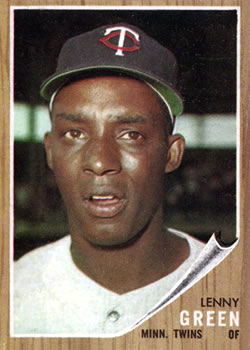

Lenny Green

Scout Joe Krich of the St. Louis Browns followed ballplayer Lenny Green during his days at Detroit’s Pershing High School and soon after Green graduated, Krich signed him on the very last day of 1952 to a contract with York (Pennsylvania) of the Class B Inter-State League. Green never played for York, though, nor for the Browns. His next games were for the Army.

Scout Joe Krich of the St. Louis Browns followed ballplayer Lenny Green during his days at Detroit’s Pershing High School and soon after Green graduated, Krich signed him on the very last day of 1952 to a contract with York (Pennsylvania) of the Class B Inter-State League. Green never played for York, though, nor for the Browns. His next games were for the Army.

Leonard Charles Green (born January 6, 1933, in Detroit) was the middle of three sons born to Eugene and Anna Green. Gene Green worked at the Ford Motor Company stamping plant in suburban Dearborn. Anna ran a flower shop. Lenny’s older brother Willie and younger brother Donald both became teachers. Neither really pursued baseball; Willie ran track in college, and Donald played baseball in high school but didn’t take it any further. Lenny’s father first inspired him to play ball. It came naturally, he explained in an August 2007 interview. “I’ve always liked baseball. My dad liked it. Dad worked for the Ford Motor Company and he played for the plant team. Only in the plants. He mostly played in the outfield. We had good sandlot programs here in Detroit and I got involved in them early.” Lenny himself primarily played outfield.

He played for his high school team and played in the Detroit Baseball Federation at Northwestern Field. Jerry Griffin, a member of the Mayo Smith Society and a contemporary of Green’s, recalls seeing Lenny on the Detroit sandlots: “Lenny was a very graceful athlete, who could run like a deer and was a strong line drive hitter,” Griffin remembers. Green was “the ultimate team player who always had a big smile for everyone he met.” Lenny was drafted into the Army not long after he finished high school and spent two years in the infantry, stationed at Camp Atterbury, Indiana, and Fort Carson, Colorado. He kept up his baseball skills, though: “I played a lot of ball. Billy Martin and Zach Monroe, a lot of guys played. Martin was on my team. We played in the Army tournament in San Antonio, Texas. Willie Mays was there, too. Don Newcombe and them. We all met at the tournament. I played against them. And then the next year, I went down there and played baseball.”

Green was referring to his first assignment in pro ball, coincidentally with San Antonio in the Texas League in 1955, after his discharge from the Army as a corporal. He was still in the same system in organized ball, but since the Browns franchise had relocated from St. Louis after the 1953 season, Lenny was now playing in the Baltimore Orioles chain. With San Antonio he hit .216 as he got his feet wet with 116 at-bats. He downplays his stint in San Antonio: “I never even hardly got on the field. I’d sit there a while and then I went to Wichita. I don’t remember 59 games (laughs). I was there about a month or so. They didn’t give me much opportunity to play. I played a lot when I got to Wichita.” And he took full advantage of the opportunity, batting .302 in 78 Western League games.

In 1956, Green spent the full season with Columbus in the Class A South Atlantic League, which the left-hander led both in batting average (.318) and runs scored (92). After hitting just one home run the year before, he showed some power, hitting 13 for Columbus and driving in what would be a career-high 83 runs. In 1957, Lenny played outfield for the Triple A Vancouver Mounties. Over the course of 505 at-bats, he averaged .311 at the plate (five homers, 57 RBI) and was center fielder on the Pacific Coast League all-star team. On August 25, he was called up to the Orioles and hopped right into action, appearing in both halves of a doubleheader against the White Sox in Chicago. He was 0-for-3 in his first game, and a second-inning error in center allowed Chicago to score the third run of a 6–2 White Sox win. Lenny’s first major league hit came in his fifth game, at Cleveland on August 29. He entered the game in the third inning, replacing Bob Nieman in the lineup, and found himself batting with the bases loaded in the top of the fifth with nobody out. Mike Garcia was pitching for the Indians, and Green tripled to right field, then scored two batters later on Tito Francona’s sacrifice fly. Those were the only four runs in a 13–4 loss. He hit his first major league home run during a September 18 night game at Baltimore’s Memorial Stadium, off Chicago’s Jim Wilson, a solo blast, also in a losing effort. In 1957, Green appeared in 19 games, and hit .182 in 22 at-bats, driving in five runs.

