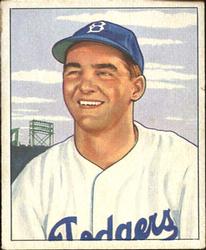

Rex Barney

With the possible exception of Sandy Koufax, no Dodger pitcher ever threw harder than Rex Barney. Throughout the late 1940s, Barney’s fastball was the talk of baseball. In 1947, at the age of twenty-two, he struck out Joe DiMaggio with the bases loaded in a World Series game. On a rainy night at the Polo Grounds in 1948, Barney pitched a no-hitter against the New York Giants and appeared on the verge of realizing his greatness. Alas, it was not to be. “Barney pitched as though the plate was high and outside,” Bob Cooke wrote famously in the New York Herald Tribune.

With the possible exception of Sandy Koufax, no Dodger pitcher ever threw harder than Rex Barney. Throughout the late 1940s, Barney’s fastball was the talk of baseball. In 1947, at the age of twenty-two, he struck out Joe DiMaggio with the bases loaded in a World Series game. On a rainy night at the Polo Grounds in 1948, Barney pitched a no-hitter against the New York Giants and appeared on the verge of realizing his greatness. Alas, it was not to be. “Barney pitched as though the plate was high and outside,” Bob Cooke wrote famously in the New York Herald Tribune.

Born on December 19, 1924, Rex Edward Barney was the youngest of four children of Marie and Eugene Spencer Barney. It was a typical winter night in Omaha, Nebraska—twenty degrees below zero. “My father could not get the old Model T Ford started, so he called somebody to help him rush my mother to the hospital,” Barney wrote in his 1993 autobiography. “She told me I was born in the elevator on the way up to the delivery room.”

Rex’s father worked on the Union Pacific Railroad for forty-five years and eventually became a general foreman. He left home on Sunday night and rode the rails throughout the week before returning on Friday evening. When Rex was born, his sisters, Beatrice and Bernice, were thirteen and eleven, respectively, and his brother, Ted, was nine.

Barney was a star basketball and baseball player at Creighton Prep, a Catholic school for boys in Omaha. He excelled most on the basketball court, leading the team to a pair of state titles and earning all-state recognition. As a high school pitcher, Barney was an angular six-feet-three, 185-pound right-hander who struck out batters by the bushel. He was wild, but that is not unusual at that level. Creighton Prep won the state baseball tournament in two of Rex’s four years.

Barney credited much of his early success to a man he called “one of Nebraska’s greatest high school coaches,” Skip Palrang, who coached every sport at Creighton Prep, managed the city’s American Legion team, and later became athletic director at Boys Town.

Palrang’s formidable presence prepared Rex for his years with the volatile Leo Durocher, first playing for him when he was the Brooklyn manager, and later playing against him when Durocher became the manager of the New York Giants.

The Detroit Tigers, St. Louis Cardinals, New York Yankees, and Brooklyn Dodgers all sent scouts to look at Barney when he was just a sophomore at Creighton Prep. He also began to receive scholarship offers for baseball and basketball from several colleges, most notably Nebraska, Stanford, and Notre Dame.

In the spring of 1943, after Barney’s draft board informed him that he soon would be inducted into the Army, Rex opted to sign a contract with the Dodgers. The signing bonus was $2,500—but all but $500 of that amount was contingent on Barney’s returning from the service and proving he was capable of resuming his baseball career.

Barney enjoyed a meteoric rise through the Dodgers farm system that spring and summer. He reported to Durham, North Carolina, of the Class B Piedmont League in May, and made his debut in relief on June 4 against the Norfolk Tars. His first professional pitch whizzed about five feet above the head of batter Jack Phillips and tore through the chicken-wire screen in front of the field-level press box and conked the local sports editor on the head.

No wonder that sports editor reported, “(Barney’s) pitching was of the compass type—he threw in the general direction of the plate.” Still, the scribe acknowledged, “The lad has plenty of steam and may develop into a pitcher.”

The Dodgers thought so, too. Early on, Durham manager Bruno Betzel took Barney and infielder Gene Mauch aside and told them, “You’re the only two guys on this club with a chance to go up.” Pitching with a dreadful last-place team, Barney won four games and lost six, but his earned run average was a solid 3.00. He struck out seventy-one batters and walked fifty-one in eighty-one innings.

