Cy Young Award as the majors’ best pitcher in 1962; then Koufax won in 1963, ’65, and ’66. Roseboro recalled that even with his explosive velocity, Koufax threw a very light ball while Drysdale’s right-handed fastball “felt like a big rock” that bruised his hand through the mitt.14

“Drysdale was a good pitcher, but he had to work hard to win,” Roseboro said. “So we had to work hard when Drysdale pitched. Koufax made it easy. He took the pressure off. If the other team got two hits, man, they were lucky.”15 Roseboro marveled at Koufax’s otherworldly talent: “I think God came down and tapped him on the shoulder and said ‘boy, I’m gonna make you a pitcher.’ God only made one of him.”16

After tying for first place in 1962, and losing to the Giants in a playoff, Los Angeles took home World Series titles in 1963 and ’65, then were swept out of the 1966 Series by the Baltimore Orioles.

The Dodgers were nervous about returning to New York for the ’63 Series; Brooklyn had lost six of its seven matchups with the Yankees. Roseboro and his roommate, Wills, calmed themselves with sips of peach brandy before Game One. In his first at-bat, Roseboro powered a three-run homer off Whitey Ford’s hanging curveball. Koufax struck out a Series record 15 batters to start the Dodgers on their way to a four-game sweep.

Roseboro’s batting stats fell off sharply in the 1960s along with most everybody else’s as baseball entered its second deadball era with an expanded strike zone. Bavasi once called him “the best .240 hitter in the history of the game.”17 In the low-scoring environment, and playing half his games at the pitcher’s paradise, Dodger Stadium, he was about a league-average hitter. In 1964 he switched to a heavier Drysdale-model bat and posted a career-best .287 batting average. But he was playing in pain from a knee injury that had to be drained several times. At 31, he had suffered the usual dings and dents that were the inevitable lot of the man behind the plate.

A leadership role also comes with the catcher’s job. “Roseboro was the conscience of our club,” said Dick Tracewski, utility infielder and longtime big-league coach. “He was a steadying influence. He was a bright guy who knew the game and how to handle pitchers. He was fair to everyone. He was a quiet leader. If he had something to say, you listened. And like Maury, he would do anything to win.”18

But even in the 1960s, African Americans still weren’t welcome in some hotel restaurants. Roseboro ate most meals in his room. At the Chase Hotel in St. Louis, one of last to integrate, he especially savored the kitchen’s creamed chicken omelet, but always ordered it from room service. Wills couldn’t persuade him to come down to the restaurant. Pointing to the new Civil Rights Act of 1964, outlawing segregation in public accommodations, Wills argued, “When you get some freedom, you need to use it.” He thought the burden of segregation had worn his roomie down.19

The Dodgers and archrival Giants were locked in another tight pennant race in August 1965. The Giants held a 1½ game lead, and the series had generated more trash-talk than usual when the teams’ aces, Koufax and Marichal, squared off at San Francisco’s Candlestick Park on August 22. Wills led off with a bunt single and came around to score. When he came up again in the second, Marichal knocked him down.

Under the game’s unwritten rules, that called for retaliation, but Koufax was notoriously unwilling to throw at a batter. He retaliated, sort of, by slinging a pitch far above Willie Mays’s head. In the next inning, Marichal low-bridged Ron Fairly.20

“I’ll take care of it,” Roseboro told teammates. When Marichal came to bat, Roseboro, throwing the ball back to Koufax, buzzed it within inches of Marichal’s face. Marichal insisted it clipped his ear. They barked at each other. Marichal said Roseboro made a crude remark about his mother. Roseboro began to rise up out of his crouch, and Marichal swung his bat and hit him in the side of the head — three times, Roseboro said.

“I’ll take care of it,” Roseboro told teammates. When Marichal came to bat, Roseboro, throwing the ball back to Koufax, buzzed it within inches of Marichal’s face. Marichal insisted it clipped his ear. They barked at each other. Marichal said Roseboro made a crude remark about his mother. Roseboro began to rise up out of his crouch, and Marichal swung his bat and hit him in the side of the head — three times, Roseboro said.

With their catcher bleeding, angry Dodgers charged toward the plate. The Giants’ on-deck hitter, Tito Fuentes, advanced with his bat raised. All hell broke loose. This was no ritual shoving match. Several Dodgers had murder on their minds. Left fielder Lou Johnson, intent on maiming Marichal, found himself lifted up and carried away in a bear hug by the giant Giant Willie McCovey.

Roseboro tried to get at Marichal, but Mays pulled him back, shielded him, and guided him into the Giants’ dugout with a towel pressed to his bloody head. The game’s greatest player was weeping; he thought Roseboro’s left eye had been gouged out because he could see only blood.

The Battle of Candlestick raged for 14 minutes before play resumed. Roseboro had a two-inch gash in his head; he declined stitches and was back in the lineup three days later.

National League President Warren Giles fined Marichal $1,750 and suspended him for eight playing days. The Dodgers weren’t the only ones who thought that was less than a tap on the wrist. He missed only one start, and a second one was delayed a couple of days. Marichal always maintained that he was defending himself because he thought Roseboro was about to hit him with his mask.

