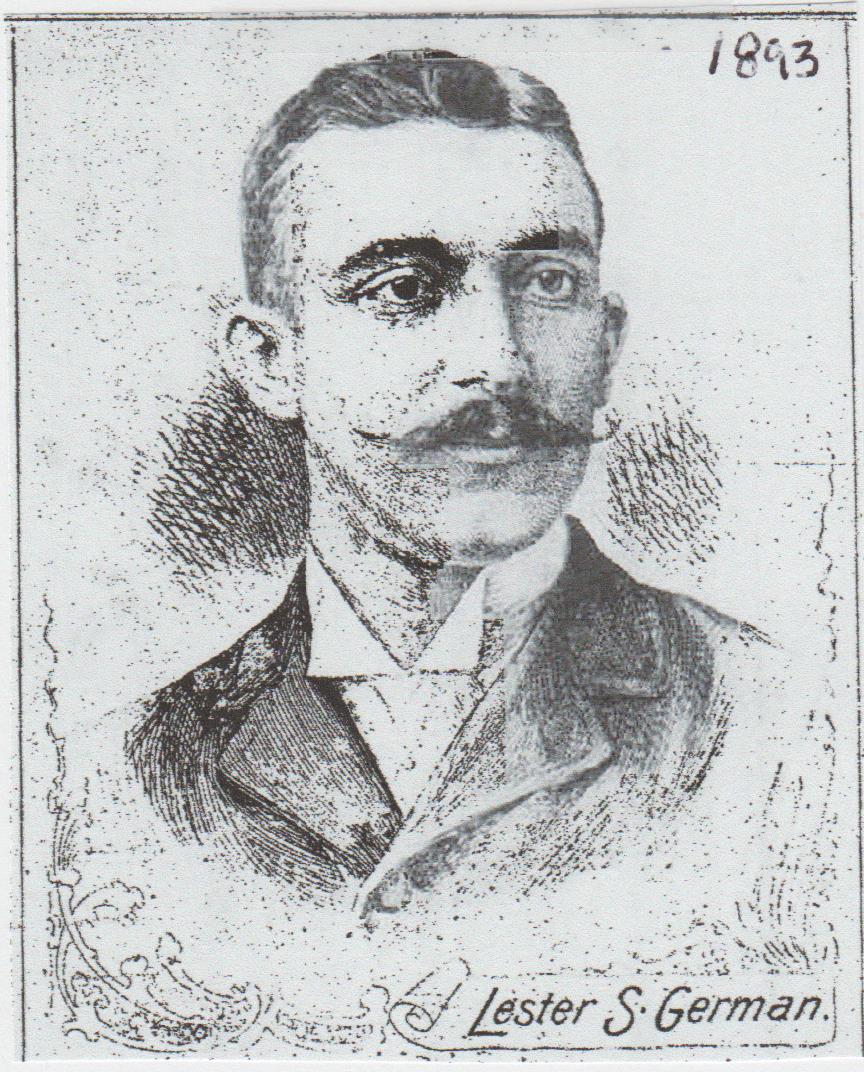

Lester German

Now forgotten, the name Lester German regularly appeared in sporting pages newsprint for almost 40 years. In the early 1890s German was a young right-handed pitcher whose four consecutive 30-win professional seasons made him a hot prospect. But his major-league career, hampered by illness and arm trouble, proved a disappointment. And his underperformance at times left German the object of press disdain, particularly during his three-plus years stay with the New York Giants. His pitching arm rendered near useless by 1896, German left the game after an unsuccessful attempt to convert himself into an infielder.

Now forgotten, the name Lester German regularly appeared in sporting pages newsprint for almost 40 years. In the early 1890s German was a young right-handed pitcher whose four consecutive 30-win professional seasons made him a hot prospect. But his major-league career, hampered by illness and arm trouble, proved a disappointment. And his underperformance at times left German the object of press disdain, particularly during his three-plus years stay with the New York Giants. His pitching arm rendered near useless by 1896, German left the game after an unsuccessful attempt to convert himself into an infielder.

