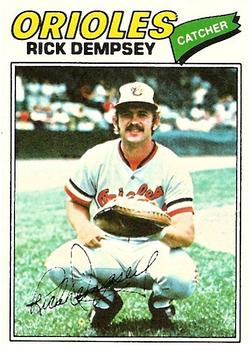

Rick Dempsey

The routine remains one of the enduring spectacles in modern baseball history: In a heavy downpour, with the infield covered by a tarpaulin and the fans huddled beneath umbrellas or hunched over in ponchos in an attempt to ward off the rain, the second coming of Babe Ruth approaches home plate with the same small, mincing steps made famous by the Bambino, and takes his place in the batter’s box. With a protruding belly produced by towels stuffed down the front of his jersey, the slugger waggles his bat and then points it toward the farthest reaches of center field, as Ruth is mythologized to have done in the 1932 World Series. Despite the driving rain the fans remain in their seats; they’ve seen this act before, but it never fails to entertain.

The routine remains one of the enduring spectacles in modern baseball history: In a heavy downpour, with the infield covered by a tarpaulin and the fans huddled beneath umbrellas or hunched over in ponchos in an attempt to ward off the rain, the second coming of Babe Ruth approaches home plate with the same small, mincing steps made famous by the Bambino, and takes his place in the batter’s box. With a protruding belly produced by towels stuffed down the front of his jersey, the slugger waggles his bat and then points it toward the farthest reaches of center field, as Ruth is mythologized to have done in the 1932 World Series. Despite the driving rain the fans remain in their seats; they’ve seen this act before, but it never fails to entertain.

The batter soon gets a pitch he likes. With a tremendous Ruthian swing, he drives the imaginary ball and takes off for first base. Depending on the outcome of the hit, the runner may belly-flop or pratfall into each base or circle them all in an exaggerated reenactment of Ruth’s home run trot. Regardless, though, the finish is always the same: a face-first slide into a huge puddle at home plate, creating an enormous spray of water that often reaches all the way into the stands. But the crowd never seems to mind; the Baseball Soliloquy in Pantomime1 they’ve just witnessed is the most enjoyable rain delay they’ve ever endured.

Rick Dempsey always was a crowd favorite. Whether he was entertaining during rain delays or fronting his lip-syncing four-man Orioles band on the field while Bob Seger’s “Old Time Rock and Roll” blared from the Memorial Stadium public-address system, Dempsey endeared himself to the Baltimore faithful. “I was a blue-collar catcher,” he reminisced in an Orioles history published in 2001; “down there in the trenches with the fans, fighting and scrapping just to break even. I intermingled with the fans. … I think they appreciated my approach to the game. I might dive into the grandstand or dive into the dugout to catch a ball. … I never played it safe.”2 Dempsey he parlayed that reckless style of play into one of the longest careers in baseball history.

As a 13-year-old on his Canoga Park-Woodland Hills, California, Pony League team in 1963 (which went to the Pony League World Series finals in Washington, Pennsylvania), Dempsey could hardly have imagined that one day he would be one of the premier defensive catchers of his era and one of only three (with Carlton Fisk and Tim McCarver) to play in four different decades in the major leagues; or that his career would last 24 seasons, the eighth highest total ever. It assuredly would have seemed equally far-fetched to consider that he would catch the most games (1,230) in Orioles history, play on three World Series teams or win a World Series Most Valuable Player award. Yet as Dempsey told an interviewer in 2008, “I went off to work when I was 17 years old and I focused on professional sports … and I knew that if I got hurt, or that if I didn’t make it, it was going to be a long hard trail for me to get anywhere in life, and so that’s what motivated me more than anything else. … I wasn’t afraid of hard work.”3

More than four decades after he first went to work, Dempsey was still on the job.

When he gave that interview, Dempsey was being inducted into the Crespi Carmelite High School Hall of Fame, in Encino, California. It was there, in 1967, that the 17-year-old from the small Catholic institution had been named the catcher on the Camino Real All-League team after leading his Crespi squad with a .466 batting average. By then, a local newspaper wrote, Dempsey was “one of the finest catchers playing high-school ball in [the] area,”4 and was “considered a definite major-league catching prospect.”5 In June of that year, Jon Rikard Dempsey was a 15th-round draft pick of the Minnesota Twins.

