Pete Magrini

On the surface, it’s difficult to imagine a major-league ballplayer with more disappointing statistics — a pitcher with a career winning percentage of .000, a batting average of .000, and a fielding percentage of .500. But Pete Magrini had six very good seasons in minor-league baseball and, after all, attained a goal that most professional players never do: he played in the major leagues. He enjoyed the time spent pitching, credits his years in baseball with helping him become a success in business, and looks back with great fondness on his playing days.

On the surface, it’s difficult to imagine a major-league ballplayer with more disappointing statistics — a pitcher with a career winning percentage of .000, a batting average of .000, and a fielding percentage of .500. But Pete Magrini had six very good seasons in minor-league baseball and, after all, attained a goal that most professional players never do: he played in the major leagues. He enjoyed the time spent pitching, credits his years in baseball with helping him become a success in business, and looks back with great fondness on his playing days.

Magrini was born to Ancil Magrini and Dorothy (Osheroff) Magrini in San Francisco, California, on June 8, 1942. Ancil was a banker and Dorothy a homemaker. Pete grew up in Santa Rosa, the county seat of Sonoma County. He attended the Santa Rosa schools and graduated from Santa Rosa High School in 1960. He received a BS degree from Santa Clara University.

In a December 2017 interview, Magrini told of his family background: “My father immigrated from Italy with his family at the age of 3 to a tiny town called Duncan’s Mills, California. It was an old railroad and lumber town up by the Russian River. My grandfather worked on the railroad. It’s still there today. Probably the population today is about 80.

“My dad played semipro baseball. He was a first baseman. How he got into that, I have no idea. There was a couple of ball clubs up there in Occidental and Duncan’s Mills. Somebody saw him and saw some good talent, and so he got a scholarship to St. Mary’s College. The scholarship, ironically, was in football but while he was there he hurt his shoulder and turned to baseball.

“My mother migrated from Russia when she was a young girl. She was raised in San Francisco and went to Balboa High School. They met in an office called Commercial Credit, on Van Ness Avenue in San Francisco. I came not too much later.1

“They moved to San Rafael for a short while and then to Santa Rosa. He worked for the Exchange Bank in Santa Rosa, for about 25 or 30 years. He oversaw the entire automobile business in those days — in other words, he called on dealers, arranged flooring with them, and encouraged them to finance through the bank. He was a VP.”

Pete’s mother died when he was 14, and his younger sister was only 7. His father encouraged him in baseball and later helped him to establish himself in automobile sales.

“My dad managed the Santa Rosa Elks, a semipro team in Santa Rosa that was in existence for about 10-12 years. I was a batboy and ended up playing for him.

“His best friend, John Fitzgerald, tutored me all the way through maybe the eighth and ninth grade, and high school. He became the baseball coach at a really powerful high school in Santa Rosa called Cardinal Newman. That’s really my background, between John Fitzgerald, the coach, and my father, the manager. That’s maybe how I got discovered. Scouts started to see me then, between high school and the Elks in the summer.

“I always wanted to be a catcher, but I couldn’t hit. They always said that I had a good arm. Dolph Camilli came out here, because his family was from Santa Rosa. I went to high school with all the kids. He used to come out and have a clinic. I always participated in the clinic and they said, ‘Gee, this kid does have a good arm…but he can’t hit. Why doesn’t he forgo trying to be a catcher and become a pitcher?’ So that’s how that started.”

Pete Magrini played baseball in college and Santa Clara was the runner-up in the National Collegiate World Series at Omaha in June 1962. Michigan won the championship game in the 15th inning on a wild pitch. The sophomore Magrini hadn’t pitched in the ultimate game but contributed in prior games during the finals, starting the penultimate game that eliminated Texas.

On May 13, 1963, he enjoyed a special moment when the Santa Clara Broncos played an exhibition game against the reigning National League Champion San Francisco Giants and beat them, 6-4, in Santa Clara. Nelson Briles, a 19-year-old student at the time, held the Giants to just one hit over the final four innings. Four of Santa Clara’s runs came on walks issued by Giants pitchers. A Giants rally in the fourth inning was squelched when Magrini picked off Ed Bailey at second base and, on another play, a baserunner was cut down trying to steal third base. In another inning he got Felipe Alou to ground into a double play and struck out Willie Mays on three pitches.2

Later that year, Magrini played in Peninsula League winter baseball. In the spring of 1964, he racked up an 11-1 record for Santa Clara and was signed on June 4 to a Minnesota Twins contract by scout Dick Hager of Mountain View, California. It was a momentous week; Magrini was a newlywed, having married Judith LaFranchi five days earlier, on May 31 in Monterey.