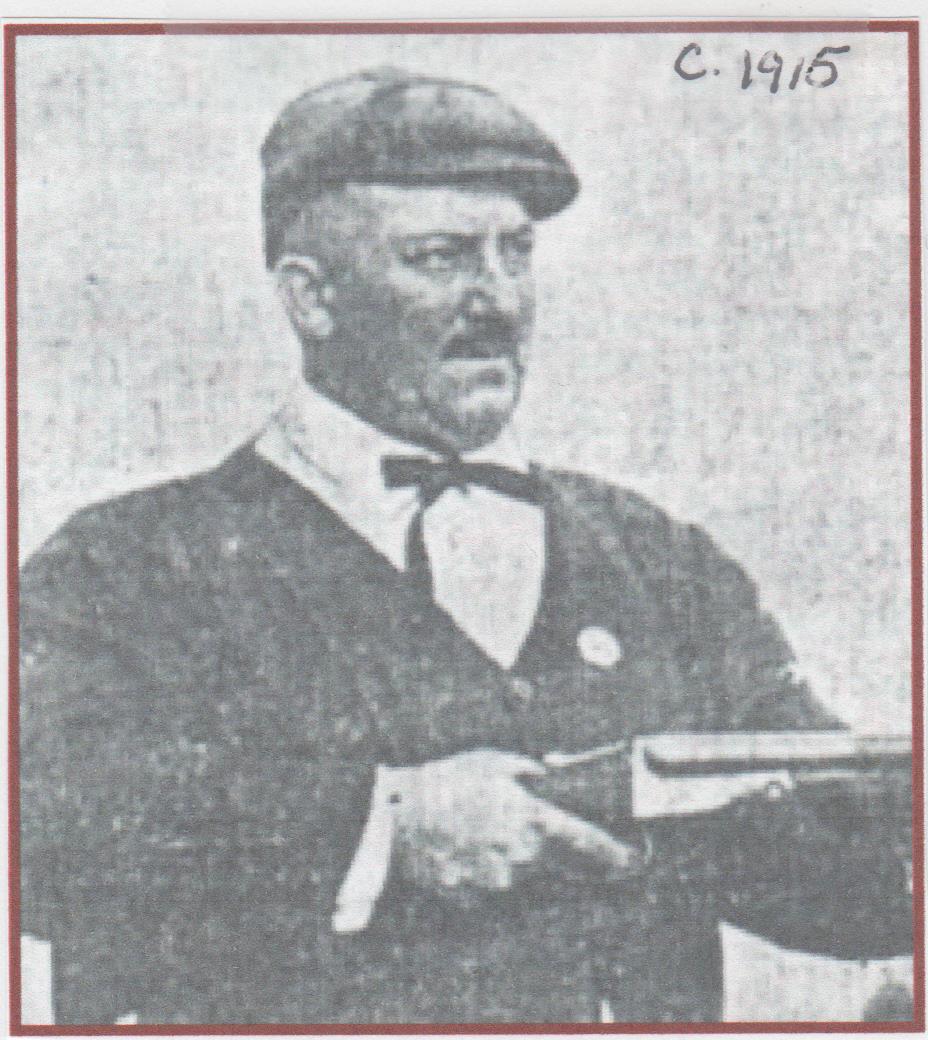

Without seeming to miss a beat, German thereupon transformed his proficiency with firearms into a second career. He began by winning local trapshooting competitions, and by 1911, he had become the national trapshooting champion in both singles and doubles.1 Four years later German set a new world record, knocking 499 of 500 targets out of the air in tournament play. Scribes covering the sport dubbed German “the Ty Cobb of trapshooting,”2 while one expert commentator considered “Lester German possibly the best shot in the world.”3 A formidable marksman well into upper middle age – he won a tournament in his native Maryland as a 56-year-old – German continued competitive trapshooting and promoting shooting meets until shortly before his death in 1934.