In late July 1943 both Barney and Mauch were promoted to the Dodgers’ top farm club, the Montreal Royals of the International League. Rex appeared in just four games with the Royals and dropped his only decision, but his 2.45 ERA and eighteen strikeouts in twenty-two innings impressed Branch Rickey and the other Dodgers brass. Rex was elevated to Brooklyn for the final five weeks of the season.

As Barney wrote: “The Brooklyn Dodgers, Ebbets Field, and baseball was the greatest triple play God ever executed on this planet. If a player didn’t fall in love with Ebbets Field, there had to be something wrong with him. And those fans—their enthusiasm for their beloved Bums was overwhelming. Today they call it chemistry; I prefer to think of it as a love affair. That’s what made it such a tragedy when the team left Brooklyn.”

The first major-league pitch he threw struck Cubs leadoff hitter Eddie Stanky squarely in the middle of his back. But although he was still nearly four months short of his nineteenth birthday, Rex proved he belonged in the wartime National League, winning two of his four decisions. Barney entered the Army in September 1943 and served at Fort Riley, Kansas, where he played baseball. He and thousands of other apprehensive GIs spent two weeks aboard a troopship, a converted Italian luxury liner, en route from New York to Le Havre, France. Their twelve-ship convoy spent much of the voyage dodging Nazi U-boats; four ships didn’t make it.

Assigned to the Fourth and Sixth Armored Divisions of the Third Army, Barney saw action in France and Germany, took German shrapnel in a leg and his back, and was awarded two Purple Hearts and a Bronze Star. His most memorable encounter, though, was with the fiery American general George C. Patton.

Barney was the commander of a lead tank, roaming the advance positions to draw enemy fire from sunup to sundown. On this day, there was a commotion in the rear, and a Jeep flying four stars pulled abreast. “I recognized him immediately,” Barney told Dick Young of the New York Daily News. “He was my idol. He was sitting behind a 50-caliber machine gun.”

They saluted, and Patton said, “Sergeant, where is the front?”

“General,” Barney responded, “the front of this tank is the front.”

“That’s too goddamn close for me! Carry on,” Patton said, and the Jeep turned around and headed in the opposite direction.

After his discharge Barney rejoined the Dodgers in the spring of 1946. Although the club surprised pundits by challenging the powerful St. Louis Cardinals and tying the Redbirds for the pennant (losing two games to none in the playoff), Rex endured a disappointing year, winning twice and losing five games. Still, the Barney fastball offered considerable promise for 1947.

Just before the start of the ’47 season, Dodgers manager Leo Durocher was suspended “for conduct detrimental to baseball,” and replaced by Burt Shotton. Like Durocher, Shotton was perplexed by Barney’s inability to cure his wildness. Rex reversed his 1946 record, winning five games and losing two. But his strikeout to walk ratio remained a sore point and turned most of his games into nail-biters.

On May 1, 1947 Barney married Beverly Duda, a girl he had known since high school in Omaha, at a Catholic church in Brooklyn. They had two children, Christine and Kevin. The marriage ended in divorce.

For Barney, life on the playing field was far less rewarding, especially late in the season. Nevertheless, Shotton selected Rex to start Game Five of the World Series against the Yankees. For four and two-thirds innings, he allowed just two hits and two runs, but he walked nine batters.

The opening inning epitomized Barney’s career. With no out, the Yankees loaded the bases on a pair of walks, to George Stirnweiss and Johnny Lindell, sandwiched around Tommy Henrich’s double. DiMaggio was due up next.

Coach Clyde Sukeforth walked to the mound and told Barney, in words to this effect: “Nothing to worry about. Just strike this bum out and get the next one to hit into a double play.”

Well, Barney overpowered the Yankee Clipper with a strikeout, got the second out on George McQuinn’s comebacker to the mound, forcing Stirnweiss at the plate, and then fanned third baseman Billy Johnson.

There was more trouble in the third when, with one out, Barney issued consecutive walks to Henrich and Lindell. This time, Rex induced DiMaggio to hit into a 6-4-3 double play.

Pitcher Frank Shea’s run-producing single followed a pair of walks in the fourth. With one out in the fifth, Barney tried to throw another fastball past DiMaggio, but this time the Yankee center fielder hit it into the left-field stands. Shotton replaced Rex with two outs in the inning after he gave up his ninth base on balls. Shea won the game, 2–1; Barney took the loss, and the Yankees went on to win the Series in seven games.

