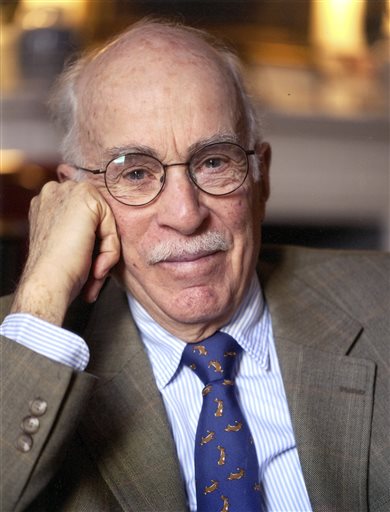

Roger Angell

He is, perhaps, the most exquisitely talented writer ever to focus sustained attention on the subject of baseball. Yet Roger Angell was never a “baseball writer” in the normal sense of the term. Instead, his work on baseball has been an extension of his keen observation and appreciation of the sport as a fan. Moreover, as abiding as his love for baseball has been, it represents just one among many diverse strands of interest and expression that have animated a vigorous and extraordinary—and extraordinarily long—life and career.

He is, perhaps, the most exquisitely talented writer ever to focus sustained attention on the subject of baseball. Yet Roger Angell was never a “baseball writer” in the normal sense of the term. Instead, his work on baseball has been an extension of his keen observation and appreciation of the sport as a fan. Moreover, as abiding as his love for baseball has been, it represents just one among many diverse strands of interest and expression that have animated a vigorous and extraordinary—and extraordinarily long—life and career.

Indeed, if Roger Angell’s story were presented to Roger Angell in fictional form—which could happen because his primary profession has been not writer, but fiction editor—he would be justified in rejecting it for implausibility, for a plot with a bit too much coincidence and permutation, within a setting of decidedly too much elegance and sophistication. As yarns go, this one has been a doozy.

The tale begins on September 19, 1920, in New York City. The household into which Roger (no middle name) Angell was born was far from ordinary. His father, Harvard-educated Ernest Angell, was a Wall Street lawyer who would eventually become the New York regional director of the Securities and Exchange Commission as well as national chairman of the American Civil Liberties Union. His mother, Bryn Mawr-educated Katherine Sergeant Angell, was a writer and editor who would be among the first recruits to The New Yorker magazine following its 1925 founding, and would retain a prominent role there for 35 years.

It was from his father—who’d grown up in Cleveland, and remained a lifelong Indians fan—that young Roger was given a warm introduction to baseball. Writing in 1970, the son quotes the father:

“We had Nap Lajoie at second. You’ve heard of him. A big broad-shouldered fellow, but a beautiful fielder. He was a rough customer. If he didn’t like an umpire’s call, he’d give him a faceful of tobacco juice. The shortstop was Terry Turner – a smaller man and blond. I can still see Lajoie picking up a grounder and wheeling and floating the ball over to Turner. Oh, he was quick on his feet!”1

Ernest wasn’t just a fan, he was a seriously competitive ballplayer far into adulthood, in the local-nine pick-up manner of the era. And, as his son describes it, “my father sailed through Harvard in three years, but failed to attain his greatest goal of making the varsity in baseball, and had to settle for playing on a class team.”2

Angell describes his father:

… lean and tall, with long fingers, brown eyes, and a sense of energy about him. … Handsome and dashing in the flattering, tightly cut suits and jackets of the 1930s (like Gary Cooper, he remained unstuffy in a vest), he strode swiftly, banged doors behind him, and swarmed up stairs, appearing always on the verge of some outdoor errand or expedition. Bravura came naturally to him …

It was this spirit, brought to mountain climbing, to figure skating, to tennis and trout fishing, to skiing and canoeing and gardening and so forth, that sometimes inspired us in the family to call him The King of the Forest.3

And so the never-deskbound “King of the Forest” instilled in his boy a deep avocation for not just baseball—Roger was a pitcher into high school until developing a sore arm—but many other sweaty pursuits, including golf, horseback riding, ice skating, swimming, tennis, and most especially, sailing. Father and son were both raised in circumstances of abundant comfort (if not plain wealth) and both pursued careers of engrossing intellectual challenge, yet both eschewed the ever-available temptation to passively let the flesh soften. This Teddy Roosevelt-style gung ho embrace of the physical realm by an otherwise bookish sort rests at the heart of the perspective of Angell’s first-person-narrative baseball writing.