“I signed and got married,” he said in 2017. “It’s been 53 years. Still married. Alive and well. We have a son, Peter Jr., who’s 53 and lives in Seattle. Our daughter Lisa is 50 and she lives about three blocks from us in Santa Rosa. We have seven grandchildren.”

Pete was assigned to the Charlotte Hornets of the Double-A Southern League. He threw nine innings over four games, yielding two earned runs, but was then sent to work in Wilson, North Carolina (in the Single-A Carolina League). There he worked in 20 games, nine of them as a starter, and put up a 6-3 record with a 3.00 earned run average.

Magrini was not one of the players protected by the Twins in the November 30 draft, and he was selected by the Boston Red Sox. In the same draft, Boston selected Sparky Lyle.

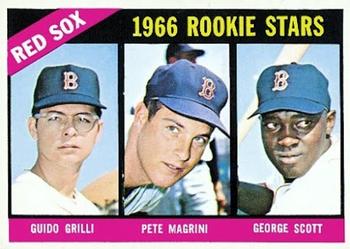

The Red Sox assigned him to their Eastern League affiliate, the Pittsfield Red Sox, for the 1965 season. Under manager Eddie Popowski, Pittsfield won the pennant that year with Magrini pitching the clinching game on September 6. There were two truly standout players on the team — Bill MacLeod, who pitched to a record of 18-0, and third baseman George Scott, who won the Triple Crown, leading the league in batting average, home runs, and RBIs. Magrini had an excellent year, too, with a record of 18-8 and an ERA of 2.26 (which was substantially better than MacLeod’s 2.73).3 Magrini struck out 189 batters. He threw 13 complete games.

In beating the Springfield Giants, 3-1, during the clinching game, Magrini came to the plate in the seventh inning, the score tied, 1-1. He had just four hits in 86 prior at-bats (columnist Ray Fitzgerald called him “one of the worst hitters in the Western world”), with a batting average of .046 — but he singled over second base and drove in the tie-breaking run.4 He held the Giants to six hits.

Magrini stood an even six feet tall and was listed at 195 pounds in a Boston Globe article touting him as a prospect. Noting that six members of his Santa Clara team were in professional baseball, coach John “Paddy” Cottrell said of Magrini, “He’s a big, strong kid who can throw all day and he’s all baseball…[H]is best type of pitch is his breaking stuff…He’s intelligent and has the know-how to make it in the big leagues.”5 “The four who made it to the big leagues,” Magrinin recalled, “were me, Tim Cullen, Bob Garibaldi, and John Boccabella.”

The Red Sox had quite a few young pitchers at spring training in 1966, but were worried that their ace closer, Dick Radatz, wasn’t going to be able to return to effectiveness. They had room for more than a couple of new faces, and manager Billy Herman was going to have something of a youth movement. The Globe’s Roger Birtwell wrote, “Who dreamed the Red Sox this year would come north with pitchers named [Ken] Sanders, Magrini, and [Darrell] Brandon — and that their starting infield — next Tuesday at the Fenway — would include only one man who had reached his 23rd birthday?”6

Magrini himself was still 23, but with added family responsibilities: the Magrinis had a young son at the time, Peter Jr.

He made the team and his first big-league appearance came in the second game of the 1966 season, on April 13. Starter Dave Morehead had surrendered four runs in the first two innings and the Baltimore Orioles had a 4-0 lead when Herman asked Magrini to take over and pitch the eighth. Getting the first batter out, he then hit Frank Robinson, who soon stole second. Brooks Robinson singled, and then Boog Powell singled to second base. Magrini’s fielding support fell apart. A throwing error at second resulted in one run scoring. Another error let the O’s load the bases, then Paul Blair hit a bases-clearing triple. Finally, Magrini closed out the inning, and then set Baltimore down 1-2-3 in the ninth. Nonetheless, he had three earned runs on his record.

Two weeks later to the day, at Fenway facing the White Sox on April 27, Pete came in to relieve Jerry Stephenson in the third. Floyd Robinson had tripled. Magrini got John Romano on a fly ball to center field, but Robinson was able to tag up and score. Then Bill Skowron tripled off the center-field wall, and another sacrifice fly followed. He got through the fourth. In the fifth, he walked leadoff batter Floyd Robinson but then picked him off — except that Robinson got into a rundown and Magrini committed a throwing error that enabled him to reach second. No further damage ensued, but it was Guido Grilli who got the final two outs in the inning, relieving Magrini.