For such a low selection the young man rose quickly through the Twins’ minor-league system. Though Dempsey struggled throughout his career to find consistency as a hitter, by all accounts his defensive skills were in minimal need of polishing. Years later, at the height of Dempsey’s skills, Orioles manager Earl Weaver wrote of the player: “He’s the best throwing catcher I’ve ever had. He gets rid of the ball so quick and he’s accurate … also amazing on pickoffs. … I’ve never seen anybody throw better.”6 Likewise, longtime Oriole public-address announcer Rex Barney, a former major-league pitcher, wrote of the catcher that “concentrating on throwing runners out and getting base hits may have overshadowed his ability to call a game.”7 Indeed, once drafted, Dempsey wasted little time putting his defensive skills on display.

The 1968 season was very successful for the young Minnesota prospect. After a 40-game introduction the year before with Minnesota’s Gulf Coast Rookie League club, Dempsey began his first full minor-league campaign with the pennant-winning Auburn Twins in the New York-Pennsylvania League, where he was named to the league All-Star squad and was chosen the Rookie of the Year (he finished the season with Wisconsin Rapids, in the Midwest League.) After the season the Twins’ assistant farm director, George Brophy, referred to the 19-year-old Dempsey as “a good looking prospect” in need of “more seasoning.”8

After attending spring training with the Twins in Orlando, Florida, Dempsey departed in March 1969 for four months’ military duty. Upon his return, he reported to Wisconsin Rapids and produced, albeit in only 50 games, offensive numbers he’d never again approach: a .364 batting average and .583 slugging. Then in September, after just 258 minor-league games, the catcher was called up by the Twins. On September 23, 1969, at Kansas City, the day after the Twins clinched the Western Division title, Dempsey replaced catcher John Roseboro in the fourth inning, and in his first major-league game he singled in his second at-bat. One week later, at home against the Chicago White Sox, Dempsey led off the ninth with a single and eventually scored the winning run with a head-first slide.

“Dempsey looks like a great prospect,” opined his manager, Billy Martin, after that game. “I like the power of this little guy (he was 6 feet tall and weighed 190 pounds).”9 He wasn’t on the Twins’ postseason roster, but was awarded $400 from the players’ share.

Over the next two seasons, with the exception of two more September call-ups, Dempsey was the starting catcher for the Charlotte Hornets in the Southern League. In 1972 he finally made the Twins out of spring training (at a salary of $9,000), but after playing in just 25 games and batting .200, on July 1 he was demoted to Tacoma, where he finished the season. That proved to be the end of Dempsey’s Minnesota career: on October 31, 1972, he was traded to the New York Yankees for outfielder Danny Walton.

Toward the end of 1973 spring training the Yankees sent Dempsey to Triple-A Syracuse. It turned out to be Dempsey’s last season in the minor leagues. In1974 he was out of minor-league options. In spring training Duke Sims won the role of backup to the durable Thurman Munson, but Dempsey was kept on the roster as the third catcher. Once the season began he didn’t get into a game until he was inserted as a pinch-runner on April 20.

One day early in the season he approached manager Bill Virdon to vent his frustration over a lack of playing time. “I wasn’t playing and I was upset about it,” he said. “We had a little talk. I just told him I’d like a chance to show what I can do. I just felt like playing.”10 In response, Virdon told the fiery young catcher to be ready when the chance came.

It came sooner than Dempsey may have expected. On May 7 New York traded Duke Sims to the Texas Rangers, and Dempsey finally found himself as the Yankees’ number-two catcher. Shortly thereafter, when Munson was forced to the bench with a hand injury, Dempsey filled in and went 8-for-14 in three games, including a double, a home run, and six RBIs, which earned the admiration of his manager. “He’s got some plusses,” Virdon said. “He can do some things and he has shown a lot of people what he can do.”11 For the remainder of that season and all of the next, Dempsey happily played the role he’d worked so hard to achieve.

The blockbuster deal that took Dempsey to Baltimore occurred on June 15, 1976. At the time, the Yankees, playing in refurbished Yankee Stadium and well on their way to drawing 2 million in attendance, held a 12-game lead over the second-place Orioles. Having gone without a pennant since 1964, New York’s management was desperate to win, and was willing to trade youthful prospects for proven veterans. The Orioles, meanwhile, had two pitchers who were recalcitrant holdouts: Ken Holtzman, who was the key player in the trade, and Doyle Alexander. Baltimore’s management was anxious to get rid of both. Accordingly, Baltimore sent the two pitchers, along with another pitcher, Grant Jackson; catcher Elrod Hendricks; and minor-league prospect Jimmy Freeman to New York in exchange for pitchers Rudy May, Dave Pagan, Tippy Martinez, and Scott McGregor, as well as Dempsey. The Orioles thus obtained two pitchers (Martinez and McGregor) who became key contributors on two World Series teams, and the player (Dempsey) who for the next ten years came to represent the heart and soul of the team.