From his mother Roger Angell inherited his gift for comprehension and mastery of the written word. Moreover, he was afforded the opportunity to essentially replace her at The New Yorker, and sustain a most unique family legacy half a century further. Nevertheless, Angell’s relationship with his mother wasn’t always easy:

Most memories of my mother are affectionate and cheerful, but still center on the bottomless worries and overthoughts that descended on her late in her life. And not always so late, come to think of it.

… For her a fistful of candy never had a chance against the complicated right thing. She loved us all, anxiously and bemusedly, but forgot to hand out kisses because we were great runners or really good-looking or the smartest kid on the block. Stuff like that went without saying, only she never said it.

Nancy Franklin, in a remarkable piece about my mother in The New Yorker in 1995 (she’d never met her), wrote, “It’s funny; as an editor she was maternal but as a mother she was editorial.” This made me laugh, not cry, and it has come to me over time that my own way of loving her was often simply to try to cheer her up.4

Even with formidable advantages, Angell’s childhood knew emotional pain. Ernest and Katharine divorced when Roger was eight:

One explanation for the divorce was that my father, who went to France in 1917 with the A.E.F. [American Expeditionary Force] as a counter-intelligence officer—he spoke French and some German—adopted a Gallic view of marriage and was repeatedly unfaithful to my mother after he came home. Another was that my mother had fallen in love with E. B. White, a colleague of hers at The New Yorker ….

She always insisted that there was no connection between her divorce and their marriage, which came three months after her return from Reno. Whatever. What can be said for sure is that each of my parents grew up with a critically missing parent—she a mother, he a father—and pretty much had to fake it in these roles with their own kids. They worked at this all their lives, though it sometimes pissed you off or broke your heart (choose one) to watch them.5

Following the divorce, young Angell (and his older sister Nancy) lived with their father. But they continued to spend significant time with their mother also, and Angell developed a close relationship with his stepfather E. B. “Andy” White that would last for decades.

White’s primary occupation was editor and writer for The New Yorker, alongside Katharine, but he authored many books as well. He became best known for the highly-acclaimed children’s novels Stuart Little, Charlotte’s Web, and The Trumpet of the Swan, and also co-wrote (with William Strunk Jr.) the writer’s manual The Elements of Style that has been standard issue for college undergraduates since its initial publication in 1959 and four subsequent re-issues.

Angell’s fondness for White was not so much son-to-father (White was seven years younger than Katharine, and ten years younger than Ernest) as nephew-to-uncle:

My mother and Andy White got married in 1929 … and though my sister and I were only weekend and summertime visitors with them after that, I soon felt as much at home at their place—on East Eighth Street and then East Forty-eighth Street, in New York, and then in Maine—as I was with my father the rest of the time.

A fresh household sharpens attention, and one of the things I picked up was that sense of ease and play that Andy brought to his undertakings. Though subject to nerves, he possessed something like that invisible extra beat of time that great athletes show on the field. Dogs and children were easy for him because he approached them as a participant instead of a winner.6

As a teenager Angell was boarded at the elite Pomfret School in Connecticut. His summers were actively busy, often involving ambitious vacations arranged by his father:

I was a New York City kid who knew the subways and museums and movie theaters and ballparks by heart, but in the 1930s also got out of town a lot, mostly by car. I drove (well, was driven) to Bear Mountain and Atlantic City and Gettysburg and Niagara Falls; went repeatedly to Boston and New Hampshire and Maine; drove to a Missouri cattle farm owned by an uncle; drove there during another summer and thence onward to Santa Fe and Tesuque and out to the Arizona Painted Desert. Then back again, to New York.

Before this, in March 1933—it was the week of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s first inaugural—I’d boarded a Greyhound bus to Detroit, along with a Columbia student named Tex Goldschmidt, where we picked up a test-model Terraplane sedan at the factory (courtesy of an advertising friend of my father’s who handled the Hudson-Essex account) and drove it back home. A couple of months later, in company with a math teacher named Mrs. Burchell or Burkhill and four Lincoln School seventh-grade classmates, I climbed into a buckety old Buick sedan and drove to the Century of Progress Exposition in Chicago; we came back by way of Niagara Falls …. 7

Following graduation from Pomfret in 1938, Angell followed his father’s path and attended Harvard. In June 1942 he graduated with a Bachelor’s degree in English. Barely a month later, with World War II in full flame, Angell was drafted into the U.S. Army Air Force.

