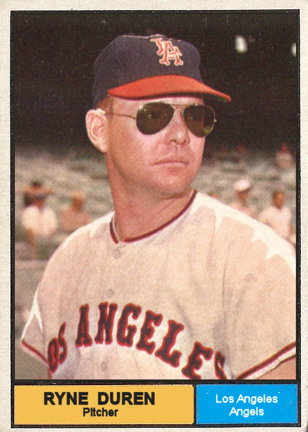

Ryne Duren

With his poor eyesight, and notoriously poor control, flame-throwing pitcher Ryne Duren’s fastball put the fear of God into opposing hitters in the late 1950s and early 1960s. “Duren was the standard by how we ranked hard throwers,” All-Star pitcher and pitching coach Jim Kaat said. “We’d say [so-and-so] can throw almost as hard as Duren.”1

With his poor eyesight, and notoriously poor control, flame-throwing pitcher Ryne Duren’s fastball put the fear of God into opposing hitters in the late 1950s and early 1960s. “Duren was the standard by how we ranked hard throwers,” All-Star pitcher and pitching coach Jim Kaat said. “We’d say [so-and-so] can throw almost as hard as Duren.”1

Duren labored as a starting pitcher in the minor leagues for the first eight years of his career but it was not until he was converted to a relief pitcher, and was brought up to the Major Leagues by the New York Yankees that his career really took off. He drew national attention by throwing 100-miles-per-hour while wearing tinted sunglasses with lenses as thick as the bottoms of Coca-Cola bottles.

Duren mastered his control problems enough to be selected to the AL All-Star team in 1958, 1959, and 1961. His speed and his control issues were perhaps only exceeded by his fondness for drink, and his career was likely shortened by the effects of alcoholism. “I never really knew what it was like to pitch a sober inning,” Duren admitted years later.2 After his playing days, he became a nationally respected addiction counselor and with Tom Sabellico authored a book about his battles with alcoholism entitled, “I Can See Clearly Now.”3

Rinold George Duren, the third of eight children born to Rinold and Anne Duren, was born on February 22, 1929 in Cazenovia, a small town in south-central Wisconsin. His father served as town postmaster and his mother as assistant postmaster, while Ryne worked on the family farm tending animals, and planting crops. He also worked in feed mills, which he claimed helped to develop his arm muscles. At age fourteen he tried out for the Cazenovia High School baseball team, but during pitching tryouts he was very wild and injured a teammate which resulted in his being moved to second base and the outfield. Ryne’s true passion for baseball was ignited in the spring of 1945 when he came down with a severe case of rheumatic fever. The illness which caused his vision problems confined him to bed for almost six months where he began listening to Cubs games on WGN radio and followed the team through their World Series appearance. He was hooked on baseball.

His unspectacular high school baseball career over, Ryne began working in a factory in Beloit, but returned to Cazenovia on weekends to play sandlot baseball for the Cazenovia Reds in 1948. Given a chance to pitch, he led his team to the Sauk County title. “I could throw so hard that I’d strike out 21-23 batters a game and went through 33 consecutive no-hit innings,” he said.4 Ernie Randolf, a bird dog scout for the St. Louis Browns, witnessed Duren’s exploits and Browns’ scout Eddie Dancisak ultimately signed Ryne in January 1949 for a $500 bonus and $300 per month salary.

With the unwavering support of his wife, Beverly (nee Collins) whom he married in December 1948, Ryne began his professional baseball career with the Wausau (WI) Lumberjacks in the Class D Wisconsin State League.5 “The combination of my eyesight and the poorly lighted minor league ballparks made it very difficult for me to see the catcher’s signs,” Duren said about surrendering 114 bases on balls in 85 innings.6 The Browns sent him to St. Louis to see an eye specialist who advised Duren to give up baseball. “I was not going to let my vision stand in the way of my dream,” said Ryne, who was diagnosed with myopia (nearsightedness). 20/70 vision in his left eye and 20/200 vision in his right eye (the definition of legal blindness is vision that cannot be corrected to better than 20/200 in your best eye), poor depth perception, and an acute sensitivity to light.7 He began wearing thick “Coke–bottle lens” glasses and tinted sunglasses which later became a “trademark” of his in the Major Leagues.