Lester Stanley German was born on the outskirts of Baltimore in Aberdeen, Maryland, on June 1, 1869. He was the youngest of three children born to plasterer David H. German (1825-1899) and his wife, the former Mary Forthyse (or Forsythe, 1836-191?), both Maryland natives of English/Scotch-Irish descent.4 As a boy, Lester5 attended school in nearby Mechanicsville through the fifth grade.6 Nothing else is known about his childhood. Like countless others, Lester began his baseball career on hometown sandlots, thereafter developing some local renown as a semipro pitcher. In time, he was entertaining offers from several minor-league clubs.7 In late February of 1888, the 18-year-old German signed with the Allentown (Pennsylvania) Peanuts of the Class B Central League.8 He made his first professional start on April 2, dropping a 12-0 decision (five earned runs) to the reserves of the National League Philadelphia Quakers (Phillies). Allegedly, he also was hammered in his Central League debut, surrendering 22 base hits to Elmira.9 But a three-hit victory over Binghamton then righted the course, and by late May, Sporting Life was describing the 5-foot-8, 165-pound German as “a rising pitcher.”10 Thereafter, Lester became dissatisfied with his $75-a-month salary. And when Allentown management refused to make good on a purported promise of a substantial salary increase, German threatened to leave the club – no idle warning given that he was under age and thus not subject to blacklisting if he departed.11 Whether he was eventually satisfied by Allentown owners or not, German finished the season with the fifth-place (51-51) Peanuts, but his personal log has been lost to time.

At the close of the 1888 campaign, the Central League disbanded, leaving German free to sign elsewhere. He decided to continue his career with the Lowell (Massachusetts) club of the Atlantic Association, signing in March 1889.12 The loss of individual player statistics makes it impossible to assess how German fared overall, but he ended the season on a final-game high note, firing a 12-inning one-hitter in a 2-1 victory over Hartford.13 The stage was now set for the four-season minor-league run that would make Lester German a highly sought after pitching commodity.

German sought his release from Lowell but could not get it.14 Rather, Lowell sold the contracts of German and fellow pitcher Henry Burns to the Syracuse Stars of the major-league American Association, reportedly receiving $1,500 for the pair.15 But when the 1890 season began, German was not in Syracuse. He was a member of the Baltimore Orioles, a longtime AA club recently demoted to the minor league Atlantic Association. Turning 21 during the campaign, German pitched brilliantly. By mid-August he was leading the league in victories (35). In the process, his young right arm logged over 350 innings.16 Then, the first place (77-24, .724) Orioles accepted an invitation to return to the American Association as a replacement for the vagabond Brooklyn Gladiators.

German made his major-league debut on August 27, 1890, dropping an 11-10 decision to the St. Louis Browns, his creditable pitching undermined by defensive work that let in nine unearned runs. From there, Lester forged on, but without the success he had enjoyed earlier in the year. He finished 5-11, with a 4.83 ERA in 132⅓ innings pitched as a major leaguer. Combined, this gave German a 40-win season in 500-plus innings pitched, a staggering total for a youngster throwing overhand. Baltimore placed German on its reserve list for the 1891 season,17 but released him during the winter when the dissolution of the Players League flooded the market with proven major leaguers in search of new employment.18 Subsequently, German signed with the Buffalo Bisons of the Class A Eastern Association, where the previous season near-repeated itself. German dominated enemy batsmen, leading the circuit’s pitchers in wins (35) and pitching percentage (.761), while posting a 1.38 ERA in 404 innings pitched. Buffalo, meanwhile, made a shambles of the EA pennant race, finishing 15½ games ahead of second-place Albany.

Buffalo reserved German for the 1892 season,19 but that campaign would find the young hurler 3,000 miles away. In March 1892 German left Organized Baseball to sign with the Oakland Colonels of the independent California League, a four-club circuit that played an extended warm-weather schedule.20 Here, Oakland field boss Tom Robinson would subject German’s arm to appalling overwork. Sent to the box in 77 of the Colonels’ 177 games, German threw a mind-numbing 655 innings, yet still posted a dazzling 1.38 ERA. For his troubles, he was saddled with a 31-41 record, testament to the ineptness of the crew that surrounded him. In mid-September, moreover, ingrate manager Robinson gave German notice of his release, citing his failure to pitch “winning ball.”21 But no respite was in the offing for Lester, and he soldiered on for Oakland, pitching a 13-inning season-ender on November 25.