He undertook basic training in Atlantic City, then was troop-trained to Lowry Field, outside Denver, for armament school. After further training, he served a long stint at Lowry as a machine gun instructor. In early 1944 Angell was transferred to a Public Relations post in Honolulu, where he became the managing editor of Brief, a weekly magazine distributed to American service members throughout the Pacific theatre. He never saw combat. In his autobiography Angell presents a long list of friends and acquaintances who lost their lives to World War II, and he assesses that he had “not been in the war exactly, but like others back then I’d got the idea of it.”8

While stationed at Lowry Field in October 1942, Angell married Evelyn Baker, who’d been his girlfriend throughout his college years. She was “thin and brown-haired, with a strong chin,” and “tougher than anyone [he]’d met before.”9 They would remain married for more than 20 years, and had two daughters, Caroline (“Callie”) and Alice.

At the conclusion of the war, Angell “observed Christmas of 1945 on the homeward-bound carrier Saratoga, converted to a transport.”10 He was 25 years old, and ready to begin his career.

No suggestion exists that Angell had any ambition other than to be a writer. He and Evelyn “swiftly acquired New York jobs and friends, an apartment in the upper reaches of Riverside Drive, a two-tone Ford Tudor, a bulldog, and … a baby daughter…. The works.”11 He spent his first post-war year avidly contributing to whatever publication would accept his pieces. In 1947 Angell landed his first serious job, with Holiday magazine, an upscale new travel periodical. He would become senior editor, and remain there for nearly a decade.

The Holiday gig provided Angell with not just interesting work and a budding income, but the sort of experience that simply couldn’t be found elsewhere. In his autobiography Angell recounts a particular six-week 1949 business trip to Europe, crossing the Atlantic aboard the French liner De Grasse, in which he and Evelyn rubbed elbows with actor Alfonso Bedoya (who sneered “We don’t need no badges” in The Treasure of the Sierra Madre), with playwright Tennessee Williams, and with novelist Somerset Maugham (at his opulent Villa Mauresque estate in Cap Ferrat in southeastern France).12 Angell was doing just fine.

But in 1956 Angell would take employment with The New Yorker, the job he was perhaps destined to have, and the one he would hold for the rest of his life.

Angell was a perfect fit for The New Yorker, not just because of his boundless ability as a writer and editor, and, of course, his matchless pedigree, but for his breadth of interest and curiosity. As a writer, he contributed a variety of stories, casuals, “Notes and Comments” pieces, movie reviews, and for many years the magazine’s annual Christmas verse under the heading of, “Greetings, Friends!” Within the topic of sports alone, in addition to his baseball pieces, Angell wrote about tennis, hockey, football, rowing, and horse racing. As a fiction editor, among his stable of regular writers were John Updike, William Trevor, and Woody Allen.13

The idea of Angell chronicling baseball for the magazine was not his, but came from editor-in-chief William Shawn (the father of playwright and actor Wallace Shawn). As Angell explained, “Our magazine is in the enviable position of ‘covering’ only those things which appeal to specific writers and editors.”14 Shawn sent Angell to Florida in early 1962 with the task of delivering a piece about Spring Training, and the April 7, 1962, issue of The New Yorker included Angell’s “The Old Folks Behind Home,” a leisurely observation of exhibition games from the perspective of elderly retired fans.

This initial piece was well received, but there was no strategic plan for Angell to contribute baseball articles on a regular basis. “I just kept going,” Angell explained. “I had no idea it would go on this long…. I just went on from year to year because I always found something else I wanted to write about. It seemed to be a good fit.”15

Angell soon settled in to a pattern of contributing two or three baseball pieces a year. He deliberately made no attempt to formally “cover” the sport in the manner of The Sporting News or Sports Illustrated, but instead maintained the perspective of a fan. His vantage point was typically a seat in the grandstand rather than the press box, and he was as likely to focus on fellow spectators and the ballpark experience as the athletes and action on the field. A good example is his consideration of attending a New York Mets game at the Polo Grounds in the summer of 1963, in that antique ballpark’s final season:

The dirt, the noise, the chatter, the bursting life of the Met grandstands are as rich and deplorable and heart-warming as Rivington Street. The Polo Grounds, which is in the last few months of its disreputable life, is a vast assemblage of front stoops and rusty fire escapes. On a hot summer evening, everyone around here is touching someone else; there are no strangers, no one is private. The air is alive with shouts, gossip, flying rubbish.

