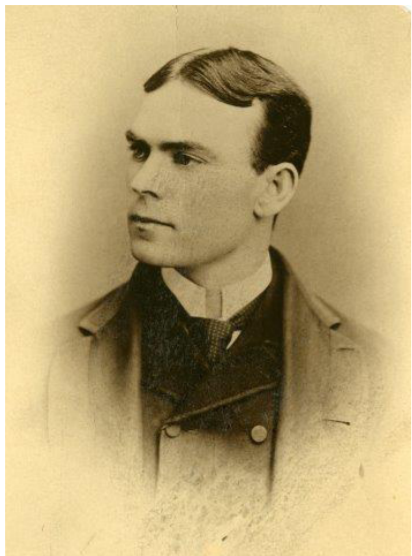

Larry Corcoran

“Flint and Corcoran had funny signals for changes of curves,” recalled Tommy Burns, a teammate of catcher Frank “Silver” Flint and pitcher Larry Corcoran of the Chicago White Stockings of the 1880s. “(Corcoran) invariably carried a mammoth chew of tobacco in his mouth, and when he chewed he shifted it about with a movement that resembled the actions of an elephant begging peanuts of a crowd of children. Flint noticed this peculiarity and one day suggested to Larry that he make his curve signals by shifting the chew. It worked to a charm, and many an old-timer was fooled.”1

“Flint and Corcoran had funny signals for changes of curves,” recalled Tommy Burns, a teammate of catcher Frank “Silver” Flint and pitcher Larry Corcoran of the Chicago White Stockings of the 1880s. “(Corcoran) invariably carried a mammoth chew of tobacco in his mouth, and when he chewed he shifted it about with a movement that resembled the actions of an elephant begging peanuts of a crowd of children. Flint noticed this peculiarity and one day suggested to Larry that he make his curve signals by shifting the chew. It worked to a charm, and many an old-timer was fooled.”1

Larry Corcoran was a dominant pitcher in the early 1880s despite a less-than-intimidating 5-foot-3, 127-pound frame that gave him the nickname “Little Corcoran.” One of baseball’s early curveball masters, Corcoran was a part of three pennant-winning Chicago teams. He was a true workhorse, averaging 456 innings pitched and 34 wins per season for five years, until his arm, understandably, burned out. Unable to adjust to life outside of baseball, he turned to alcohol and died at the age of 32.

Lawrence J. “Larry” Corcoran was born on August 10, 1859 in Brooklyn, New York, to William and Ann (Boylan) Corcoran, Irish immigrants. According to the 1860 US Census, William worked as a butcher. Lawrence was listed as a 19-year-old “ballplayer.” He had six siblings: older brothers William and Michael, younger sisters Frances, Margaret, and Mary, and a younger brother, Thomas.

In 1897 Bennett Wilson recalled the 1870s when he pitched on a Brooklyn Lurlines amateur team that included Corcoran and fellow future major-league pitchers Terry Larkin and Mickey Welch. They would gather “in a big back yard almost every day and used a clothes line horse, which was used by an old widow on which to dry her washing, with which to gain control of the various curves. The horizontal bar across the horse was supposed to represent the height of a batter’s waist and the ball was curved around the main sticks. This afforded an effective means of practice.”2

Corcoran pitched in the spring of 1877 for two Brooklyn teams, Chelsea and the Mutuals. On May 19 the New York Clipper, in an article on a Chelsea game, mentioned “that fine young player and pitcher Corcoran.”3 The Brooklyn Eagle earlier reported that the Mutuals had “an excellent pitcher in Corcoran — a player well worthy a position in a strong professional nine.”4 The Mutuals played on the Capitoline Grounds. In June Corcoran moved on to play for the Livingston Club of Genesco, New York. While there was no pitching line for the game, the June 30, 1877, Clipper noted that “Corcoran, their new pitcher, made his first appearance with them in this game, and played well.”5