Rex seemed to put it together in 1948, winning fifteen games against thirteen losses, including his crowning baseball moment, the no-hitter against the Giants. Rex ranked second in the league in strikeouts, and he tied for second in shutouts with four. His 3.10 earned run average ranked fifth in the league. This was his only professional season in which he struck out more batters than he walked, 138 versus 122.

But if ‘48 was a personal high for Barney, it was a season of transformation and turmoil for the Dodgers. On July 15 the baseball world was astounded to learn that Durocher, back as manager after his yearlong suspension, had resigned from the Dodgers and replaced the fired Mel Ott as the Giants’ field leader. Shotton, in turn, returned to Brooklyn to lead the Dodgers.

Barney admitted that he was “devastated” to see Durocher go. “I cried when he left. I was used to tough managers and I felt that I had begun to turn things around for him and now he was gone.”

Rex didn’t always see eye to eye with Shotton, but he continued to pitch well. On August 18, he outdueled the Phillies’ Robin Roberts with a one-hitter, winning by a 1–0 score in Philadelphia. The Phillies’ lone hit was a looping single to center by Ralph “Putsy” Caballero in the seventh inning.

Barney’s 2–0 no-hitter against the Giants came on a rainy night at the Polo Grounds. The date was September 9. It had rained throughout the day, but with a sizable advance sale at the gate (36,324), the Giants decided it would be wise to start the game.

The opening inning provided the most angst for Barney. After he walked the leadoff man, Jack “Lucky” Lohrke, on four pitches and retired Whitey Lockman, he fielded Sid Gordon’s slow roller and threw wildly in an attempt to get a force out at second base. Then cleanup hitter Johnny Mize walked and the bases were loaded. But Willard Marshall hit the first pitch to second baseman Jackie Robinson, who started a 4-6-3 double play.

The only other Giant to reach base was losing pitcher Monte Kennedy, on Robinson’s error in the third inning. Barney retired the last twenty Giants in order, capped by Lockman’s foul popup to catcher Bruce Edwards for the final out. Remarkably, only forty-one of Barney’s 116 pitches were wide of the strike zone on this night. Only four Giants went down on strikes.

Durocher, who had been the Dodgers’ manager just weeks earlier but was now the Giants’ field boss, ran past Barney on his way to the clubhouse. “I’m proud of you, kid,” he said to Rex.

Another version of that encounter appears in Peter Golenbock’s book Bums: An Oral History of the Brooklyn Dodgers. Durocher reportedly told Barney: “You skinny son of a bitch. Why’d you have to do this to me? I’m your greatest fan. Why did you do it to me?”

The plate umpire on this memorable evening, Babe Pinelli, called Barney “the fastest thing in baseball today. I don’t care about Lemon or Feller. I’ve seen them. This kid is it. And no finer boy in baseball could have pitched it. He has a heart as big as a lion, and a wonderful disposition.”

Thirty-two years later, in 1980, the New York Baseball Writers presented the “Casey Stengel You-Could-Look-It-Up” award to Barney at their annual dinner in recognition of the last no-hitter at the storied Polo Grounds. No other Brooklyn pitcher ever no-hit the Giants in their own ballpark.

Unfortunately, Barney had reached his peak at the age of twenty-three. With the notable exception of a second one-hitter, against the Chicago Cubs at Wrigley Field on September 19, Rex was a so-so pitcher with the pennant-winning Dodgers in 1949. He won nine games, dropped eight, and his earned run average was a high 4.41.

In the World Series, with the Dodgers trailing the Yankees three games to one, Shotton gave Barney the ball for Game Five. He allowed five runs in two and two-thirds innings and took the loss. The Yankees went on to wrap up Casey Stengel’s first world championship as a manager with a 10–6 victory.

The 1950 season ended in disappointment for the Dodgers when they lost the pennant to Philadelphia on the season’s final day. Limited to twenty appearances and only one start, Barney won two of three decisions, but his ERA skied to 6.42.

Some observers, and Barney himself, believe that a broken ankle, suffered sliding into second base on the final day of the 1948 season, forced him to alter his pitching style. “In 1949 I won nine ballgames, but from then on, by my own admission, I never had the same motion, never had it again,” he told Golenbock. “I never got into the same flow, and in baseball everything is rhythm.”