The Red Sox had to cut their roster by one more player by May 12. Magrini figured he might be the man. “I can throw as hard as anyone on this club. I’ve never played Triple A, so if I get sent down it wouldn’t surprise me. After all, I’ve pitched only 4 1/3 innings, and it doesn’t make sense that they’d keep me just to keep the bench warm. I feel very confident I can win a spot on the club. I realize I haven’t done well the few chances I’ve had, but I’m a starter, not a reliever.”7

On May 9, at Kansas City’s Municipal Stadium, three days before the deadline to cut the rosters, he was given a start. Larry Claflin of the Boston Record American noted that Magrini “hasn’t been considered too effective. So this may be his last chance this season.”8

Game time temperature was 36 degrees. He got through the first three innings fine, but the second time through the order, everything fell apart. A walk, a triple, a wild pitch, and a single, and Herman had seen enough. Jim Lonborg was brought on in relief. Lonborg gave up a run-scoring single and then wild-pitched in another run, both charged to Magrini. Kansas City won, 6-1, and Magrini bore the loss. The next day, Magrini was optioned to Toronto, where he did get his chance to pitch Triple-A baseball. Billy Herman said, “That kid did something I’ve never seen before. When I told him he was going to Toronto, he asked me if he could pitch batting practice before he left so he could keep in shape. Most kids, when you tell them they are going back, are too down in the mouth to do anything.”9 Herman told another paper, “He didn’t get a fair chance to prove himself, but he understands…He has a fine chance to become a starter another season and he may even be back this year.”10

Pitching coach Sal Maglie was convinced he’d make the grade.11 Magrini pitched well for Toronto, starting in 20 of 32 games, with an ERA for the year of 3.13. His won-loss record was 7-11. After being named to manage the Boston Red Sox for the 1967 season, Dick Williams — his manager in Toronto — called him “the best relief pitcher in the International League last year.”12 Williams said Magrini “didn’t like being a relief pitcher at first, but later he liked it very much. He became a good one, too. The best in the league.” But Williams didn’t have a great deal of patience. In a March 17 spring training game in Winter Haven, Magrini was called in to pitch the seventh inning and defend a 5-1 Red Sox lead over the Cincinnati Reds. He gave up six runs and lost the game. After the game, though not naming any particular player, Williams said, “I hate to lose, but the pitchers are making my job easier for me. They are eliminating themselves.”13 Sportswriter Claflin wrote in his lede, “Rookie pitcher Pete Magrini eliminated himself from Manager Dick Williams’ plans yesterday….”14 Why had he left Magrini in for so long, to get hammered for 10 hits and the six runs? Williams said, “He’s trying to make this team as a relief pitcher. We gave him a four-run lead to protect and I wanted to see if he could protect it. What if I took him out. Then we would not really know if he could hold a lead or not. We want to find out those things down here and not during the regular season.”15

Two days later, Magrini was optioned to Toronto. Magrini pitched excellent relief for Toronto, working 86 innings in 44 games with a 2.72 ERA. His record was 6-8. On August 3, the Red Sox traded with the New York Yankees and acquired veteran catcher Elston Howard for consideration to be supplied later. The Red Sox first sent Ron Klimkowski and then in mid-October supplied Magrini as well.16 One could argue that Magrini thus, in an obscure way, helped contribute to Boston winning the American League pennant.

Magrini pitched the 1968 and 1969 seasons for the Syracuse Chiefs, the Yankees’ Triple-A affiliate in the International League. He worked exclusively as a starter in 1968, starting 22 games and working 153 innings with a 2.59 earned run average. After a 1969 season in which his ERA rose to 4.17, working primarily in relief, the Yankees placed him on their Double-A roster. He was drafted by the Richmond Braves, but in March 1970 Magrini elected to retire. Yankees farm director Eddie Robinson said, “He wrote me he’d lost his desire to play. That seems as good a reason as any to quit.”17

Magrini had been selling cars in the offseasons working for Zumwalt Chrysler Plymouth in Santa Rosa. That’s where he went to work in earnest, and stayed, rising quickly to become sales manager and ultimately buying the dealership.

“I was in the car business part-time for three years while I was still playing baseball and then when I finished playing baseball, I stayed with the firm and I was with that organization for 33 years — and then my wife subsequently bought it. We sold the dealership in 2000. I stayed in the business until I retired about four years ago.

“It was Zumwalt Magrini Chrysler Plymouth. I started buying it years before. It was Zumwalt Magrini even before we ended up buying the whole thing.”

His father being in banking, specializing in car loans and loans to the automobile industry, had there been some synergy there? “Very much so. When I was very young in the business, I used to call him because he was the banker. He would assist in getting me loans approved so that people could buy the cars.”

Looking back on being a former ballplayer, did he think it helped him in his profession?

“I think what helped me would be the competitiveness. I’ve always been very, very competitive no matter what it is – maybe over-competitive. I was able to take that into the business. I used it daily. I certainly used it when I was coming up through the ranks as a sales manager. Everything I did…every example was usually related to something in sports. Yeah, I think it helped a great deal.”