Corcoran joined the Springfield (Massachusetts) club in 1878. “He is a swift, effective pitcher, one of the best curves in the business, a sure infielder and excels in watching the bases. His only fault is too great an anxiety not to give his opponents a hit, which causes him to pitch wildly and to put too much work upon himself and the catcher” wrote the Springfield Republican.6 In August Corcoran moved to the Buffalo Bisons, at the time an independent “minor-league” team.7 He returned to Springfield in 1879 because no catcher in Buffalo could be fund who could handle his pitching.8 Corcoran may have thrown a no-hitter on May 14, 1879; the Springfield Republican reported, “Not a base hit was made from Corcoran’s pitching,” although it is not known if he pitched the entire game.9 The Springfield Club disbanded on September 6, 1879, and Corcoran was briefly with the Holyoke (Massachusetts) club, before being released on the 23rd.10 He joined the Worcester (Massachusetts) club for just a few days and was asked to join the major-league Chicago White Stockings on a trip to California in October.11 Chicago pitcher Terry Larkin had a sore arm, giving Corcoran a chance in the major leagues.12

“He was a very little fellow,” Chicago manager Cap Anson recalled of Corcoran in his memoirs, published in 1900, “with an unusual amount of speed, and the endurance of an Indian pony. As a batter he was only fair, but as a fielder in his position he was remarkable, being as quick as a cat and as plucky as they made them.”13 Despite his height, Corcoran was a tough scrapper. “I remember a set-to that he had one night in the old clubhouse with Hugh Nichols, in which he all but knocked Hughy out, greatly to that gentleman’s surprise, as he had fancied up to that time that he was Corcoran’s master in the art of self-defense,” Anson recalled.14

As the White Stockings gathered for the start of the 1880 season, the Chicago Tribune mentioned that their new pitcher, Corcoran, “has developed into a left-handed pitcher, and it is expected that his double method of delivery will prove extremely puzzling to batsmen.”15

Corcoran won his first major-league start, on Opening Day, May 1, in Cincinnati, a game called “one of the most exciting ever seen here.”16 Chicago rallied in the ninth inning for a 4-3 win. Corcoran pitched the first five games of the season, and Fred Goldsmith pitched the next four games. Beginning on May 18, manager Cap Anson alternated the two pitchers in 15 of the next 16 starts, the very first formation of a pitching rotation in professional baseball. The two pitchers started 84 of 86 games, Corcoran throwing 536⅓ innings and Goldsmith 210⅓. Anson liked the contrast between Corcoran, a hard-throwing pitcher, and Fred Goldsmith, a “slow-baller.”17

The Tribune called the White Stockings-Providence Grays game on June 4 “the most extraordinary game of ball ever played.” Corcoran and John Montgomery Ward of Providence pitched all 16 innings before the game was ended by darkness with the teams tied, 1-1.18 On August 5 Corcoran threw a two-hitter against Boston, outdueling Tommy Bond.19 On August 10 he pitched a one-hitter against Providence. The Tribune said, “(T)he heavy hitters of the visiting team were completely baffled by Corcoran’s slow and swift curves.”20 The win put Chicago in first place by 12½ games over the Grays.

On August 19, in the days before the phrase “no-hitter” was used, Corcoran defeated the Boston Red Stockings who, as the Tribune put it, “obtained neither a tally nor a base-hit,” adding, “Corcoran was never in such form before, and Flint caught him superbly.” A rain delay in the third inning made the ball “mushy and shapeless for the greater part of the play,” but Chicago, the Tribune added, had 13 hits.21 Corcoran finished the season 43-14 with a 1.95 ERA. His 268 strikeouts, 4.5 strikeouts per nine innings, and 99 walks (the fewest) led the league. Goldsmith was 21-3 with a 1.75 ERA, and Chicago easily won the pennant.