A photo of the attack was published widely, making Roseboro famous and Marichal infamous. Roseboro sued the pitcher for $110,000. When they settled the case seven years later, he said he received about $7,000.

The Dodgers’ glory days ended temporarily after the young underdog Orioles swept them in the 1966 World Series. Koufax suddenly retired at 30 because of elbow arthritis, and Wills and Tommy Davis were traded. Roseboro’s Dodger days ended after the 1967 season when he was swapped to the Minnesota Twins as part of the price for shortstop Zoilo Versalles, who the Dodgers hoped could replace Wills. (A misplaced hope.) Roseboro was 34, past the sell-by date for a regular catcher, and the Dodgers were seldom sentimental about getting rid of aging players.

Buzzie Bavasi did give him a going-away present. Roseboro said Bavasi signed him with a pay raise to $60,000 before the trade. But his rich salary pained the tender checkbook of his new employer, Twins owner Calvin Griffith, “the least likeable person I met in baseball.”21 After Roseboro hit just .216 in 1968 (the year of the pitcher), Griffith slashed his salary to $48,000. Even after the Twins won the Western Division the following year, and Roseboro made the All-Star team, Griffith refused to restore the cut. Instead he released the 36-year-old.

Roseboro hooked on with the Washington Senators under manager Ted Williams. Before the end of the 1970 season he was released and made a coach. He served as bullpen coach for the California Angels from 1972 through 1974, applied for the manager’s job, but was turned down. The new manager, Dick Williams, let him go.

A coach’s salary of $18,000 was quite a comedown. His wife, Jeri, couldn’t handle the loss of income and status. John’s unemployment made it worse. He left his family and claimed Jeri turned their three children against him.

During his playing career, Roseboro had begun scouting for business opportunities. “I had a philosophy that if you tried four or five you only needed one to succeed in order to survive outside of baseball when you were done. That philosophy didn’t work out too well.”22 As a ballplayer with a little money and no business savvy, he was an easy mark for hustlers who roped him into their deals: real estate, a travel agency, a gas station, a record company, and that athletes’ standard, a glitzy nightclub. Every one was a failure that left him in debt, unable to meet his child-support obligations. At one point, bankrupt and cut off from his children, he determined to solve his problems with a gun, but couldn’t decide between robbery and suicide.

“I think I’d have blown my brains out if it hadn’t been for Barbara,” he said.23 Barbara Walker Fouch was a long-distance friend he had met in Atlanta, a former model who ran her own public-relations firm. Since she was also going through a divorce, they cried on each other’s shoulders in long phone calls.

Barbara gathered up her daughter Nikki and moved to Los Angeles, where she opened a new PR agency and took in John as a partner. With her professionalism and charm, she developed connections in the film industry and politics. They soon married.

Roseboro still yearned to get back into baseball. In 1978 the Dodgers gave him a low-level job as a minor-league hitting and catching instructor. At least it was a foot in the door.

Then he shot himself in the foot. His autobiography, Glory Days with the Dodgers and Other Days with Others, became a minor sensation. He pulled no punches in the book about his own failings or those of his teammates, even angering his friend Maury Wills. He also aired his grievances against the baseball establishment.

He wrote it because he needed money. When he was down and out, he said, “Nobody’s helped me. …Maybe two or three people were concerned and tried to help. So I thought screw it. I don’t care whether people like me or dislike me.”24

One reader was Walter O’Malley. A reporter spied the book on the Dodger owner’s desk. “It’s terrible,” he said. He was “very upset.”25 Roseboro’s contract as an instructor was not renewed.

The book probably ended Roseboro’s chance of managing in the majors, if he ever had one. No more coaching jobs, either. “The game is layered with cronyism. All these white guys just keep hiring their pals as coaches. That’s why I don’t call what’s going on racial prejudice. I have many close white friends in baseball and I never met a racist yet. But this is just a closed system and no one I know can do anything about it.” He refused to seek a minor-league job. “I have a Ph.D. in baseball, but I can’t use it,” he concluded.26

At a Dodgers old-timers day, Roseboro had crossed paths with Juan Marichal, who had finished his career with LA, and the two made peace more than a decade after the Battle of Candlestick. When Marichal became eligible for the Hall of Fame, with the class of 1981, he received only 58 percent of the votes, nowhere near the 75 percent needed for election. To twist the knife, his rival Bob Gibson, also a first-timer, was elected easily. The two pitchers’ lifetime statistics were nearly identical.

Marichal thought some sportswriters had refused to vote for him because of his attack on Roseboro. “If that had something to do with the voting, I would like to ask all the writers who didn’t vote for me if they have ever done any wrong thing in their life,” he said. Roseboro said he deserved to be elected. So did Gibson, who added, “I wasn’t a better pitcher than Marichal.”27

The next year Marichal’s support jumped to 73.5 percent, still 7 votes short. Roseboro’s wife said a discouraged Marichal called John and asked for his help. A few months later Roseboro publicly hugged him when they were introduced before another old-timers game at Dodger Stadium. And he flew to the Dominican Republic to play in Marichal’s charity golf tournament. On his third time on the ballot, Marichal got over the hump and was inducted in 1983. He called Roseboro again, crying, according to Barbara Fouch-Roseboro: “all he could say was ‘thank you, thank you, thank you.’”28

John and Barbara worked together in their business while he found occasional jobs in baseball, though only on the fringes. After Walter O’Malley’s death, his son Peter rehired Roseboro as a catching instructor. Major League Baseball appointed him to a part-time post as an umpire evaluator.