The following spring, German escaped to the Southern League, joining the California-based cast of players being assembled by George Stallings for the Augusta (Georgia) Electricians. Remarkably, neither the abuse of his arm nor the alteration of pitching rules – the pitching distance was removed to the current 60 feet 6 inches and the pitcher’s box eliminated – had any apparent effect on German. Anchored to the newly mandated pitching slab and using a windmill windup, he went a handsome 22-11 in 38 appearances (33 complete games) through mid-July. Along the way German threw the first no-hitter in professional play at the new pitching distance – albeit an abbreviated one. On June 19 he held the Mobile Blackbirds without a base hit in a 3-0, five-inning victory, the game then being called because of rain.22 A month thereafter and with the Southern League teetering on the brink of financial collapse, Stallings sold German and batterymate Parke Wilson before the circuit stopped play. Their destination: the New York Giants.23

German returned to the majors in the first game of a July 19 doubleheader against the Boston Beaneaters at the Polo Grounds. He lost 12-6, but the Boston score was inflated by poor Giants defensive work that allowed eight unearned runs. Local reviews were favorable, with the New York Herald declaring that “with any kind of support, German would have won his game,”24 while the New York Tribune found the battery work of German and Parke “most acceptable.”25 In an ensuing testimonial, the New York Commercial declared that “German gives promise of being one of the best pitchers in the league,” informing readers that the recent Giants arrival “has four or five different styles of delivery and a choice job list of curves, drops and rises.”26 By season’s end, the German log stood at 8-8, with a 4.14 ERA over 152 innings pitched. When melded with his Augusta stats, German had posted his fourth consecutive 30-win season, and put another 470-plus innings on his right arm. That meant that over the past four seasons, German had thrown in excess of 2,100 innings, a near-incomprehensible total even by early 1890s standards.

After 1893, Lester German was a different pitcher, one whose performance went into serious decline. But Parke Wilson, his receiver in Oakland, Augusta, and New York, did not attribute German’s deterioration to overuse of his pitching arm. In Wilson’s estimation, a severe offseason bout of typhoid was the culprit. The following spring German was “no longer the pitcher who had hurled Augusta to the pennant,” and he never regained his prior form anytime thereafter.27 An innocent misadventure in the Giants spring-training camp of 1894 became the source of additional grief for German. During an after-practice bird-hunting expedition with catcher Duke Farrell, the two stumbled across a Florida panther that German was obliged to shoot. In short order, the incident became the stuff of at-first amusing satire, but soon degenerated into long-running and mean-spirited shtick by various Sporting Life correspondents, particularly Albert Mott of Baltimore and William F. Koelsch of New York.

The snide Mott/Koelsch references to “the alleged panther shooter” paled in comparison to the mockery of German by New York Herald sportswriter O.P. Caylor, which often bordered on savage. After German mishandled a comebacker, Caylor observed that “Lester played as if it was in his contract not to stop balls that batsmen rolled at him.”28 Later, uncouth postgame conduct witnessed by a supposedly mortified German led Caylor to declare “Lester German is missing!” and issue a faux APB for “the proud, sensitive young man” who Caylor feared had been “attached by the sheriff” for his own well-being or else had “gone home to mother.”29 Looking back over time, the animosity of Caylor and a few cohorts is puzzling. German was an intelligent, amiable hard worker, not given to drink, chasing women, or quarreling with teammates – hardly a natural target for press scorn or censure. Happily for Lester, Caylor and company were exceptions. Generally speaking, baseball writers were kind to German, even when, such as during his coming days with the Washington Senators, his performance was genuinely deplorable.