Corcoran and Goldsmith again formed a two-man starting rotation in 1881. Corcoran shut out Cleveland on May 3, allowing only three hits, and pitched a three-hitter against Providence on June 24.22 On August 4 he pitched a two-hitter against Buffalo in what the Tribune called “perhaps the best game of all his life,” adding, “His headwork and his consummate control of the ball he never abated for an instant.”23 Corcoran pitched a four-hit, 5-1 victory over Buffalo on August 17. Corcoran and Goldsmith were said to be trying a “snake ball” as their curves were dominating the league.24 On August 23 Goldsmith sprained an ankle in the third inning, so Corcoran came “in from the turnstile” and pitched the rest of the game with Chicago defeating Detroit in the 12th inning.25 The White Stockings easily won the pennant again, and Corcoran was 31-14 with a 2.31 ERA in 396⅔ innings pitched. His 31 victories tied Boston’s Jim “Grasshopper” Whitney for the league lead, but Whitney lost 33 games.

Chicago struggled in the early part of the 1882 season, falling to 12-14 and fifth place on June 15. Corcoran hit a grand slam on June 20 against Worcester, “a tremendous drive to the seats in centre field,” according to the Tribune, and driving in seven of the 13 runs Chicago scored.26 Then the White Stockings got hot, going 21-6, and at the end of July were 33-20. Chicago scored six or more runs in 23 of Corcoran’s 40 starts.27 Corcoran won 10 consecutive starts from June 29 to July 29, including wins of 23-4, 35-4, and 17-1.

Chicago went on an Eastern road trip from July 27 to August 24 and didn’t return home until August 29. By the time the White Stockings returned home, Corcoran was a married man. The exact date is unknown, but two user-created family trees on Ancestry.com list August 20 or August 25, 1882, with no official documentation given. After a 15-4 pounding of the White Stockings by Worcester on August 23, the Cincinnati Enquirer wrote, “Corcoran was off being married … and Goldsmith is Chicago’s only pitcher.”28 The Boston Herald on August 29 wrote that Corcoran was “enjoying his honeymoon, having been recently married.”29 His bride was Gertrude Grork of Newark, New Jersey.30

At the end of August, Chicago trailed first-place Providence by 2½ games, and then went on a 16-2 streak. Corcoran again won 10 straight starts, including his second no-hitter, against Worcester on August 20. The day was “raw and disagreeable” with 1,500 spectators, wrote the Tribune, and “play began at 3:30 sharp in order to enable the Worcesters to take an early train for the East.” The 90-minute, 5-0 win showed that Corcoran “has been pitching a great game of late — perhaps the best of his life.”31 Corcoran finished the season 27-12 with a league-best 1.95 ERA in 355⅔ innings pitched, and Chicago won its third straight pennant, by three games over Providence.

On May 22, 1883, a freezing cold day, Corcoran defeated Boston 4-3 to put the White Stockings a half-game ahead of Providence in first place. The game featured the debut of Chicago left fielder Billy Sunday, who struck out in all four at-bats.32 Chicago swooned in June, tumbling out of first place on June 11 and falling seven games behind on the 23rd. Corcoran threw shutouts on June 9, July 18 (a one-hitter versus Boston), and August 29.33

Chicago won 11 in a row from August 22 to September 8, including 10 straight home victories, and moved into first place 1½ games over Boston.34 Then the White Stockings traveled to Boston for a four-game series. They dropped the first game. The next day Corcoran pitched hitless ball through four innings in a duel with Jim Whitney. Two runs in the ninth inning gave the Beaneaters the 3-2 win and sole possession of first place, a lead they did not relinquish as they won the pennant.35 Corcoran finished 34-20 with a 2.49 ERA in 473⅔ innings pitched. This was the first year in which he did not league the league in wins, ERA, or strikeouts.

American Sports (reprinted in the Chicago Tribune) reported on a debate between Corcoran and Anson over “place-hitting.” “Anson took the ground that he could hit a ball in any direction he chose. Corcoran held the contrary, and offered to bet a dollar on every ball hit that Anson couldn’t do it.” Anson attempted to prove it in that afternoon’s game, but went hitless in six at-bats, with only half of his batted balls going in the intended direction.36

For 1884 the White Stockings offered Corcoran a contract for $2,100, a raise of $300 from 1883. He wanted $4,000. This was “an outrageous demand,” wrote Chicago’s Inter Ocean on December 9. Corcoran demanded his release, but was refused, so he threatened to sit out the 1884 season. Go ahead and sit out, the club said. Corcoran reconsidered and accepted the $2,100. “The National League is to be congratulated on the wisdom displayed in the adoption of this reserve rule,” the Inter Ocean commented, “for without it the position of pitcher or catcher would soon command a higher salary than the President of the United States receives.”37