In the winter of 1957–1958, Chico Carrasquel arranged for Green to play ball in the Venezuelan League. Green believes the extra work helped: “I hadn’t had a chance to play regularly in the big leagues, and if you don’t play every day it’s tough…I got my playing in and got a chance to see a lot of pretty fair ballplayers down in South America.” Green broke spring training with Baltimore and appeared in 69 games, playing at all three outfield positions. It wasn’t a productive season offensively, his first RBI not coming until the last day of May. He scored only five runs over the first couple of months, too, batting with an average that declined as the season progressed to the point that he was hitting an even .200 on Memorial Day. He played through July 26, raising his average to .231 but with only four RBI and increasingly as a late-inning defensive replacement who saw only one at-bat in his last 13 games. After the game on the 26th, he was optioned to Baltimore’s International League farm club in Rochester. There, Green completed the season, hitting .261 over his next 180 at-bats.

Green had kept busy, though, and had his own daily sports program—when the team was at home—on Washington radio station WUST beginning in the summer of 1958.

In 1959, he made the big-league club again, and was again used late in games for his first half-dozen appearances. His first start came on April 19 against the Senators, and he had hits in both halves of the day’s doubleheader. Green hit .292 with the Orioles, but not that productively. His only two RBI came on April 26 at Yankee Stadium when he hit a sixth-inning home run off Duke Maas. He scored only three runs, one on his homer. The Washington Senators were looking to replace Albie Pearson, who had been the American League Rookie of the Year in 1958 but was slumping badly in his sophomore season. They wanted Green and dealt Pearson for him May 26. Lenny played for Washington against the O’s in Baltimore the very next day as a sixth-inning defensive replacement. He flied out in his only at-bat. At the time of the trade, the Washington Post called Green “a great fielder with tremendous speed and a better-than-average arm” and revealed that Baltimore had been thinking of releasing him as far back as 1955 but that Orioles manager Paul Richards was so impressed with his defense that he “issued orders to keep Green in the Baltimore organization.”

Green, however, did not enjoy playing under Richards. He was straightforward about it: “I didn’t enjoy playing for him. I didn’t like his managing.” Allowing that “he was a good one, manager and all that, but just.…If you knew him, you either liked him or you didn’t.” Happy to be with Washington, playing for Cookie Lavagetto, Green found a much better situation. With more playing time (he had 190 at-bats the remainder of the season, batting .242 with two homers and 15 RBI), he contributed but was still most highly regarded for his defense. He was lucky to escape serious injury in mid-September when his car struck an ambulance returning from a hospital with such force that Green’s car slammed the ambulance into three parked cars. There were no injuries, and the worst Green suffered was a speeding ticket. The Washington Post’s Shirley Povich reported that Lavagetto considered him sure-handed in the field and the best baserunner on the club.

In the winter of 1959, Green signed to play ball in the Venezuelan League. It was in 1960 that he first broke through offensively, with a very strong .294 season and a .383 on-base percentage. He drove in 33 runs and scored 62 times. Then he found himself in another franchise shift as the Senators resettled in Minnesota as the Twins, while an expansion team began its first year in Washington. Lenny much enjoyed three-plus seasons with the Twins. “I loved it,” he recalls. In 1961, he hit .285 in an even 600 at-bats as the team’s regular center fielder, playing between Jim Lemon in left and Bob Allison in right. He led the club in base hits with 171, hit nine home runs, and drove in 50 runs. Green enjoyed a 24-game hitting streak May 1–28, 1961, which remained the Twins record until Ken Landreaux surpassed it in 1980. Sam Mele took over as manager in mid-June.