The snide Mott/Koelsch references to “the alleged panther shooter” paled in comparison to the mockery of German by New York Herald sportswriter O.P. Caylor, which often bordered on savage. After German mishandled a comebacker, Caylor observed that “Lester played as if it was in his contract not to stop balls that batsmen rolled at him.”28 Later, uncouth postgame conduct witnessed by a supposedly mortified German led Caylor to declare “Lester German is missing!” and issue a faux APB for “the proud, sensitive young man” who Caylor feared had been “attached by the sheriff” for his own well-being or else had “gone home to mother.”29 Looking back over time, the animosity of Caylor and a few cohorts is puzzling. German was an intelligent, amiable hard worker, not given to drink, chasing women, or quarreling with teammates – hardly a natural target for press scorn or censure. Happily for Lester, Caylor and company were exceptions. Generally speaking, baseball writers were kind to German, even when, such as during his coming days with the Washington Senators, his performance was genuinely deplorable.

The dark days for German, however, were still a bit in the future. For the time being, he muddled along as a spot starter on an 1894 Giants staff headed by Amos Rusie (36-13) and Jouett Meekin (33-9) at their best. German chipped in a modest 9-8 record in 24 appearances for a second-place (88-44) New York club that went on to sweep the pennant-winning Baltimore Orioles in four postseason Temple Cup contests. German took in the action at his leisure, as neither he nor any other Giants hurler other than the two aces threw a Temple Cup pitch.

The slide in German’s performance became pronounced in 1895. He pitched worse than his 7-11 record, posting a 5.96 ERA over 178⅓ innings, a span during which he allowed (via base hits, walks, and HBPs) some 350 baserunners. By season’s end, German, a good athlete and a fair righty batter, was being tried out at third base. German’s days as a New York Giant were now plainly numbered. Still, one good thing did happen to him that year: marriage to sweetheart Alice May Garretson, an Aberdeen girl who shared her new husband’s interest in shooting. The couple’s marriage would be a congenial one, blighted only by the loss of sons George (born 1896) and Harry (1899), neither of whom survived infancy.

To some local surprise, German made the Giants’ Opening Day roster for 1896. But after one dismal relief outing and a brief demotion to the New York Mets, the Giants’ affiliate in the Atlantic League, he was released. Tongue presumably in cheek, Sporting Life attributed the clean-living German’s ineffectiveness to “too much reading at night.”30 Signed by Washington, Lester had nothing left and proceeded to turn in one of the 19th century’s worst pitching efforts. He went 2-20 (.091), with a 6.32 ERA, allowing 319 baserunners in 166 2/3 innings for a Senators club that played winning (56-53, .514) baseball when someone other than German was pitching. Unlike the situation in New York, however, German was universally well liked by Washington sportswriters and a Senators fan favorite. Thus, when the late-season notice of his release was rescinded by the club, the move was applauded. To his many admirers, Lester’s woeful won-lost record was the product of “unusually bad luck.”31

Now approaching 30, German’s time as a major leaguer was running out. But a second career was beginning to take shape, as attested by German’s winning a local live pigeon shooting contest over the winter.32 Still, he wanted to play ball as long as possible. Given a final chance in Washington, German managed to squeeze three wins out of a dreadful pitching line: 5.59 ERA, 151 baserunners in 83⅔ innings pitched. He also flopped in a brief audition as an infielder. In August 1897 German was released, bringing his six-season major-league career to a close. Whether due to illness, arm abuse, or insufficient ability, he never fulfilled the promise of his early minor-league years. At baseball’s highest level, Lester German had been a marginal talent, going 34-63 (.351) in 130 games. His lifetime 5.45 ERA was high, even for the offensively explosive time that he pitched in. Perhaps most indicative of inadequate stuff, German struck out only 151 batters in 858⅔ innings pitched, while walking 378 and surrendering 1,104 hits. In sum, he simply was not a good major-league pitcher. In fact, he was a better hitter than hurler, posting a respectable .260 (107-for-411) lifetime batting average.