But Corcoran wrote to team president Albert Spalding that he was withdrawing his request and had signed with the Chicago team in the new Union Association. The National League expelled Corcoran.38 The New York Clipper published a letter from Corcoran explaining his actions. He wrote, “I asked the large salary not because I thought I would get it, but in hopes of inducing the management to give me my release. After a short consideration Mr. Spalding informed me he would pay me no such exorbitant salary, and, as we could not come to satisfactory terms, I started for my home without signing.” Corcoran entertained an offer from the Chicago Unions president, Albert H. Henderson. Then he saw a story in a Boston paper claiming he was in a conspiracy with fellow White Stockings Flint and George Gore to grab higher salaries from management, which Corcoran denied. The story said Chicago would do just fine without Corcoran, prompting him to sign with Henderson. “For four years I have fulfilled my contracts to the letter and have worked hard and faithfully for the Chicago Club, but as my contracts never spoke of a reserve-rule or made any mention of one, I do not feel I am breaking my word in any way to that club. … Leaving the public to judge my action, I am, respectfully, Lawrence J. Corcoran.”39 Henderson’s contract to Corcoran was said to be $3,000.

But Spalding threatened to blacklist Corcoran if he failed to sign by January 6, 1884, so on January 4 Corcoran re-signed with the White Stockings for $2,100.40 Apparently Corcoran wasn’t too perturbed at the new contract because six days later he was pitching in a baseball game played on ice skates in Brooklyn. The team captains were Henry Chadwick and George Taylor, and players were both amateur and professional. It was played at the Washington Skating Park in South Brooklyn and “the diamond was laid out on the Fourth-avenue and Third-street corner, there being a clear space for the regular skaters in front of the grand-stand.” Corcoran’s team won 41-12.41

The White Stockings had a forgettable 1884 season. They were 5-14 on May 26. Injuries contributed to the slow start. “A nine composed about one-third of ‘has-been’ material will not win the championship this year,” whined the Tribune.42 Chicago never spent a day in first place, finishing 62-50 in fourth-place, 21½ games behind. Corcoran won only two of his first 12 starts before pitching a one-hitter on May 23.

On June 16, with Goldsmith in Canada, Corcoran, suffering a sore pitching hand, alternated his left and right hands in a desperate attempt to pitch a game in Buffalo. The Buffalo Commercial Advertiser said Corcoran had a “felon” on his right index finger and had “no business in the box. Why in the name of common sense Anson permitted Goldsmith to go to Canada and persisted in playing Corcoran, when the little man was suffering excruciating pain, is a question no one can answer. It was an act at once brutal and stupid. Larry used his right and left hands alternately, but it was no go.”43 He was removed after four innings.

Corcoran came back to throw a no-hitter against Providence on June 27. “The fact that Chicago has at least one pitcher was demonstrated very plainly in yesterday’s game,” wrote the Tribune, “in which the Providence team, composed of the heaviest batters in the league, failed to earn a single base in nine innings.”44 It was Corcoran’s third no-hitter and a 6-0 victory. Corcoran was the first pitcher to throw three no-hitters.45 Corcoran also pitched shutouts on July 1 and 7.

“The Chicagos, thinking they could win with any pitcher, presented a brother of Larry Corcoran’s and the home team made him think he had better sign with amateurs,” wrote the Inter Ocean on July 16 after the White Stockings lost to Detroit, 14-0, the day before.46 Corcoran’s older brother, Mike, made his debut against Detroit and pitched a complete game giving up 16 hits, seven walks, five wild pitches, and 14 earned runs. It was Mike Corcoran’s only major-league appearance.