After winning 15 games for the Pine Bluff (AR) Judges in the Class C Cotton States League in 1950, Duren was promoted to the Dayton Indians in the Class A Central League where he won a career-high seventeen games in 1951 and led the league with 238 strikeouts in only 198 innings. 8 “It wasn’t until I got into professional baseball that I became aware of what poor control I had,” said Ryne who also walked 194 batters. Billed as one of the Browns’ top prospects, Duren played winter ball for Navegantes del Magallanes (Magellan’s Navigators) based in Valencia in the Venezuelan League to hone his control. “I had never seen a big-league game,” said Ryne about this point in his career. “I didn’t know if I had talent or not.”9

The Browns promoted Ryne to the San Antonio Missions in the Texas League (Double A) to start the 1952 season where he averaged almost one walk per inning, so he was demoted to the Anderson (SC) Rebels in the Class B Tri-State League. After a record-breaking performance against the Asheville Tourists in which he struck out 17 batters through the first nine innings and held the opposition hitless through eleven innings before he lost, 1-0 in the twelfth, Ryne was promoted to the Scranton (PA) Miners in the Class A Eastern League.

Back in San Antonio in 1953, Ryne led the league with 212 strikeouts, posted a 2.63 ERA and won 12 games (including a 7-inning no-hitter). Browns’ vice president Bill DeWitt labeled Duren the team’s top prospect and placed him on the major league roster. After playing for Willard in the Colombian winter league, Ryne participated in his first major league spring training in 1954 for the new Baltimore Orioles. Plagued by wildness and inconsistency, the 25-year old Duren was sent back to San Antonio where he struck out 224 batters in 220 innings, but walked 144. He was recalled to the parent club in September, but broke a bone in his pitching hand which delayed his major league debut until the last game of the season, in which he pitched two innings of relief against the White Sox and gave up three runs (two earned) and struck out Minnie Minoso and Willard Marshall. He didn’t make it back to the majors for almost three more years.

“Everybody had a gimmick to help me gain control,” Duren said about his wildness.10 At the Orioles spring training camp in 1955, manager Paul Richards ordered him to become a breaking ball pitcher. “I started to throw curves and sliders,” Duren said, and “The result was a sore arm.”11 Duren split his time with the Seattle Rainiers in the Pacific Coast League and San Antonio, but was limited by soreness the entire year, and tossed less than 90 innings. Ryne had a lot of potential, but frustrated his managers. “[They] saw my wildness and my misbehaving and would get angry at me. They said, ‘You dumb son of a bitch, with talent like yours, you should be in the big leagues winning 20 games a year,’” said Duren.12

After Duren’s third spring training with the Orioles in 1956, Richards gave up on him and optioned him outright to the Vancouver Mounties in the PCL. There, he came under the tutelage of Lefty O’Doul who, according to Ryne, was the first manager who attempted to teach him how to pitch. Ryne learned how to “move the ball” and pitch to different locations. “I want you to develop a sense of touch, so that you can tell when you’re not throwing right.”13 He responded to O’Doul’s fatherly mentoring and walked just 87 in 205 innings, and won eleven games. “[O’Doul] helped me develop enough control so that I could pitch in the majors,” said Ryne. “Lefty taught me how to win.”14 Unimpressed, Richards traded Duren to the Kansas City Athletics in September as part of a multi-player deal.

Playing for Lou Boudreau’s A’s, the 6-foot-2, 190-pound Duren made his first major league start on May 2 against the Yankees and pitched seven innings of six-hit ball while striking out eight, and driving in the A’s only run on a drag bunt in a 3-1 loss. After the game Hank Bauer and Gil McDougald commented that Duren “threw too hard for married men to hit”. Duren’s reputation as the hardest-throwing and most-dangerous pitcher in the major leagues was born; however, inconsistency and a lack of control were his nemeses. After six starts and two relief appearances, he was 0-3 with a 4.41 ERA. He was shifted to the bullpen and struggled. At the June 15 trading deadline, the A’s shipped Duren and two others to the Yankees in the deal which brought Billy Martin, fresh off the brouhaha and scandal at the Copacabana in New York, and Ralph Terry to the team. “Boudreau told me that he hadn’t wanted the trade,” recalled Duren, “because he considered me the best pitcher on the team.”15