Hoping to reinvent himself as an everyday player, German signed with Buffalo, now a member of the Eastern League. Buffalo, however, wanted him to pitch. He went 1-2 in three late-season games and received his walking papers shortly thereafter. German gave it one last try in 1898, signing with an Eastern League rival, the Rochester Patriots.33 Hampered by charley horses in both legs, he covered little ground as a third baseman and batted .080 (2-for-25) in seven games. Let go once again, Lester German went home to Aberdeen and waited for another call to play ball. It never came.

After that, German reportedly lost interest in baseball.34 Rather, he focused his attention on trapshooting, building a name in the sport by winning local competitions. Meanwhile, he supported himself and his wife by operating a thriving hotel/bar-restaurant in Aberdeen. At some point thereafter, German was engaged by Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show and occasionally participated in shooting exhibitions with celebrated sharpshooter Annie Oakley.35 German turned professional in late 1906, and shortly thereafter was hired to give shooting demonstrations by the Du Pont Powder Company, a leading ammunition manufacturer. Later, he also represented various firearms companies. All the while, German continued competitive trapshooting, appearing in, and often winning, events across the country.

On the domestic front, 34-year-old Alice German died prematurely in 1908. A year later, Lester remarried, taking 18-year-old Aberdeen neighbor Grace Evans as his second bride. Grace, a crack shot herself, would give birth to two children (daughter Ruth in 1911 and son William Crosby German the next year), but the marriage would not endure. By the time of the 1930 US Census, the couple had separated.

In January 1911 German lost the world trapshooting finals in Chicago to his friend and sometimes trapshooting teammate William Crosby.36 Such defeats, however, were rare, and German quickly recovered, capturing the United States professional trapshooting championship in both singles and doubles that June in Columbus, Ohio.37 By 1914, the Washington Post was calling Lester German “one of the greatest marksmen in the world.”38 The following year German’s shooting career, indeed, his life, were placed in jeopardy when he was struck by an accidental discharge from the firearm of an inexperienced competitor during a tourney at the Maryland Country Club. Rushed to a Baltimore hospital, German survived the surgery needed to remove more than 300 shotgun pellets lodged in his head, neck, back, and torso.39 Remarkably, German recuperated in time to set a new world record only five months later, hitting 499 of 500 flying targets at a competition in Atlantic City.40

German continued to be a top-flight trapshooter for another decade, winning local tournaments as late as 1925.41 But eventually age, weight (he had ballooned to 250 pounds), and illness (diabetes) brought his competitive shooting days to a close. Still, he remained active in the sport, instructing young shooters and promoting events through 1933. Estranged from his second wife, Lester was living under the care of his older sister Almeda Steele, a medical doctor, when gangrene appeared in early 1934. He died of complications of diabetes at his home in Germantown, Maryland, on June 10, 1934, at age 65.42 At the conclusion of graveside services, the remains of Lester Stanley German were interred alongside those of his first wife, Alice, and their two infant children at Baker Cemetery in Aberdeen.

Sources

Sources for the biographical detail provided herein include the Lester German player file maintained at the Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York; US Census data; German family tree info posted on Ancestry.com, and various of the baseball and trapshooting newspaper articles cited below. Statistics have been taken from Baseball-Reference and Retrosheet.

Notes

1 Trapshooting is a competitive shooting sport that involves rapid shotgun fire at inanimate targets launched into the air from various distances away.

2 See, e.g., the Middletown (New York) Press, March 5, 1918, and The (Portland) Oregonian, April 21, 1918.

3 See Peter P. Carney, “Trap Shooting Ballplayers,” a National Sports Syndicate column published in newspapers nationwide on or after April 19, 1919.

4 His siblings were older sisters Lillian (born 1858) and Almeda (1861).

5 Modern baseball reference works usually list our subject as Les German, but the nickname Les does not appear in the plentiful contemporary accounts of his sporting activities. He was invariably identified as Lester German by both the baseball and trapshooting press of his time.

