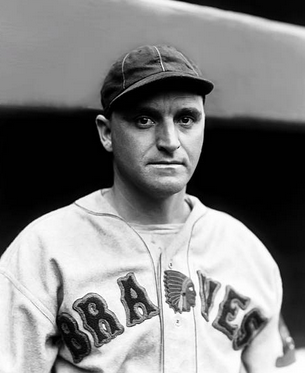

Socks Seibold

Harry “Socks” Seibold had a rather modest pitching career, compiling a record of 48 wins and 85 losses in 191 games over eight major league seasons. He was given the nickname “Socks” by his first manager, Connie Mack, who earlier had managed Philadelphia Athletics outfielder Ralph “Socks” Seybold. What was unusual about Harry Seibold’s career was that he had a nine-year gap between his first stint with the Athletics, which ended in 1919, and his return to the majors with the Boston Braves, in 1929. One of the more interesting aspects of Seibold’s career was his whereabouts between 1920 and 1928 and the circumstances that led to his return to the major leagues in 1929.

Harry “Socks” Seibold had a rather modest pitching career, compiling a record of 48 wins and 85 losses in 191 games over eight major league seasons. He was given the nickname “Socks” by his first manager, Connie Mack, who earlier had managed Philadelphia Athletics outfielder Ralph “Socks” Seybold. What was unusual about Harry Seibold’s career was that he had a nine-year gap between his first stint with the Athletics, which ended in 1919, and his return to the majors with the Boston Braves, in 1929. One of the more interesting aspects of Seibold’s career was his whereabouts between 1920 and 1928 and the circumstances that led to his return to the major leagues in 1929.

Harry M. Seibold was born May 31, 1896, in Philadelphia, the fourth of five sons born to Godfrey M. and Elizabeth (Evans).1 Harry’s mother was born in Philadelphia, but Godfrey was born in Germany, having emigrated in 1866. Little information has been found of Harry’s early childhood years, but his obituary printed in the October 9, 1965 issue of The Sporting News indicated he began playing semi-pro ball on sandlots in the Philadelphia and New Jersey area by the age of 15. By the time he was 18 years old, Harry caught the attention of Connie Mack, and was signed by the Athletics in 1914.

Mack sent Seibold to Cedar Rapids, Iowa of the Central Association, where he split time between the mound and shortstop. Seibold was called up by Philadelphia at the end of the 1915 season and played in ten games. He did not pitch, but appeared in seven games at shortstop and hit just .115 (3 for 26). In need of more seasoning, Mack sent Seibold to Wheeling, West Virginia in the Central League to start the 1916 season. Now exclusively a pitcher, Harry recorded a record of seventeen wins against just six losses, including a no-hitter. He was again recalled by the Athletics in September, and won his first major league game, shutting out the Browns in St. Louis on three hits in the first game of a September 14 doubleheader.

Between 1902 and 1914, the Philadelphia Athletics won six American League pennants and three world championships. These teams featured the famed $100,00 infield and a pitching staff that included Rube Waddell, Chief Bender and Eddie Plank. The Athletics were upset by the Miracle Braves in the 1914 World Series, and many of their star players who didn’t jump to the new Federal League were released, sold, or traded by Connie Mack. Harry Seibold had the misfortune of attempting to break in with the Athletics during a time in which they were the worst team in baseball, finishing in last place for seven consecutive seasons (1915-1922).

Seibold spent the entire 1917 season with the Athletics, posting a record of just four wins against sixteen losses. The frustration of pitching on such a poor team began to get to Harry. In one game, “when Connie Mack yanked him, Seibold stormed in and threw his glove against the back of the dugout. Mr. Mack said to him ‘Keep on going and don’t come back.’ Seibold didn’t start again for almost eight weeks.”2 Deserving or not, Seibold began to get the reputation as a temperamental ball player. Several years later the Reading Eagle (PA) wrote, “A great pitcher when ‘right’, but a very difficult individual for managers to handle – that’s been the story of Seibold’s long career in baseball. He was branded as being very temperamental in his first days under Connie Mack ….”3

Socks spent the 1918 season as Captain Harry Seibold with the United States Army’s 315th Regiment, a Philadelphia unit of the Liberty Division, stationed in Fort Meade, Maryland. His World War I draft registration card listed his occupation as “Ball Player” and his employer as “Connie Mack, Phila. Base Ball Club.” The same draft card indicated he had a wife and child4, but no other information has been found that indicates Harry was married at the time or had fathered a child. Seibold never saw action overseas during the war, and kept in shape playing for the post baseball team.