Old-timers know and love every corner of the crazy, crowded, proud old neighborhood. The last-row walkup flats in the outer-most lower grandstands, where one must peer through girders and pigeon nests for a glimpse of green; the little protruding step at the foot of each aisle in the upper deck that trips up the unwary beer-balancer on his way back to his seat; the outfield bullpens, each with its slanting shanty roof, beneath which the relief pitchers sit motionless, with their arms folded and their legs extended; and the good box seats, just on the curve of the upper deck in short right and short left: front windows on the street, where one can watch the arching fall of a weak fly ball and know in advance, like one who sees a street accident in the making, that it will collide with that ridiculous, dangerous upper tier for another home run.

Next year, or perhaps late this summer, all this will vanish. The Mets are moving up in the world, heading toward the suburbs. Their new home, Shea Stadium, in Flushing Meadow Park, will be cleaner and airier: a better place for the children.

Most of the people there will travel by car rather than by subway; the commute will be long, but the residents will be more respectable. There will be broad ramps, no crowding, more privacy. All the accommodations will be desirable: close to the shopping centers, and set in perfect, identical curves, with equally good views of the neat lawns. Indeed, a man who leaves his place will have to make an effort to remember exactly where it is, so he won’t get mixed up on his way back and forget where he lives.

It will be several years, probably, before the members of the family, older and heavier and at last sure of their place in the world, indulge themselves in some moments of foolish reminiscence: “Funny, I was thinking of the old place today. Remember how jammed we used to be back there? Remember how hot and noisy it was? I wouldn’t move back there for anything, and anyway it’s all torn down now, but, you know, we sure were happy in those days.”16

Angell’s baseball pieces in The New Yorker were a hit, and they became the channel through which he gained fame. In 1972, the first ten years of these articles were collected and published as The Summer Game. The book was critically acclaimed and an immediate bestseller. The notice in The New York Times Book Review could hardly be more laudatory: “Page for page, The Summer Game contains not only the classiest but also the most resourceful baseball writing I have ever read.”17

As the decades flowed, so did Angell’s quietly perceptive and finely wrought baseball impressions in The New Yorker. They continued to be collected and retrospectively presented in book form, to sustained market appetite as well as critical praise: Five Seasons: A Baseball Companion (1977), Late Innings: A Baseball Companion (1982), Season Ticket: A Baseball Companion (1988), Once More Around the Park: A Baseball Reader (1991), and finally a “greatest hits” version, Game Time: A Baseball Companion (2003).

In a break from the formula, at the age of 80 Angell wrote A Pitcher’s Story, a book-length study of star pitcher David Cone that is also a thorough examination of the art and challenge of pitching in general.

Altogether Angell’s body of work is quite unlike any other. As Steven P. Gietschier of The Sporting News put it:

Angell is that rare baseball fan who has been able to make a career out of his pleasure. Without abandoning the wonder, the affection, and the detachment that characterize a fan’s kinship to baseball, Angell has fashioned a string of remarkable essays that explore the sport in consistently new ways. His work possesses a grace and elegance previously unknown in sports journalism and has earned a lasting place in the literature spawned by the national pastime.18

Angell was prominently featured among the sage on-camera interviewees in Ken Burns’s 1994 documentary film Baseball. In 2011 Angell was named as the inaugural recipient of the PEN/ESPN Lifetime Achievement Award for Literary Sports Writing, and in 2013 he received the J.G. Taylor Spink Award from the Baseball Writers Association of America, the baseball writers’ equivalent of the Hall of Fame. He is the first non-newspaper writer, and the first non-Baseball Writers Association of America member, to win the Spink Award, which is voted upon by the BBWAA membership.

In February of 2014, The New Yorker published “This Old Man,” Angell’s pondering on the implications of his being still alive at 93. With neither self-pity nor boastfulness—instead, with wry humor—Angell opens with a presentation of a long list of old-guy ailments (arthritis, macular degeneration, shingles, a heart condition, knee trouble, a herniated disk), before assessing:

I’ve endured a few knocks but missed worse. I know how lucky I am, and secretly tap wood, greet the day, and grab a sneaky pleasure from my survival at long odds. The pains and insults are bearable. My conversation may be full of holes and pauses, but I’ve learned to dispatch a private Apache scout ahead into the next sentence, the one coming up, to see if there are any vacant names or verbs in the landscape up there. If he sends back a warning, I’ll pause meaningfully, duh, until something else comes to mind.