Larry Corcoran finished the 1884 season 35-23 with a 2.40 ERA, his fifth straight year of 27-plus wins, and the fourth year out of five in which he won over 30 games. He pitched 516⅔ innings, his most since 1880, as Goldsmith pitched only 188 innings and was released on August 7. Both pitchers, not surprisingly, suffered from tired arms. Goldsmith had pitched 1,516⅔ innings in five years for Chicago, Corcoran 2,279. Goldsmith was 107-63, Corcoran 170-83, but the days of the first pitching rotation were over. Newcomer John Clarkson, who was 10-3 with a 2.14 ERA in 14 games, “already ranks as one of the foremost of league pitchers, and Corcoran will have to look to his laurels next season,” wrote the Tribune.47

Corcoran pitched his last shutout on May 14, 1885, at Philadelphia, one of the last highlights of his career. Anson began using Clarkson as the predominant starting pitcher, abandoning any sort of rotation. Corcoran’s last Chicago start was an 11-10 win at Boston on May 26, in which he surrendered 15 hits and in the sixth inning “handed the ball to [Fred] Pfeffer and refused to be hammered any longer.”48 Corcoran was nursing a sore arm and was “impatient to get into his uniform, and says he is quite confident of being able to take the field within a few days’ time,” reported the Tribune on June 22.49 But he was only 5-2 with a 3.64 ERA in 59⅓ innings, and was released on July 11, “ordered to keep his arm in a sling for two months,” wrote the Inter Ocean, adding, “He will leave for his home in Newark, N.J., this evening, and will be seen no more upon the ball field for a time.”50 Corcoran complained that Chicago had not paid him for the 41 days he had been out injured. Spalding replied, “I paid him $750 for the seven games in which he played. … I bought him his railroad ticket from Chicago to New York … and I loaned him $100 on my personal account, and he was profuse with his thanks.”51

Corcoran quickly signed with the New York Giants. “It is insinuated that Corcoran’s arm is as good as it ever was, and that the ‘sore arm’ business was simply an excuse to get his release,” the Inter Ocean complained.52 “This is a wise move,” the New York Times commented. “In condition Corcoran is a first-class pitcher.”53 New York was in second place, trailing first-place Chicago by 2½ games. Corcoran started three games at the end of the season, pitching well, going 2-1 with a 2.88 ERA. He got his last major-league win on October 8 at St. Louis. He left the game in the eighth inning with to a sprained ankle.54

Corcoran never again pitched for New York, and played in only one game as an outfielder for the Giants in 1886. He was “loaned” to the Washington Nationals for $2,200 “to use him while the New-Yorks could get along without his services.”

“I feel in good condition. … I think I will get a good chance to show that I can curve a ball with as much skill as I did when I was a member of the Chicago Club,” Corcoran told the Times.55 Corcoran played shortstop for nine games and the outfield for 11 games, batting .185. He pitched in two games for the Nationals in 1886, losing 10-4 in Kansas City on July 6. “Corcoran pitched for Washington,” the Washington Daily Critic wrote, “and demonstrated that his best days are over. … We don’t want any more of New York’s cast-off players.”56 In early August, Corcoran was released, and spent the winter focusing on becoming a full-time left-handed pitcher in 1887.57

On March 22, 1887, Corcoran signed with Nashville of the Southern League.58 He pitched in three games and fell into controversy. Memphis players Bob Black and John Sneed were paid by gamblers to coax Corcoran to a bar and get him drunk. Corcoran failed to appear for his start on June 30, and betting was high on Memphis. Nashville manager George Bradley was on to the scheme and pitched the game, beating Memphis. Corcoran was fined $50 and suspended.59 On May 9, however, he was on his way back to the major leagues, signed by the Indianapolis Hoosiers, who paid $1,000 to Nashville for his release, and gave Corcoran a $2,000 salary. “He says that he is in first-class form, physically,” the Indianapolis News reported, “and thinks he is as capable of pitching effectively as he ever was — at least he is going to try it.”60

Indianapolis was playing a three-game series in Chicago, so Corcoran went straight there to pitch on May 11. It was a rude homecoming. “‘Little Larry’ who used to twirl for us down on the Lake-Front — faced the champions, and when he stepped into the box it was plain to be seen that he had a great many admirers among the spectators,” wrote the Tribune. “He lost most of them, before the game was over.”61 Corcoran surrendered 11 runs on 12 hits and 10 walks in the Hoosiers’ 11-6 defeat. “Corcoran labored under the fatigue of a long ride from Nashville,” wrote the Indianapolis News.62