In 1962, the Twins made a run for it. Vic Power came in to play first base, and Harmon Killebrew moved to left field. The Twins finished in second place, just five games behind the Yankees in the 10-team league. Green’s .271 was a higher average than those of Killebrew or Allison, but the two flanking outfielders combined for 77 homers and 228 RBI (The Killer led the league in both categories). Lenny hit a career-high 14 home runs and had his best year driving in runs in the major leagues with 63 RBI. Green had a good sense of humor. One Twins fan, accepting the Minnesota Historical Society’s invitation to reminisce about the club, fondly remembered, “One early summer night, the fog was so thick the game was delayed. The crowd roared when Lenny Green ran to center field with a miner’s hat with the light on atop the helmet. The game did eventually resume.”

As did the Twins, Green had an off-year in 1963, batting .239 as rookie Jimmie Hall earned more at-bats. Hall homered a then-rookie record 33 times for the Twins that year. “I knew I was in trouble,” Green later told Boston sportswriter Larry Claflin. “Mele had to keep Hall in there the way he was hitting.” Green still appeared in 145 games, but had only 280 at-bats. His best day came on May 29 in Cleveland, when his two-out, two-run homer in the top of the ninth beat the Indians, 7–6.

In the off-seasons, Green was often invited to team functions and promotional events. In early 1964, he ranked tops among the players in a bowling tournament. He was also one of four Twins players named to an in-house committee to study the problem of planning for racially integrated housing arrangements at their Orlando spring training locale. In 1964, he led the Twins in hitting during the exhibition season but became a well-traveled ballplayer, playing for four teams: the Twins, the Angels, the Hawaii Islanders, and, again, the Orioles. With Jimmie Hall taking over in center, and with Killebrew and Tony Oliva in the outfield, Green was marginalized and spent what must have been a very discouraging first two months with the Twins. He only had 15 at-bats and never once hit safely, though he walked four times and scored three runs. On June 11, he was packaged in a three-team, five-player trade, traveling to the Angels with Vic Power. With only occasional work, he was hitting .184 through July 10 but, as he explained, “I never got a chance to play. They sent me to Honolulu to get in shape.” In 16 late-July games in the Pacific Coast League, Lenny hit .333 with six home runs for Hawaii and was brought back up. Six multi-hit games helped him bring his .184 average up to a more respectable .250, and the Orioles reacquired him for a sum reported as slightly more than the $20,000 waiver price. For the second time, he played his next game against the team that had just traded him. Sold to the Orioles on September 5, he played against the Angels that day, coming on in the eighth to replace Charlie Lau defensively in left. With Baltimore, Lenny hit .190 with just one run batted in during 21 at-bats; and went hitless as a pinch-hitter.

Green was a nonroster invitee to spring training with the Boston Red Sox in 1965, the property of Baltimore’s Rochester ballclub but with Boston on a “look-see” basis. Green had telephoned Orioles GM Lee MacPhail and asked if he could be placed with another team during the exhibition season to see if he could catch on. MacPhail found interest from both Boston and Houston, and Green chose Boston. If he made the team, the Orioles would sell him at a predetermined price, believed to be $25,000. He excelled, leading the Red Sox in spring training with a .385 mark. On March 30 Boston announced his purchase from Rochester. “I had no intention of starting the season with Green in center field,” acknowledged Red Sox manager Billy Herman. “But Lenny hit so well he forced his way in there. He’s a real hustler.” Green kicked off the year for the Red Sox with two home runs on Opening Day in Washington. It was the fourth time Green had hit a home run on an opening day. In 1961 and 1962, he hit homers in the home opener for the Twins, and in 1963 he hit one in the season opener.