The Yankees assigned Duren to their Triple-A affiliate in the American Association, the Denver Bears, managed by Ralph Houk. In his first start, Duren tossed a seven-inning no-hitter against the Louisville Colonels on his way to a 13-2 record in just over two months. Duren’s personal success and the team’s (they won the Junior World Series title over the Buffalo Bisons) overshadowed his alcoholism and increasingly rowdy and belligerent behavior while drunk. Houk had to bail out Duren and teammate Norm Siebern from jail in Louisville when both were arrested in July after a brawl with locals and charged with disorderly conduct and resisting arrest. In the melee, Duren was hit with a blackjack and required 22 stitches in his head. Recognizing that Duren survived with his fastball and possessed just an average slider and curve, Houk was the first manger to suggest that Duren be used as a “fireman”, as relievers were referred to in that era. Houk urged Casey Stengel to call him to up in September, but the Yankees already had Bob Grim in the bullpen and had acquired 40-year-old Sal Maglie on September 1.

“I had to work my ass off and watched my behavior”, Duren said about his first spring training with the Yankees in 1958, “because the Yankees were still reluctant to bring me up.”16 Duren earned Stengel’s confidence and made the team, and in his first full year in the major leagues put together one of the most memorable seasons for a reliever in history. In the first two months of the season, Duren saved seven games and amazed fans and sportswriters with his strikeouts prompting The Sporting News to announce that “Duren is the pitching find of the year. He throws harder than any hurler in the league.”17 He finished the season with a league-high 20 saves in just 44 games, struck out 87 batters in 75 2/3 innings and limited hitters to a .157 batting average. He made his first of three All-Stars teams (though he did not pitch in the 1958 game), and was named the American League Rookie Pitcher of the Year by The Sporting News.

Duren’s impact on baseball in 1958 cannot be measured by statistics alone. Baseball had never seen someone like Duren before: A hard-throwing fastball pitcher with thick glasses and poor control who often squinted on the mound to decipher the catcher’s signs. Duren and the Yankees cultivated the “dangerous” side of his pitching. “There was no doubt that batters were scared of me especially on days when I was throwing my best,” said Duren.18 He preferred the mound to be sloped in order to achieve the maximum downward velocity on his pitches. While warming up one day, he threw the ball wildly and it sailed over the head of his catcher and to the screen. “The fans got a big kick out of it and the sportswriters played it up,” Duren remembered. “So now and then I’d throw my first warm-up pitch onto the screen. [Coach] Frank Crosetti encouraged me to do it because he said it put a little extra fear in the opponents.”19 Duren’s wildness took on a life of its own. When Jimmy Piersall was on-deck studying his pitches, Duren purposely threw at him knocking him down; thus another degree of wildness, one that endangered even the on-deck batter was born. Undeservedly, Ryne developed a reputation as a “head hunter” and was sometimes the target of opposing pitchers when he batted. On July 24 he suffered a concussion when he was beaned in the head by Detroit’s Paul Foytak and was carried off the field on a stretcher.20

Duren was the most talked about reliever in the game and not always because of mound exploits. In the train car to New York after the Yankees clinched the AL pennant on September 14 in Kansas City, Duren got into an altercation with coach Houk (who joined the Yankees staff in 1958) and shoved Houk’s cigar in his face. “[Houk] swung his hand at me and struck me pretty good with one of his World Series rings and cut my head. I was too drunk to remember what happened.” Duren said of the melee which Leonard Schechter, a New York sportswriter, made into national headlines.

In the Yankees’ World Series triumph, Duren made three appearances, each lasting at least two innings and had a record of 1-1. After earning a save in Game Three, he pitched 4 2/3 innings in Game 6 and struck out eight batters; however, a “choke gesture” that he made to home plate umpire Charlie Berry garnered more publicity than his fourteen strikeouts and 1.93 ERA in 9 1/3 innings in the Series. Duren was subsequently fined $250 by commissioner Ford Frick. After the season, Dan Daniel of the New York World-Telegram called Duren “the most exciting player” in baseball, and said that “Duren’s every throw was watched with the keenest of interest, almost bated breath. He also received votes for the AL MVP for the only time in his career.”21