6 According to the Lester German player questionnaire submitted to the Hall of Fame Library by his niece Charlotte Garretson Cronin in July 1976.

7 As per an undated, circa October 1893 profile of Lester German published in the New York Clipper and contained in the German player file at the Giamatti Research Center.

8 As reported in Sporting Life, February 29, 1888.

9 As related in the Philadelphia Inquirer, July 23, 1916. Decades after German’s playing career was behind him, the trapshooting press routinely inflated his baseball credentials, fashioning various yarns about his exploits on the diamond. The fact that Elmira did not have a team in the 1888 Central League renders the instant story unlikely.

10 Sporting Life, May 30, 1988.

11 As per Sporting Life, June 27, 1888.

12 As reported in Sporting Life, March 20, 1889, the Boston Herald, May 22, 1889, and the Worcester Daily Spy, March 23, 1889.

13 As per Sporting Life, September 27, 1889.

14 According to Sporting Life, January 29, 1890.

15 As per Sporting Life, February 19, 1890.

16 Baseball-Reference provides no specific innings pitched for 1890 Atlantic Association pitchers, but German’s 42 games/41 starts/40 complete games translate into about 370 innings pitched by him while Baltimore was an Atlantic Association club.

17 Per Sporting Life, October 18, 1890.

18 As per Sporting Life, January 24, 1891.

19 As reported in the Philadelphia Inquirer, October 20, 1891, and Chicago Daily Inter-Ocean, October 21, 1891.

20 As reported in the Baltimore Sun, March 12, 1892, and Sporting Life, March 29, 1892.

21 Sporting Life, September 17, 1892. Manager Robinson was an equal-opportunity slavedriver. Jack Horner, Oakland’s other pitching mainstay, threw 595 innings in 70 appearances, while catcher Parke Wilson was behind the plate for 165 contests.

22 As reported in the Macon (Georgia) Telegraph and The (Columbia, South Carolina) State, June 20, 1893.

23As reported in the Columbus (Georgia) Daily Enquirer, July 13, 1893, Sporting Life, July 15, 1893, and elsewhere.

24 New York Herald, July 20, 1893.

25 New York Tribune, July 20, 1893.

26 New York Commercial as reprinted in Sporting Life, July 29, 1893.

27 As maintained by Wilson some years later in Sporting Life, November 11, 1899.

28 New York Herald, June 13, 1895.

29 New York Herald, August 15, 1895.

30 Sporting Life, June 6, 1896. German was said to be fond of Dickens and Thackeray.

31 The assessment of the Washington Evening Star, September 19, 1896.

32 As reported in the Baltimore Sun, November 27, 1896.

33 As reported in Sporting Life, February 26, 1898.

34 According to Sporting Life, June 17, 1899.

35 See Sporting Life, August 24, 1907, and Linda Childers, “The Wayback Machine: Les German Was a Hot Shot,” June 26, 2011, posted at patch.com/maryland/aberdeen/the-wayback-machine-les-german-was-a-hot-shot. See also, Steve Trout, “Westy Hogans: Who, What, and Why,” Trap and Field, December 1987.

36 As reported in the New York Times, Chicago Tribune, and newspapers across the country, January 15, 1911. The following year, Lester named his only son (William Crosby German) for the victor.

37 As reported in the Philadelphia Inquirer, Cleveland Plain Dealer, and newspapers nationwide, June 24, 1911.

38 Washington Post, July 12, 1914.

39 As reported in the Baltimore Sun and Washington Post, April 25, 1915, and Sporting Life, May 7, 1915.

40 As reported in the Boston Herald, Trenton Times, and newspapers nationwide, September 18, 1915. The previous world record had been 496 out of 500.

41 German won a tournament at the Orioles Gun Club in Baltimore in July 1925, as reported in the Washington Evening Star, July 25, 1925.

42 As memorialized on the death certificate contained in the Lester German file at the Giamatti Research Center.

Full Name

Lester Stanley German

Born

June 1, 1869 at Baltimore, MD (USA)

Died

June 10, 1934 at Germantown, MD (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.