But his health began to fail when he was still in his fifties. Several strokes, prostate cancer, and heart disease led to 51 emergency room visits over 14 years. He was near death in the summer of 2002, but rallied after phone calls and messages from many baseball friends, including Marichal. “It was everybody he had once stood up for, standing up for him,” Barbara said. She believed the outpouring of love helped keep him alive for two more months before another stroke killed him on August 16, 2002, at 69.29

“After my husband passed away, Juan would call to check up on me and our daughter every six months or so,” Barbara said later.30

Back in 1965 a 10-year-old boy had seen Marichal’s attack on TV. “It was particularly traumatic for me to witness that kind of violence,” Roger Guenveur Smith recalled, “because John Roseboro was someone that I had known not only as a Dodger, but had also met at a community event, where he had given me an autograph.” That day young Roger destroyed his Juan Marichal baseball card. Four decades later he wrote and performed a one-man play about the incident.31

Juan and John was staged in New York in 2009 and Los Angeles in 2011, where Barbara was in the audience. In the play Smith repeated what Juan had said at John’s funeral: One of the greatest things that ever happened in his life “was John Roseboro forgiving me.”32

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Jan Finkel and fact-checked by Jeff Findley and Chris Rainey.

Notes

1 John Roseboro with Bill Libby, Glory Days with the Dodgers (New York: Atheneum, 1978), 3.

2 Bill Plaschke, “Home Base,” Los Angeles Times, June 30, 2002: D4.

3 Roseboro, 127-128.

4 Jim Murray, “The Book on Roseboro,” Los Angeles Times, May 24, 1978: III-1.

5 Roseboro, 52.

6 Player questionnaire in Roseboro’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame library, Cooperstown, New York.

7 Roseboro, 80.

8 Roseboro, 107.

9 Steve Calhoun, “Where are they now: John Roseboro,” June 15, 1983, clip in Roseboro’s HOF file.

10 Steve Dilbeck, “Roseboro’s Skills Overlooked,” Los Angeles Daily News, August 20, 2002, online edition.

11 Roseboro, 183.

12 Paul Zimmerman, “Sportscripts,” Los Angeles Times, May 26, 1958: IV-1.

13 Roseboro, 212.

14 Roseboro, 185.

15 Steve Delsohn, True Blue (New York: HarperCollins, 2001), 75.

16 Jane Leavy, Koufax: A Lefty’s Legacy (New York: HarperCollins 2002), 2.

17 Murray, “The Book.”

18 Delsohn, 169.

19 Michael Leahy, The Last Innocents (New York: Harper, 2016), 232-233.

20 The account of the brawl is drawn from these sources: Roseboro, Glory Days; Leahy, The Last Innocents; Curley Grieve, “A Bat-Swinging Brawl,” San Francisco Examiner, August 23, 1965: 1; Bob Hunter, “Candlestick Brawl Brewed Two Days,” Los Angeles Herald-Examiner, August 23, 1965: C1; Mike Mandel, SF Giants, An Oral History (Privately published, 1974).

21 Rich Roberts, “John Roseboro Tells the Truth,” Los Angeles Times, July 21, 1978: III-10.

22 “What Ever Happened to … John Roseboro,” Ebony, January 1979: 68.

23 Roseboro, 288.

24 Rich Roberts, “John Roseboro Tells the Truth,” Los Angeles Times, July 21, 1978: III-10.

25 Penelope McMillan, “L.A. Ravine Still Fertile Soil for O’Malley,” Los Angeles Times, June 4, 1978: 24.

26 Brian Burwell, “The only breaks for blacks are broken promises,” New York Daily News, April 19, 1987: C44.

27 United Press International, “Marichal hopes Roseboro tiff didn’t cut his vote,” San Francisco Examiner, January 16, 1981: F2; “Gibson only one to make Hall of Fame,” Examiner, January 16, 1981: F5.

28 Plaschke, “Home Base.”

29 Plaschke, “Home Base.”

30 Gwen Knapp, “40 years later, the fight resonates in a positive way,” San Francisco Chronicle, August 21, 2005. Barbara Fouch-Roseboro died in 2012.

31 Kathryn Walat, “The Personal Historical: Roger Guenveur Smith,” Brooklyn Rail, December 2009. https://brooklynrail.org/2009/12/theater/the-personal-historical-roger-guenveur-smith-dec-09, accessed September 14, 2019.

32 Bruce Weber, “A Fan Weaves a Tale of Fighting and Forgiveness,” New York Times, December 7, 2011.

Full Name

John Junior Roseboro

Born

May 13, 1933 at Ashland, OH (USA)

Died

August 16, 2002 at Los Angeles, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.