Duren recuperated from off-season knee surgery at his home in San Antonio with his wife and son, Steve. After two rough outings to begin the 1959 season, Duren hit stride. He made 17 consecutive appearances, from May 10 through July 14, without giving up a run, a stretch of 31 1/3 scoreless innings, and another 3 innings in his second All-Star game when he struck out four batters, including Willie Mays and Eddie Mathews. With age creeping up on the Yankees they struggled, hovering around .500 for most of the season and finished a distant 3rd at 79-75. On September 13 a Tito Francona liner struck Duren on the right shin. He was carried from the field, but x-rays showed no broken bone. Duren’s season ended abruptly on September 19 when he fell at Yankee Stadium and broke a bone in his wrist. Despite his second extraordinary season (96 strikeouts in 76.2 innings, 14 saves, and a career-low 1.88 ERA) general manager George Weiss was not impressed.22 “Players just despised Weiss,” Duren said. “He was cheap and aloof. We felt exploited and frustrated.” When he sent Duren a contract calling for a 25% salary cut, from $16,000 to $12,000, Duren refused to sign it.

With a new contract and salary increase, the 31-year old Duren reported to the Yankees spring training in St. Petersburg after an off-season operation to repair his wrist, but was bothered by pain in his knee. After five consecutive scoreless appearances to start the season, Ryne was beset with control problems and inconsistent performances. He lost his job as closer in June to Bobby Shantz. The 1960 season was a turning point in Duren’s career. Depressed by his pitching performances, he started drinking more and saw his life careening out of control. With increasingly erratic and dangerous behavior, Ryne scared and alienated his teammates. “Performance was the permission to do what we wanted,” Duren said; however, management chose not to turn a blind eye to the drinking habits of an inconsistent reliever. “There were little innuendos in the press about my drinking,” Duren remembered. “But the sportswriters had loyalty toward me because we’d go drinking together. We all thought drinking was part of a ballplayer’s social life.”23

In his second World Series in three years, Duren made two appearances, giving up just one run and striking out five in four innings, but was overlooked with the title on the line in Game Seven. In the pivotal 8th inning with the Yankees leading 7-5, Stengel sent in Jim Coates to relieve Shantz. “I always regret that they didn’t have me in the game, because I thought I was a better pitcher at that point than Coates.”24 After giving up an RBI-single to Roberto Clemente by failing to cover first base in time, Coates surrendered Hal Smith’s dramatic three-run home run to give the Pirates a 9-7 lead. “I only made one mistake in baseball,” Duren remembered Stengel telling him after the World Series loss, “and that was bringing in the other guy when I should have brought you in.”25

Wholesale changes ensued after the Yankees lost the Series. When Houk was named the new skipper, rumors swirled that Duren would be traded. Houk, a former marine, wanted to instill discipline and change the attitude in the clubhouse. “Duren can’t drink,” Houk said. “He’s a Jekyll and Hyde.”26 When Duren received Houk’s first fine in spring training for behavior “detrimental to the team,” he landed in the manager’s doghouse .27 Houk named 21-year old Bill Stafford his primary closer which made Duren expendable. After just four appearances Ryne was traded to the expansion Los Angeles Angels on May 8 as part of a five-player deal.

Wholesale changes ensued after the Yankees lost the Series. When Houk was named the new skipper, rumors swirled that Duren would be traded. Houk, a former marine, wanted to instill discipline and change the attitude in the clubhouse. “Duren can’t drink,” Houk said. “He’s a Jekyll and Hyde.”26 When Duren received Houk’s first fine in spring training for behavior “detrimental to the team,” he landed in the manager’s doghouse .27 Houk named 21-year old Bill Stafford his primary closer which made Duren expendable. After just four appearances Ryne was traded to the expansion Los Angeles Angels on May 8 as part of a five-player deal.

