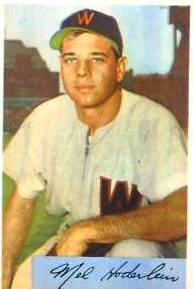

Mel Hoderlein

Was it fate that placed infielder Mel Hoderlein with the 1948 Boston Red Sox rather than the Philadelphia Athletics? Writing in Sports Collectors Digest, Brent Kelley makes the point that Hoderlein probably would have had a much longer big-league career had he been signed to an Athletics contract (that team’s 1948 infield had an average age of 31 and collective lifetime batting average of .261, compared with Boston’s average starting age of 27 and lifetime batting average of .294. Furthermore, the Sox infield averaged more than 100 RBIs a year, and the A’s “maybe 60 in a good year.”)[1] Because the Red Sox lacked the need, Hoderlein perhaps spent four years with Birmingham and Louisville rather than advance earlier to the major leagues.

Was it fate that placed infielder Mel Hoderlein with the 1948 Boston Red Sox rather than the Philadelphia Athletics? Writing in Sports Collectors Digest, Brent Kelley makes the point that Hoderlein probably would have had a much longer big-league career had he been signed to an Athletics contract (that team’s 1948 infield had an average age of 31 and collective lifetime batting average of .261, compared with Boston’s average starting age of 27 and lifetime batting average of .294. Furthermore, the Sox infield averaged more than 100 RBIs a year, and the A’s “maybe 60 in a good year.”)[1] Because the Red Sox lacked the need, Hoderlein perhaps spent four years with Birmingham and Louisville rather than advance earlier to the major leagues.

When Boston did bring him up, it was in mid-August 1951. He appeared in nine games late that year, hit .357 in 22 plate appearances, and showed remarkable patience at the plate: he drew six bases on balls to go with his five hits, for an on-base percentage of .550. It took two trades instead of one, but he wound up with the Washington Senators and spent 2½ seasons with them, batting over 100 points lower (.246) over that span.

Hoderlein was born in Mount Carmel, Ohio, east of Cincinnati, on June 24, 1923. [2] He attended elementary school in Mount Carmel and graduated from nearby Batavia High School. He played American Legion baseball and high-school ball, and, unsurprisingly, it was the nearby Reds who spotted him. He was scouted by Eddie Ries and signed by Fred Fleig. It was 1942. He was 19 and he was sent to the Class D Georgia-Florida League, assigned to the Cordele (Georgia) Reds in a fairly small town (of around 20,000) that supported a ball team. Hoderlein credited his high-school coach, Ed Jucker, as the one who gave him the confidence he would play professional ball.

Hoderlein played shortstop for Cordele, appearing in 87 games and batting .249. He was a switch-hitter. One wonders about the condition of the field; Hoderlein committed 64 errors. The team finished in last place. But the Reds tried him out in Class B at the end of the year, in the South Atlantic League. He gathered 36 at-bats for the Columbia (South Carolina) Reds, batting .389 and hitting his first home run as a professional. He was on a Birmingham contract at the close of the year, but spent the next three years serving in the Army Air Force. He was designated to ship out overseas, but his brother was killed in the service, and the practice in such situations was to keep any siblings Stateside. In 1945, his final year, he played some service baseball, winning a tournament in South Carolina and then traveling to play out west, where his team finished in third place in bigger competition. Mel had married during the war years, to Dorothy Pachuta on May 20, 1944.

After mustering out, Hoderlein was one of the hundreds of returning servicemen who flowed back into baseball in 1946. He was assigned to the Macon Peaches of the Class A South Atlantic League. He hit .278 in 28 games, but grew so homesick that he quit and went back home. After about a month, he returned and was assigned to the Anniston (Alabama) Rams, a Class B affiliate of the Pittsburgh Pirates in the Southeastern League. He got into 34 games with Anniston and hit .325 in the second half of the season. The Rams went on to win the playoffs that year, and that’s where Hoderlein enjoyed the highlight of his career. “We were in the championship game and I was lucky enough to hit a home run to win the final game of the series. The reason I remember it so well – they had a wooden outfield fence and it must’ve been double-walled because the ball that I hit stayed on top of the fence and rolled about 20 feet and then fell out of the ballpark altogether. (Laughs) The outfielder couldn’t get to it, it was up too high, and he was standin’ there walkin’ along with it and it finally went over the other [side].”

After the season Hoderlein was assigned to Birmingham, an Athletics farm team in the Double-A Southern Association. He hit .268 at the higher level of play in 1947, over 314 at-bats. After the season the franchise was bought by the Boston Red Sox and so Hoderlein found himself in the Red Sox system in 1948. He hit .280, saw the Barons win the playoffs, and earned himself a promotion to Triple-A, where he played for the Louisville Colonels for the next three seasons. But had he stayed in the Athletics system, he might have found a quicker route to the top. “Those A’s were all old,” he told Brent Kelley. “They were old men. Do you remember who they were? They were all over the hill – 35, 36. … They were all old-timers and that would have been the place for me to go instead of spendin’ three years in Triple-A. It’s fate, I guess. The A’s wanted to take three of us off Birmingham and Birmingham only had to let ’em have two [as part of the sale of the franchise]. If I could’ve gone with the A’s, I could’ve had a lot more major-league time.”