Green was the primary center fielder for 1965, between Carl Yastrzemski in left field and Tony Conigliaro in right. His .276 average was a little higher than Tony C’s, but Conig hit a league-leading 32 homers. Green drove in just 24 runs, though two of those came on another day he hit two home runs—June 19 in Chicago. Pitcher Bill Monbouquette appreciated Green’s work; the two round-trippers accounted for the only two runs in a 2–1 win over the White Sox.

This was a season in which the Red Sox drew few customers, and 1966 wasn’t much better—though the team played very well indeed in the second half. They nonetheless finished just a half-game out of last place, and few could have foreseen that they would win the pennant in 1967. “I enjoyed Boston,” Green reflects. “They treated us real nice. I had a real nice time.” On the team, he says, “It wasn’t that we were that bad. We didn’t win like we should have won.”

That there were racial undertones in Boston is undeniable. The Red Sox were the last major-league team to integrate, in 1959, and there were strong suspicions that there was an unspoken racial quota in place. Larry Moffi and Jonathan Kronstadt report a story from Earl Wilson: “When the Red Sox acquired two black players, pitcher John Wyatt and outfielder José Tartabull, on June 6, Wilson told his black roommate, Lenny Green, that there were now too many black players [seven] on the ball club. Although the remark was made half in jest…to no one’s surprise, the phone rang the next morning.” Wilson and Joe Christopher had been shipped to Detroit for Don Demeter and a player to be named later. A week later, Julio Navarro was named as that player. Now Green became a big help to one of the other black players, rookie George Scott. The two become roommates after Wilson left. Scott says, “He was definitely a tremendous help to me…trying to get me to recognize the curve ball and all of that. Lenny was not only good for me, Lenny was good for the Red Sox. He was one of them guys who knew where he was in baseball, and knew what he could do in baseball. And he’d just stretch out and help as many guys as he possibly could. And it wasn’t only the black guys.” Scott thought Green would have become a coach or manager had he played in a slightly later era.

With Yaz fixed in left and Conigliaro in right, Green shared playing time with Demeter, Tartabull, and a number of other outfielders. Limited to 133 at-bats, he hit .241, and with center-fielder heir apparent Reggie Smith waiting in the wings, there wasn’t room for Lenny Green under incoming manager Dick Williams. To no one’s surprise, he was released by the Red Sox on October 21, 1966. “I wasn’t surprised at being released,” he later told the Chicago Daily Defender. “They had to make room for this kid Reggie Smith. He’s a real good one.” Lenny figured he wasn’t quite finished yet. The team he signed with was a surprise, though. It hardly seemed as if the Tigers needed him in their outfield. They had Gates Brown, Willie Horton, Al Kaline, Jim Northrup, and Mickey Stanley—but farm director Don Lund still succeeded in talking Lenny Green into signing a minor league contract with the Toledo Mud Hens, just in case.

Green hadn’t experienced being a free agent before, though. Neither had he won a pennant. Part of Lund’s pitch was that Green could commute back and forth between Toledo and his home in Detroit. The chance that he might get called up and have the chance at last to play for the team he’d dreamed of playing for as a kid was appealing as well. There were the road trips, though, and there were times it seemed a struggle as he told the Washington Post’s Bill Gildea, “Down there, we had to ride a bus almost everywhere. You would think we would have a good bus, but we didn’t.”

With Kaline hurt with a broken finger, once Gates Brown hurt his wrist crashing into the outfield fence, the Tigers put Brown on the disabled list and called up Green on June 30. He’d been hitting .329 for Toledo at the time and kicked off July with the Tigers hitting .429 through the first game of a July 9 doubleheader, with four multi-hit games in his first seven games. “I knew I wasn’t done after Boston,” he told UPI on July 11. “I was gonna keep playing, waiting for a break like this.” He roomed with Earl Wilson, now a star pitcher for the Tigers. Wilson tied for the American League lead with 22 wins in 1967.