In February 1919, after his discharge from the Army, Seibold was signed again by Mack, and he made the Athletics’ opening day roster. On June 25, Mack called on Socks for mop-up relief duty in a 9-0 shellacking by the Yankees. Shortly thereafter, Seibold abruptly quit the team, “because I couldn’t stand to be on that kind of club any longer.”5 This was to be Harry’s last appearance in the major leagues for nine years. After a brief cooling off period, Philadelphia management persuaded him to join the club’s top farm team, the Baltimore Orioles in the International League, where he finished the season.

Mack sold Seibold to the Seattle Rainiers of the Pacific Coast League, where he pitched in 1920. He then was passed along to the Oakland Oaks in 1921. But, there is conflicting information as to where Socks was playing in 1922 and 1923. One source reported that the Oaks sold Socks to Sioux City of the Western League, “where Socks had fair success for a season.” In 1923, he reportedly played at Des Moines, “during which time Socks flashed some of his best pitching form,” and was then recalled by the Oaks for the 1924 season.6 However, there is no record of anyone named Seibold playing with either the Des Moines Boosters or the Sioux City Packers of the Western League in 1922 or 1923.

There were some accounts indicating that arm trouble was the cause of Harry’s disappearance from organized baseball. Other reports said that Harry’s notoriously hot temper and frequent run-ins with his managers and team officials likely also contributed toward his suspensions. Often, after being traded or sold to an organization he didn’t want to play for, he refused the new assignment and promptly quit. However, the best explanation for Seibold’s absence comes from an interview with Harry later in life in which he was quoted as saying “I pitched independent ball because I made more money out of it than either the majors or minors, and I enjoyed it too.”7

In 1922, Socks Seibold was actually playing semi-pro ball back in his hometown of Philadelphia. Seibold decided to drop out of organized ball and that “he was ordered to report to Sioux City … but would rather play in Philadelphia.”8 But, before the season began, he was reprimanded and fined $25 by the Philadelphia Baseball Association for having signed contracts with two different clubs. He was awarded to a club called South Phillies in the Penn-New Jersey League because he had signed that contract (on February 12) before he had signed with a rival team, Nativity Catholic Club (on March 30). That season, he also pitched for a team called the Philadelphia Shop in the Pennsylvania Railroad League. The next season, 1923, Socks appeared in box scores for a team called Northampton in the independent Lehigh Valley League in Philadelphia.

In 1923, there came the first of two occasions in which Socks was confused with another Harry Seibold. A player with the surname Seibold played for the Carrington-New Rockford Twins in the Class D, North Dakota League that year. Further detail in the local newspaper, the Foster County Independent, revealed his first name was Harry. David Trombley assumed this to be Harry “Socks” Seibold, as he wrote “Harry “Socks” Seibold … apparently played for Valley City in 1923 as a pitcher and outfielder (.246, pitching record not known).”9 However, this was not Socks Seibold: there were two Harry Seibolds playing baseball in 1923. Nothing more is known of the one playing in North Dakota other than this one unremarkable season.

Socks Seibold remained on the Oakland Oaks reserve list and returned to the team for the 1924 season. The Oakland Tribune commented that he “made a great record in independent ball around Philadelphia the past year.”10 Socks pitched in just twelve games for the Oaks before jumping the club in mid-June amid the management’s efforts to close a deal to send him to the Nashville club in the Southern Association. According to the Tribune, he had “faded away to parts unknown.” Needless to say, Socks did not leave Oakland on good terms. In August, the Tribune wrote that Harry Seibold would be remembered as ”stepping to the mound occasionally to help the enemy increase their batting averages” and later that “[he] proved to be a poor experiment for the local club.”

For his refusal to report to Nashville, Socks was suspended from Organized Baseball.11 Harry’s version of the events was that he did not want to play in the Western League and asked the Oakland club to put him on the voluntary retirement list.12 He returned home to the independent and semi-pro leagues on the east coast, and by July 1924 had hooked on with Chester, Pennsylvania in the Penn-New Jersey League. In addition to its league schedule, the Chester club faced two of the more prominent black teams in the area. On July 21, Seibold pitched against the Baltimore Black Sox and on September 11, he faced the famed Hilldale club.