None of the players may have been as important an acquisition as Dempsey. As Orioles general manager Hank Peters remembered years later in the team’s oral history, “Our catching was awful. We had (Dave) Duncan and Elrod (Hendricks), and both were finished. We had the worst catching in the league.”12 At the time of the trade, Peters told The Sporting News that “[w]e’ve had an interest in Dempsey for some time and feel that he could become a sound everyday player.” … We think Dempsey can strengthen our catching.”13

Dempsey was initially unhappy to leave New York. “I really didn’t think the trade was a great opportunity for me,” he remembered years later.14 Being part of a first-place team and seemingly poised to make his first playoff and World Series appearances, Dempsey “loved all those guys on the Yankees, even though I was a role player, a backup to Thurman Munson. I couldn’t look far enough ahead to see that it was a great chance for me to become a first string catcher. I was strictly thinking about the season we were having in New York.”15 That he almost immediately had disagreements with Earl Weaver didn’t make Dempsey’s disposition any brighter.

Perhaps nothing epitomized Dempsey’s Baltimore career more than his often-stormy relationship with the Orioles’ legendary manager. In retirement Dempsey reminisced that throughout their years together, “Weaver tried to humiliate me every day. When he got tired of yelling at the pitchers, he came looking for me. Every single day … he pounded on me as hard as anyone’s ever pounded me. He always said things to me so that the pitchers and other players could hear him. It took me eight years to figure it out. He wasn’t mad at me; he just wanted to make a point to everyone, and he knew I could take it.”16

Once Dempsey eventually established himself as the Orioles’ everyday catcher and team leader, nothing provoked as many arguments between the two men as Dempsey’s playing time … or lack of it. The Orioles’ catcher (career batting average .233) never stopped trying to improve himself at the plate. Each year Weaver looked for an offensive upgrade at that position, and the opposing aims of such fiery competitors almost always produced friction. Once, after Weaver removed him from a game, Dempsey and the manager threw shinguards and a chest protector at each other in the dugout; another time, Dempsey threw Weaver down the dugout steps after the manager pinch-hit for him. As Rex Barney, who knew Dempsey well, explained, Dempsey “thought he should catch every game in spring training, every inning of every day of everything in baseball. Nobody else should even be allowed to put on the glove.”17 Or, as Thomas Boswell of the Washington Post succinctly wrote: “(T)he battle between the two was constant. Dempsey always wanted to play. Weaver always wanted to platoon him.”18

In the beginning, though, Dempsey simply wanted to get on the field. When the catcher joined Baltimore, he later recalled, “Earl didn’t seem happy to have me.”19 At the time veteran Dave Duncan was the popular choice of the Orioles starting pitchers, and Weaver intimated to the new arrival that “[Duncan is] going to play pretty much every day until I can find a spot to get you in there.”20 Said Dempsey, “I thought it was a pretty big slap in the face.”21

It took a week after the trade before he got into a game. “I joined the Orioles in Chicago, didn’t play, went to Minnesota, didn’t play,” Dempsey remembered in 2001. “We got home, and I checked into a Best Western out on the Beltway. It was hot and humid, about 3 o’clock in the morning. I was tired and depressed. I got to the hotel with my two suitcases that were heavy, and I walked across the parking lot about half a mile and dragged all my luggage up to the second floor and all the way to the end of the hall, only to get there and find out they didn’t give me the right key. I walked back down the hall, went outside on the balcony, and threw my luggage down into the parking lot and sat down on the top steps and just cried. “I couldn’t believe it had come to this. Not only had I been traded to a second-place team … but I hadn’t even played for them in my first week there.”22

Toward the end of that first week, however, general manager Peters intervened. “When we got Dempsey,” Peters later reminisced, “Earl wasn’t catching [him]. Finally I sat down with Earl and told him, ‘Earl, I didn’t make that deal to get Dempsey to sit on the bench. … Duncan’s not going to be here next year, and Dempsey will. You’d better start to catch him.”23