Naturally, that initial pace of Lenny’s was bound to slacken, but, asked in mid-July if manager Mayo Smith would have a place for Green in his lineup once Brown and Kaline came back, Smith replied, “Yeah, he will, even if I have to give him mine.” Green was a steady contributor, played for the rest of the season, and hit a very good .278 with 13 RBI. In the season’s last week, Green’s leadoff double in the sixth set him up to score the only run in a 1–0 win September 26 over the Yankees in New York and put the Tigers in a position to tie for the pennant on the final day. Rainouts helped give Detroit a three-day layoff before a pair of weekend doubleheaders at home against the Angels. As the Red Sox listened to the radio to learn whether there would be a playoff against Detroit, the Tigers fell just short in the ninth inning of the last game.

At spring training in 1968, Green was a nonroster invitee at the Tigers’ camp in Lakeland, Florida. He was two weeks short of playing 10 full seasons in the major leagues. Those two weeks of service time could make a major difference in pension plans, but there’s no indication that the invitation was merely an act of generosity. Green had performed very well in 1967 and hoped to contribute again in 1968. He admitted he’d been ready to hang it up after 1966, but was looking forward to the chance to help the Tigers go all the way. “Mayo asked me to come to spring training this year,” he told the Associated Press. “I guess I’ll wind up at Toledo. But I’m in good shape. And next year there will be expansion and some new ball teams.”

It proved to be Green’s last year. He was assigned to the Mud Hens as he expected. He played in 95 games that year, batting .257 with five homers and 28 RBI. And he had one last stint in the big leagues, appearing in six games between June 19 and June 30, four times as a pinch-hitter and twice defensively in left field. He was 1-for-4, and was walked once. Once back in Toledo, he continued to share pointers with some of the up-and-coming Tigers prospects but found he was being used less and less frequently. He had come to the end of the road in baseball.

In 1965, the year after he’d been traded from Minnesota, the Twins won the pennant. In 1966, the Orioles made it—and swept the World Series. In 1967, the year after he’d been released by Boston, the Red Sox won the pennant. Now, in 1968, a little more than three months after he’d last played for Detroit, his hometown Tigers won the pennant and the World Series. Lenny attended a couple of the games, but was no longer part of the team. The Series shares came to a little over $10,000; Lenny and five other bit players were given $200 apiece. Money completely aside, though, did he feel disappointed in some way, left out of the glory? “No, no. I had a good career and I enjoyed it. No, I don’t ever feel left out. I feel blessed to ever have been able to play.”

Green got a job with Ford, like his father before him, after his baseball career was complete and worked as a security supervisor for 27 years. He was not involved in baseball in any way; he told interviewer Ron Anderson that he was never tempted to seek out a managerial or coaching position. It simply wasn’t his priority. He had his fill and wanted to move on. Family came first. He and his wife have one child, a daughter born late in the 1962 season. He had been fully enjoying his retirement from Ford until back miseries necessitated surgery in 2007.

He died on January 6, 2019, on his 86th birthday.

An earlier version of this biography appeared in SABR’s “Sock It To ‘Em Tigers: The Incredible Story of the 1968 Detroit Tigers” (Maple Street Press, 2008), edited Mark Pattison and David Raglin.

Sources

Moffi, Larry, and Jonathan Kronstadt. Crossing the Line: Black Major Leaguers 1947–1959. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press. 1994.

Chicago Daily Defender, August 7, 1967.

The Sporting News, April 24 and May 1, 1965.

The Washington Post, September 19, 1959, and July 12, 1967.

www.mnhs.org/exhibits/baseball/memories.html

Anderson, Ron. Interview of George Scott, August 6, 2007.

Nowlin, Bill. Interview of Lenny Green, August 1, 2007.

Photo Credit

The Topps Company

Full Name

Leonard Charles Green

Born

January 6, 1933 at Detroit, MI (USA)

Died

January 6, 2019 at Detroit, MI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.