Corcoran made his last major-league start on May 17 at New York. “A study of the score is suggestive of profanity,” commented the Indianapolis News on the Giants’ 26-6 win. Ironically, he was “presented a floral harp by his eastern admirers.”63 “It was a sad day for Larry Corcoran,” wrote the New York Herald, “The little favorite was a rattling good pitcher — once.”64 Corcoran played in center field on May 20, his last major-league game, and was released by the end of the month.65

In 1888 Corcoran signed with the London (Ontario) Tecumsehs of the International Association. He played in 28 games, pitching in only six and playing 22 in left field. He was again fined and suspended for intoxication, then was in a fight with teammate Shorty Howe, biting Howe’s finger so badly that the fingernail came off.66 Both players were released, and Corcoran’s baseball career was over. Sporting Life noted at the end of 1888, “Larry Corcoran has come to that dernier resort of decayed ball players — bar-tending. He hands out drinks in a Newark saloon.”67

Corcoran umpired in the Atlantic League in 1890 and the Illinois-Iowa-Indiana League in 1891, but stepped down due to poor health.68 The fledgling Brotherhood of Professional Base Ball Players, an early and unsuccessful attempt to organize a baseball players union, was able to send $300 to Corcoran “in his last days,” Sporting Life reported.69

Corcoran died on October 14, 1891, at the age of 32 at his home at 24 Cherry Street in Newark after suffering for several months from Bright’s disease, a kidney ailment that today is called nephritis. His funeral was held at St. John’s Catholic Church in Newark. He was survived by Gertrude and four children, Margarete, Walter, Mary, and Sarah Corcoran.

Corcoran died broke and was buried in an unmarked grave in Holy Sepulchre Cemetery in Newark. In 2009 Captain John Melody and a group of baseball-loving police officers and firefighters in Essex County, New Jersey, stumbled upon Corcoran’s story on the website thedeadballera.com and raised money for a headstone. It was dedicated in September 2009. “We felt he deserved a gravestone based on his accomplishments in the big leagues,” Melody said. “Plus, his last name was Corcoran, and most of us are Irish, so we felt a connection.”70

This biography appears in SABR’s “No-Hitters” (2017), edited by Bill Nowlin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the text, the author consulted John O’Malley’s article, “Lawrence J. Corcoran,” in Robert L. Tiemann and Joseph Overfield, eds., Nineteenth Century Stars (Phoenix: Society for American Baseball Research, 2012), 63-64. Special thanks also to the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York, for access to Larry Corcoran’s file, and Jacob Pomrenke for research assistance in writing this article.

Notes

1 “Between the Lines,” Boston Herald, November 15, 1891: 22.

2 “Special to the Eagle,” Brooklyn Eagle, April 2, 1897: 4; Peter Morris, Game of Inches: The Story Behind the Innovations That Shaped Baseball (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee Publishers, 2010), 93.

3 “Enterprise vs. Chelsea,” New York Clipper, May 19, 1877: 59.

4 “Base Ball,” Brooklyn Eagle, May 4, 1877: 2.

5 “Livingston vs. Rochester,” New York Clipper, June 30, 1877: 107.

6 “The Springfields for 1879. Something About the Previous Work of the Men Constituting the Nine,” Springfield (Massachusetts) Republican, April 11, 1879: 8.

7 SABR researcher Joseph M. Overfield called the 1878 Bisons “The First Great Minor League Club.” See http://research.sabr.org/journals/first-great-minor-league-club. Retrieved July 28, 2015.

8 “The Springfields for 1879.”

9 “Sporting Matters. Base Ball,” Springfield Republican, May 14, 1879: 5.

10 “Sporting Matters. Base Ball. Exit Springfield Ball Club,” Springfield Republican, September 8, 1879: 5; “Sporting Matters,” Springfield Republican, September 24, 1879: 5.