Hoderlein went to the big-league spring training camp each year from 1949 through 1951, but each year was sent back to the Colonels. With Louisville, Hoderlein saw his average increase each year – from .268 in 1949 to .292 in 1950 and then to .312 (with five home runs each of the latter two years). He made the American Association All-Star team in 1950 and 1951. But the Red Sox had utilityman Billy Goodman ahead of him, and Goodman had a lifetime average of .300, even winning the 1950 batting title. Hoderlein knew he’d have a difficult time ever breaking in with Boston. When Birmingham Barons GM Eddie Glennon told him he’d been selected by the Red Sox, he asked, “Do you think I’m going to beat out some of those guys they’ve got over there?” while also telling Brent Kelley, “It just hurts when you get into an organization that it’s a dead-end and you keep goin’ back to Triple-A ball every year. There are ballclubs you know that you could’ve played on if they didn’t have such good talent right where you were. There weren’t a lot but there were spots that a player of my caliber could’ve walked right in and done the job.”

He still played aggressively, a little too much on at least one occasion. In late May 1949 he was fined $25 for throwing dirt on umpire John Mullen in a game in Indianapolis.[3]

In August 1951 Red Sox second baseman Bobby Doerr was left at home when the Red Sox went out on a road trip, laid low with a sacroiliac condition. Shortstop Lou Boudreau had a broken hand, and third baseman Vern Stephens pulled a muscle on August 14. The team needed another infielder, so they sent for Hoderlein, bringing him up on the 15th, with the gracious help of 10-year-man Al Evans, a catcher, who agreed to take an assignment to the Louisville roster. Mel joined the Red Sox at Shibe Park in Philadelphia on the 16th. Manager Steve O’Neill gave him a start at third base in place of Stephens, who was out for a week. Mel singled in his fourth and final time up. It’s a good thing they got him. For at least a couple of days, he was the only backup infielder they had.[4] He doubled once, tripled once, and drove in a run, finishing with the aforementioned .357 average.

Then came the trades. On November 13 he was traded to the White Sox with pitcher Chuck Stobbs for pitcher Randy Gumpert and outfielder/first baseman Don Lenhardt. It was Stobbs the White Sox were after; the Chicago Tribune said the White Sox had taken Hoderlein “as trade ballast” – though agreeing he was “a fancy fielder.”[5] Mel wasn’t pleased about the trade, since Chicago had Nellie Fox at second and Chico Carrasquel at short. He admitted to Kelley, “I said a few things maybe I shouldn’t have said, like in exhibition games or something I made some comments. Like in batting practice, some of the veterans, they’d stand up there and take 15, 20 swings and we’d get five. … I think that’s one reason they let me go. I would’ve been just a backup infielder, anyhow.” He had missed a good part of the White Sox’ spring training; he’d been hit in the leg by a batted ball and a blood clot developed. Hoderlein was sent from San Antonio to Chicago for better medical treatment, and missed about a month.

On May 3, 1952, never having played in a game for the White Sox, Hoderlein was sent, along with Jim Busby, to the Washington Senators for outfielder Sam Mele. Hoderlein appeared in 72 games and drove in 17 runs, batting .269 and at least initially splitting second base duties with Floyd Baker. He did ruin Maury (Mickey) McDermott’s no-hitter on May 29 with his fourth-inning single off the Red Sox pitcher the only hit of the game for Washington; moments later, he was erased in a double play. He committed only seven errors. Each of the next two years – 1953 and 1954 – Hoderlein played progressively less, and saw his batting average decline, too, with 47 at-bats in ’53 and just 25 in ’54. Bizarrely, he’d held out before finally signing his 1954 contract, despite being offered the same salary he received in a year he had only hit .191. His final big-league game was on June 6, 1954. Eight days later he was traded to the Detroit Tigers with a reported $20,000 for infielder Johnny Pesky.

Thinking back on his time with Washington, Mel said, “I was treated properly, especially by the press. I think I was treated better by the press than I was probably by the ballclub. Bucky Harris was the manager and he had his group, it seemed like. Maybe it’s sour grapes, I don’t know, but the press treated me very well.”

The Tigers placed Hoderlein with the Buffalo Bisons, and he hit .257 in 280 at-bats, playing in 93 games right to the end of the 1954 season. In 1955 he didn’t fare as well, hitting .229 in 201 at-bats. Mel and Dorothy had had their second child (their two sons were Mel Jr. and Bruce Hoderlein), and he developed some back trouble in the wintertime. He decided to pack it in. He recalled the Tigers writing him and wanting him to come back, saying they’d have another position for him once his playing days were done, but he decided to stay and work close to home for the sake of his family.

Taking up work at a manufacturing company, Hoderlein spent 32 years as an electrician at Cincinnati Milling Machine and built a good career for himself. He lost his wife in 1991. He died 10 years later, in the town of his birth, on May 21, 2001. He was 77 years old.

February 8, 2011

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Hoderlein’s player file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the online SABR Encyclopedia, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, and Baseball-Reference.com. Thanks as well to Rod Nelson.

[1] Brent Kelley, “Mel Hoderlein: What could have been,” Sports Collectors Digest, September 23, 1994. Unless otherwise indicated, quotations from Hoderlein himself come from this excellent article.

[2] Standard sources give Hoderlein’s birthdate as June 26 – but all documentary evidence, including his own statements, gives June 24.

[3] Washington Post, May 29, 1949

[4] The Sporting News, September 12, 1951

[5] Chicago Tribune, November 15, 1951

Full Name

Melvin Anthony Hoderlein

Born

June 24, 1923 at Mount Carmel, OH (USA)

Died

May 21, 2001 at Mount Carmel, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.