Removed from the pressure of New York, Duren joined a relaxed Angels team managed by Bill Rigney and roomed with pitcher Art Fowler. In his Angels’ debut on May 10, Ryne fanned 5 Red Sox; eight days later he struck out four batters in one inning against the White Sox when catcher Del Rice gave up a passed ball. With the Angels’ thin starting rotation, Rigney experimented with Duren as a starter. Given his first start on June 9 against Boston, Duren established an AL record by striking out seven consecutive hitters on his way to eleven strikeouts in 6 2/3 innings. It was his first victory as a starter in the major leagues. On June 28 against the Yankees he pitched his most memorable game of the season and one which Joe King of the World-Telegram called “the greatest game in the ‘greatest’ town in the brief history of the Angels.”28 With his typical stiff, Frankenstein-like maneuvering and manners on the mound, Duren struck out a career-high 12 batters in eight innings and earned the win in a three-hit victory, 5-3. His strikeouts against the free-swinging Yankees may have been expected, but his two-out single off Bob Turley in the 6th inning, knocking in Ted Kluszewski and Joe Koppe was his first hit in three years. (Duren batted just .061 in his career (7-for-114).

Duren’s fleeting moments of brilliance were tempered by his maddening inconsistency. In San Francisco as the lone Angel representative for his third All-Star game in four years despite a 4.98 ERA, Duren met another tragedy when he learned that his two-week old infant son Craig had died. “The loss of Craig, the drinking, the fighting with Beverly, the cross-country trade, all of it got to be too much,” said Duren.29 His pitching woes in the second-half of the season were interrupted by his first and only career shutout when he tossed a three-hitter against the Indians. He finished the season with career-highs in innings pitched (104) and strikeouts (115); however, his 6-13 record and 5.19 ERA underscored his struggles on the mound. “I was feeling beat and tired,” Duren said about the end of the season and landed in Inglewood Hospital in California, officially diagnosed with pneumonia but suffering from the acute effects of alcoholism.30

Leaving the friendly confines of Wrigley Field, with its seating capacity of less than 21,000, in south Los Angeles, the Angels played in Dodger Stadium in 1962 and surprised baseball with their 3rd-place finish. “The role of the relief pitcher has changed and relief pitchers have been getting more credit,” said Duren prior to reporting to spring training. Rigney employed a closer-by-committee approach to the season in which eight different pitchers finished at least 12 games. It was feast or famine with Duren: he surrendered 10 runs in three games without recording an out; and two runs in another two games with just one out recorded in each. In his other 37 appearances his ERA was under 3.00.

The 34-year-old Duren reported to the Angels’ spring training in 1963 sober for six weeks, and “trying desperately to hold on to my career, my marriage, my life.”31 Duren was still in possession of his fastball, but he couldn’t pitch as often and couldn’t warm up as quickly as he used to. The Angels placed him on waivers during spring training, but after he went unclaimed, they sold him to the Philadelphia Phillies. “Leaving the Angels was a very difficult thing to do,” Duren said. “Unlike the feeling of relief I sensed upon leaving the Yankees, this trade left me feeling empty and sad.”32 Staying sober for the season, Duren responded with his most effective year since 1959. Pitching better as the season progressed, Duren was pressed into the starting rotation in mid-June and won his first start in the National League when he beat the Reds by pitching six strong innings. He won two of his next four starts, including his last professional complete game victory by holding the Pirates to one run (a home run by Roberto Clemente) and striking out seven in the second game of a double header on July 4. He finished the season at 6-2 with 84 strikeouts in 87 1/3 innings and a 3.30 ERA.

In his first season with the Phillies, Duren had begun throwing more off-speed pitches to set up his fastball. Manager Gene Mauch wanted a rubber-armed power pitcher to set up closer Jack Baldschun and acquired dependable Ed Roebuck from the Washington Senators in mid-April, 1964 making Duren expendable. Traded to the Reds, Duren was reunited with manager Fred Hutchinson who coached him briefly in Seattle in 1955. “The Reds were the rowdiest bunch I played with,” Duren admitted.33 In a dramatic and traumatic year for the Reds, “Hutch” was dying of cancer and resigned after 109 games. In mid-September, as the Phillies commenced their “Phold,” the Reds won 12-of-13 games to go from 8 1/2 games down to 1 game up in the NL. With just two appearances in September, Duren was the odd-man out in the bullpen despite his 2.89 ERA for the Reds.