11 “Sporting Matters. Rowell Wins the Walking Match, with Merritt Second and Hazael Third,” Springfield Republican, September 29, 1879: 5.

12 David L. Fleitz, Cap Anson: The Grand Old Man of Baseball (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2005), 88.

13 Adrian C. Anson, A Ball Player’s Career. Being the Personal Experiences and Reminiscences of Adrian C. Anson (Chicago: Era Pub, 1900), 109-110.

14 Anson, 110.

15 “Sporting. Base Ball,” Chicago Tribune, April 2, 1880: 3.

16 “Base-Ball. Opening of the League Championship Season Yesterday,” Chicago Tribune, May 2, 1880: 7.

17 David Quentin Voigt, American Baseball: From Gentleman’s Sport to the Commissioner System (Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, 1966), 102.

18 “Sporting Events. The Most Extraordinary League Championship Game on Record,” Chicago Tribune, June 5, 1880: 11.

19 “Athletic Amusements. Model Exhibitions on the Base Ball Diamond Yesterday,” Boston Globe, August 5, 1880: 4.

20 “Sporting Events. The League Championship Struggle Resumed on the Chicago Grounds,” Chicago Tribune, August 11, 1880: 3.

21 “Sporting Events. A Game of Ball In Which Boston Scored Neither a Run Nor a Base-Hit,”Chicago Tribune, August 20, 1880: 8.

22 “Sporting Events. Slashing Defeat of the Clevelands by the Chicago Champions,” Chicago Tribune, May 4, 1881: 5; “Sporting Events. Providence Smothered by the Chicago Champions — Score, 8 to 0,” Chicago Tribune, June 25, 1881: 6.

23 “Sporting Events. A Model Game of Base-Ball in Which the Chicagos Were Victorious,” Chicago Tribune, August 5, 1881: 3.

24 “Wild Play and ‘Snake’ Balls,” Inter Ocean (Chicago), August 12, 1881; Morris, 97.

25 “Sporting Events. Chicago Successful in a Twelve-Inning Game Against Detroit,” Chicago Tribune, August 24, 1881: 3.

26 “Base-Ball Games. Return of the Chicago Team for a Series on Their Own Grounds,” Chicago Tribune, June 21, 1882: 8.

27 John O’Malley, “Lawrence J. Corcoran,” in Mark Rucker and Robert L. Tiemann, eds., Nineteenth Century Stars (Kansas City: Society for American Baseball Research, 1989), 31.

28 “Corcoran Was Off Being Married,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 24, 1882: 5.

29 “Base Ball Matters,” Boston Herald, August 29, 1882: 5.

30 An obituary listing “Gertrude A. Corcoran nee Grork, widow of Lawrence J. Corcoran” as having died on March 9, 1898, appeared in the Springfield Republican, March 12, 1898.

31 “Base-Ball Games. Brilliant Close of the Championship Season by the Chicagos at Home,” Chicago Tribune, September 21, 1882: 8.

32 “Sporting. Chicago vs. Boston,” Chicago Tribune, May 23, 1883: 6.

33“Base-Ball. Chicago 9; Boston 0,” Chicago Tribune, July 19, 1883: 8; “Base-Ball. The Cleveland Club Neatly Whitewashed By the Home Team,” Chicago Tribune, August 30, 1883: 2.

34 “Sporting. The Chicago Team Now Clearly in the Lead for the Championship,” Chicago Tribune, September 9, 1883: 3.

35 “Base-Ball. The Champions Defeated in a Close and Exciting Game at Boston,” Chicago Tribune, September 11, 1883: 6.

36 “Placing the Ball,” Chicago Tribune, September 9, 1883: 3; Morris, Game of Inches, 45.

37 “Base Ball. Corcoran Knocked Out,” Inter Ocean (Chicago), December 9, 1883: 19.

38 “To Be Expelled From the League,” New York Times, December 15, 1883: 4.

39 “Corcoran and the Chicago Club,” New York Clipper, December 15, 1883: 647.