… Decline and disaster impend, but my thoughts don’t linger there. It shouldn’t surprise me if at this time next week I’m surrounded by family, gathered on short notice—they’re sad and shocked but also a little pissed off to be here—to help decide, after what’s happened, what’s to be done with me now. It must be this hovering knowledge, that two-ton safe swaying on a frayed rope just over my head, that makes everyone so glad to see me again. “How great you’re looking! Wow, tell me your secret!” they kindly cry when they happen upon me crossing the street or exiting a dinghy or departing an X-ray room, when the little balloon over their heads reads, “Holy shit—he’s still vertical!”19

Though the mood of the piece retains this spunky attitude, Angell devotes much of it to the subject of personal loss, that booby prize awarded to those who outlive their peers: “the downside of great age is the room it provides for rotten news”.20 Like that of his parents, Angell’s first marriage ended in divorce, but a half-century following the breakup Angell here still mentions Evelyn (who passed away long ago), and with warmth. He writes at vivid length about his second wife, Carol Rogge (whom Angell married in 1963; together they had a son, John Henry), who passed away in 2012 at the age of 73, and most achingly he writes about his late daughter Callie, who committed suicide in 2010 at the age of 62.

With the authentic wisdom available only to the very, very old, what Angell writes about most in “This Old Man” is coping: getting by, if not overcoming, difficulty and pain and heartbreak and sorrow. Being Angell, he devotes attention to the many things he loves, including dogs and family and friends and reading and Scotch whisky and (yes) baseball and music and movies and jokes. He also devotes cheerful attention to the subject of sex, and in this undertaking his familiar delicate touch has never been more finely exhibited.

The article concludes, indeed, with an affirmation of the ever-invigorating power of the matters of the heart:

Getting old is the second-biggest surprise of my life, but the first, by a mile, is our unceasing need for deep attachment and intimate love. We oldies yearn daily and hourly for conversation and a renewed domesticity, for company at the movies or while visiting a museum, for someone close by in the car when coming home at night.

… I believe that everyone in the world wants to be with someone else tonight, together in the dark, with the sweet warmth of a hip or a foot or a bare expanse of shoulder within reach. Those of us who have lost that, whatever our age, never lose the longing: just look at our faces. If it returns, we seize upon it avidly, stunned and altered again.21

Well into his tenth decade, Roger Angell’s writing continues with burningly profound candor. His latest offering (last? we’ll see if that safe drops) is just the latest in a very, very long line of essays that set a towering standard, whether the subject is the sport we love, or the people we love most deeply.

Published May 15, 2014

Postscript

Roger Angell died at the age of 101 on May 20, 2022.

Notes

1 Roger Angell, “Baseball in the Mind,” in This Great Game, edited by Doris Townsend (Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, 1971), p. 26

2 Angell, Let Me Finish (Orlando: Harcourt, 2006), p. 75

3 Ibid, p. 30-31

4 Ibid, pp. 269-270

5 Ibid, pp. 289-290

6 Ibid, p. 120

7 Ibid, pp. 8-9

8 Ibid, p. 193

9 Ibid, p. 175

10 Ibid, p. 192

11 Ibid, p. 205

12 Ibid, pp. 194-210

13 http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/bios/roger_angell, accessed 19 April 2014

14 Michael Mok, “Roger Angell,” Publishers Weekly, 202 (10 July 1972), p. 22

15 Jared Haynes, “An Interview with Roger Angell: They Look Easy, But They’re Hard,” Writing on the Edge, 4 (Fall 1992), pp. 133-150

16 Angell, “S is for So Lovable,” The Summer Game (New York: Popular Library, 1972), pp. 66-67

17 Ted Solotaroff, The New York Times Book Review (11 June 1972)

18 Steven P. Gietschier, “Roger Angell,” Dictionary of Literary Biography, 171 (1996), p. 11

19 Angell, “This Old Man,” The New Yorker (17 & 24 February 2014), p. 61

20 Ibid, p. 61

21 Ibid, p. 65

Full Name

Roger Angell

Born

September 19, 1920 at New York, NY (US)

Died

May 20, 2022 at New York, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.