Seibold pitched for Northampton in the Lehigh Valley League again in 1926, and is assumed to have pitched for them in 1925 as well. An October 8, 1928, story from the Reading Eagle stated that Socks was married to Elise Anna Stettler of Northampton and that he had “met his bride when he was playing with the Northampton ball club three years ago.” In 1927, he was employed by the Pennsylvania Railroad team of Philadelphia.

After a three-year absence from organized ball, Socks was reinstated and signed by the Reading, Pennsylvania Keystones of the International League for the 1928 season. Described as “staging a sensational comeback in organized ball this year”13, Socks won twenty-two games that summer and was considered one of the best pitchers in the International League. Despite being the team’s star pitcher, Socks was still a headache for his managers. At one point he demanded more money and “quit cold,” although manger Hinchman convinced him to rejoin the team a few days later. Later in the season he “pulled the same stunt again.”14 However, in an interview later in life, Socks said, “Reading was the best place I ever played. I’ll never forget it.”15 Nonetheless, after his one and only season with the Keystones, Hinchman sold Socks to the Chicago Cubs organization, which in turn traded him, four other players, and $200,000 in cash to the Boston Braves for Hall-of-Famer Rogers Hornsby.16

Harry returned to the major leagues and pitched for the Boston Braves, another second division team, for five seasons (1929-1933). Seibold’s reputation preceded him to Boston. As early as May of 1929, one source reported Harry had “quit in a huff after a salary dispute that has been brewing ever since Florida spring training days.”17 Another report indicated Harry was suspended by his manager, Judge Fuchs, “and unless he [Seibold] changes his attitude, is likely to remain suspended indefinitely.”18

Seibold had the added misfortune of attempting his comeback during an era when offense dominated major league baseball. Nonetheless, under new Braves manager, Bill McKechnie, Harry had his best season in 1930, going 15-16 in 251 innings. Arm injuries, a bout of appendicitis, and advancing age limited Harry’s effectiveness during the rest of his time with Boston, and in June of 1933 he was sold to the Albany, New York Lawmakers in the International League, his last appearance in organized baseball.

The second time that Harry “Socks” Seibold was confused with another Harry Seibold was in an obituary printed in Philadelphia Inquirer, in 1960, for a Harry C. Seibold. This Harry Seibold was also a native of Philadelphia, about the same age as Socks, and the obituary detailed the real Socks Seibold’s pitching record. Part of the reason for the confusion was that Harry C. Seibold also had connections to baseball, as at one time he was the owner of the Richmond, Virginia franchise in the International League. Socks contacted the Inquirer to inform them he was alive and well.19

After his playing career ended, Socks scouted for the Phillies in 1947 and the Giants in 1948.20 Later in 1948 he managed the Seaford, Delaware team in the Eastern Shore League, and by 1951 was out of baseball and working as a plumber in Philadelphia. He died September 21, 1965 at the age of 69 and is interred, alongside his wife, Elsie, who preceded him in death, at the Beverly National Cemetery in Beverly, New Jersey.

Notes

1 Ancestry.com

2 Norman Macht, Connie Mack: The Turbulent and Triumphant Years, 1915-1931, University of Nebraska Press, 2012

3 Reading (PA) Eagle, April 11, 1934

4 Ancestry.com

5 The Sporting News, October 9, 1965

6 Reading (PA) Eagle, June 8, 1930

7 Reading (PA) Eagle, January 10, 1960

8 Philadelphia Evening Public Ledger , February 1, 1922

10 Oakland Tribune, January 11, 1924

11 Boston Globe, May 18, 1929

12 Reading (PA) Eagle, March 9, 1928

13 Reading (PA) Eagle, May 28, 1928

14 Reading (PA) Eagle, April 1, 1934

15 Reading (PA) Eagle, January 10, 1960

16 Baseball-Reference.com

17 Rochester Evening Journal and Post Express, May 20, 1929

18 Boston Daily Globe, May 18, 1929

19 Reading (PA) Eagle, January 10, 1960

20 Hartford Courant, July 27, 1947

Full Name

Harry Seibold

Born

May 31, 1896 at Philadelphia, PA (USA)

Died

September 21, 1965 at Philadelphia, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.