And the next day, said Dempsey, “I was in the lineup, played my first game against Kansas City [it was actually Boston], and threw a couple guys out stealing, which was what they wanted me to do. And from then on I was the regular catcher for the next ten years for the Orioles. … It was a great trade, really set up the pitching and catching. … I may have looked like the weak link in the deal at the time, but it was a pretty solid deal for them.”24

Indeed it turned out to be. Beginning the following season, Dempsey spent the next ten years durably anchoring a pitching staff that led the Orioles to two World Series appearances and one championship, a period during which, he said, “We didn’t have great talent, but we had a great team.”25 From 1977 through 1986, he averaged 118 games played per season (in 1977 Dempsey missed six weeks after his hand was broken by a Don Gullett fastball; and in 1981, during which the players struck for two months, the catcher played 92 games), and never finished lower than fifth in games played by American League catchers. He led the league in fielding percentage in 1981 and 1983, and for four consecutive seasons (1977-1980) he never finished lower than third in throwing runners out (he led the league in 1977).

Dempsey never had comparable success at the plate. When he arrived in Baltimore, he brought with him a lifetime average of just .231 and OPS of .597, and he spent the rest of his career working diligently to improve his offense. While his defense had propelled him to the big leagues, as a hitter Dempsey remained largely untutored. Indeed, during his first spring training with the Orioles, in 1977, when he responded well to the mentoring of hitting coach Jim Frey by aggressively stroking line drives to left and center rather than occasionally “pushing them to right field,” Dempsey said, “I always thought I could be a better hitter, but no one ever took the time to work with me. In New York they just didn’t have time for it, or maybe they didn’t know there was so much to teach.”26

The catcher always remained a willing pupil. He tinkered constantly with his batting mechanics. During the first week of the 1980 season, when two Dempsey home runs hinted at the influence of an offseason weightlifting program, hitting coach Frank Robinson said some of Dempsey’s newly found power could also be attributed to the fact that “during the spring I told him we were going to work with one stance, not 25 or 39 different stances (as Dempsey was wont to try). I want him to stay with the one that’s comfortable.”27 After Weaver frequently platooned Dempsey with a left-handed power hitter the next two seasons, in the spring of 1982 Dempsey, by then 32, even experimented with switch-hitting, an exercise, wrote Tom Boswell, that “in the end, by much diligent labor,” turned the catcher “into the worst left-handed hitter in history.”28 On Opening Day that season, in fact, Weaver allowed Dempsey to bat left-handed, so that Dempsey would, in Weaver’s words, “make a fool of himself and be done forever.”29

Weaver succinctly summed up Dempsey’s trials in the batters’ box: “Rick always seems to be saying, ‘Why me?’ ” wrote the manager in his autobiography. “[He]’s just always fighting himself up there.”30 Nevertheless, for much of the catcher’s tenure, he was as integral to the team’s success as any of their home-run hitters.

For all his regular season struggles at the plate, Dempsey shined in postseason play. In 1979, when the Orioles swept California in three games only to lose to Pittsburgh in the World Series, he batted a combined .323 and accumulated an .816 OPS, following a regular season when he had produced just .239/.658. Then, in 1983, in the highlight of his career, Dempsey followed a dismal .231/.634 regular season by producing a .385/1.390 performance in the Orioles’ five-game World Series victory over Philadelphia, for which he was named the Series’ Most Valuable Player. Finally, at 38, after he had left the Orioles, Dempsey posted a combined .300/1.016 performance for the Los Angeles Dodgers in a playoff win over the New York Mets and their 1988 World Series victory against Oakland. All told, in three World Series, Dempsey batted .308/.936 and helped lead his teams to two championships. Somewhere along the line, Dempsey had absorbed all that his hitting coaches had imparted.

The 1986 season turned out to be Dempsey’s final full season in a Baltimore uniform. Despite hitting a career-high 13 home runs, the 37-year-old Dempsey batted just .208, (.122 with men in scoring position and .175 against right-handed pitching), and the club elected not to pick up a $600,000 option for 1987. Instead, they offered Dempsey a one-year deal for $250,000. When the catcher declined, he became a free agent, and Dempsey’s 10½-year tenure with Baltimore was ended.