And Magrini has many fond memories, particularly of his 1965 season in Double A for Pittsfield. As one gets older, he says, people cherish certain memories. He was a member of Rotary for 25 years and still is asked to speak from time to time at different functions. The audience finds it hard to believe what his earnings were compared to what players make today. “When I tell them I was on the higher echelon making $2,300 a month, they just cannot believe it. They can’t possibly put their heads around the fact that the minimum salary having a major-league contract then was $7,200 and today I think it’s $508,000.” One player today makes more than a whole major-league team made in those days.

“But the memories from 1965 would probably rank as one of the best in baseball. Not because I won 18 games but winning the championship, playing with George Scott, spending a lot of time with Bill McLeod, and all of the guys and the families. Everyone was striving to get to the top. Nobody had any money. The road trips, you’d get on the bus and drive all night long and then you’d get your meal money — I think it was a buck and a half or maybe $3.50 a day. It was just a wonderful life. The change was remarkable. Double-A baseball, you were still in pro baseball. The families just loved you. The cookouts and stuff that we had on Sundays at the different families. And the families that were not in baseball but just loved to be a fan, they would have the cookouts. And we would all get together.

“Reggie Smith was on that team. We went to Puerto Rico with the families, for winter ball down there. Reggie was a great guy.

“Eddie Popowski, God bless him, was a miracle man in himself. He had something like 11 or 12 kids. A career minor-league guy. We never knew how the hell he could have that many kids when he was playing baseball all the time – when did he have time for his wife? We used to laugh like hell. He encouraged me. I met some great guys. Yastrzemski. Rico [Petrocelli was a great guy. I had the pleasure of getting to hear Ted Williams during spring training. The memories were fantastic, just fantastic.”

Last revised: January 23, 2018

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Norman Macht and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Magrini’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, and Baseball-Reference.com. Thanks to Rod Nelson of SABR’s Scouts Committee.

Notes

1 Author interview with Pete Magrini on December 14, 2017. Unless otherwise indicated, all quotations directly attributed to Pete Magrini come from this interview.

2 Associated Press, “S. F. Giants Show Broncs How Not to Play Baseball,” Seattle Daily Times, May 14, 1963: 16, and “Broncos Toss Giants, Aided by Young Hurlers’ Wildness,” The Sporting News, May 25, 1963: 9. On the number of pitches involved in striking out Mays, see Joe Cashman, “Morehead, Yaz Balk, 9 More Red Sox Sign,” Boston Record American, February 18, 1965: 23.

3 When it came time for the major-league draft that fall, the Sox protected Magrini and not MacLeod. See John Gillooly, “2-Platoon Baseball Could Save Sox,” Boston Record American, October 27, 1965: 46. As it happens, MacLeod was not selected and remained in the Red Sox system.

4 Ray Fitzgerald, “Pittsfield Sox Win Pennant, 3-1,” Springfield Union, September 7, 1965: 12.

5 Ken Scola, “Magrini One of Brightest Spots in Pitching Picture of Red Sox,” Boston Globe, February 27, 1966: 43.

6 Roger Birtwell, “Sox Go With Kids,” Boston Globe, April 8, 1966: 25.

7 Fred Ciampa, “Rookie Hurler Gets Change To Nail Down Red Sox Job,” Boston Traveler, May 9, 1966: 26.

8 Larry Claflin, “Magrini Koby A’s in 4th,” Boston Record American, May 10, 1966: 3.

9 Will McDonough, “K.C. Wins, 3-2 on Hose Lapses,” Boston Globe, May 11, 1966: 51.

10 Henry McKenna, “Hose Lines,” Boston Herald, May 11, 1966: 36.

11 Larry Claflin, “Tigers Bid for Radatz Fails,” Boston Record American, May 11, 1966: 29.

12 Larry Claflin, “Pete Magrini Possible Sox Long Reliever,” Boston Record American, March 4, 1967: 18.

13 Larry Claflin, “Sox Magrini Belted, 7-5,” Boston Record American, March 18, 1967: 22.

14 Ibid.

15 Will McDonough, “Red Sox Squander Lead, Lose to Cinci in 9th, 7-5,” Boston Globe, March 18,1967: 17.

16 “Sports Roundup: Toronto Pitcher Sent to Yankees By Red Sox,” Boston Globe, October 18, 1967: 43. See also Jim Ogle, “Yanks Hoping Fritz Learns How to Relax,” The Sporting News, November 4, 1967: 44.

17 Jerry Lindquist, “R-Braves Loaded With Veteran Pitchers,” Richmond Times Dispatch, March 22, 1970: 68.

Full Name

Peter Alexander Magrini

Born

June 8, 1942 at San Francisco, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.