40 New York Clipper, January 12, 1884: 727; “At His Old Post,” Wheeling (West Virginia) Register, January 8, 1884: 1.

41 “Baseball. A Game on Skates,” New York Clipper, January 19, 1884: 745.

42 “Sporting News. The Chicago League Team Again Defeated — Providence the Victor,” Chicago Tribune, May 11, 1884: 11.

43 Buffalo Commercial Advertiser, June 17, 1884; cited in Al Kermisch, “Corcoran Pitched With Both Hands in Regular Game,” in Baseball Research Journal #10 (SABR, 1982), 66.

44 “Base-Ball. Chicago, 6; Providence, 0,” Chicago Tribune, June 28, 1884: 6.

45 The feat was tied twice (Cy Young in 1908 and Bob Feller in 1951) and broken in 1965 by Sandy Koufax.

46 “Base Ball. League Club Contests,” Inter Ocean (Chicago), July 16, 1884: 8.

47 “Base-Ball. The Chicago Program for 1885,” Chicago Tribune, October 12, 1884: 15.

48 “All in Sport. The Chicagos Win an Uphill Game From the Willow-Wielders of the Hub,” Chicago Tribune, May 27, 1885: 3.

49 “Sporting Affairs. Anson’s Team in the Lead in the League Championship Race — Corcoran’s Condition,” Chicago Tribune, June 22, 1885: 3.

50 “Diamond Dust,” Inter Ocean (Chicago), July 12, 1885: 3.

51 Henry Clay Palmer [Remlap], “From Chicago. Our Interest in the Game — Al Spalding and the Chicago Club — Larry Corcoran’s Release,” Sporting Life, July 29, 1885: 4.

52 “Corcoran Signs With New York. His Sore Arm Suddenly Healed,” Inter Ocean (Chicago), July 19, 1885: 2.

53 “Baseball News,” New York Times, July 20, 1885: 5.

54 “Baseball. The New-York Team Win a Second Victory in St. Louis,” New York Times, October 9, 1885: 5.

55 “Transfer of a Player,” New York Times, June 29, 1886: 2.

56 “Out-Door Sports. Base Ball,” Washington Daily Critic, July 7, 1886: 1.

57 “Base Ball Briefs,” Kansas City Times, August 7, 1886: 6; “Baseball. Remarkable Pitching Performances in 1886,” New York Clipper, January 29, 1887: 729.

58 “Larry Corcoran Signs With Nashville,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, March 23, 1887: 2.

59 “Around the Bases,” Chicago Tribune, May 6, 1877: 3; New York Sun, May 8, 1887: 14; “Tennessee Troubles,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, May 3, 1887: 2.

60 “A Change Pitcher. Larry Corcoran Engaged,” Indianapolis News, May 10, 1887: 1.

61 “Base-Ball. A Long Game Between Chicago and Indianapolis,” Chicago Tribune, May 12, 1887: 3.

62 “Corcoran’s Trial. Kindly Received by Chicago,” Indianapolis News, May 12, 1887: 1.

63 “Oh, What a Game! The Lamented Corcoran Knocked out of the Box — General Ball Talk,” Indianapolis News, May 18, 1887: 1.

64 “Ball Gossip,” Indianapolis News, May 20, 1887: 1.

65 “Base Ball Gossip,” Indianapolis News, May 23, 1887: 1.

66 “Baseball Small-Talk,” The Critic, June 7, 1888: 3; “Chips From the Diamond,” New York Sun, August 6, 1888: 3.

67 “Notes and Comments,” Sporting Life, December 19, 1888: 2.

68 “Notes and Gossip,” Sporting Life, June 21, 1890: 4; “News, Gossip, and Comment,” Sporting Life, June 27, 1891.

69 “Still on Earth,” Sporting Life, December 12, 1891: 12.

70 Tom Meagher, “Essex County police, firefighters raise money to mark grave of forgotten baseball player,” http://nj.com/news/local/index.ssf/2009/09/cops_raise_money_to_mark_grave.html, retrieved August 1, 2015.

Full Name

Lawrence J. Corcoran

Born

August 10, 1859 at Brooklyn, NY (USA)

Died

October 14, 1891 at Newark, NJ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.