Despite his poor offensive showing in 1986, Dempsey had still played his customary stellar defense, ranking fourth in the league in fielding average. So in 1987, Cleveland, needing a veteran to mentor young catchers Andy Allanson and Chris Bando as well as compete for the starting job, signed Dempsey to a one-year contract for $400,000. Then in July in Kansas City, Dempsey was bowled over at home plate by 235-pound Bo Jackson and the catcher’s thumb was broken, effectively ending both his season and his Cleveland career.

The following season the Dodgers invited Dempsey to spring training as a nonroster player and he made the club, signing a one-year contract (the Dodgers won the World Series that year) and two subsequent one-year deals. On August 23, 1989, Dempsey led off the 22nd inning at Montreal with a home run to give the Dodgers a 1-0 victory; and on May 18, 1990, in Los Angeles, the 40-year-old, who came into the game with only ten at-bats for the season, hit two home runs against Philadelphia in a 4-2 Los Angeles victory. After that season Los Angeles declined to offer him arbitration, and the catcher was again a free agent.

At age 41, Dempsey signed to play the 1991 season with Milwaukee. He began to yearn for a chance to manage. As the season wound down, it became apparent that Brewers manager Tom Trebelhorn was not going to retain his job, so Dempsey approached owner Bud Selig and asked for a chance to replace Trebelhorn, telling Selig, “I can manage this club; I know what they need.”31 Selig, though, was looking for a manager with experience, so Dempsey wasn’t considered for the job. When the season ended, Dempsey was once more on the market.

Perhaps he would finally have time to watch his son. In 1989 Dempsey’s son, John, also a catcher, had been drafted in the tenth round by the St. Louis Cardinals, making him the third Dempsey catching prospect to be drafted into the major leagues. In addition to Rick and his son, Rick’s brother Pat had been drafted by Oakland in the second round of the 1977 draft. John played six years in the minors for St. Louis and Kansas City; Pat’s minor-league career lasted 12 seasons with four organizations, including Baltimore. Their sister, Cherie Zaun, had also produced a major league catcher, Gregg, who was drafted by Baltimore in 1989 and spent 16 seasons in the major leagues. (In addition to Rick, Cherie, and Pat, the first of four Dempsey siblings is Tom, who served two tours of duty in Vietnam. The Dempseys’ parents were George T. Dempsey and the former June Archer, who were both vaudeville performers. George also appeared on Broadway in the musical Song of Norway in the late 1940s.)

On October 5, 1991, the Orioles held a weekend ceremony at Memorial Stadium, the site of so many of Dempsey’s grandest moments, to celebrate the closing of the only home they’d known since the franchise relocated to Baltimore from St. Louis in 1954; the following spring the Orioles would move into their new home, Camden Yards. In Milwaukee Dempsey asked the Brewers to allow him to join the festivities in Baltimore, but the club denied his request (he started that day in Boston). So instead, he was on hand in Baltimore the following day for the final game ever played at Memorial Stadium, a 7-1 loss to Detroit played before a crowd of 50,700. After the game Dempsey led the fans in the classic O-R-I-O-L-E-S cheer, spelling out each letter with his body, and then ran the bases in his Babe Ruth imitation.

Dempsey desperately wanted to be a part of the Orioles when they moved into their new home in 1992. “I want to play until I drop,” he confided that winter to Rex Barney, “but I want to be a big league manager.”32 That spring was the first training camp for the team’s new manager, Johnny Oates, and he invited the 42-year-old Dempsey to camp as a nonroster player. Although he competed strongly for the backup role to starter Chris Hoiles, on the final cutdown day the Orioles released Dempsey as a player and offered him a job as coach, which Dempsey declined, still hoping to be picked up by another organization. Without a team to play for, Dempsey was on hand for the Orioles first game at Camden Yards, and he was introduced on the field to a thunderous ovation. He returned briefly to the team’s active list in midseason, and on July 6, against the White Sox at Camden Yards, entered a tie game in the ninth inning, and in the tenth he reached base on a perfectly placed bunt, his 1,093rd and final major-league base hit. At last, Dempsey’s active career was ended.

Dempsey then began his quest for a major-league manager’s job. For three seasons he managed in the Dodgers’ minor-league system, first at Class A Bakersfield, then for two years at Triple-A Albuquerque. Dempsey tried to blend the styles of three legendary managers he had played for, Earl Weaver, Billy Martin, and Tommy Lasorda.