Duren’s final, chaotic season in professional baseball was 1965. Released outright by the Reds due to alcohol-related incidents, including knocking down Pete Rose’s door in a drunken stupor and being arrested for driving while intoxicated, Duren was acquired by the Phillies. However, it was clear that after an alcohol-free summer in 1963, two years of heavy drinking had eroded his skills. “It was quickly obvious to Gene that I would be of no use to the Phillies,” Duren said.34 Released after just six appearances, Duren was lucky to find a spot with the Washington Senators, managed by Gil Hodges. “I put Gil through hell,” Duren recalled.35 With a 6.65 ERA with the Senators, Duren’s career came to an abrupt end. After surrendering two runs to the White Sox in Washington in his swan song on August 18 without registering an out, Duren attempted suicide. “I don’t really remember leaving the hotel and climbing the nearest bridge, threatening to jump and end it all” Duren said.36 Hodges showed up in a police car and talked him down from the bridge. A week later, Duren was released. He finished his career with a 27-44 record, 57 saves, and a 3.83 ERA in 589 1/3 innings; he also struck out 630 batters and walked 392. He won 95 games in his minor league career.

Without baseball, Duren’s life took a drastic turn in the off-season. His wife filed for divorce after he almost burned down their house while smoking in bed after a day of drinking. Having squandered all of his money from his playing days, he worked a series of odd jobs from gas station attendant to dishwasher. He landed in a flophouse, and was then committed to the Texas State Mental Hospital less than six months after his last game with the Senators. Released, but unable to break the spell alcohol cast over him, Duren moved to Wisconsin where he continued to struggle. After another suicide attempt, he entered DePaul Hospital in Milwaukee where he underwent twenty-two-months of treatment and miraculously turned his life around.

From 1968 until his death in 2011, Duren served as an addiction counselor for numerous agencies, foundations, and hospitals where he worked with adolescents and adults and taught them about the dangers of alcohol from his own personal and tragic perspective. After his rehabilitation, Duren remained close to baseball, participated regularly in old-timers games and reunions, and spoke with players about the seduction of alcohol and the pressures of the sport.

Duren captured the attention of the baseball world for a while, and spent the latter half of his life atoning for his excesses. He died at the age of 81 on January 6, 2011, at his winter home in Lake Wales, Florida. For a pitcher with only twenty seven major league victories, Duren created many headlines. “Ryne could throw the heck out of the ball,” Yogi Berra said upon hearing of Ryne’s death. “He threw fear in some hitters. I remember he had several pair of glasses, but it didn’t seem like he saw good in any of them.”37

This biography is included in the book “The Year of the Blue Snow: The 1964 Philadelphia Phillies” (SABR, 2013), edited by Mel Marmer and Bill Nowlin. For more information or to purchase the book in e-book or paperback form, click here.

Notes

1 Ryne Duren with Tom Sabellico, I Can See Clearly Now. Chula Vista, CA: Aventine, 2003, 250.

2 ibid.

3 The Sporting News, May 6, 1978, 34.

4 Danny Peary, ed. We Played the Game. New York: Black Dog and Leaventhal, 1994, 100.

5 All minor and major league statistics have been verified on Baseball-Reference.com; www.baseballreference.com.

6 Duren 54.

7 ibid.

8 Peary, 273.

9 Duren, 63.

10 Peary, 273.

11 Peary, 307.

12 Peary 273.

13 Peary, 342.

14 ibid.

15 Peary, 370.

16 Peary, 430.

17 The Sporting News, May 28, 1958, 7.

18 Peary, 420.

19 Peary, 420.

20 The Sporting News, August 6, 1958, 7.

21 The Sporting News, January 28, 1959, 6.

22 Peary, 456.

23 Peary, 495.

24 Duren, 135.

25 Peary, 498.

26 The Sporting News, September 24, 1958, 5.

27 Duren, 140.

28 Duren, 145.

29 Duren, 146.

30 ibid.

31 Duren, 151.

32 Duren, 152.

33 Peary, 605.

34 Duren, 159.

35 Duren, 160.

36 ibid.

37 Richard Goldstein, “Ryne Duren, Yankees Reliever Who Made Batters Nervous, Dies at 81,” New York Times, January 7, 2011.

Full Name

Rinold George Duren

Born

February 22, 1929 at Cazenovia, WI (USA)

Died

January 6, 2011 at Lake Wales, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.