The Dodgers optioned Barney to Fort Worth of the Texas League in 1951, hoping that manager Bobby Bragan, a former Dodgers catcher, could help Rex learn the strike zone. It did not happen. In five appearances with the Class AA club, he walked thirty-nine batters in just fourteen innings. In a game against Houston, Barney broke the league record for walks given up by a pitcher in a game by issuing sixteen in seven and two-thirds innings.

In 1952 Rex was assigned to the St. Paul Saints, the Dodgers’ farm club in the American Association. His pitching line for the Saints that season read: four games, three innings pitched, no victories, one loss, fourteen walks, seventeen earned runs, and a 51.00 ERA. Barney’s professional baseball career was over. His major-league won-lost record was 35-31, with a 4.34 earned run average. The strikeouts (336) were outnumbered by the walks (410).

At twenty-eight Rex Barney was a has-been. He admitted to contemplating suicide. But then he remembered what Dodgers broadcaster Red Barber had told him a decade earlier: That he had a pleasing radio voice, and should consider getting into broadcasting when his playing career was over.

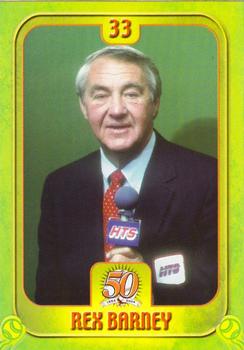

Barney did just that. He started a circuitous climb up the radio ladder—some work in his hometown of Omaha, a 250-watt station in Vero Beach, Florida, some play-by-play work at WCAW in Charleston, West Virginia, the game-of-the-day for the Mutual Broadcasting System. When the Dodgers and Giants went west in 1958, WOR-TV hired Barney and Al Helfer to bring National League games into New York.

With assistance from Lee MacPhail, the Baltimore Orioles’ general manager who had been an office boy during Rex’s early Brooklyn days, Barney began a sports talk show in Baltimore in 1965. He became a celebrity in his adopted city.

During the late 1960s he began filling in for Bill Bolling, the public address announcer at Memorial Stadium. When Bolling departed in the spring of 1973, Barney became the Orioles’ regular PA man, a job he held during the move to Camden Yards and until his death on August 11, 1997. He is buried in Lorraine Park Cemetery, Woodlawn, Maryland.

During the late 1960s he began filling in for Bill Bolling, the public address announcer at Memorial Stadium. When Bolling departed in the spring of 1973, Barney became the Orioles’ regular PA man, a job he held during the move to Camden Yards and until his death on August 11, 1997. He is buried in Lorraine Park Cemetery, Woodlawn, Maryland.

His trademark sign-off, “THANK Youuuu,” and cry of “Give that fan a contract,” after a spectator made a nice play in the stands, became part of the Baltimore culture. “His voice was almost like a security blanket,” said Mike Flanagan, the former Orioles twenty-game winner and now a television announcer.

Barney’s last years were plagued by ill health. He suffered a stroke in 1983 and a heart attack in 1991, one year before he had a leg amputated because of circulation problems associated with diabetes. His second marriage, to a Baltimore schoolteacher named Carole Bennett, also ended in divorce.

“I should have been up there with the greats,” he wrote in his autobiography. “I should have gone right up the ladder, but too many rungs were missing.”

Sources

Barney, Rex, with Norman L. Macht. Rex Barney’s THANK Youuuu for 50 Years in Baseball from Brooklyn to Baltimore, Tidewater Publishers, 1993.

Barney, Rex, with Bill Roeder. “Can’t Anybody Help Me?” Collier’s, April 16, 1954.

Corio, Ray. “Rex Barney, 72, Dodger Pitcher; Threw a No-Hitter for Brooklyn,” New York Times, August. 13, 1997.

King, Larry. “Rex Barney:” Alive, Well and Talkative,” Sporting News, May 28, 1984.

Madden, Bill. “A Baseball Voice is Silenced: Rex Barney Dead at 72; Ex-Dodger, Announcer,” New York Daily News, August. 13, 1997.

Young, Dick. New York Daily News, Sept. 10, 1948.

Baseball Guide and Record Book, Charles C. Spink & Son, 1944, ‘48, ‘49, ’50.

Rex Barney player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, Aug. 12, 2009.

Full Name

Rex Edward Barney

Born

December 19, 1924 at Omaha, NE (USA)

Died

August 11, 1997 at Baltimore, MD (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.