“That’s from one end of the spectrum to another,” he said. “But if I can be as aggressive as Billy, as intelligent as Earl, and as motivating as Tommy, I don’t see how I couldn’t be a good manager in major-league baseball someday.”33 Taking that approach, Dempsey led Albuquerque to the Pacific Coast League title in 1994.

In 1997 Dempsey changed teams. For the next two years he piloted Norfolk, the New York Mets’ Triple-A affiliate, and posted a record of 145-139. He rejoined the Dodgers in 1999 and spent that year and the next as the Dodgers’ bullpen coach.

The 2001 season was Dempsey’s homecoming; he finally returned to Baltimore. In 1997 the man who was generally recognized as the greatest catcher in the franchise’s history had been elected to the Orioles Hall of Fame, and over the next several years Dempsey once again donned the Orioles uniform. First he was a color analyst for the local Comcast SportsNet cable outlet in 2001, then for the next five years filled various coaching roles, alternating among first base, third base, and the bullpen. At least once during those years, Dempsey later revealed, he was offered the manager’s job but the offer, he claimed during his 2008 Crespi Hall of Fame interview, was later rescinded. In 2007 Dempsey moved back into the television booth, as a broadcaster, color analyst, and co-host of the Orioles pre- and postgame shows on MASN, the Orioles’ cable network. As of 2013 he had been a member of the broadcast team for seven years.

Sources

Books

Weaver, Earl, with Berry Stainback, It’s What You Learn After You Know It All That Counts (New York: Doubleday, 1982)

Barney, Rex, with Norman Macht, Rex Barney’s Orioles Memories (Woodbury, Connecticut: Goodwood Press, 1994)

Eisenberg, John, From 33rd Street to Camden Yards (New York: Contemporary Books, 2001)

Boswell, Thomas, Why Time Begins On Opening Day (New York: Doubleday and Company, 1984)

Newspapers

Bemidji (Minnesota) Daily Pioneer

The Capital (Annapolis, Maryland)

Cedar Rapids (Iowa) Gazette

Danville (Virginia) Bee

Des Moines Register

Hayward (California) Daily Review

Huron (South Dakota) Daily Plainsman

Wisconsin State Journal (Madison)

Oneonta (New York) Star

Syracuse Post-Standard

The Sporting News

The Valley News (Van Nuys, California)

Winona (Minnesota) Daily News

Video

http://youtube.com/watch?v=_vjDqjXnRGw

http://ovguide.com/video/rick-dempsey-interview-3-of-3-922ca39ce10036ba0e118fe244bba8f8

Websites

http://baseball-almanac.com

http://baseball-reference.com

http://crespi.org/alumni.htm

http://masnstudios.com/2007/09/orioles-talent

http://patdempsey.com

Notes

1 Thomas Boswell, Why Time Begins On Opening Day, 35.

2 John Eisenberg, From 33rd Street to Camden Yards, 298-99.

3 Dempsey interview at his induction into Crespi High School Hall of Fame.

4 Valley News and Green Sheet, Van Nuys, California, March 17, 1967.

5 Valley News and Green Sheet, May 30, 1967.

6 Earl Weaver, It’s What You Learn After You Know It All That Counts, 27.

7 Rex Barney, Rex Barney’s Orioles Memories, 106.

8 “Seven Mittmen, Yet Twins Eye Another,” The Sporting News, November 30, 1968.

9 Bemidji (Minnesota) Daily Pioneer, October 1, 1969.

10 The Sporting News, June 29, 1974.

11 The Sporting News, June 29, 1974.

12 Eisenberg, 297.

13 The Sporting News, July 3, 1976.

14 Eisenberg, 297.

15 Eisenberg, 297.

16 Eisenberg, 321-22.

17 Barney, 106.

18 Boswell, 35-36.

19 Eisenberg, 297-98.

20 Eisenberg, 297-98.

21 Eisenberg, 297-98.

22 Eisenberg, 297-98.

23 Eisenberg, 297-98.

24 Eisenberg, 297-98.

25 Eisenberg, 297-98.

26 The Sporting News, April 23, 1977.

27 The Sporting News, May 10, 1980.

28 Boswell,.36.

29 Boswell, 36.

30 Weaver, 24.

31 Barney, 107.

32 Barney, 107.

33 Associated Press via The Capital (Annapolis, Maryland), April 10, 1994.

Full Name

John Rikard Dempsey

Born

September 13, 1949 at Fayetteville, TN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.